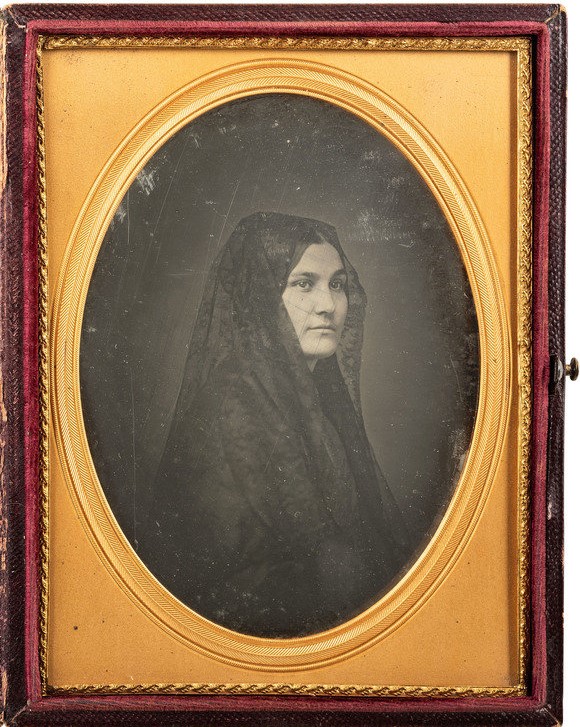

Women’s history month is the perfect time to announce an exciting addition to Bancroft Library’s collection of daguerreotype portraits. At the end of 2023 the library was able to acquire a beautiful 1850s portrait of a Californiana: doña Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson, also known as Anita.

In this large (half plate format) daguerreotype of about 1850-1855, Anita wears a lace mantilla, in the Spanish fashion. A beautiful large daguerreotype like this was an extravagance at the time, and the portrait is all the more evocative because Anita, tragically, died within a few years of its creation.

Fortunately, quite a bit is known about her life. Anita was born into the prominent de la Guerra family of Santa Barbara in 1821 -– the same year the Spanish colonial period ended and control by an independent Mexico began. She was married at age 14, to an American trader and businessman named Alfred Robinson, 14 years her senior. This wedding is described in Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, so we have an unusually detailed account of what was a grand occasion.

She and her husband snuck away from her family in 1838, leaving their baby daughter behind with her grandparents. Anita, age 15, wrote ”We have left the house like criminals and left here those who have possession of our hearts.” Various writers have interpreted these circumstances differently but, whatever the reason for this strange departure, Anita spent the next 15 years in Boston and the East Coast, seemingly eager to return home, but continually disappointed in the hope. It is hard to imagine that her life was entirely happy, in spite of the steady growth of her family and the prosperity and social prominence the Robinsons and de la Guerras enjoyed.

Having borne seven children, and having witnessed from afar (and apparently mourned) the transition of her homeland from Mexican territory to American statehood, Anita finally returned to California in the summer of 1852. It is likely she had her daguerreotype portrait taken at this time, in San Francisco, although it could have been taken back east. Sadly, she lived just three more years in California, dying in Los Angeles in November 1855, a few weeks after giving birth to a son. She is buried at Mission Santa Barbara.

A study of Anita’s life was published by Michele Brewster in the Southern California Quarterly in 2020 (v.102 no. 2, pg. 101-42) . Read more of her story!

With such a fascinating and relatively well-documented life, we’re thrilled to have Anita’s beautiful portrait here at Bancroft. It joins other de la Guerra family portraits, as well as numerous papers related to the family, including “Documentos para la historia de California” (BANC MSS C-B 59-65) by her father, José de la Guerra y Noriega.

Two of Anita’s sisters had “testimonias” recorded by H.H. Bancroft and his staff; one from Doña Teresa de la Guerra de Hartnell (BANC MSS C-E 67) and another from Angustias de la Guerra de Ord (BANC MSS C-D 134).

Anita’s daguerreotype itself presents an interesting conundrum and history. The photographer is unknown, as is common with daguerreotypes. The portrait has been known over the years because later copies exist in several historical collections, including the California Historical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Bancroft Library’s own Portrait File.

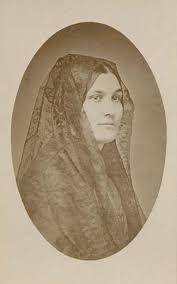

The daguerreotype acquired last Fall was owned for some decades by a collector. When he acquired it, it was unidentified. Later he encountered a reproduction of it in a historical publication, and thus had the identification of the sitter. Each of the known copies is somewhat different from the others. In her article, Brewster reproduces the copy from the Massachusetts Historical Society. It is a paper print on a carte de visite mount bearing the imprint of San Francisco photographer William Shew, at 115 Kearny Street.

Based on this information, Brewster attributed the portrait to Shew; however, Shew is merely the copy photographer. A daguerreotype, largely out of use by the 1860s, is a unique original, not printed from a negative, so only one exists unless it is copied by camera. The carte de visite format was not in widespread use until the 1860s, and Shew was not at the Kearny address until the 1872-1879 period. So the photographer remains unidentified.

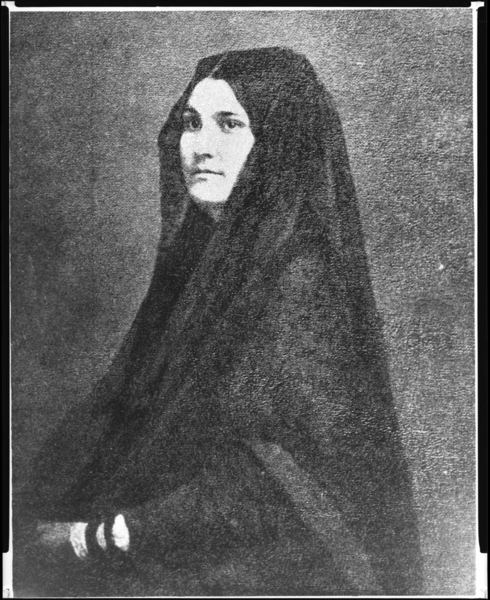

Another puzzle is posed by the early 20th century reproductions in the Bancroft Portrait File and the California Historical Society, which appear identical. These copies present a less closely cropped pose than the original daguerreotype, which is perplexing! Anita’s lap and hands are visible in the copies, but not in the daguerreotype. Although the bottom of the daguerreotype plate is obscured by its brass mat, there is not enough room at the lower edge to include these details.

How could a copy contain more image area than the original? Upon reflection, two possibilities come to mind:

1) the daguerreotype was copied in the 19th century and photographically enlarged, then re-touched or painted over to yield a larger portrait that included her lap and hand, added by an artist. This reproduction was later photographed to produce the copies in the Portrait File and CHS.

or,

2) the original daguerreotype included her lap and hand, and it was re-daguerreotyped for family members in the 1850s, perhaps near the time of Anita’s 1855 death. When the copy daguerreotypes were made, they were composed more tightly in on the sitter, omitting the lap and hands. The newly acquired Bancroft daguerreotype could be a copy of a still earlier plate – and this earlier plate could be the source of the later paper copy in the Portrait file.

This will likely remain a mystery until other variants of this portrait surface. Are there other versions of this portrait of Anita de la Guerra de Robinson to be revealed?

Reference

Brewster, Michele M. “A Californiana in Two Worlds: Anita de La Guerra Robinson, 1821–1855.” Southern California Quarterly 102, no. 2 (2020): 101–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27085996.