by OHC Emeritus Historian/Interview Eleanor Herz Swent

An account of the creation of a modern, environmentally sensitive mine as told by the people who developed and worked it, from the University of Nevada Press Spring 2021 catalog.

In connection with this, Swent will be presenting her work as part of the American Society for Environmental History’s Environmental History Week. Her panel will be on Earth Day, and more information can be found here.

……………………………………………………………………………………..

As this was written, the Mars Rover Perseverance landed, thanks in part to research conducted at the mine in Napa County that was the subject of this book.

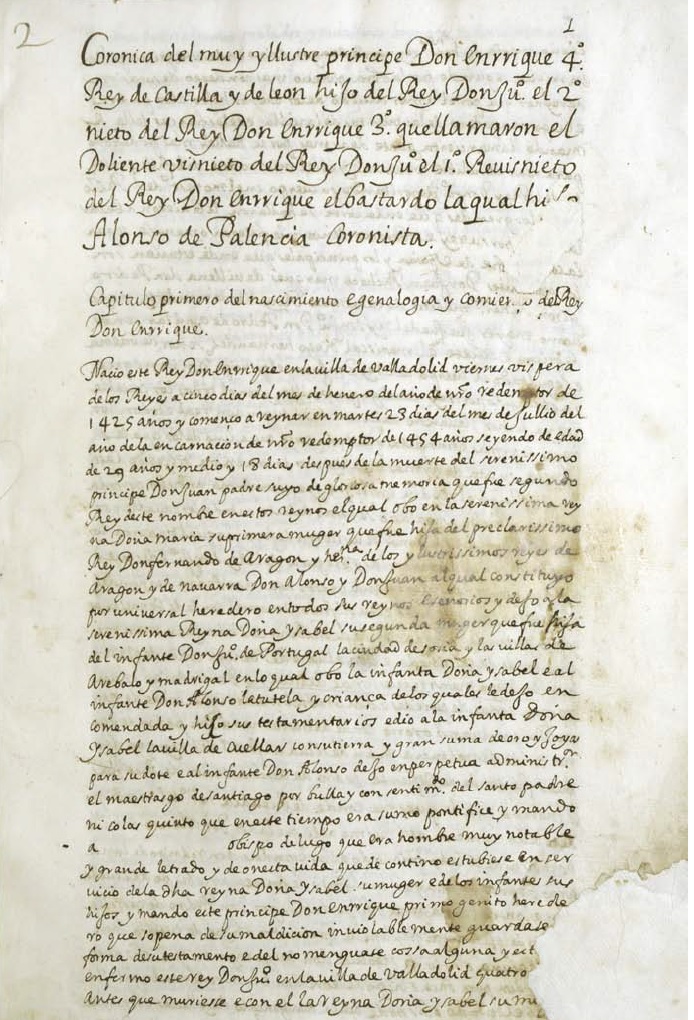

This is a different kind of oral history – not the life of a person, but of a mine – California’s most productive gold mine of the twentieth century. Between 1985 and 2002, the mine produced about 3.4 million ounces of gold, transforming the state’s poorest county and changing the industry around the world. OHC’s Knoxville/McLaughlin project, the basis for this book, comprised forty-eight interviews conducted over ten years.

In 1965, James William Wilder had a successful earth-moving and hauling business and decided to try mining. His research led him to buy the Manhattan mercury mine in the Knoxville District of Napa County. “We called it One Shot. If we don’t make it on this one, we’re out of the mining business.”

In 1974, Willa Baum, director of what is now the Oral History Center, was advisor for an Oakland neighborhood history project endowed by the NIH, and Eleanor “Lee” Swent was a volunteer, interviewing residents of the Fruitvale district and Chinatown. When Willa learned that Lee had spent most of her life living in mining towns, and that both her father and husband were mining engineers, it seemed that the time had finally come to document one of the most important aspects of California history – mining. In 1986, with the support of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers [AIME], the Mining Society of America [MSA], and the Woman’s Auxiliary to the AIME [WAAIME], the oral history series on Western Mining was established, and from then until 2001, Lee conducted 46 full-length oral histories with significant figures in the industry. They were men, with three exceptions: Helen Henshaw, the wife of the president of Homestake Mining Company; Catherine Campbell, geologist, editor, and widow of Ian Campbell, California State Geologist and Director of the California Division of Mines and Geology; and Marian Lane, aka Winnie Ruth Judd, wife of a mine doctor.

In 1978, a young geologist working for Homestake Mining Company, California’s oldest corporation, explored the One Shot mercury mine. “It was just a joy to look at. It has to be one of the best exposed, zoned gold deposits that ever was. It was just a type example of the mercury-hot-springs-gold association; a classic example.”

It was accessible only from Lake County, at that time, the poorest in the state, with a median household income of $5,266 and a population of 19, 548. By 1989, when the gold mine was in production, the income had about quadrupled, to $21,794, and in 1990 the population was 50,631. With funding support from Homestake, a community college branch was subsidized to train local workers, a hospital expanded its services, telephone and electric utility service was extended, and roads were paved. Many of these improvements were lasting benefits to the county.

The life of the mine was projected to be about twenty years, and most of the key players were available for interviews. It was a rare opportunity to document the discovery, development, and reclamation of a mine while it was happening. In 1991, the Knoxville District/McLaughlin Mine oral history project was launched.

Between then and 2005, forty-eight interviews, from two to seventeen hours long, were conducted with the owner of the One Shot Mine; Homestake officials and a wide range of employees; supervisors and planners from Napa, Lake, and Yolo counties; the Lake County school superintendent, local historians, mercury miners, merchants, and ranchers, as well as some of the most vocal opponents of the mine. Their voices help to tell the story of the mine and a changed community.

An engineer from New Zealand was manager for the construction. “This was the biggest nonunion construction project that had ever been done in California. It was thirty-odd miles long and we did 3 million man-hours. We engineered the dickens out of everything.” A rancher’s wife appreciated her job as a mine surveyor. ”I’ve learned invaluable stuff on the computers that I had never had any experience with before.”

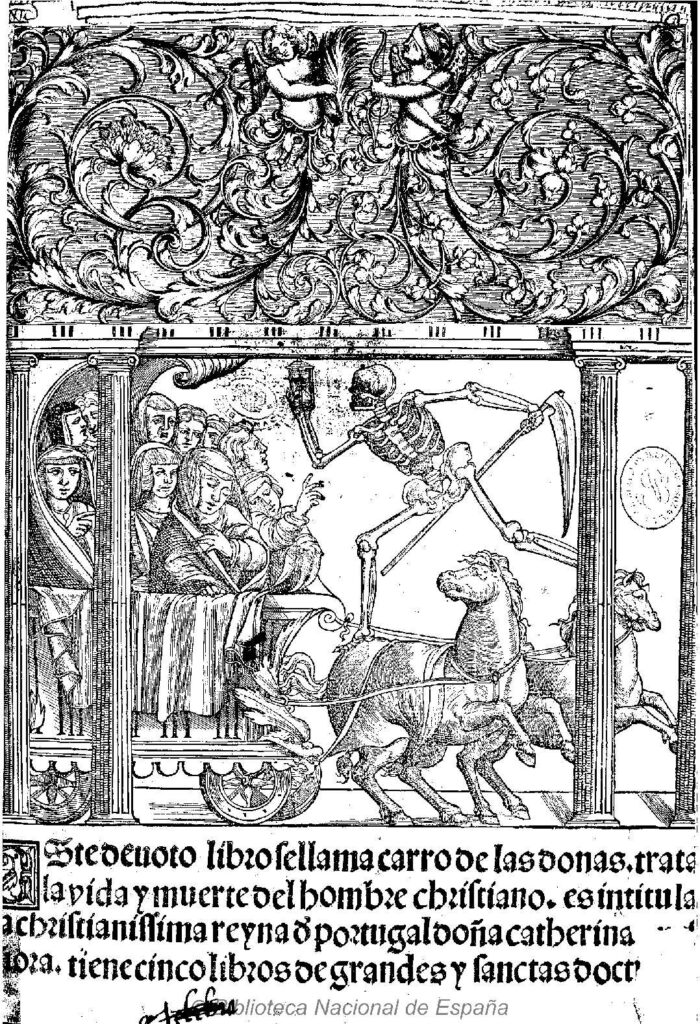

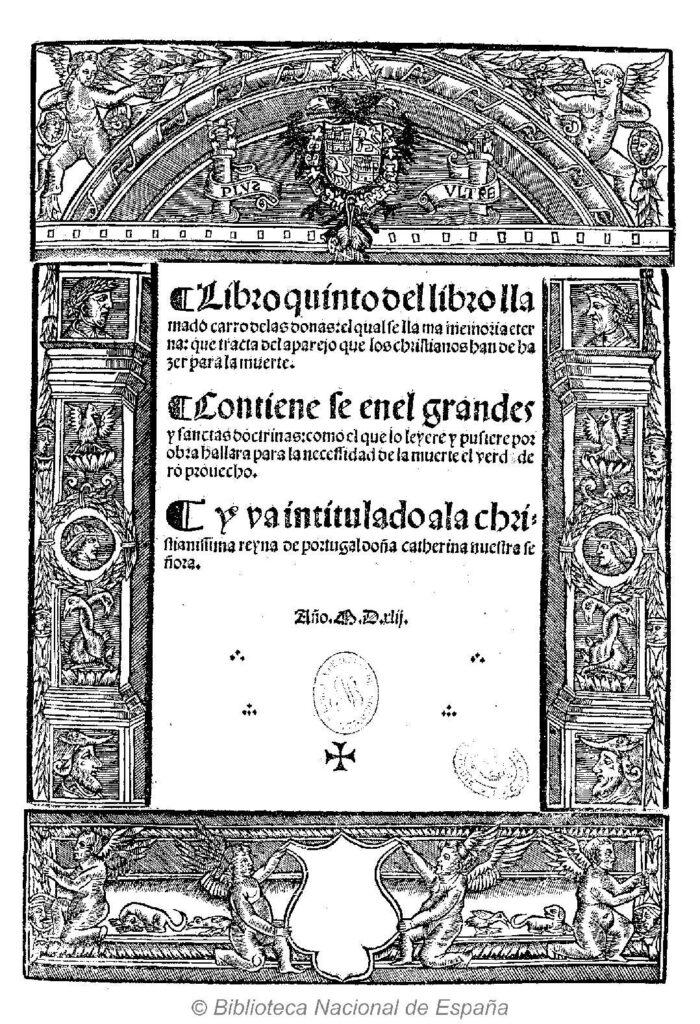

“One Shot for Gold” documents the effort to win public support and to obtain an unprecedented number of 327 permits from the federal, state, regional, and local agencies that had jurisdiction. Homestake engineers tell of their research from Finland to South Africa to develop the method of high-pressure oxidation to recover gold from ore without polluting air or water; it has now been copied around the world.

The mine was named for Donald Hamilton McLaughlin, chairman emeritus of Homestake and a regent of the University of California. In 1961, his wife, Sylvia Cranmer McLaughlin, founded Save San Francisco Bay, one of the first grassroots environmental organizations, that sparked national awareness and led to the first Earth Day, celebrated in San Francisco in 1974. This movement forced Homestake to incorporate environmental protection into its business model. From the beginning, plans for the mine included reclamation as the Donald and Sylvia Nature Reserve, part of the University of California Natural Reserve System. He died at the age of 93 on December 31, 1984, and Sylvia McLaughlin dedicated the mine to him in a ceremony on Saturday, September 28, 1985. The natural reserve named for them is a fitting coda to the story of a modern mine: extracting one precious resource, gold, and preserving another, the natural environment, its air and water.

In 2001, the mine geologist recalled, “NASA Ames research showed up at the door to look at samples of rock from our hot springs terraces that contained fossilized bacterial remains, evidence for the most primitive live on earth, to think through how landers on Mars would go about sampling and looking for evidence of life.”

“One Shot for Gold” begins with the mercury mine at Knoxville and ends with the Donald and Sylvia McLaughlin Nature Reserve. On February 11, 2021, the director of the reserve wrote, “Since around 2010, we’ve had a team from NASA and biogeochemists from various universities working on understanding the bacteria that live in geologic water deep inside serpentine rock, and how those studies can inform exobiologists where to look for life on other celestial bodies.”

As this was written, the astrobiology Rover Perseverance landed on Mars, ready to hunt for signs of life like those preserved at the depths of the Mclaughlin mine.