Author: Paul Burnett

OHC Director’s Column – December 2019

From the Director…

The Oral History Center Top 10 of 2019

With Thanksgiving falling late on the calendar this year, all of the sudden things are feeling very rushed in the lead up to 2020. Despite that feeling, your friends here at the Oral History Center set aside a few moments to reflect on some of the more memorable episodes of 2019. This year we again conducted about 500 hours of interviews and did a whole lot more too, such as produced two seasons of our podcast series, The Berkeley Remix, taught scores of eager students about oral history, and traveled the nation to record our interviews. The countdown that follows, then, is just a snapshot of those times that made us laugh, let us weep, and forced us to sit back in awe of the impactful research we do and the wonderful stories we are honored to record.

- OHC historian Shanna Farrell started an oral history book club. Her first selection was Patrick Radden Keefe’s remarkable new book, Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland (if you want to know more, check out the not-so-oral history transcript of our conversation).

- The work of the Center was featured wide and far through a variety of media, providing an ever-larger opportunity for folks to engage with the work that we do. OHC oral histories were featured on podcasts such as East Bay Yesterday, California Report Magazine, and The Dropout (about Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes); and news of our work was featured in California Magazine and regularly on Berkeley News and even a few times on the homepage of the Berkeley website, thanks to the efforts of our newest employee, Communications Manager Jill Schlessinger.

- A 2019 highlight for OHC historian Roger Eardley-Pryor was his interview with H. Anthony “Tony” Ruckel, former President of the Sierra Club. Ruckel helped pioneer the then-nascent field of environmental law. Roger recalled, “During his interview, Tony explained how, in 1969, as a ‘green’ 29-year-old lawyer, he brought the precedent-setting Parker v. United States case under the Wilderness Act of 1964 to protect land near Vail, Colorado that eventually became Eagle’s Nest Wilderness. To prepare for his interview, I read Tony’s book on environmental law, Voices for the Earth (2014), while backpacking through the Emigrant Wilderness in the high Sierra Nevada, just north of Yosemite National Park. What better place to read about Tony’s efforts to preserve wilderness than a designated wilderness area!”

- On occasion, we have the opportunity to host a special event celebrating the completion of an oral history. In August, we fệted Anne Halsted, the community advocate who has spent tireless decades serving many nonprofit organizations and government agencies striving to improve communities in the Bay Area. After the formal presentation, those attending were treated to spontaneous memories and tributes; perhaps the one that got the most applause was when someone proclaimed that Halsted should have been our first female President! This event also marked the official kick-off of our new oral history project on Women in Politics — check back in 2020 for more news on this.

- East Bay Yesterday host Liam O’Donoghue was the keynote speaker at the 2019 Summer Institute and provided the group assembled with a complex view into the history of our region that clearly demonstrated the power of oral history to bring the past alive.

- Shanna Farrell reflected on 2019 and concluded a highlight for her was traveling to New York to interview the celebrated abstract sculptor Mel Edwards. Farrell wrote, “His work is so powerful and he’s so intelligent that meeting him in person was a really gratifying experience. Participating in the Getty Trust oral history project, even in a small way, has been one of the best oral history projects on which I’ve worked.”

- HBO released to wide-acclaim its popular miniseries Chernobyl, based on the collection of oral histories Voices of Chernobyl. The author of this book, Svetlana Alexievich, won 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature in part for this work. (This book will be the first OHC book club selection of 2020 — why not read along with us?)

- When asked about 2019, OHC historian Paul Burnett was momentarily stumped, but then replied, “In an annual roundup, it’s a bit unusual to write about something that began in the fall of 2017, but my work with UC Berkeley engineering scientist George Leitmann qualifies. At twenty-three hours, his oral history is a very deep dive into one person’s life story. More than that, George and I spent many hours poring over photo albums, looking at artifacts, and planning the final look of the interview volume. His oral history is extraordinary, not only because it showcases an extraordinary person, which he is; but also because of the extraordinary history he witnessed.”

- Producing our own podcasts were definitely a highlight. We released two seasons this year — 6 full-length episodes! The first was called Let There Be Light: 150 Years of UC Berkeley. This featured three episodes edited and narrated by three OHC historians (Paul Burnett, Amanda Tewes, and Shanna Farrell); the podcasts provided three snapshots of Cal’s history at 150 years. The second season was Hidden Heroes, which drew upon the interviews of the East Bay Regional Park District Oral History Project. Produced by Shanna Farrell and Francesca Fenzi, these three episodes built upon the stories told in the interviews, illustrating, we think, the transformative power of oral history and the important role of parklands in our lives.

- And, drumroll, the Number One on this list comes from yours truly. We’ve made no secret of the fact that in 2019 we partnered with local public radio station KQED and the California State Archives to conduct Governor Jerry Brown’s oral history. The interview is done and we’re currently editing the transcript for release in January (finger’s crossed!). I joined KQED’s Scott Shafer and our own OHC historian Todd Holmes in asking the questions, and, as you’ll see when it is released, there were highlight points-a-many in the result exchanges. But one special moment I’ll recall for a good long time was when the dialog changed from historian-and-governor to gardener-and-gardener. During one lunch break in the blazing heat of summer at the governor’s ranch, Brown admitted to me that he was concerned about the progress of his tomatoes: were those blotches a disease? Why was there no fruit yet? I was happy to provide a quick consultation and when I returned a few weeks later, I was relieved to see a healthy bush ripe with cherry tomatoes!

I hope that everyone in the reach of this newsletter had the good fortune of experiencing their own top 10 moments of 2019 and wish more such positive memories and proud accomplishments for 2020. It is imperative that I recognize the OHC Top 10 could not have happened without the support of so many people: the OHC staff is second-to-none and are a pleasure to work with; our student employees continue working quietly but so professionally and productively behind the scenes; and, without question, our narrators’ gift of their time and their memories is the beating heart of our work, and always will be. Our generous partners and individual sponsors make this work possible, and we are deeply grateful for the support that they provide. We hope that you, too, will remember the Oral History Center as you make your year-end gifts — and we make it easy for you to do so here. We’ve got some great things planned for 2020, so please continue on this journey will us in the months and years to come.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center

Remembering a First Response to the Epidemic on World AIDS Day

In 1988, the World Health Organization established World AIDS Day, one of eight major global health campaigns begun by the United Nations. It stands today as a reminder that, after forty years, tens of millions of people have died of HIV/AIDS, and approximately 37 million are currently living with the disease. It also should remind us of how terrifying this disease is, how it hurts those the most who have the fewest resources with which to defend themselves, and how we are nowhere near an end to the spread of HIV and the suffering it causes.

Last year, the Oral History Center released a 7-episode podcast about the first efforts to understand, track, and treat a mysterious new illness that was killing gay men in San Francisco. Based on the three dozen interviews conducted by Center historian Sally Smith Hughes, First Response: AIDS and Community in San Francisco highlights both the larger context of the arrival of the epidemic and the on-the-ground drama of the physicians, nurses, epidemiologists, and laboratory researchers who were fighting for scarce resources while also fighting the disease.

For decades now, HIV/AIDS has been evolving into different disease, as it spread around the world into new social, economic, technological, and cultural contexts. By 2010, new infections in the United States were three times as likely to be among African American and Latino populations as among white men, for example.

There is therefore a lot of work for us to do at the Oral History Center to map the past thirty years of the epidemic. Sadly, however, many of the themes of First Response are still relevant today: the stigmatization of the disease, a reluctance to pay for the public-health and primary-care interventions necessary to check the spread of HIV, and our general struggle to address the larger context in which survivors of HIV find themselves. For now, we will be working with partners to develop curriculum content for Grade 11 classrooms across the country around the First Response podcast and our collection of interviews. If you would like to help with this work developing assignments and content for educators, please contact Paul Burnett at pburnett@berkeley.edu.

New Release Oral History: George Miller

George Miller: ‘Gamos’ and Other Tales from Sam’s Grill

by Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

The title of this particular oral history reveals not only something about its content, it provides some hint about the circumstances of the interview itself. In this transcript, you’ll see the usual Oral History Center (OHC) template of question followed by answer and so forth, but befitting the setting of the interview — San Francisco’s historic Sam’s Grill — this exchange was more a wide-ranging conversation. It turns out that George Miller, our featured narrator here, doesn’t much like the spotlight. Although he has many accomplishes to boast, he would prefer to talk ideas and give space to those things that he finds important, interesting, confounding, and amusing.

You will learn in this interview that George Miller first came to know the Oral History Center in the course of serving as a volunteer archivist, processing collections in our home, The Bancroft Library. Surrounding himself with many other very interesting and accomplished individuals, Miller asked the then OHC director if we might like to do an oral history with Thomas Graff, a man who was deeply active in environmental politics and a leader of the Environmental Defense Fund. It was agreed that Graff was a very worthy subject and Miller generously sponsored the interview. Over the following decade, Miller nominated — and underwrote — many more oral histories, thus helping OHC maintain its operations while also contributing to expansion of the oral history collection at Berkeley. As of 2019, the list includes: Jake Warner, Rick Laubscher, Will Travis, Joe Bodovitz, Anne Halsted, Michael Teitz, Jim Chappell, John Briscoe (in 2020), and, last but not least, a forty-hour interview with Warren Hinckle. As the interviewer for the Bodovitz and Travis interviews, I first met Miller around 2014. I recall an informal tipple at the Faculty Club cocktail lounge when I think I finally pieced it together: 1. He was not George Miller, the congressman; 2. Despite his rather informal façade, he is a very serious thinker; and 3. That plaque above a urinal in the men’s restroom at the club? It honored none other than George Miller, our partner in these interviews.

After engaging with Miller over the years, I suggested that he should sit for an oral history interview himself. This suggestion, and the many that followed, were rebuffed with silence. As time went on, however, I began better to grasp the necessity of conducting his oral history, despite the refusal of the potential narrator, Miller himself. So, I pressured a bit more and enlisted the support of a few allies. He finally agreed to entertain the idea, and after a few lunches at Sam’s to hash over the idea, he ultimately consented. He reasoned, to paraphrase, it might be better to do something and regret it, than not do it at all. Still, Miller made it clear that he didn’t want a conventional interview that would run point-by-point through his life. He also wanted to do these sessions at Sam’s. Neither scope nor setting would be conventional, but that was fine with me. As you read the interview, you might see that my typical interviewing structure tended to impose itself on the proceedings, but the setting and, certainly, the narrator shook things up a bit. What you have here, then, in just a bit over five hours, is an opinionated, informed, humane, rollicking, and oftentimes deeply humorous running commentary on a wide-ranging set of specific events and big themes. We get a glimpse into the history of investing and the psychology of the market; we learn of Miller’s commitment to the environment and his iconoclastic effort to restore Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley (by tearing down a massive dam); we gain insight into Bay Area urbanism and the challenges faced by those trying to improve it; and we are treated to a unique philanthropic vision for the University of California, Berkeley, and beyond. But even more than these topics, this interview invites you to pull up a stool at the bar and hear the musings and be regaled with well told stories by someone who really has seen it all.

OHC Director’s Column – November 2019

From the Director:

Preserving Veteran Experiences for Future Generations

It was the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month that the armistice ending World War I took effect. In the ensuing years this was celebrated, first, as Armistice Day, and, now, as Veteran’s Day. On this day we commemorate and remember those men and women who have served in the armed forces. Although the Oral History Center has no “veteran’s oral history project” per se, we proudly have documented the lives and service of hundreds of military men and women in multiple projects throughout our collection, and in observance of this year’s holiday, we’d like to highlight some of those for you here.

When the Oral History Center was established sixty-five years ago, World War I already was nearly forty years in the past. I was not able to locate any oral histories in our collection with those who served in the US military at that time, but the life and times of The Great War does appear in our interviews, and from some pretty interesting angles too. Our 1987 interview with Charles Blaisdell, Jr. offers a view into immediate prewar Germany, around the time of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, as well as his observations of World War I from outposts in India and China. A memoir from 1976 provides another unique perspective on World War I, this time from a young man living in pre-Soviet Russia, Ivan Stenbock-Fermor.

The collection becomes much more substantial in its coverage of World War II, both of those who served in the military and who assisted with the homefront effort. Of the latter group, any serious researcher must contend with the Rosie the Riveter / World War II Home Front oral history project. This project, completed only in the last few years, is OHC’s largest project to date, resulting in hundreds of individual interviews. Along with scores of interviews with those who worked in wartime industries, this project also features a handful of interviews with women who served in the military, such as army recruiter Mary Cohen, who later went on to place veterans in jobs; or served in some auxiliary role, such as Anita Christiansen and Mary Highfill, both of whom volunteered with the USO; or Grahame Crichton Coffey, who joined the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) in 1943 and continued her service for the duration of the war.

In dozens of additional interviews, men detail their service in the war and bravery in many of the great battles. Walter Newman, for example, provides a harrowing, awe-inspiring account of the Invasion of Normandy in June 1944; around the town of Saint Lo, Newman was shot through the lung and gravely injured, spending many months hospitalized (see the video below). He recuperated fully and went on to work for the welfare of veterans throughout his life and was even honored with the French Legion of Honor medal in 2009. Our recent oral history with UC Berkeley Mechanical Engineering Professor George Leitmann also offers a riveting first-person account of the Battle of Colmar and the liberation of Europe. The fact that both Newman and Leitmann were young Jews fighting the Nazis adds an extra dimension to these dramatic tales.

The story of American veterans did not end with World War II, and the OHC collection includes scores of oral histories with those who have served in Korea, Vietnam, and the Gulf War, among other conflicts. Our project documenting the history of the Oakland Army Base includes interviews covering all of these conflicts, but has a special focus on the Korean War and Vietnam War eras, the time at which the base was the largest military port operation in the world. Gordon Coleman, an Oakland native and graduate of UC Berkeley, served in Korea in the immediate wake of the ceasefire. George Bolton, who was interviewed for this project, was raised in Oakland and was drafted into the army in 1963 where he served for two years, including some time in these early years of the Vietnam War. Grant Davis served in the Air Force during the Vietnam War, and then went on to have a civilian career at the Oakland Army Base. All three men speak about their military careers from the perspective of African Americans who experienced integration, and racism, while in the service.

These interviews are just one way — perhaps only one small way — in which the Oral History Center, and by extension UC Berkeley, chooses to honor our veterans and remember their service to our country. Further, we are aware that those whom we had the chance to interview were those who survived the battles, the wars, and the hardships; they returned home, but many others did not. Because they are the ones who lived to tell those stories, we take seriously our role in preserving them for you and future generations to hear.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

Robert Kendrick: Mine Design, Planning and Supervision from High Mountain to Deep Jungle, 1950s-2000s

I was looking back over my original 2014 proposal for the The Global Mining and Materials Research Project, to which this new Bob Kendrick oral history is the latest addition. There was this passage about the project’s purpose: “to document expertise that can speak to the political, environmental, legal, social, and economic changes that surrounded mining exploration, permitting, production, processing, and remediation over the last thirty years.” This oral history is certainly about all of that, but it is also a life history in the fullest sense. The more proximate impetus for the interviews, as it too often is, was the narrator’s failing health.

In the lead-up to the interview sessions, Bob was concerned that he had not prepared enough, that he might not remember enough, or tell the stories well enough. But he was sure that he wanted to say some very specific things about his life experiences. We worked together with his wife of 65 years, Marian, and their sons Peter and Mike, to assemble material to frame the set of interviews that would be held in a western suburb of Phoenix. Marian and Bob then welcomed me into their home in February of this year for just two days and an afternoon. They had a dining room table covered with boxes of papers, photo albums, and artifacts, such as core samples from a gold mine, the hide of an anaconda and a stuffed piranha. For better or worse, I positioned two of Gary Prazen’s bronze sculptures of miners in the background behind Bob in the interview frame. All around the house were Marian’s paintings depicting beautiful scenes from some of their long sojourns in South America, Central Asia, Siberia, Canada, and all over the United States.

Bob and Marian did work all over the world, but one of the clear messages we get from a life history is the sense of origin, of place. There is a distinct mountain sensibility about this oral history. The place and time where Bob grew up, Leadville, CO in the 1930s and 40s, was a somewhat forbidding place, on a kind of vertical frontier, a sometimes dangerous place. Bob grew up with danger, but I suspect he also grew up with some variety of mountain culture. People did things up there that were difficult, sometimes because they had to, but sometimes precisely because they were difficult. Bob relished physical challenges, which perhaps prepared him for other kinds of challenges later in life.

There are parts of this oral history that are raw. There were stories that were difficult for Bob to recount, but that he wanted to tell nevertheless. These days, there is little talk about “character,” so little that I don’t know that we can easily define it anymore. When I heard Bob talk, still with a lot of grief after so many years, about what it’s like to tell a family that their loved one has been killed in the mine of which he was in charge, I thought I might have caught a glimpse. It occurs to me that these interviews were perhaps one more difficult thing he wanted to do. But this oral history is, to paraphrase Bob, also full of good things.

Bob is survived by his wife Marian, and his children Mike, Peter, Melissa, Rob, and Gina.

The Oral History Center wishes to thank the Freeport Foundation and Stanley Dempsey for their support of the Center and for making this oral history possible.

Oral history and the Second Golden Age of Radio?

A long while ago, my colleague Shanna Farrell told our group about one of her pet peeves, the overuse / misuse of the term “oral history” in the media. She is certainly right about the increased use of the term. A cursory search of the mass-media landscape includes some fun stories in Forbes on the week Wayne Gretzky hosted Saturday Night Live, in Billboard on the time Kanye West rushed the stage at the Video Music Awards, and in vulture.com (New York Magazine) on a scene in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, in which an actor narrowly avoids having a pencil pierce his eyeball.

As I was looking at these pieces, it occurred to me that what journalists mean by “oral history” is simply a more extensive use of quotations and a lighter touch with the narrative. But it’s still, of course, journalism. These are “thick descriptions” of a moment in time, not the life histories oral historians usually do.

We in the profession of oral history, however, are at a bit of a messaging disadvantage. After all, mainstream journalism, even in the age of social media, is the ultimate mainline to the public. In fact, journalists still for the most part shape and define what we call “the public.”But do all of these examples constitute a misuse of the term “oral history?” The piece on The Dark Knight, for example, is nothing more than a series of quotations from people interviewed for the article. How different are these from the secondary outputs developed within the field of oral history, such as the Oral History Center’s own podcasts?

There is a real appetite for what oral historians do, and it’s growing. Part of me welcomes this misuse of so-called oral history, as long as we have the opportunity to correct misconceptions about our nuts-and-bolts work, i.e., the co-creation of more in-depth life histories, and to highlight the core fact of our privileging the voice and authority of the narrator over our own.

With our hectic, multitasking lives, punctuated by the forced downtime of gridlocked traffic and monotonous subway rides, we’re living in a strange second Golden Age of Radio. Archival oral history projects have a great shot at reaching these audiences of bored commuters, pensive gardeners, and late-night snugglers if we can broaden our notion of how to package and curate the wonderful materials we’ve helped to make with our narrators.

OHC Director’s Column – September 2019

An oral history of the Zombie War!?

No, UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center isn’t about to undertake an oral history project on humanity’s battles with zombies. But this was the subtitle to the 2006 novel by Max Brooks, World War Z, that was later made into a big-budget movie starring Brad Pitt as, what else, a former UN employee-turned-zombie eradicator. Having experienced both versions, I can say without qualification that the book was far superior to the movie, in part because the book attempted to take the oral history dimension a bit more seriously—while not skimping on fun or sensation. “Oral history” in this case was the novel’s conceit: first person accounts collected in the wake of the war (spoiler alert: the zombies lose), edited and spliced together in an attempt to create a narrative of the madness. But, really, is this “oral history”?

In recent years, “oral history” has moved from academic jargon to pop culture ubiquity. While there have been moments in the past when oral history-like projects have broken through (think Alex Haley’s Roots), only now are we seeing, for example, “An Oral History of the Time Wayne Gretzky Appeared on SNL,” an article which appeared last month in Forbes (of all places!). Surely my colleagues and I are thrilled that oral history appears to be having a moment. Less often do I get that crinkled look on someone’s face when I tell them, “I’m an oral historian.” They’re not as likely to ask, “Does that have something to do with… dentistry?” But. We are not entirely comfortable with what this increase of recognition means. People link “oral history” to any number of cultural products, maybe especially StoryCorps, which is regularly featured on NPR. Like World War Z, however, even StoryCorps is quite different from the way in which professional, university-based oral historians do our work.

Within the oral history community there is on-going conversation about just what elements comprise “best practices.” Yet, there is some baseline agreement as evidenced by the Best Practices document approved by the members of the Oral History Association in 2018. At the Oral History Center, our definition of “oral history” begins with a set of core practices and procedures. These practices set our work apart from anthropologists, most journalists, and, yes, fictional chroniclers of the zombie wars.

Oral history at Berkeley begins with creating a project and determining its size and scope, which might result in fifty interviews or just one. We select the narrators, or interviewees, and ask them to sign a letter of informed consent. This letter details their rights and responsibilities, including the fact that they can withdraw from a project at any point prior to its completion. The interviews are conducted, typically in two-hour sessions, and are recorded on video, unless the narrator wants audio-only. All interviews are transcribed then lightly edited by our staff before being given to narrators for review and approval. We finalize the transcripts, deposit them in The Bancroft Library, and usually make them available to world-at-large through our website. So, for us, “oral history” is defined by three key elements: thorough research and planning; narrator consent at the beginning and approval at the conclusion of the project; and broad accessibility to the finished and approved transcript (and, increasingly, to the original recording as well). Once these bona-fide oral histories have been completed and offered up for use, hungry minds around the world are given the opportunity to create their own interpretive oral history projects on any number of subjects from the banal to the profound, from the tiny to the grandiose—but let’s all hope not on any zombie war past, present, or future.

In this issue of our monthly newsletter, we ponder the question of “what is” and “what is not” oral history. As you’ll notice, we are not doctrinaire, but we do take this question very seriously and think that it is a useful starting point for any conversation about what it is that we do.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

New Release Oral History: Jesse Choper on the Constitution, Legal Education, and Horse Races

The Oral History Center is pleased to release our life history interview with Jesse Choper. Jesse Choper is the Earl Warren Professor of Public Law (Emeritus) at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, where he also served as dean from 1982 to 1992.

Choper was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1935 to immigrant parents from Lithuania. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and alongside his studies served on the law review and lectured at the Wharton School. Following his graduation in 1960, he served as law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. He has authored numerous influential books and articles on constitutional law, including the role of the Supreme Court, the religion clauses of the Constitution, the eleventh amendment, as well as casebooks on constitutional and corporate law. This autobiographical oral history covers the full sweep of his life and work as a legal scholar, educator, and administrator. In this interview, Dean Choper talks about his upbringing and evolving relationship to Judaism; his education and teaching experience and philosophy; his clerkship for Chief Justice Warren; the numerous complex issues he faced as faculty and dean of the law school; the issues behind his books and articles on constitutional law, including freedom of religion, the establishment clause, contraception and abortion, individual rights, federalism, and separation of powers; reflections on changes over the past several decades to the Supreme Court, tenure, and approaches to constitutional law; and his role on the California Horse Racing Board.

Choper was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1935 to immigrant parents from Lithuania. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and alongside his studies served on the law review and lectured at the Wharton School. Following his graduation in 1960, he served as law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. He has authored numerous influential books and articles on constitutional law, including the role of the Supreme Court, the religion clauses of the Constitution, the eleventh amendment, as well as casebooks on constitutional and corporate law. This autobiographical oral history covers the full sweep of his life and work as a legal scholar, educator, and administrator. In this interview, Dean Choper talks about his upbringing and evolving relationship to Judaism; his education and teaching experience and philosophy; his clerkship for Chief Justice Warren; the numerous complex issues he faced as faculty and dean of the law school; the issues behind his books and articles on constitutional law, including freedom of religion, the establishment clause, contraception and abortion, individual rights, federalism, and separation of powers; reflections on changes over the past several decades to the Supreme Court, tenure, and approaches to constitutional law; and his role on the California Horse Racing Board.

The Oral History Center has interviewed Dean Choper on two previous occasions, once for the Law Clerks of Chief Justice Earl Warren project and then again for the Athletics at UC Berkeley project.

Dr. Robert Allen’s Port Chicago and Civil Rights Archive and Oral History Collection

By Julie Musson and Lisa Monhoff

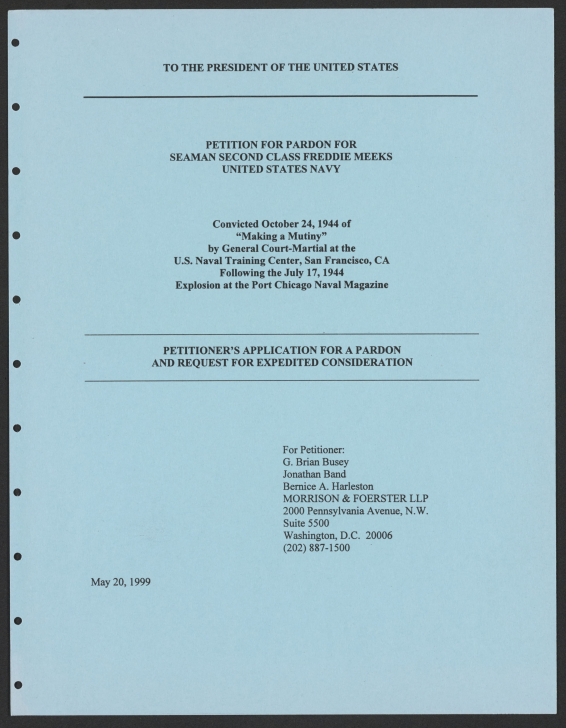

This July marks the 75th Anniversary of the Port Chicago Naval Magazine disaster, a massive explosion that resulted in the largest loss of life on the U.S. mainland during WWII. The explosion happened while African-American sailors were loading a munitions ship in the Suisun Bay. Munitions detonated and two cargo ships exploded killing 320 and injuring 390 sailors and civilians. After the explosion, hundreds of African-American servicemen refused to return to segregated, unfair, and unsafe work conditions and 50 of those sailors held out for better work conditions. In response, the Navy charged the men with mutiny and sentenced them to 15 years of hard labor. The disastrous event at Port Chicago and media coverage of the ensuing mutiny trial was a pivotal moment in the discussions of racial inequality in the U.S. and contributed to desegregation in the Navy beginning in 1946.

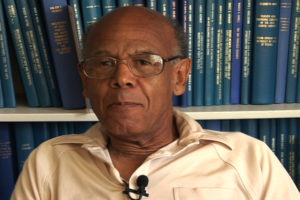

In 2016, the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial under the stewardship of the National Park Service acquired the Dr. Robert Allen Port Chicago and Civil Rights Collection. The collections comprised of 35 linear feet of research archives and 34 hours of oral history interview content produced by Dr. Robert L. Allen as the result of over 40 years of primary research, documentation and scholarly works. The work of Dr. Allen to understand and publicize the disaster and the mistreatment of the sailors culminated in the publication of The Port Chicago Mutiny in 1989 and has continued with decades of appeals for official pardons and exoneration for those charged with mutiny.

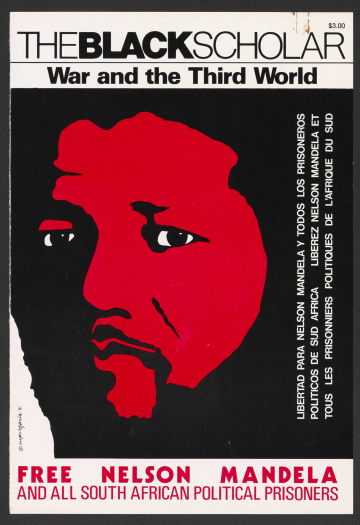

The Robert L. Allen papers on Civil Rights consist of correspondence, primary research, writing and teaching materials created by Dr. Allen in his capacity as activist, editor, writer and educator. Dr. Allen’s body of work includes several books written and published about civil rights and labor leaders, including Bay Area activists Lee Brown and C.L. Dellums. He also served as Senior Editor and writer for many years at The Black Scholar, co-founded a small press with Alice Walker called Wild Trees and taught in the Ethnic Studies and African-American Studies programs at the University of California, Berkeley.

In collaboration with the National Park Service, the Bancroft Technical Services processed and digitized the National Park Service’s Dr. Robert Allen Port Chicago papers and the Bancroft’s Robert L. Allen papers on Civil Rights. The Oral History Center digitized and transcribed the Port Chicago Oral History interviews.

Links to the resources are below.

The Bancroft’s Robert L. Allen papers http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8sq966g/

NPS Allen (Dr. Robert) Port Chicago Papers http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8f195h3/

Oral History Center Port Chicago Interviews http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library/oral-history-center/projects/poch

OHC Director’s Column – July/August 2019

“How can one best teach oral history?” This is the question that OHC staff asks every year in anticipation of our annual Advance Oral History Institute, held the week of August 5th this year. Oral history is many things — a research methodology, a mode of inquiry, a field of study, a way of engaging with people — so how does one approach communicating a viable path toward the completion of successful interviews?

A few generations of practitioners, theorists, and teachers have approached this challenge in any number of ways. Some recommend book study to first learn the issues and questions — the overall discourse of oral history — as the best way to achieve sure-footing; others insist that competence in oral history, being primarily about human exchange, is most easily achieved through practice, learning as you go; and some contend that oral history is nothing more than historical research, so pursue it as one would archival study. The correct answer is probably all of the above, or some dynamic mixture thereof.

In 2014, after hosting probably ten Institutes, new and veteran OHC staff gathered, led by then-new Institute Director Shanna Farrell, to refashion the program and attempt to come up with an optimal way to ‘teach’ oral history over the 5-day program. Farrell came up with the notion of matching the flow of the week to the life-cycle of the interview: Monday focuses on oral history foundations — concepts, theories, and ethics; Tuesday details approaches to project planning and conceptualization; Wednesday naturally examines the complexities of the interview itself; Thursday we delve into strategies for analysis and interpretation of those interviews; and Friday we bring it together by considering various oral history outputs, such as transcripts, podcasts, and books. Along the way, participants engage with the theoretical and methodological literature of oral history; they have the opportunity to witness a ‘live interview’ and then practice interviews of their own; and in small workshop groups they are invited to consider how oral history research might augment and, potentially, transform their own research projects.

In 2014, after hosting probably ten Institutes, new and veteran OHC staff gathered, led by then-new Institute Director Shanna Farrell, to refashion the program and attempt to come up with an optimal way to ‘teach’ oral history over the 5-day program. Farrell came up with the notion of matching the flow of the week to the life-cycle of the interview: Monday focuses on oral history foundations — concepts, theories, and ethics; Tuesday details approaches to project planning and conceptualization; Wednesday naturally examines the complexities of the interview itself; Thursday we delve into strategies for analysis and interpretation of those interviews; and Friday we bring it together by considering various oral history outputs, such as transcripts, podcasts, and books. Along the way, participants engage with the theoretical and methodological literature of oral history; they have the opportunity to witness a ‘live interview’ and then practice interviews of their own; and in small workshop groups they are invited to consider how oral history research might augment and, potentially, transform their own research projects.

Over the past year or so, in our newsletter we have featured profiles of several Institute ‘graduates’ — individuals who have achieved great things through their own hard work, work that we like to think the Institute has informed and maybe even improved. The plan for this year is to live-tweet parts of the Institute, so please follow us on twitter if you don’t already. And while our 2019 Institute is sold-out, it is not too early to plan for 2020 (dates coming soon!).

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director