Author: UC Berkeley Library

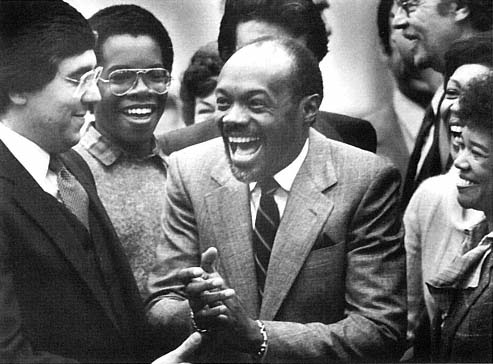

Willie Brown Oral Histories, UC Berkeley Oral History Center

“If you’ve ever thought to yourself, ‘What the hell was Willie thinking?’ … well, now you have the chance to hear for yourself!” — Mayor Willie Brown on his oral history

About the Willie Brown Oral Histories

Willie Brown was the 41st Mayor San Francisco, serving two terms between 1996 and 2004. Prior to that, Brown represented San Francisco in the California State Assembly for thirty years, serving as that body’s Speaker for a record fifteen years. During his four-decade political career, Brown was admired and despised, respected and feared by politicos statewide. His passion for politics and exuberant style of leadership attracted the attention of leaders and influencers nationwide.

Together, two oral history interviews from the UC Berkeley Oral History Center form a remarkable life story that began in the segregated town of Mineola, Texas, in 1934, and run through four decades in politics, law, and policy up to 2016, on the verge of that surprising presidential election. Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Willie Brown: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004 (2020)

Willie L. Brown, Jr.: First Among Equals: California Legislator Leadership 1964–1992 (1999)

Commentary by Interviewer Martin Meeker

Interviewer Martin Meeker comments on Brown’s importance to San Francisco and California politics, the significance of the oral history as a draft of the city’s history at the turn of the millennium, and what it was like to interview the legendary mayor. “At times deeply thoughtful and soft-spoken while at other times exuberant and laughing boisterously, Brown brought all his passion, intelligence, and personality to bear on the telling of this story.” Martin Meeker Commentary

Video

“His Williness” at Beach Blanket Babylon

San Francisco Chronicle political cartoonist Phil Frank repeatedly lampooned Mayor Brown, drawing him as a king; Willie Brown played the caricature in Beach Blanket Babylon, San Francisco’s iconic musical revue. Hear Willie Brown talk about handling criticism and the importance of laughter. “I enjoy any form of humor, whether it’s about me, against me, or with me. I really love to laugh.” (p. 145–146)

Photo: “His Williness” as drawn by cartoonist Paul Frank, from the Phil Frank Archive of Comic Strips, The Bancroft Library (Banc pic 2012.032).

Foreword to the Oral History By Mike Roos

Find out why Mike Roos, Member of California State Assembly, 1977–1991, found Willie Brown to be passionate, spellbinding, authentic, and brilliant — and “the most effective state leader in the later part of the twentieth century in the most influential state in the United States.” Mike Roos on Willie Brown

Oral History Transcripts

Willie Brown: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004

The 10-hour history begins with the remarkable tale of how Democrat stalwart Brown managed to get re-elected Assembly Speaker in 1995, even after Republicans won a majority in the state Assembly. Facing the prospect of terming out of office, Brown then set his sights on running for San Francisco mayor. The new oral history then delves into his successful campaigns for mayor in 1995 and 1999; Brown’s first term agenda, including tackling economic development, homelessness, housing, and the development of an entire new neighborhood, Mission Bay, now home to the University of California San Francisco, the San Francisco Giants and the Golden State Warriors; and his appointments to the Board of Supervisors. The history moves on to his second term agenda, including replacing the Transbay Terminal; the city’s housing crisis; so-called “Progressives” in San Francisco politics; and his own reflections on his image and legacy.

The Willie Brown: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004 oral history was sponsored by the University of California, Office of the President, under the leadership of then-President Janet Napolitano.

Willie L. Brown, Jr.: First Among Equals: California Legislator Leadership 1964–1992

Spanning nearly fourteen hours, Willie Brown’s first interview with the Oral History Center documents the events of his life preceding his election as mayor of San Francisco. Brown begins with his experience growing up in the segregated town of Mineola, Texas, where he was born in 1934. He then describes what is perhaps the major physical turning point in his life: the move from Texas to San Francisco, where he would eventually rise to unprecedented political and cultural influence. His story in the city begins in 1951 with his years at San Francisco State University, where he first became involved with Democratic politics. He also describes his time at UC Hastings School of Law and his resulting law practice of the late 1950s and early 1960s, during which he continued his involvement in politics. The oral history goes on to explore his journey to the California State Assembly and expands on his career and contributions as a member of the legislative body. He then describes how he became speaker of the assembly and the issues he faced in the position, including government organization, revenue and taxation, African American equity, and challenges within the Democratic Party. Finally, he recounts his experience as chairman of Jesse Jackson’s 1988 campaign, the major issues facing California in the early 1990s, including welfare, workers’ compensation, and health care in California during the early 1990s, and the dangers of term limits.

Notable Quotes

Written excerpts from the Willie Brown oral history transcript on topics and people including:

Topics

- Absentee ballots as election strategy

- Identity politics

- Progressives in San Francisco politics

- Homelessness; affordable housing

- Economic redevelopment; Mission Bay

- Education budgets and party politics

- The importance of diversity in appointments

- The power of Democrats in the State Legislature

- Term limits

- Building the central subway system

- Incorporating lessons from past experience

Individuals

- The public’s perception of “Willie Brown”

- Early impressions of Bill Clinton

- Maxine Waters’ early recognition of Bill Clinton

- Response to Hillary Clinton’s healthcare plan

- Early impressions of Gavin Newsom

- The political power of Nancy Pelosi

How to Request Audio

To request audio from anywhere in the transcript, please send an email to BerkeleyOHC@berkeley.edu. Be sure to include beginning and ending time stamps.

Assembly Member Mike Roos on Willie Brown

It is my honor to say, “Meet Willie Brown: a timeless leader.”

Editor’s note: We asked Mike Roos, Member of the California State Assembly from 1977–1991, to write the Foreword to the Willie Brown oral history, which we are pleased to share with you below. Read the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s oral history, Willie Brown: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004. See more resources, including the oral history, commentary, videos, articles, notable quotes, and more.

by Mike Roos, Member of California State Assembly, 1977–1991

I first “met” Willie Brown in 1972. I was working in Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty office in Los Angeles.

Politics and public service were the constant objects of my attention. Watching the Democratic convention on television, I was suddenly riveted by the passionate and perfectly elocuted speech persuasively urging the seating of his California delegates. At close, the hall erupted in sustained and then thunderous applause. I never forgot his name and yearned our paths would cross one day. And they did.

In 1975, we met again. I was in the gallery of the California Assembly chambers when what proved to be the landmark Consenting Adults Bill was debated. Not much to my surprise, but certainly to my delight, the author, the same Willie Brown of 1972, rose to present the legislation. Without notes, he proceeded to spellbind the membership (and gallery), brilliantly arguing the law should focus on the consent of the adult for the sexual act, not the act itself. He won the day and California scored another progressive first with Governor Jerry Brown’s signature.

I personally met Willie Brown on the floor of the California State Assembly in June of 1977—as a colleague. I had just won a special election to fill a seat vacated by an incumbent to assume a federal appointment. I had now realized an ambition unthinkable as recently as a year earlier.

Now, here I was observing and participating in everything around me, but always with a keen eye on the work and moment of Willie Brown.

In those days, he was involved, yet detached from daily legislative life. He had lost a contentious contest for Speaker. The winner, Leo McCarthy, had publicly exiled him. Yet, the adage that the institution needs and requires its top talent led McCarthy to appoint him Chairman of the Revenue and Taxation Committee. Willie accepted with the caveat that he would faithfully chair his committee, attend floor sessions, but otherwise be in San Francisco.

Who knows, had a hostile contest for the speakership not erupted in 1979 between McCarthy’s majority Leader and McCarthy himself, Willie’s legend may have been written in the annals of famous trial lawyers: Think Johnny Cochran.

Nineteen seventy-five became a lesson in combative leadership for me and virtually every member of the Democratic caucus who had chosen to stand with McCarthy. Without formal title, Willie fluently became the instructor.

It was a revelation to watch him stealthily come into a caucus, move unassumingly to the back of the room, listen as the conversation moved gloomily to capitulation, and then, Willie, upon recognition, asking had anyone read the rules of the Assembly. Stunned looks transformed into cautious optimism as Willie, in measured tones, explained that a speaker could only be removed by forty-one votes. Everyone’s assumption had been that a majority vote by the Democratic caucus (which the majority leader had) would determine the outcome.

I devote time to this watershed event as it defines the moment for me and others what it meant to keep your head, while others were losing theirs.

This story ends well as McCarthy stepped aside after the November elections. Maxine Waters, Elihu Harris, and I persuaded Willie he could assume the mantle of the Speakership and prevail, which he did in a matter of thirty days prior to the scheduled vote.

And that brings us to a remarkable run as Speaker of the California Legislature. It is a remarkable record in which he addresses the AIDS epidemic, South African sanctions to confront and destroy apartheid, the first assault weapons ban, requirements to wear seatbelts, and on and on. Progressive legislation becoming models for the rest of the states.

Eventually, after holding the Speakership longer than anyone else in California history, he then left his beloved legislature to become an equally effective Mayor of San Francisco. It is all spellbinding in what follows.

My job here is to make a quick and brief introduction to the man.

What I really want to accomplish is to call out how special a public leader he was.

Someone once said in response to the question of how you define leadership, “You know it when you don’t have it.” I posit there is something primal in how we gravitate to people who we ultimately rely upon to lead.

It entails the rhythm of speech, the quality of laughter, the authenticity of personal caring and engagement, unpracticed intelligence, and kinetic energy. Willie Brown was blessed with, yet constantly developed these attributes through meticulous effort to become the most effective state leader in the later part of the twentieth century in the most influential state in the United States.

It is too easy and, again, fairly human to forget those of previous generations, but somehow you have been drawn to listen to him for some purpose.

I urge you to really get to know him through these masterful interviews. You are in for a unique ride with the most accomplished leader I have ever witnessed.

It is my honor to say, “Meet Willie Brown: a timeless leader.”

Notable Quotes from the Willie Brown Oral History: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004

“I encourage you to read the entire oral history, which represents nothing less than Willie Brown writing perhaps the first consolidated draft of the critical history of San Francisco at the turn of the millennium.” — Martin Meeker, Interviewer and Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

Willie Brown was the 41st Mayor San Francisco, serving two terms between 1996 and 2004. Prior to that, Brown represented San Francisco in the California State Assembly for thirty years, serving as that body’s Speaker for a record fifteen years. During his four-decade political career, Brown was admired and despised, respected and feared by politicos statewide. His passion for politics and exuberant style of leadership attracted the attention of leaders and influencers nationwide.

Together, two oral history interviews from the UC Berkeley Oral History Center form a remarkable life story that began in the segregated town of Mineola, Texas, in 1934, and run through four decades in politics, law, and policy up to 2016: Willie Brown: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004 (2020) and Willie L. Brown, Jr.: First Among Equals: California Legislator Leadership 1964–1992 (1999).

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

How to request audio

To request audio from anywhere in the transcript, please send an email to the director of the Oral History Center, Martin Meeker (mmeeker@library.berkeley.edu). Be sure to include beginning and ending time stamps.

Excerpts

Below are excerpts from the new oral history, presented in the order in which they appear in the interview, with time stamps for the audio and page numbers for the transcript. Topics and people mentioned include:

Topics

- Absentee ballots as election strategy

- Identity politics

- Progressives in San Francisco politics

- Homelessness, affordable housing

- Economic redevelopment, Mission Bay

- Education budgets and party politics

- The importance of diversity in appointments

- The power of Democrats in the State Legislature

- Term limits

- Building the central subway system

- Incorporating lessons from past experience

Individuals

- The public’s perception of “Willie Brown”

- Early impressions of Bill Clinton

- The public’s response to Hillary Clinton’s healthcare plan

- Gavin Newsom

- Nancy Pelosi

On education budgets and party politics

Brown provides an example of an effort he made to sway public opinion towards the Democratic Party. Pete Wilson, then governor and Republican, cut education funds for kindergarten, and Brown knew that would upset the public. 01-00:08:29; p. 4

And when he [Pete Wilson] announced that all we’d have to do is no longer have kindergarten we were delighted because we knew that all those mothers that had been with those kids for four or five years, not able to go to lunch, not able to get her hair done, she’d been waiting to get rid of that kid. And we knew, Republicans and Democrats, we knew that he had made a mistake. We went to the teachers and made sure that with their resources they put every shot of him making that comment on every television station, whether it was in Chico or Chino. We made sure that every television station and every radio station, every newspaper, had it. Every editorial board. And it was not long before the tide turned when he said he was going to abolish kindergarten. We started talking about saving kindergarten, not saving the teachers’ salaries. Start saving kindergarten. And so we ended up literally exploiting the hell out of that mistake by him in the July/August saga just leading up to the November election.

On Maxine Waters’ early recognition of Bill Clinton

Brown recalls that Maxine Waters supported Bill Clinton early on. 01-00:17:11; p. 5–6

Maxine is probably the best bellwether of quality principled politicians. She seldom, if ever, tolerates anything less than the ultimate quality on the decision. And I think she saw Bill Clinton in that vein. She may have had a closer look at Bill Clinton because she comes from that area. She comes from St. Louis, Missouri. My guess is that her history and her relationships down there had given her a better perspective on Clinton than most of us ever had on Clinton. We had paid him virtually no attention at all. She had been riveted on Clinton from day one, though.

On the power of Democrats in the State Legislature

Brown talks about Democrats controlling the California State Legislature. 01-00:19:44; p. 6

Democratic caucus members in both the senate and the house, constituted the real Democratic Party in California. We were it. We were the power brokers. And that situation remained for a long time, by the way.

On women candidates

Brown explains the practical reasoning behind Democratic support of women candidates. 01-00:19:44; p. 6–7

We did think, however, the women’s candidacy in the year of the women had been helpful because we had been for some time, on the leadership edge, trying to empower women. As a caucus we had dedicated ourselves to equal funding for women candidates. And it was practical. Women were seldom, if ever, subject to the attacks that guys were subject to in a campaign. You couldn’t demonize a woman as you can demonize guys in campaigns. Women were never suspected as being players or drunk drivers or even dishonest. And on a practical basis in the early eighties we came to the conclusion that if we could find women candidates, we can beat Republicans in Republican districts. And that’s what we had kind of set out to do. And in the process, obviously, it became clear that we could win Democratic seats easier with a woman than we could with a man. So we literally became a partner and we treated the women’s movement as a partnership, whether it was Emily’s List or any of the others.

On the public’s response to Hillary Clinton’s healthcare plan

Brown talks about Bill Clinton tapping Hillary Clinton to fix the healthcare system. 01-00:29:20; p. 8–9

And so the first season of [Bill Clinton’s] presidency was marred by the absence of marketability of great ideas. And symbolically with the healthcare measure, which was not new. People have been trying to do something with health for sixty or seventy years. Republicans and Democrats, and they had all failed. And he handed it off to Hillary. Maybe she took it without being asked. And she became, and still bears, the title among some of the detractors, of some kind of an evil person or an evil individual. And they ran away from her.

On term limits

Brown lays out his thoughts on term limits. 01-00:53:33; p. 15

I believe that you ought to abolish term limits, period, and I think that ought to be the quest and you ought to line up the League of Women Voters, you ought to line up everybody and keep assaulting…that concept. Because there are some people that shouldn’t get one term and then there are others that ought to stay as long as the voters will have them because, after all, that’s what it is. It’s a voter’s choice. And when you limit the voter’s choice you take out really talented people.

On the importance of political contacts

Brown discusses the many political contacts he had, including Nancy Pelosi, that made it possible for him to achieve his goals for the city of San Francisco. 02-00:09:39; p. 24– 25

The things that pushed me probably more than anything else was the prospect of being able to solve the problems and fashion a solution to the problems in San Francisco and that the political climate was ripe to so do that. . . . With Nancy Pelosi clearly rising in power in the Congress and with the contact, relationships there. . . . And with my vast array of relationships with people who would continue to be in Sacramento, those who had migrated to the Congress as a result of term limits.

On economic redevelopment

Brown discusses the relationship between the redevelopment commission and the planning commission in city projects. 04-00:01:38; p. 59

A redevelopment area is a geographical space within a city or county in which rules that are fashioned both at the state level and the federal level are applicable as it relates to land use rather than the local controls. Period. Whether it’s height, whether it’s what can be there — because the opportunity and the concept of redevelopment was to take an area that was economically deprived, under-producing, or a slum, and rehab it. And you can’t always be burdened with whatever the obligations are under the planning code as it relates to the area that isn’t subject to slums, that isn’t subject to any of the kinds of things that go there. Redevelopment also allows for the acquisition of personal property belonging to someone without the great challenges you face when you do it in an isolated fashion under the concept of what people can usually do to acquire property in the hands of others. And so the redevelopment agency heads and directors of planning are usually archenemies. They really don’t particularly like each other. The role that the mayor in that situation necessarily has to play is to be the referee between the respective parties and in fact insist upon adherence to their defined statutory roles. And in my administration that’s essentially what we did.

On developing Mission Bay in the eighties

Brown discusses the beginnings of developing Mission Bay, which had gone on to transform San Francisco and become his “signal achievement” as mayor. 04-00:07:36; p. 80

Well, first and foremost, the prospect of developing [Mission Bay] literally required finding somebody willing to put money in for that purpose. And a Canadian company won the rights to own and operate and develop on that particular piece of turf. And they hired their own people to do the work there. Frankly, in the eighties the city didn’t pay a lot of attention to what was going on there and nobody was in an urgent mood to push that development.

On San Francisco’s identity politics

Brown attributes an elevated sensitivity on race in politics to Phil Burton. 05-00:10:25; p. 84-85

You would have to attribute much of that elevated sensitivity on race to a fellow named Phil Burton. He was a man who ran for state assembly and lost to a dead man and he won the next time out and he was the first, I think, to really energize labor to do something other than just support labor persons for office. And it was what is now the SEIU [Service Employees International Union]. It was an organization that had its office over on Golden Gate Avenue and I forget exactly the name. But nevertheless, it was something that Phil Burton marshaled. Phil Burton also saw the potential for Asian voters, in particular Chinese, and he focused on trying to get some symbols of that. He saw the absolute need with his friendship with a fellow named Carlton Goodlett, who owned the black newspaper at the time. And they were both basically left-wingers. They were persons who looked with some favor on the candidacy of Vincent Hallinan for the presidency back in 1952. Growing out of that, Phil Burton began to think about the clear potential for assembling a sufficient number of people for voting purposes from various constituencies. And he became part of the NAACP. As I said, he was a part of the labor movement. His headquarters was actually in the labor temple on 240 Golden Gate Avenue for a guy named George Hardy, who ran that labor union at that time. And Phil was about that effort. Phil also was about making sure that the real political union, which was Harry Bridges operation, the longshore and warehouse, that they were part of that effort. And so he really is the founder, in my opinion, for San Francisco of the elevated sensitivity to potential for broad representation among people of color, in particular.

On returning to community after success

When Brown first arrived in California, he worked low-wage jobs to finance his education, including working as a janitor at the Jones Methodist Church. Later as a lawyer, he helped the organization acquire legal rights to build affordable housing for community members. 05-00:19:44; p. 88

I worked as a janitor in that church. I lived in that church for a brief period of time while I was still in school and the Boswells were always great friends. I worked as a youth coordinator, MYF it was called, Methodist Youth Fellowship, and I was the director of the Methodist Youth Fellowship at Jones Methodist Church. When I became a lawyer, I became the lawyer that incorporated the Jones Memorial Homes, Inc., the nonprofit organization that built the senior housing on the church land and ultimately affordable housing across the street from the church from land acquired along Post and Fillmore.

On Gavin Newsom

Brown recounts his impressions of Gavin Newsom, who had been appointed to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors by Brown during his first term. 05-00:36:14; p. 92–93

Gavin Newsom campaigned with me. Was dedicated. He and his roommate, was Billy Getty, and they were the young white entrepreneurs who really wanted me to be the mayor. And they were the owners of bars, restaurants, liquor stores, and other kinds of things. And I met Gavin because I knew his father. His father had been a candidate for state office whom I had supported….And I already knew of young Newsom because during the course of my campaigning for mayor he created something called the Bar Crawls and he would take me at nighttime, whether it was on Geary, among the bars on Geary, he’d go in and he would buy everybody in there a round and introduce them to his candidate for mayor, Willie Brown. And he did the same thing down in Cow Hollow, on Chestnut Street. And so he was frankly invaluable. I had appointed him already to the chair of what essentially was the traffic commission and I wanted to do something about cleaning up the taxicab industry. I called a taxi summit. Only person that spent the same number of hours at that summit as I did was Gavin Newsom. So I knew that he was a real student of public activities.

On homelessness

Brown discusses how his stance on homelessness brought backlash. 05-00:58:45; p. 98–99

We were identified as being indifferent to the needs of the homeless people because I had said, “Homeless problem is impossible to solve.” And the homeless advocates went crazy. They were certain that I was anti-homeless by virtue of saying that. And nothing has proven to be more accurate, by the way, than that comment for all over the nation because you don’t have any way to force people to take medication. You don’t have any way to force people off the streets. You don’t have any way to force people to take counseling and treatment. And you don’t really acknowledge how multiply challenged many of the people who are out there on the streets are. I canceled the homeless summit. I was going to do a homeless summit and I concluded that it would be a waste of time and I canceled the homeless summit. I did so many things of that nature and I generated such hostility that you would not believe.

On building the central subway system

Brown recounts the efforts he made to approve the construction of the central subway system during his time as mayor. 06-00:02:33; p. 106

It takes a lot of money and a lot of commitment to put together a subway but we, in fact, actually did that through the process of the administration in the second time around and the efforts that were made to achieve that goal. Central subway process, the construction, did not start until in the first year or so of my exit, maybe even the second year of my exit from the mayor’s office but the foundation had been completed by then. We had great luck in that Nancy Pelosi was growing with great power in the Congress, obviously eventually becoming the speaker within the decade, the first decade of the twenty-first century. Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer were both clearly on the ascendency power wise. A combination of those three things, plus my long-term friendship with people like then Governor Schwarzenegger, lent itself appropriately to the ultimate implementation of that long twenty-plus year subway, central subway concept and central subway way.

On incorporating lessons from past experience to mayorship

Brown believes that his extensive experience in the legislature helped him build effective coalitions. 06-00:13:56; p. 108–109

Well, first and foremost, in my capacity as mayor of San Francisco, all of the skills and experience I had at working with seventy-nine other members of the legislature in the assembly, plus forty members of the state senate, has always led me to position whatever I was attempting to do in a way in which it’s of equal interest to people I’m trying to gain support from. So as mayor, with regularity, my appointing powers, I shared them with other elected officials, and in particular with Nancy Pelosi and Dianne Feinstein. I would not hesitate on any opportunity for any kind of involvement by people who were not elected officials. I’d seek advice and recommendations from elected family, the elected family.

On “progressives” in San Francisco

Brown on the approach of San Francisco progressives. 06-00:49:09; p. 116

They [the progressives] were appealing to the group of people who arrived yesterday but wanted to keep the city as it was before they arrived. And they really had made great arguments and generated enthusiasm for that concept. They were never able to carry out any of their objections. I, through the years of my mayorship, continuously made progress toward what we see today.

118 (More on progressives)

The interesting thing about the challenge to me [from the progressives] was [that it was] not an alternative method of productivity. It was strictly an effort to try to have everything stop and then figure out what to do after you stopped everything. Build nothing. Produce nothing. Do nothing. And then we’ll plan. So it wasn’t as if there was an alternative to the central subway. It wasn’t as if there was an alternative to the T-line going out to the Bayview. It wasn’t like that was an alternative to what we should do with Treasure Island if we get it from the feds. It wasn’t like that was an alternative to what ought to happen to Presidio if we get it from the feds. No, it was, “Let’s stop everything and let’s just see what we’ll do after we stop everything.”

On affordable housing in Mission Bay

Brown discusses how the 2001 recession brought on economic challenges that led to a focus on affordable housing. 06-01:11:17; p. 124

What we didn’t delay though, fortunately, was whatever affordable housing we had going. Because we had with the Mission Bay operation, if you’re going to do Mission Bay you’ve got to build the affordable housing first. And we had done that in other locations, but in particular in Mission Bay. So the first thing built in Mission Bay, literally the first thing built in Mission Bay on the residential housing side were affordables. And the interesting thing about it is the way in which we did the envisioning of the project. You can’t tell what’s an affordable housing unit in Mission Bay and what isn’t. They all look the same. And that was part of what we kind of learned under the process of the Hope Six projects that we did in and around the city, whether in Bernal or wherever. All of that literally continued because the government subsidized and the government prompted structures continued and they were primarily—and it’s too bad. I really couldn’t have envisioned, because I should have jumped on the chance to build five times as many affordables and we wouldn’t have the crisis we currently have in some cases or we’d be able to deal better with the crisis. Nobody was building anything for commercial occupancy purposes because there were no prospective tenants to occupy on the commercial side. Nobody wanted it.

On “working-class housing”

Brown addresses the housing crisis among the working class in San Francisco. 06-01:21:18; p. 126

We called it working-class housing. We wanted teachers. We wanted cops. We wanted Muni drivers, we wanted hospital workers. All of those people were beyond the affordable housing group. We had literally taken care of, allegedly, the dirt-poor. We had taken care of that crowd. So we started to try to figure out how can we now allow the working class—workforce housing is how we defined it and we turned our attention to workforce housing. We never did solve the problem. We never did, I don’t think, effectively address the issue and it’s still out there as an item that clearly needs to be addressed. Period. And as they discuss at the board today, the whole question of affordable housing, they ought to switch that term because the developers overnight would adjust themselves for the opportunity to develop if they had a clear understanding that on a step-by-step basis there would be the kind of affordability questions answered based upon what people actually earn. Because if you’re going to build housing that you primarily want public safety workers, fire and police to occupy, you know what they’re going to be making, so you the developer can actually structure your financing of your project on the basis that this is who’s going to occupy your project. You’re not into that nebulous category of 12 percent, 20 percent and you don’t know who they are, you don’t know whether or not when you think in terms of the operational cost on a monthly basis. The operational cost on a monthly basis could exceed the mortgage. Well, all those kinds of things you need to build into the so-called workforce housing cost. And I bet you developers would jump at the chance.

On the importance of diversity in appointments

As mayor of San Francisco, Brown made sure that the diversity of the city was reflected in his appointments. 07-00:52:47; p. 141–142

First you should know that my inaugural address at the Yerba Buena Gardens included the announcement that Fred Lau, an Asian, first would be police chief, and that Bob Demmons, who had been the plaintiff against the fire department to integrate it, would be the fire chief. Right out of the box that was a message that had not been heard before. And that was followed very quickly with the chairmanships of those two committees being controlled by racial minorities, all women, and that reflected itself throughout the chain.

On the public’s perception of Willie Brown

Brown feels privileged as a high-profile politician whose community knows much about his track record. 07-01:09:27; p. 146

And the perception of who Willie Brown really was is what sustained me because you could not define me without there being competition for the definition. Period. If I’d been unknown, if I’d been kind of a mystery, I’d kind of been anonymous, you could get away with what Trump does to people. Lying Ted or Little Marco or Crooked Hillary. Well, you couldn’t do that with Willie Brown. It just couldn’t stick. People knew too much about me. They had their own attitude and they would know whether or not the one you were trying to dump on me was applicable. 146

On Brown’s early impressions of Bill Clinton

Brown looks back on his interactions with Bill Clinton, before Clinton became governor of Arkansas. 01-00:05:53; page 3

Bill Clinton had arrived in California in the late eighties. He represented the Democratic Leadership Group, and that was the more moderate Democratic governors. And he had come out in a cheap shiny blue suit with a full head of hair. We had him appear at our caucus. We have caucuses every Tuesday and we had Bill Clinton come to our caucus. And he was a fun guy. He really was a fun guy. Not a good poker player, blackjack player, or any of the games that we were playing in the lounge. But he was fun and we got to know him on a personal basis rather than just in the governorship title.

On getting absentee votes before election day

Brown describes the process of banking absentee votes before election day, noting that it is more efficient today due to the electronic communication system. 07-01:21:03; p. 148–149

You simply start your solicitation of people whom you know will vote for you for sure but who in the past have been hesitant to be consistent in their actually casting a ballot. So you put a ten-person team together and every day of the week each member of that team will be required to produce a certain number of absentee ballot applications. Any time they don’t meet the standard you’re requiring you replace them with somebody else who will. So you set your goal of 25,000, let’s say, absentee ballots. If you have solicited the application, you have made sure it was filled out, you made sure it was sent in, chances are they voted for you. And that’s what we did. We started the process of early voting. We even went so far as to get an investigator for it. We had decided that in the public housing projects I’m going to get 80 percent of the vote only if they actually voted. So we had a separate operation for public housing and we did it two ways. We did it either absentee ballot or we did it through the management of the individual public housing units. Or we did it with A. Philip Randolph Institute every day driving people to city hall from the public housing projects, having them cast their vote early in the basement of city hall, then taking them for a hotdog after they finished and taking them back home or taking them back to where they were picked up from. And we did that religiously. That’s how you do it. You come up with a plan and a program.

Now you do it even more efficiently and effectively because you can use the electronic communication system. Period. We didn’t have the electronic communication system. My last time ever on the ballot was 1999. And we didn’t have that. It was not available to us. So we had to use the practical paper method and we did that. Now you can actually produce an absentee ballot application and get that done easier by way of the social media context and the person who masters that is going to be enormously benefitted by virtue of being able to do that. A fellow named Ace Smith, who runs Hillary’s operation just did that to Bernie Sanders. Bernie Sanders had no real access to absentee balloting, although he had great command of the social media. He didn’t translate it into an absentee ballot process. In some states they are now going written ballot. Oregon, I think, is 100 percent written ballot. I think we’ll eventually get close to that in California. But we were the pioneers when we didn’t have electronic means to assist us.

New Oral History: Willie Brown, Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004

by Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

Former San Francisco Mayor and State Assembly Speaker Willie Brown is a political force and personality known well beyond the provincial world of local politics. During his decade and a half leading the State Assembly, Brown was admired and despised, respected and feared by politicos statewide. His passion for politics and exuberant style of leadership attracted the attention of people nationwide. He appeared numerous times on Bill Maher’s and Chris Matthews’s television programs and is certainly one of the few politicians with a robust IMDb profile, listing appearances in films from the Godfather III to George of the Jungle.

It is in San Francisco, however, that he is best known and where he has exerted the most impact. In addition to representing the city in the state legislature from 1964 to 1995, he served two terms as the city’s mayor from 1996 to 2004. He has also been woven — or woven himself — deep into the fabric of the city, in many ways graduating into the roles once held by “Mr. San Francisco” Cyril Magnin and legendary “three dot” journalist Herb Caen. As the face of San Francisco, Brown not only appeared in several special productions of that only in The City production “Beach Blanket Babylon,” but “His Williness” became a recurring character in that long-running production. And Brown has become among the most widely read writers for the San Francisco Chronicle in his column that features insight into politics, unfettered opinion, and, of course, some good gossip.

This roughly ten-hour interview continues the story begun in the nearly fourteen-hour oral history conducted by the Oral History Center in 1991 and 1992. Together, these interviews form a remarkable life history that began in the same, segregated town of Mineola, Texas, in 1934 and runs through decades in politics, law, and policy up to 2016 on the verge of that surprising Presidential election. The earlier oral history, released in 1999, contains Brown’s memories of being raised in Texas, his journey to California as a young man, his education and early career as an attorney fighting for civil rights, his political alliance with Phil and John Burton, and his decades as an effective and determined legislator.

“Brown brought all his passion, intelligence, and personality to bear on the telling of this story.”

The interview released here begins with the remarkable tale of how Democrat stalwart Brown managed to be reelected Assembly Speaker in 1995 even after Republicans won a majority in the Assembly. Facing the prospect of terming out of office, Brown then set his sights on the office of San Francisco mayor.

Shortly after I first arrived at the Oral History Center in 2003 I had the opportunity to read the first Willie Brown oral history as part of a personal research project. It is always a remarkable experience to read a well-done oral history of a public figure — one thinks that they know such people well simply by their ubiquity, but a good interview should reveal something much more. I decided that the interviewer, Gabrielle Morris, had done a remarkable job and then-Speaker Brown not only showed up, he was deeply engaged, told a great story, and exhibited pride in the work that he had done. I resolved then and there that I wanted to be the interviewer for the second chapter in his life story — Mayor Brown — and I was thrilled to have gotten the chance in 2015 when then-UC President Janet Napolitano sponsored this oral history.

Mayor Brown and I met for seven sessions over the course of about a year and a half. Most of the interviews were recorded in the boardroom of the California Historical Society on Mission Street. Whether dressed in a suit and tie or something more casual, Brown always looked dapper and prepared to meet the world. In fact, more than once he was stopped coming and going by passersby who, a little starstruck, wanted to say hello or grab a quick selfie with the man. At times deeply thoughtful and soft-spoken while at other times exuberant and laughing boisterously, Brown brought all his passion, intelligence, and personality to bear on the telling of this story.

I encourage you to read the entire oral history, which represents nothing less than Willie Brown writing perhaps the first consolidated draft of the critical history of San Francisco at the turn of the millennium. But there are certainly some sections that were so intriguing — and raised so many further questions — that you’ll want to not skip those. When Brown took office in January 1996 (San Francisco holds mayoral elections in odd years), the technology boom was barely in the fledgling phase and rents, while going up, were still affordable to the many young people attracted to this unique city. Brown discusses the moves he made to make the city attractive to this new ‘clean’ industry and then the initial steps he took to accommodate the new residents streaming in. Brown admits that he didn’t foresee the extent to which the city would change, but what he did anticipate is remarkable.

The mayor’s ability of recall is notable, so the exchanges about politics and policy are substantive, but when he reflects about the character of his adopted home, the oral history becomes something perhaps even more interesting. Close to the end of the interview, I asked him about his appearance on stage for the 25th anniversary of that only in San Francisco musical revue Beach Blanket Babylon. Brown appeared as the character “His Williness,” a regal figure based on Phil Frank’s cartoon that tended to hector the more imperious aspects of the mayor’s reputation. Aside from a great telling of how this came to be, you’ll need to read the oral history to discover the intriguing thoughts the mayor had of it.

The oral history then delves into:

- His successful campaigns for mayor in 1995 and 1999 and his unfettered thoughts on his competitors, Mayor Frank Jordan and Supervisor Tom Ammiano;

- Brown’s first term agenda: economic development, homelessness, housing, Mission Bay development;

- His appointments to the Board of Supervisors, which included Gavin Newsom, then a political unknown, and Mark Leno, who went on to represent San Francisco in the State Assembly and State Senate;

- His second term agenda: Transbay Terminal, housing, and dealing with the possibilities and difficulties of the original “Dot Com Boom”;

- The emergence of a surprising group of political antagonists in the form of San Francisco “Progressives”, who tried to push the city ever further to the left;

- And his own reflections on his image and legacy.

I am thrilled to have had the opportunity to conduct this interview and am pleased to present it to you here.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Willie Brown: Mayor of San Francisco, 1996–2004

Willie L. Brown, Jr.: First Among Equals: California Legislator Leadership 1964–1992

Editor’s note: Find more resources on the Willie Brown oral histories, including commentary, videos, notable quotes, and more.

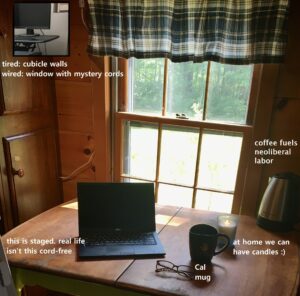

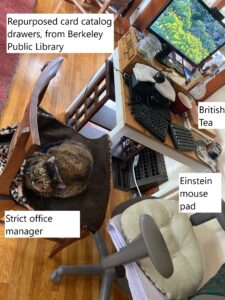

WFH edition (plus cats)

In the almost six months that we’ve been working at home we have tried to maintain a sense of community through meetings and retreats (via Zoom, of course), collaborative projects, and virtual coffee dates. However, beyond a few peeks on Zoom, we didn’t know what our colleagues’ work environments looked like, so we put out a call to our co-workers in the Social Sciences Division, asking them to share pictures of their home offices. We now present to you the range of ways we are continuing to stay connected to the Library and our work!

But first– a few words from colleague Natalia Estrada, who best sums up the challenge of working from home — even for those of us who were able to bring home our beloved dual monitors from our campus offices:

I live in a one bedroom apartment in a noisy part of town with a ton of construction. My spouse is also in academia, so we both are handling various Zoom meetings (sometimes at the same time!) and other large projects. You can imagine that working from home has been a challenge, bordering into impossible at times. The spouse and I have taken on many habits to try to make work-from-home in a small space work for us. We ended up rearranging our living room to create a better work station, using furniture we’ve acquired second hand (Urban Ore is a great place for this), plus taking certain needs into consideration. The work station, shared between the both of us, includes:

- a whiteboard used for teaching

- headphones, so I can block out distractions while I listen to a delightfully informative podcast (or the new Phoebe Bridgers album)

- two of our thickest cookbooks to use as laptop stands for presentations

- a desktop usually for processing large data sets, but also useful for touch ups before all those video meetings

- one of our many much needed mugs (this one comes from Valois in Chicago)

- a “work station” for our cat/office manager, so she can hang out while we work (she is a very good cat, but a bad office manager)

- artwork! Because artwork works great as a background (better than a laundry rack, at least for us). We like both the block print from Suzhou, China, and the concert poster from when Japanese metal band Boris played at Amoeba.

We’ve still faced various hurdles that make it hard for us to work at 100 percent, especially when one has the desk and the other has to Choose-Your-Own-Adventure a second work spot (the couch? the bed? the kitchen? the choice is yours!). But, hey, my cat digs all the attention she gets on Zoom!

The Fighting Spirit of Ida Louise Jackson

One of UC Berkeley’s first African American graduates and Oakland’s first black teacher

by Deborah Qu

In 1921, the members of the black sorority Alpha Kappa Alpha stood proudly together for a photo to be featured in the University of California’s yearbook, the Blue and Gold. Among them was Ida Louise Jackson, the founder of the Rho chapter of AKA, one of two black sororities established that year. They knew that the day was going to be memorable, but unfortunately it was unforgettable for the wrong reasons. Jackson had scrounged 45 dollars from her parents for the photograph. Yet, despite meeting all requirements, when the yearbook came out their picture was nowhere to be seen.

When Ida Jackson inquired about their missing photo to Dean Stebbins, Jackson was directed to President Barrows. In her 1984 oral history at The Bancroft Library, she recalls his exact response of why the members of AKA were omitted: they “weren’t representative of the student body.” According to Jackson, neither the sorority pictures nor the individual senior pictures of most black students made the yearbook.

The blatant racism and discrimination in Barrow’s reply was a reality for students of color. During the oral history conducted more than 60 years later, Jackson still could name nearly every black student at Cal, as there were only 17 African Americans enrolled in 1920. California, which Jackson had believed was the “Mecca” of racial equality and opportunity before arriving from the South, was very much enveloped in racial discrimination. She recalls that “there weren’t too many opportunities in other places because good old California proved not to be as liberal as my brother had thought it was, or painted the picture to us. Because people are people.”

Born in Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1902, Ida Louise Jackson credits her parents for teaching her honesty and outspokenness from an early age. She also recalls that her parents “put education ahead of everything,” believing that education would increase opportunity in a prejudiced system in which they themselves had struggled. Ida Jackson went to Rust College for two years, and graduated from a teaching course at New Orleans University (now Dillard). When she arrived in Oakland, California, in 1918 and requested a teaching application from the county superintendent’s office, they suggested she apply for a full California teaching credential. Eager to continue learning, Ida Jackson enrolled in the University of California, majoring in education. By 1921, she had formed Alpha Kappa Alpha to build a safe community for the small number of black students.

After graduating with a B.A in 1922 and M.A in 1923, Ida Jackson went on to apply for a teaching position in the Oakland public school system. At the time, she recalls that the general consensus was that a black person was not capable of teaching, especially in Oakland where there were very few black students that continued on to high school. She was rejected and told that she needed teaching experience. This led her to become the first black high school teacher in California at the racially segregated East Side High School for Mexican and African American students in El Cerrito in 1923. Once again, Jackson applied to teach in Oakland and was rejected. Even then, her fiery determination to teach in Oakland did not falter. She received help from President Walter Butler of the Northern California branch of the NAACP, who worked with influential white members of the Board of Education whom he personally knew in high school. Social reformer Anita Whitney intervened to endorse her teaching credibility. Only after such interventions did Ida Jackson receive an offer at the Prescott School in Oakland in 1926. Finally, she became the first black teacher in the Oakland public schools.

Ida Jackson remembers how her black students, whom she had encouraged to go into college when teaching in Prescott School in the late 1920s–1930, were discouraged by the counselor to follow in Jackson’s footsteps and become a teacher. This was because the opportunities were so far and few in between along the West Coast, that becoming a teacher was seen as an impossible career path for black students. Frustrated, Jackson found that mentality to be very narrow, and recognized that systemic racism had to be changed. Her philosophy was one of boldness and passion:

Have a certain amount of confidence in yourself . . . be willing to tackle whatever interests you, because you get something out of it whether you win all the way or not. It’s a valuable experience to go into unknown territory to sort of prepare yourself for anything that follows.

She then continued to devote her life’s work to creating more opportunities for black students. In 1934, Ida Jackson became the national AKA president, where she continued organizing chapters at other schools around the West Coast in LA, Arizona, Spokane, and Seattle. In that same year, Jackson initiated an Alpha Kappa Alpha summer school for rural teachers that began in Lexington, Mississippi, which brought volunteer teachers to equip local teachers and students in low-income areas. She strongly believed that “if the teachers were better prepared then they could inspire the youth to go ahead and get an education.”

However, she soon realized that the students not only were starved from education but also basic healthcare. Turning her focus to include welfare, Jackson, along with Dr. Dorothy Boulding Ferebee and AKA volunteers, began establishing child health care centers in rural areas. From the 1930s–1940s, Jackson became founder and director of the Mississippi Health Project, which expanded to include care for adults as well as children. Once again, she met obstacles with a fighting spirit. When it became increasingly difficult for clients to travel to the clinics, she helped the service evolve into a mobile center that moved between rural areas. Ida Jackson also was involved in forming a dental clinic for low-income families in Oakland. Meanwhile, her passion for education also did not dim. She spent a year at Columbia University and had gotten within two units of a doctorate in education, but did not officially obtain the degree because she could not afford the expense. Afterwards, Jackson held the position of dean of women at Tuskegee Institute, but ultimately returned to teach at McClymonds High School in Oakland upon retirement in 1953.

In addition to all this, Jackson was active in the National Council of Negro Women, where she strove to improve the economic and social conditions for low-income black women. She was also highly involved in the education department of the NAACP in their mission, as she described it, to “encourage more blacks to get higher education, and to sort of fight the prejudice that was in the schools.” In 1972, she donated her farm to UC Berkeley, requesting that the profits be used toward graduate scholarships for black students. Ida Jackson passed away on March 8, 1996, but her legacy lives on. In 2004, UC Berkeley unveiled the Ida L. Jackson Graduate House Apartments in her honor.

As a research assistant at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, my role is to research the oral histories of accomplished women associated with UC Berkeley and the UC system. This project was formed to celebrate the 150 years of women at Berkeley and highlight their struggles, accomplishments, and impact UC women have had. Personally, this research project has opened my eyes to the privileges I take for granted, and shut down misconceptions I had about history. Whenever I looked back in the past, even as a minority, I almost wanted to see racism as a distant problem, something far away from me. However, as we know, racial injustice can still be very much rooted in our systems and institutions. Thus, while it is not pretty, it is crucial to be reminded of the history of our schools and the institutions we take part in, and realize the inequalities that our very own students and communities may be facing. Ida Louise Jackson was a powerful woman who rejected racial discrimination in education and health as the status quo. Thus, her fighting spirit and unrelenting determination can be inspirational for us all to stand up for what we believe in.

Deborah Qu is a rising sophomore at UC Berkeley and is majoring in psychology.

Bibliography

Jackson, Ida Louise. “Ida Louise Jackson: Overcoming Barriers in Education.” Interview by Gabriella Morris in 1984 and 1985. Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1990.

Smith, Jessie Carney. Notable Black American Women. United States: Gale Research, 1992.

Find this and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

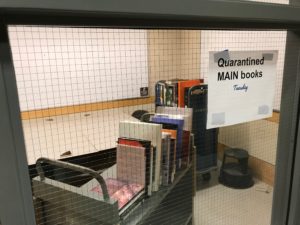

“A bit surreal” – a return to campus

Dispatch and photos by Peter Basmarjian, Social Sciences Division Student Supervisor

Being back on campus after almost four months has been a bit surreal. Last week a handful of staff began the work of sorting and checking in all of the accumulated books that have been returned since March.

Recently returned items are quarantined separately for a week. Then books are checked in and sorted by division.

Here are a few more scenes from around the Library. The janitorial staff did an incredible job cleaning the library from top to bottom and the plants in the AIDS Memorial Courtyard have been recently watered and are doing well.

Presenting the Oral History Center Class of 2020

At the conclusion of every academic year, the Oral History Center staff takes a moment to pause, reflect on the interviews completed over the previous year, and offer gratitude to those individuals who volunteered to be interviewed. The names below constitute the Oral History Class of 2020. Please join us in offering heartfelt thanks and congratulations for their contributions!

We would also like to take this time to thank our student employees, undergraduate research apprentices, and library interns. It was a unique semester, topping off a busy and productive year, and they continued to come through for us, as they always do. We rely on this team for work that is critical to our operations: research, interview support, and curriculum development; video editing; writing and editing of abstracts, front matter, and transcripts; and more. They’ve even produced articles and oral history performances to share our work with wider audiences. We couldn’t do it without them!

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

The Oral History Center Class of 2020

Individual Interviews

Robert L. Allen

Bruce Ames

Samuel Barondes

Alexis T. Bell

Robert Birgeneau

John Briscoe

Willie Brown

George Miller

Michael R. Peevey

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel

Robert Praetzel

John Prausnitz

Zack Wasserman

Bay Area Women in Politics

Mary Hughes

California State Archives

Jerry Brown

Chicano/a Studies

Vicki L. Ruiz

East Bay Regional Park District

Glenn Adams

Ron Batteate

Kathy Gleason

Raili Glenn

Brian Holt

Diane Lando

Mary Lentzner

John Lytle

Beverly Marshall

Rev. Diana McDaniel

Roy Peach

Janet Wright

Economist Life Stories

George Tolley

Getty Trust

Peter Bradley

Kathleen Dardes

David Driskell

Melvin Edwards

Charles Gaines

Kenneth Hamma

Thomas Kren

David Lamelas

Mark Leonard

Richard Mayhew

Howardena Pindell

Michael R. Schilling

Joyce Hill Stoner

Yvonne Szafran

Global Mining

Bob Kendrick

Napa Valley Vintners

David Duncan

Paula Kornell

David Pearson

Linda Reiff

Emma Swain

SF Opera

Kip Cranna

David Gockley

Sierra Club

Lawrence Downing

Aaron Mair

Anthony Ruckel

SLATE

Susan Griffin

Julianne Morris

Yale Agrarian Studies

Marvel “Kay” Mansfield

Alan Mikail

Paul Sabin

Ian Shapiro

Helen F. Siu

Elisabeth Jean Wood

Thank You

Student Employees

Max Afifi

Gurshaant Bassi

Yarelly Bonilla-Leon

Jordan Harris

Abigail Jaquez

Nidah Khalid

Ashley Sangyou Kim

Devin Lizardi

JD Mireles

Tasnima Naoshin

Lydia Qu

Lauren Sheehan-Clark

Librarian Interns

Jennifer Burkhard

Charissa Fitzpatrick

Undergraduate Research Apprentices

Corina (Mei) Chen

Nika Esmailizadeh

Evgenia Galstyan

Emily Keats

Esther Khan

Emily Lempko

Atmika Pai

Samantha Ready

Kendall Stevens

Real Voices in History

by Ricky J. Noel

We asked our awardee of the Carmel and Howard Friesen Prize in Oral History Research, Ricky Noel, to share how he found the oral histories he used, and his approach to incorporating them in his research paper. Read Oral History Center Director Martin Meeker’s award announcement. And hats off to Ricky!

My paper would not have been nearly as thorough if I hadn’t found these oral histories.

When I began research for my term paper I did not initially think to look in the Oral History Center’s archives for my primary sources. My class was centered on U.S. and Middle East relations and I had chosen oil as the foundation of my paper. Despite being familiar with the OHC collections through my library work, I didn’t think that their archives would have much that wasn’t U.S. centric.

I started with some general search terms and quickly realized that the results were plentiful but not necessarily related to my topic. It was easy to skim through the search results and identify what was relevant, but nothing initially stood out to me. There was however an oral history collection I found in the “Projects” section of the OHC website under Commerce and Industry: “Health and Disease in Saudi Arabia: The ARAMCO Experience 1940s–1990s.” Aramco happened to be one of the major oil companies discussed in my sections, and healthcare was an interesting perspective with which to approach the assignment.

Searching through an oral history may seem a bit daunting at first; the Aramco volumes were each roughly 700 pages long. However, the Health and Disease volume was available digitally in the archives and had drop down menus for each section and interviewee, which made it much easier to search for information related to my specific thesis, without me having to read through the entire collection.

I used this collection as the foundation for my paper by incorporating the actual voices of the interviewees and how they viewed their experiences in the company. I then applied outside secondary and primary sources to build my argument, as well as context. What I aimed for was to use the actual interviewees in the oral history (with quotes, paraphrasing) as a way to build an individualized view of how they viewed their work and applied it to the broader themes I had outlined in my thesis. My paper would not have been nearly as thorough if I hadn’t found these oral histories. The OHC is an incredibly useful source for researchers and I encourage anyone to learn more about oral histories and how they can be used in one’s projects. I will say that first person voices enliven history and the OHC has plenty of them available to use.

Finally I would like to thank the Friesens for this wonderful prize and for providing additional focus on the resources of the Oral History Center for scholarly research.

Ricky J. Noel is starting his final year at Berkeley. He is majoring in history with a Latin American concentration.

Perseverance Against the Odds: UC Berkeley Professors Natalie Zemon Davis and Elizabeth Malozemoff

by Deborah Qu

Twenty-twenty has proven itself to be a challenging year, starting with the spring semester at UC Berkeley suddenly moving online to accommodate for the shelter-in-place order during a worldwide pandemic. Stressed, demotivated, and anxious, many of us students had to balance school on top of financial, familial, mental health, and other issues. Needless to say, I was extremely touched by the flexibility and continued commitment that many of my professors exhibited this semester. Twenty-twenty is also the 150th year of the University of California opening its doors to women, and I am lucky to be part of a project of the Oral History Center to identify all the interviews of UC-related women in its collection. While doing this research, I found myself especially interested in the stories of UC Berkeley women faculty. Many of these women were pioneers in their own fields at the time, or pursued their passion for learning despite great adversity.

The oral history of historian Natalie Zemon Davis reminded me that what is first seen as unconventional or disadvantageous can sometimes actually be an opportunity. As the only woman in a department of men, she used her position to include more units focused on women in history and expanded gender studies classes at UC Berkeley. Professor Elizabeth Malozemoff reminded me that learning is a valuable treasure and that pursuing education could continue at any age. Going back to school and earning her degrees at Cal, she rebuilt her life with such an unbroken positive attitude after leaving her home in Russia because of the chaos from the Bolshevik Revolution. Reading about their life experiences not only made me proud to be a Golden Bear, but also gave me encouragement and a sense of hopefulness for the future.

Natalie Zemon Davis

Professor Natalie Zemon Davis is a social and cultural historian who specializes in Early Modern History. In 1968, she arrived at UC Berkeley as a visiting professor and the only woman in the History Department at the time. She attained full professorship later in 1971. In addition to Berkeley, she has taught at Brown University, the University of Toronto, and Princeton University. In her interview conducted by the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library in 2003, Professor Davis recounts the difficulties attaining equality as a woman in a male-dominated field. This, in turn, sparked an interest in teaching history with a focus on women.

From the start, Davis did the unconventional. She chose to go into graduate school while also being married, which were seen as two distinct and diverging pathways for women in the 1950s. She recalls in her oral history interview that while her teachers were “not optimistic about women marrying and having children and having a career, because they had taken other paths,” Davis was not interested in following norms. Her marriage was founded on “egalitarian ideals.” She was one of the very few female students studying archival social history. Although the professors treated her seriously, she admitted that there was a difference in social attitude and treatment, stating “they just didn’t think about what it might be like to be a woman student.” But her interest in history meant more to her than adhering to the status quo. She remembers, “there was no way I was going to be stopped….I loved my work so much.”

Instead of allowing the challenges of being one of the only women to overwhelm her, it actually sparked an interest to bring a greater emphasis on the perspective of women into the historical discourse. Working with female graduate students in 1966 at the University of Toronto, Davis studied the experiences of women with children working toward their Ph.D., hoping to raise awareness to daycare needs. She was one of the first to hold undergraduate economic history classes with a focus on women “as central characters,” by adding topics regarding women poverty and labor services. Her integrity behind her courses stood out; she taught what she thought was important and interesting without expecting that it would lead to recurring courses. At UC Berkeley, Professor Davis taught the Reformation course, “Society and the Sexes in Early Modern Europe,” which looked at the likeness and differences between genders, garnering attention for the expanding field of gender studies. Professor Davis was involved in the Academic Senate Committee on the Status of Women, an initiative committed to hiring more women in academic departments.

While Davis’s accomplishments already make her story noteworthy, her confident attitude to pursue her passion was what really left a strong impression on me. As someone interested in pursuing a career in academia but also sometimes racked with self doubt about my ability, I admired the simplicity in her love of history and gender studies. And I certainly felt pride for UC Berkeley when she praised the institution for its “open” environment, which she felt gave her a space to experiment with understanding history and culture through the perspective of women.

Elizabeth Malozemoff

As the spring semester continued on, I, like many others, was having difficulty staying motivated for my online classes. But, when I read through Professor Elizabeth Malozemoff’s oral history interview, I was suddenly reminded of the simple fun and joy learning can bring. Before Malozemoff went on to become a Russian Culture and Literature professor at UC Berkeley, she was born in Tsarist Russia in 1881. Growing up as a daughter of a seamstress who interacted with the wealthy, she became familiar with the entrenched classism within Russian society, specifically the contempt toward the meshchane, or whom she called the “petty bourgeois.” She explained in her oral history how the meshchane were seen as “the people who cannot rise from the ground, who are only interested in eating and sleeping, they have no interest in anything culture or in anything spiritual.” According to Malozemoff, this only gave people of the meshchane a strong desire to break free from such conceptions. Her mother, who could speak multiple languages but could not read or count well, had a “determination to give the children the best education possible,” because it was a dream her “mother had when she was a young girl.” Malozemoff believes that her class upbringing became interlaced with her identity starting from a young age, and subsequently acted as fuel and passion for her teaching.

Malozemoff began teaching at age 19 in St. Petersburg, later founded a kindergarten in 1915 for workingmen’s children while holding adult classes for miners, and also was principal for a high school at Lena Gold Mines from 1918–1920. However, her world was upturned when the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 first brought on unwanted cuts and limitations to her school, and then the “saddest tragedy of my life.” She recalls in the interview how she heard from her younger brother:

I received a telegram from him announcing the deaths of the five dearest people in my life. There had been a massacre around the estate. The Bolsheviks massacred my mother, my two sisters, and even the nurse of my little nieces, and then my brother was killed. My nephew, a boy of twelve, jumped out of the window when these Bolsheviks came and started to use their rifles. The two little nieces, twins, crawled into a stove and they stayed there during the night. The whole place was ransacked.

The violence and political unrest ultimately led Malozemoff to leave her life and established career in Russia to escape with her family through Siberia, Mongolia, China, and Japan, until they eventually reached San Francisco in 1920. Heartbroken, she had to start her life from scratch.

Yet at the same time Malozemoff recalls that she entered the United states with a sense of fresh optimism, believing that it was “a blissful country for us that would give us a chance to develop our capabilities.” As she began to acculturate into American life, she made it her purpose “to give in written form American culture to the Russians, and also to bring Russian culture to my American audience, my American friends and the American people.” She also felt a sense of inferiority in her education, that her teaching in the “lower classes” and caring for her children had left her “so ignorant, not being up-to-date with literature, with music, with historical events which had occurred during the ten years.” Specializing in Russian culture, she enrolled and received her B.A. in 1922 at age 41, her M.A. in 1929, and her Ph.D in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in 1938, all of which were obtained at the University of California, Berkeley. From 1935–1950, Malozemoff became a Russian language and culture professor, continuing her longterm passion for teaching and introducing Russian culture to students at Cal.

Needless to say, her journey was marked with obstacles. Malozemoff recalls the confusing process of adapting to American culture, stating that “during the first months in a foreign country you don’t understand what’s going on, not knowing the language, and not knowing many of the ways of life.” Regardless of what she had experienced, her optimism stood out to me. In her interview she remembers her horror while walking through a neighborhood during Christmastime, misinterpreting the wreaths hung on doors as a symbol for death in the family, instead of a festive decoration. While she saw it later as a “funny mistake,” it is one of countless examples of the little confusions an immigrant experiences while trying to adapt to a new culture in day-to-day life.

Perhaps it is the stories hinting at her ability to connect with her students, the wisdom she gained from traveling, or her tenacity to learn and find new forms of teaching that I find most admirable. Or maybe it is her mantra that she proved to live by that I find most striking. Her favorite saying goes, “step forward, always forward, in all circumstances in life.” According to her, that is precisely what she did, “trying to be alive with continuous desire to be human and humane, in steps forward the simplification and service to the people.”

Deborah Qu just finished her first year at UC Berkeley and is majoring in psychology. As a part of the celebration of 150 years of women at Berkeley, Deborah is researching the Oral History Center’s vast archive to identify women in the collection with a relationship to UC Berkeley.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.