For the first time, the Oral History Center, or OHC, partnered with an artist named Emily Ehlen, who created ten graphic narrative illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project. The JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

Below is an interview with Emily Ehlen about her processes in creating such dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators. You can see and save copies of larger images of Emily’s artwork for the JAIN project in a separate blog post.

Artist Bio:

Emily Ehlen is best known for her colorful and whimsical illustrations using mixed media. Watercolor, ink, spray paint, and gouache are the primary mediums she uses for her traditional works, and she also integrates them in her digital pieces. She loves being positive and expressing her interests while using her surroundings as inspiration. To invoke curiosity and imagination, her drawings reflect an open view of the subject and are framed with pieces of expression and reality. Change and adaptability are a constant as she goes through various experimentations and approaches to her art.

Q&A with artist Emily Ehlen:

Q: What was your process for creating the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives artwork?

Emily Ehlen: My process started with selecting powerful imagery and phrases in relation to connecting themes found throughout the oral history transcripts. I composed thumbnails with the intent to represent the information clearly and use symbolism to convey the narrative. I wanted to use as much text from the source as I could, but I wanted to avoid it being too word heavy. It was a balancing act of editing the text and imagery to support each other in the composition and narrative. After developing and consolidating the initial drafts I moved on to tighter linework and color concepts. Once the colors were established, I inlaid patterns and handmade textures to add contrast between objects, panels, and the background. The handmade textures were made with ink washes and spray paint. The final step was applying shading and details to enhance the focus of each element while also keeping the flow throughout the entire composition.

Q: How was your work on this project similar or different to your prior art projects?

Emily Ehlen: This Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives art project was similar to the comic series Drawn to Art: Tales of Inspiring Women Artists that I worked on in 2021 for the Smithsonian American Art Museum. For that Smithsonian project, I drew a three page comic called “Weaver’s Weaver,” featuring Kay Sekimachi, a Japanese American artist. My process for both projects were pretty identical. Although, I think I had a little more freedom with expanding the storytelling elements working on the JAIN project comics. Overall, they were mutually great experiences that I am so grateful to have been a part of.

Q: How did engaging with the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives oral history transcripts shape the stories you chose to tell and some of the imagery you used in your graphic art?

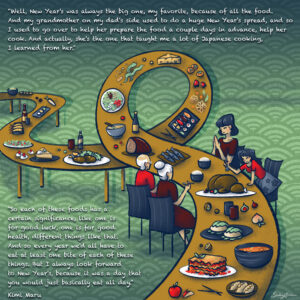

Emily Ehlen: When drafting the concepts of the illustrations, I wanted to use imagery that would convey the message the stories presented. Reading the oral history transcripts, I found lots of interesting details to include, like with the different types of food to include in the FEAST composition. It was inspiring to hear everyone’s unique voice sharing aspects about their and their family’s lives.

Q: How did you choose the various scenes and stories that you eventually depicted? What stories in the transcripts most stood out to you? Why?

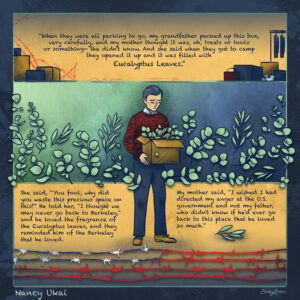

Emily Ehlen: I illustrate with the goal to portray a story the audience can connect and respond to. I wanted to choose stories with lots of emotions that I could highlight in each drawing. The piece I got the most emotional while drawing was Nancy Ukai’s grandfather in EUCALYPTUS. I sympathized with the longing and sadness of missing Berkeley that her grandfather felt. I understood the rationality behind using the box for something else, but that emphasized just how important Berkeley was to him. It was heartbreaking to read, so I knew I had to draw it.

Q: What are some of the story themes that you worked to express throughout your art for this project?

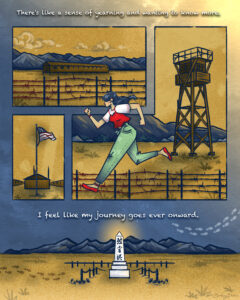

Emily Ehlen: The focus was how the Japanese American incarceration during World War II impacted themselves, their families, and how they responded to it. The themes were identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. I wanted the weight of the words to be carried through to the art accompanied with them.

Q: Can you describe some of the visual themes or repeated imagery that you incorporated throughout the various pieces you created? How and why did you develop these visual themes?

Emily Ehlen: The color palette I used helped create the tone and atmosphere of each piece separately while also keeping the collection cohesive. The red was used with duality: the bright saturated hue represented youth, rebelliousness, and intensity; while the dark maroon represented authority and repressed quietness. The soft green color was used to depict change and positivity that connects to the healing theme. The navy blue signifies unity and freedom, but it is used with a sense of serenity and heaviness. For example, the blue in TEACHER extrudes an overbearing presence in contrast to when it’s used in TREE. The ochre yellow has different meanings for its surroundings, like in TEACHER it signifies uncertainty, and in STORIES it’s used to display hope.

The water pattern, waves, and watercolor texture are used with family elements, and it contrasts the dry gritty spray paint texture that references the environment of Topaz and Manzanar. Waves are symbols of growth, renewal, and transformation. They also represent the unpredictability of life, to which people learn to navigate its ups and downs. The plants and paper cranes also relate to family connections, development, and healing, going through many stages and flourishing together.

For darker imagery, I wanted the red barbed wire to be synonymous with the red stripes we see on the American flag. To show the lack of freedom and injustice that the Japanese Americans faced, those stripes became wire that entrapped and left scars on following generations. The guard towers were a beacon of looming authority and danger at the incarceration camps. They became a mental block for some that were confined in their silences.

Q: While creating the JAIN art, what did you learn that was new to you?

Emily Ehlen: I really enjoyed learning about everyone’s perspectives and experiences with being Japanese American. I am Chinese American, so I empathize with the stories about identity and the sense of belonging. This project lit up my desire to discover more about my culture. My motivation for drawing is to see how my art mirrors my development as a person. I think art is a record of growth and change. Like time, it never stops moving forward.

Q: Can you describe one or two of your favorite pieces that you created for this project? Why does this one stand out for you?

Emily Ehlen: This is like asking the question, “Who’s your favorite child?” It’s super difficult because I love each piece for different reasons. I had the most fun drawing the piece SPLASH, about Jean Hibino and her mother. I think it has the most dynamic composition with how the imagery flows together with the text. I like the sequence of stillness to movement, and how a ripple can start a wave.

Q: What are your hopes for how people engage with your art for this project? Who do you hope sees it? What do you hope people take away from your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: My hope for how people engage with the comic is to have open conversations about them or topics related to it. It would be nice to see what sticks out to people the most and what connections they make through their perspectives. I hope people are able to feel the sentiments in each piece and learn new aspects of its history. I can’t think of anyone specific I’d want to see it, but I strive to be someone who inspires others by taking creative approaches to new ideas. So, I hope other artists who are interested in drawing and story-telling see it

You can see and save copies of larger images of the graphic art that Emily Ehlen created for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project in a separate blog post. We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.