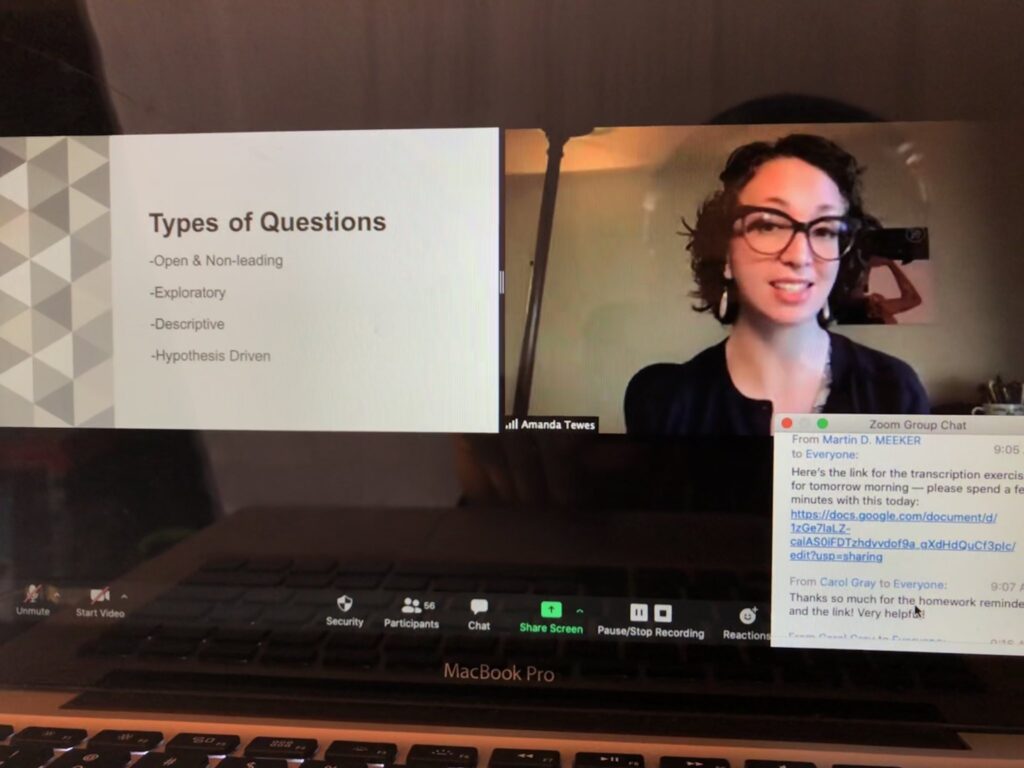

The OHC is offering interactive, online versions of our educational programs again this year due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

CLOSED: Advanced Institute: August 8–12, via Zoom

NOTE: Applications to the Advanced Institute are now closed and the wait-list is full. We look forward to seeing you at our Introductory Workshop and Advanced Institute in 2023. Dates for these programs will be announced in the future.

The Oral History Center is offering an online version of our one-week advanced institute on the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history. This will take place from August 8–12, 2022. Due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, the Advanced Institute will be held online.

The cost of the Advanced Institute has been adjusted to reflect the online nature of this year’s program. Tuition is $600. See below for more details, including scholarship opportunities.

The institute is designed for graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, university faculty, independent scholars, and museum and community-based historians who are engaged in oral history work. The goal of the institute is to strengthen the ability of its participants to conduct research-focused interviews and to consider special characteristics of interviews as historical evidence in a rigorous academic environment.

We ask that applicants have a project in mind that they would like to workshop during the week. All participants are required to attend small daily breakout groups in which they will workshop projects. In the sessions, we will devote particular attention to how oral history interviews can broaden and deepen historical interpretation situated within contemporary discussions of history, subjectivity, memory, and memoir.

Overview of the Week

The institute is structured around the life cycle of an interview. Each day will focus on a component of the interview, including foundational aspects of oral history, project conceptualization, the interview itself, analytic and interpretive strategies, and research presentation and dissemination.

Instruction will take place online. Seminars will cover oral history theory, legal and ethical issues, project planning, oral history and the audience, anatomy of an interview, editing, fundraising, and analysis and presentation. During workshops, participants will work throughout the week in small groups, led by faculty, to develop and refine their projects.

Participants will be provided with a resource packet that includes a reader, contact information, and supplemental resources. These resources will be made available electronically prior to the Institute, along with the schedule.

Applications and Cost

The cost of the institute is $600. We are offering a limited number of participants a discounted tuition of $300 for students, independent scholars, or those experiencing financial hardship. If you would like to apply for discounted tuition, please indicate this on your application form and we will send you more information. [Update March 10, 2022: Discounted tuition slots are now full.]

Please note that the OHC is a soft money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants other than our limited number of scholarships. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

Questions?

Please contact Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu with any questions.

CLOSED: Introductory Workshop: Feb. 4, 2022, 8:30 a.m.–2:30 p.m. via Zoom

Join us next year!

The 2022 Introduction to Oral History Workshop will be held virtually via Zoom on Friday, February 4, from 8:30 a.m.– 2:30 p.m. Pacific Time, with breaks woven in. Applications are now being accepted on a rolling basis. Please apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

This workshop is designed for people who are interested in an introduction to the basic practice of oral history and learning best practices. The workshop serves as a companion to our more in-depth Advanced Oral History Summer Institute held in August.

This workshop focuses on the “nuts-and-bolts” of oral history, including methodology and ethics, practice, and recording. It will be taught by our seasoned oral historians and include hands-on practice exercises. Everyone is welcome to attend the workshop. Prior attendees have included community-based historians, teachers, genealogists, public historians, and students in college or graduate school.

Tuition is $150. Please note that the OHC is a soft money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

If you have specific questions, please contact Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu.