Author: Paul Burnett

Now Available! The Japanese American Internment Sites: A Digital Archive

The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce the completion of the “Japanese American Internment Sites: A Digital Archive” which includes important historic materials from our archival holdings that are now available online.

The project was generously funded as part of the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program and includes approximately 150,000 original documents from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (BANC MSS 67/14 c). The records represent the official documentation of the U.S. War Relocation Authority. Existing from March 1942 to 1946, the WRA was created to assume jurisdiction over the relocation centers, administered an extensive resettlement program, and oversaw the details of the registration and segregation programs.

“We are very grateful to The National Park Service for funding the digitization of these important historical documents.” said Mary Elings, Assistant Director and Head of Technical Services at The Bancroft Library. “We hope researchers will find the content informative and that we will see new digital scholarship emerge as a result of this material now being available in digital form.”

The project builds upon two previous grants conducted between 2011-2017 to digitize 100,000 documents from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study and 150,000 original items from Bancroft’s archival collections including the personal papers of internees, correspondence, extensive photograph collections, maps, artworks and audiovisual materials. Together, these collections bring the total number of digitized and publicly available items to about 400,000 and form one of the premier sources of digital documentation on Japanese American Confinement found anywhere.

The Japanese American Evacuation & Resettlement Digital Archive website, http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/jacs provides context to this rich and substantive digital archive, and directs users to collection guides on the Online Archive of California and curated searches of digitized objects on the Calisphere website.

—

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

New Oral History: MaryAnn Graf, “The Life of a Wine Industry Trailblazer”

We are pleased to release our oral history interview with MaryAnn Graf. MaryAnn Graf was the first woman to graduate the University of California Davis in Food Science with a specialization in Enology, which she did in 1965. She went on to work for commercial wine operations such as Gibson and United Vintners before being hired as winemaker for Simi Winery in 1973.

After leaving Simi, she established with Marty Bannister the company Vinquiry, which provided laboratory and wine consulting services to wineries throughout California. She retired from Vinquiry in 2003. In this oral history, Graf discusses her upbringing in California’s Central Valley, her undergraduate education at UC Davis, her early jobs formulating flavored wines, her move into varietal wines at Simi and work with leaders including André Tchelistcheff, and her establishing a consulting wine laboratory. She also discusses her unique position as a woman in the wine industry at a time in which most every job was dominated by men.

This interview with MaryAnn Graf represents just our most recent interview on the California wine industry, which has been a major focus of the Oral History Center for many decades. We are excited to report that more fascinating interviews in this area are currently in production and we are actively seeking partners who might help us by sponsoring more interviews. Please contact OHC director Martin Meeker for more information: mmeeker@library.berkeley.edu

WILLIAM REESE: A MAN WHO LOVED AMERICANA

by Steven Black, Bancroft Acquisitions

In quick succession, joy followed by tears, June 2nd and 4th, 2018.

At the Annual Meeting of The Friends of The Bancroft Library, Carla A. Fumagalli was introduced as this year’s awardee of the William S. Reese Fellowship in American Bibliography and the History of the Book in the Americas.

For a number of years Bancroft has been favored to host a Reese fellowship, along with other peer institutions, including American Antiquarian Society, the Beinecke library at Yale University, the John Carter Brown library at Brown University, the University of Virginia Library, the Huntington Library, the Bibliographical Society of America, and the Library of Congress .

Two days later news reached us of the passing of William Reese, one of the foremost U.S. antiquarian booksellers and bibliographers of our time.

Celebration, punctuated by grief and mourning, then, hopefully, more celebration (if not stoic acceptance) —is a rhythm we accept without relish. Closer to home, our mortal persistence was tested in February with the passing of eminent Berkeley bookseller, Ian Jackson, who was a familiar presence to many on the UC campus and in bookshops around town.

Bancrofters most recently saw Bill Reese in February at the California International Antiquarian Book Fair in Pasadena.

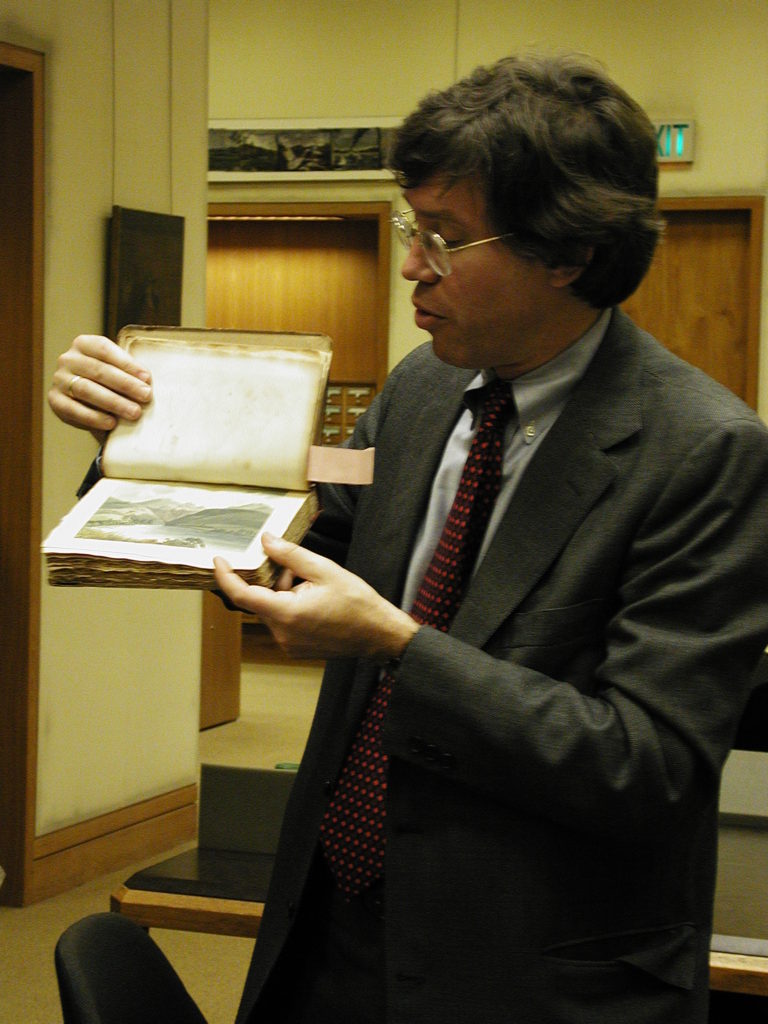

Looking back on decades of our working together to build the Bancroft Collection of Western Americana, brought to mind a special visit he made to the Library in February 2001. His talk was about major and minor colorplate travel and exploration books on the American West, using a small selection assembled for display on that occasion.

Here are some pictures of this informal exhibition, after hours in Bancroft’s Edward Hellman Heller Reading Room.

Out from the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

Out from the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

“They couldn’t believe that I could win,” Rosalind Wiener Wyman remembered about her unexpected election to the Los Angeles City Council in 1953. Over the course of several interviews in 1977 and 1978, Wiener Wyman shared her personal and political triumphs and losses, which culminated in her oral history, “It’s a Girl”: Three Terms on the Los Angeles City Council, 1953-1965; Three Decades in the Democratic Party, 1948-1978. Wiener Wyman’s memories as a woman politician at midcentury are part of the Oral History Center’s California Women Political Leaders Oral History Project, which documented “California women who became active in politics during the years between the passage of the women’s suffrage amendment and the…feminist movement.”

Wiener Wyman came by her passion for politics honestly. Speaking of her parents, she reflected, “I always felt their activities and interest in politics was steeped in me. In my baby book, at two, I’m looking up at a picture of FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt]. Most kids in their baby book are not looking at posters of FDR.”

While a student at the University of Southern California, Wiener Wyman and the campus Democratic Club worked on Harry Truman’s 1948 campaign. But her political work began in earnest when she met her “heroine,” Helen Gahagan Douglas, then a member of Congress representing California and running an ultimately unsuccessful campaign for Senate in 1950. Wiener Wyman was disappointed in Gahagan Douglas’s showing on the campaign trail and confronted her about it. Gahagan Douglas replied, “ ‘If you know so much about a campaign, here, here’s a card. Come see this lady and get into my campaign.’ ” Wiener Wyman took up the challenge and threw herself into this work, hanging posters and driving Gahagan Douglas to her campaign stops. Laughing, Wiener Wyman recalled, “I remember once changing my hose in the car with her in a parade. She took mine and I took hers. Crazy things a woman candidate worries about.”

Wiener Wyman began her own political career fresh out of college. In 1953, she ran a grassroots campaign for Los Angeles City Council that relied solely upon door-to-door conversations with her constituents, without the benefit of media coverage or traditional advertising. Her victory over established, male candidates was such a surprise that she recalls from the night of the election:

As the bulletins were handed to [Joe] Micchice, [a local radio announcer], he said, “I’m sure that the votes are on the wrong name.” So, he, during the night, would give my vote to Nash. Finally he put his hand over the mike–we have this on a record which is so wonderful–and he said, “Is this bulletin right?” Or, “Who the hell is Wiener?”

After a runoff election, Wiener Wyman came out on top. Of this dark horse winner, the Los Angeles Times declared, “It’s a girl!”

Wiener Wyman stood out as the youngest member and only woman on the Los Angeles City Council from 1953 to 1965. Notably, Wiener Wyman did not see herself as a victim of gender discrimination; rather, she saw her break with other council members in terms of age and experience. This, despite the fact that other city council members voted to not allow her personal leave to enjoy her honeymoon. Additionally, Wiener Wyman had to contend with the fact that “the only toilet was off the council chambers and that was for the men.” She recalled, “That became an incredible issue that got around town. Where was I going to go to the bathroom? I thought I would die over that!”

During her time in office, Wiener Wyman famously led the charge to entice the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles, making it the first Major League Baseball team west of the Mississippi River. Although the displacement of Mexican American families from Chavez Ravine and the building of Dodgers Stadium was controversial then and now, Wiener Wyman defended her support for this civic boosterism and the prestige it brought to Los Angeles. However, she conceded of her leadership on this fight: “it probably cost me some of my popularity.”

Beyond her twelve years in elected office, Wiener Wyman’s political legacy perhaps best lies in her fundraising efforts for other Democratic candidates. During one memorable event in the backyard of her Los Angeles home, Wiener Wyman and her husband, Eugene Wyman, hosted a dinner for Democratic congressional candidates and charged $5,000 a couple, an unthinkable sum in 1972.

Rosalind Wiener Wyman’s life and career point to the many ways in which California women have and continue to engage in political life, as well as the rich collection of political history at the Oral History Center. As we approach the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, documenting the experiences of these women political leaders will become all the more important.

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian

From the Director: Oral History and the Berkeley Tradition

From the Director: Oral History and the Berkeley Tradition

On the evening of Thursday April 26th, the staff of the Oral History Center hosted our annual event in which we take the opportunity to express our gratitude to our remarkable narrators and our generous sponsors. I’ll also usually say a few words about the center and provide an overview of the scale of the work that we do for the benefit of those who might only know it just from the vantage point of being interviewed. Preparing my remarks was easy this year because 2018 happens to be a pretty special year at Berkeley: it marks the 150th anniversary of the founding of the university! What follows is an edited version of my remarks:

This evening I want to spend a few minutes sharing my thoughts on the essential role that this oral history program has played in this history of this university. See, the University of California was founded on March 23, 1868, just a little over 150 years ago. And while what we now know and love as the Oral History Center wasn’t established for another 90 years, in some very important ways, this program has been with the university since the beginning: it has been with the university through the first and second-hand experiences of those who built the university into what it is today, transmitted over the past 64 years through recordings now archived in the Bancroft Library.

Physicist Raymond Thayer Birge, from an interview completed in 1960, conveys his knowledge of the university’s earliest years from his departmental perch: “The Department of Physics is very old. It goes back to John Le Conte, the first man appointed to the faculty of the original University. He was appointed professor of physics, he was also acting president for those first two or three years. Then later on, I after we had had two or three presidents; he was president, I think for five years, Then he got fired, although that doesn’t appear on the public record, but he actually did. [But] he remained [on faculty] until I think 1891, when he died; and he was the first member of the original faculty to die, as well as being the first one to be appointed.”

The Faculty Club, designed by famed architect Bernard Maybeck, is a treasured institution on campus. In our 1962 interview with Leon Richardson, we get a first-hand account of its founding: “Well, I was one of the founders of the Faculty Club, and I can tell you just how it began. Three or four of us saw a little (tumbled down … unoccupied) cottage on the southern rim of the campus and we said among ourselves, ‘Couldn’t we rent one of those cottages, maybe for $5 a month and then hire a caterer to come and give a luncheon to us five days a week?’ Anyway, we hired the cottage and got the caterer and it went well. From that we began to expand and expanded until the day came when we got the regents to build us a clubhouse on the campus with Maybeck as the architect.” In another passage from the Richardson interview, we learn Jane Sather gave a considerable sum to pay for the bells of Sather Tower but when money was left over, the decision was made to build the structure that has welcomed visitors to campus since 1910, now called “Sather Gate.”

William Dennes, who arrived on campus as a junior professor of philosophy in 1915, many decades later recalls what he found: “The campus was mostly like a neglected ranch: foxtail and other dried grass in August, when the term then began, ragged and for the most part not gardened, [but there was] an ivy bed around California Hall. And Benjamin Ide Wheeler was very concerned that the boys and girls shouldn’t make paths across his ivy bed!”

Although the International House movement began in New York City, Berkeley established the second house in the country and our I-House remains a lively center of intercultural exchange today. In a 1969 oral history, Harry Edmonds offers his recollections: “One frosty morning in September, 1909, I was going up the steps of the Columbia Library … when I met a Chinese student coming down. I said, ‘Good morning. ‘ As I passed on, I noticed out of the corner of my eye that he had stopped. So I stopped and went back to him. He said, ‘Thank you for speaking to me. I’ve been in New York three weeks, and you are the first person who has spoken to me’ … I went on about my errand but had no sooner gotten around back of the library that I realized something extraordinary had happened. Here was a fellow, this student, who had come from the other side of the world, … he had been here for three weeks, and no one had spoken to him. What a tragedy. I retraced my steps to find him to see if I could be of some help, but he had vanished in the crowd. That evening when I went home, I told my wife of my experience. She asked if I couldn’t ‘do something about it.’” Before too long, Edmonds played an instrumental role in founding the International House movement.

I could go on quoting from interviews describing the rise of the Free Speech Movement and Ethnic Studies on campus, examinations of the Loyalty Oath and the creation of the several new campuses of the UC System, and, yes, there is a very good account of the founding of the Oral History Center, but I’ll stop here. These quotes were drawn from much longer oral histories which are just an exceedingly small sample of the 4000 interviews in our collection that document not only the history of this university but also the region, the state, and frankly, the world.

So what is to be gained from these interviews? Are they just colorful anecdotes or do they offer something greater?

If you get the chance to listen to the interviews, the cadence of the speech found in the oral histories is strikingly different today, as often is the vocabulary. We are in the process of digitizing these interviews, so in the years to come you’ll be able to listen to their words, how they spoke those words, and begin to explore how we might gain new understandings through voice and affect. These interviews also provide information not readily available in the public record, as hinted at in Birge’s recollection of John LeConte’s career challenges. Moreover, they offer detailed accounts of everyday life — the kinds of things that provide texture to our understanding of the past but might be ephemeral and thus exist only in our memories, otherwise disappearing when we do too and not documented in writing. They reveal the moments of inspiration behind the ideas, institutions, and innovations of the university; they reveal origins often shrouded in the mystery of epiphany and immediate experience. These interviews give experts the opportunity to share their ideas, discoveries, and challenges in everyday language, thus giving non-experts the opportunity to learn about complex and fascinating things outside of jargon-filled publications, for example. And, finally, they tell us just how Sather Gate came to be!

In 2018, 150 years since the University of California was established, I encourage you to dig into our collections and read the first person accounts of how and why Berkeley became one of the greatest universities in the world.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

Checking in with Summer Institute Alum Marc Robinson

Checking-in with Summer Institute Alum Marc Robinson

When Marc Robinson traveled from Spokane, Washington to Berkeley, California in August 2017, it was in the name of narrative history. He came to the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute to work on his project about black student activism in the late 1960s, which was somewhere between dissertation and manuscript. He had done some interviews while earning a PhD in American Studies from Washington State University, but felt like he was just scratching the surface. Like many who understand the value of oral history in doing contemporary history, he wanted to talk to more people, get a broader range of narratives, and explore the way that some of the stories he was recording contradicted archival documents.

Robinson’s doctoral research was about student activism on campuses in the Northwest, particularly around those who were in the Black Student Union during a time of social and political unrest in the 1960s. He focused on two campuses, one urban — the University of Washington — and one rural — Washington State University. After doing several interviews with students who were active there, Robinson wanted to broaden his cohort of narrators to include not only black students, but their allies and the larger community of people connected to the Black Student Union, but were not students themselves.

He came to the Summer Institute looking for more training in longform life history interviews and left the program thinking deeply about what this type of interview can really provide to a researcher. “Narratives aren’t really telling the Truth, but their recollection of what happened as it pertains to them,” he says. He found that some of the narratives that he had collected challenged the materials he had found in the archives, which made him see interviewing as an opportunity to understand the complexity of memories. The program taught him to expect this complexity and see oral history as having transformative power. Another takeaway? The importance of the tech side of interviewing. “It made me think more about headphones, mics, the quality of sound, and knowing your equipment,” he says.

Since his time in Berkeley, Robinson was hired for a tenure track faculty job in the History Department at Cal State University San Bernardino (congratulations, Marc!), where he’ll start in the fall of 2018. He plans to continue working on his project and is interested in getting his students involved in the interviewing process. “It can be a really valuable teaching tool,” he says. He hopes to get his students involved in projects that illuminate local history, current events, and the community, something that Cal State San Bernardino has a track record of.

Please join us in congratulating Robinson on his new job! Look out for his book, which is on track to be out by 2020. We’re excited to see what he learns from his next round of interviews and what they can teach us about the times we are living in now.

Interested in learning more about Robinson? About the SI or joining us in 2018?

Follow him on Twitter @MarcARobinson1, and apply for the SI here.

Bancroft Welcomes Digital Project Archivist

Please join us in welcoming Lucy Hernandez as our new Digital Project Archivist on the NPS-funded Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) grant project. Lucy will manage the two-year JACS project to digitize materials from Bancroft collections related to the Japanese American Internment. She will begin her new appointment on Monday, May 15.

Lucy comes to us from her position as the Archivist at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida where she worked on processing, digitizing, and providing reference services for archival collections. Prior to that, Lucy worked as the Archivist at the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge for 10 years.

She earned her Bachelor of Arts in Economics and Art History from University of California Santa Cruz and a Masters of Arts in Art History from California State University, Northridge, and she is certified by the Academy of Certified Archivists.

The Bancroft Library Announces New Head of Technical Services

After an extensive national search, the Bancroft Library is pleased to announce the appointment of Mary Elings as the Head of Bancroft Technical Services and Assistant Director of The Bancroft Library. In this role, Elings will provide leadership for Bancroft’s largest division responsible for technical services operations for rare books, archival, and special collections as well as for the use of advanced technology to establish administrative and intellectual control over Bancroft collections.

Before taking on this role, Elings served as the Interim Head of Bancroft Technical Services from 2016 to 2017. Prior to that, she held the position of Bancroft’s Principal Archivist for Digital Collections and served as Head of the Digital Collections Unit. Elings began her career at Bancroft in 1996 as a pictorial archivist before expanding her expertise in operational support for public services, archival information systems, digital research collections, and born-digital archives. Her leadership in developing digital research collections has not been limited to Bancroft but has also served the University Library, the Berkeley campus, and the University of California system. Her teaching in the field of librarianship, as adjunct faculty for library and information science schools at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and Syracuse University in New York, has enhanced her leadership in this area. Her current research focus is on developing “research ready” digital archival collections in support of computational research needs and working with faculty and students on collaborative research projects in the digital humanities.

Elings succeeds David de Lorenzo, who served as the Head of Bancroft Technical Services from 2001 until 2016 when he was appointed the Giustina Director of Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Oregon.

Elings can be contacted at melings@berkeley.edu.

Remembering Gene Brucker (1924-2017) and the Department of History Oral History Project

Remembering Gene Brucker (1924-2017) and the Department of History Oral History Project

We note with sorrow the passing in July of Professor Emeritus Gene Brucker, historian of Renaissance Florence, one of our esteemed oral history narrators, and the instigator and longtime supporter of our oral history series on the Department of History at Berkeley.

The oral history series had its beginning in 1995, when Gene was designated as the Faculty Research Lecturer. Instead of focusing his lecture on Renaissance Florence, he turned his historian’s eye on Berkeley, on his own department, where he had arrived in 1954 in time to participate in its postwar flowering into one of the most distinguished history programs in the US. In his research he found few remaining written records; surprisingly, the department had discarded a great deal of its own history. He turned to informal interviews with his colleagues to develop his lecture. Later discussion with his friend Carroll Brentano, historian of the University of California and wife of Gene’s colleague, Robert Brentano, led to the idea for an oral history project under the auspices of the Regional Oral History Office, predecessor to OHC. I was fortunate to work with them as the project director and interviewer. For over a decade Gene and Carroll served as project advisors. They convinced their colleagues to themselves become subjects of historical research, and they facilitated the funding that made the project possible.

Among our wealth of oral histories on the University of California, OHC’s series on the Department of History at Berkeley stands out. With lengthy biographical oral histories of nineteen professors of European, American, and Asian history, and one faculty wife, all of whom came to Berkeley in the late 1940s to the early 1970s, it the most extensive of our several series on university departments. And thanks in great part to the vision of Gene Brucker, the interviews are extensive in scope as well: along with a deep dive into the personal background, education, and scholarly trajectories of each narrator, they discuss postwar departmental history in some detail, including governance, key hiring and promotion decisions, curriculum and teaching. And they examine Berkeley’s academic culture, the informal and formal associations and interactions that invariably affect scholarship. They also explore the involvement, often intense in this postwar generation, in broader campus governance and major campus controversies from the loyalty oath, free speech, and antiwar protests to the belated hiring of women faculty in the 1970s.

Having contributed so much to the project, Gene Brucker, a man who really did not like to talk about himself, finally agreed, reluctantly, to record an oral history in 2002. I met with him for eleven sessions, documenting his journey from farm boy in Cropsey, Illinois—via the University of Illinois, Oxford, Princeton, and the Florentine archives—to a career as a distinguished historian of Florence and preeminent citizen of the Berkeley campus. Like others in the series, it is replete with insights into academic culture, the historians’ craft, and the postwar years of growth and tumult on the Berkeley campus. Gene’s oral history and others in the Department of History project. See also “In Memoriam: Gene Adam Brucker”

Ann Lage, interviewer emeritus, October 24, 2017.

From the Oral History Center Director – OHC and Education

For an office that does not offer catalog-listed courses, the Oral History Center is still deeply invested in — and engaged with — the teaching mission of the university.

For over 15 years, our signature educational program has been our annual Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. Started by OHC interviewer emeritus Lisa Rubens in 2002 and now headed up by staff historian Shanna Farrell, this week-long seminar attracts about 40 scholars every year. Past attendees have come from most states in the union and internationally too — from Ireland and South Korea, Argentina and Japan, Australia and Finland. The Summer Institute, applications for which are now being accepted, follows the life cycle of the interview, with individual days devoted to topics such as “Project Planning” and “Analysis and Interpretation.”

In 2015 we launched the Introduction to Oral History Workshop, which was created with the novice oral historian in mind, or individuals who simply wanted to learn a bit more about the methodology but didn’t necessarily have a big project to undertake. Since then, a diverse group of undergraduate students, attorneys, authors, psychologists, genealogists, park rangers, and more have attended the annual workshop. This year’s workshop will be held on Saturday February 3rd and registration is now open.

In addition to these formal, regularly scheduled events, OHC historians and staff often speak to community organizations, local historical societies, student groups, and undergraduate and graduate research seminars. If you’d like to learn more about what we do at the Center and about oral history in general, please drop us a note!

In recent years we have had the opportunity to work closely with a small group of Berkeley undergrads: our student employees. Although the Center has employed students for many decades, only in the past few years have they come to play such an integral role in and make such important contributions to our core activities. Students assist with the production of transcripts, including entering narrator corrections and writing tables of contents; they work alongside David Dunham, our lead technologist, in creating metadata for interviews and editing oral history audio and video; and they partner with interviewers to conduct background research into our narrators and the topics we interview them about. With these contributions, students have helped the Center in very real, measurable ways, most importantly by enabling an increase in productivity: the past few years have been some of the most productive in terms of hours of interviews conducted in the Center’s history. We also like to think that by providing students with intellectually challenging, real-world assignments, we are contributing to their overall educational experience too.

As 2017 draws to a close, I join my Oral History Center colleagues Paul Burnett, David Dunham, Shanna Farrell, and Todd Holmes in thanking our amazing student employees: Aamna Haq, Carla Palassian, Hailie O’Bryan, Maggie Deng (who wrote her first contribution to our newsletter this issue), Nidah Khalid, Pilar Montenegro, Vincent Tran, and Marisa Uribe!

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center