Tag: summer institute spotlight

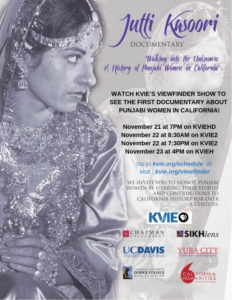

Cal Alum Makes PBS documentary on California’s Punjabi Community

OHC Advanced Oral History Alum Spotlight: A Q&A with Nicole Ranganath

Cal alum Nicole Ranganath’s documentary on California’s Punjabi community recently premiered on PBS. Currently an Assistant Adjunct Professor of Middle East/South Asia Studies at UC Davis, Ranganath joined the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at our annual Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2015. She was working on a project about women in California’s Punjabi community, and looking to deepen her interviewing skills. Since then, her project grew into a documentary film, Walking into the Unknown, which features 24 life stories of women from this community. We caught up with her to discuss her use of oral history, the film, working with students on the interviews, and why the time was right to do this project.

Q: You joined us in 2015 for the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. What initially brought you to the Summer Institute?

Raganath: As a Cal alum who worked at Bancroft library as an undergrad, I was already familiar with the great work at the Oral History Center. When I started planning my ambitious project documenting the history of California’s Punjabi community, I found the Summer Institute online and signed up!

Q: You were working on an oral history project about women in California’s Punjabi community. Tell us a little bit about the project.

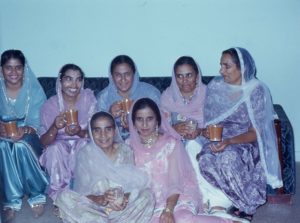

Raganath: This is the first documentary that focuses exclusively on the untold stories of women in the Punjabi American community of northern California over the last 110 years. Walking into the Unknown features interviews with Punjabi women from diverse backgrounds about their lives, including growing up in India, marriage and family, journeys to the US, and their professional careers. Their extensive contributions to the Punjabi American community and the broader American society have remained invisible. The women also offer compelling eyewitness accounts of major historical events, such as the 1947 Partition, in which over 14 million people were displaced and over one million murdered in religious violence. The project is funded by a grant from the California Humanities, as well as support from UC Davis, Sikhlens and the Punjabi-American community.

What made the project even more poignant is that there was a very narrow window of time in which we could give women a platform for sharing their life experiences. In December 2017, we completed 24 life history interviews on film in Yuba City, Sacramento, Davis, San Francisco, Fremont, and San Jose in just SIX DAYS! Over the last year, the health of three of the elderly ladies was declined so rapidly that they would no longer be able to be interviewed, and sadly one woman passed just away last month.

Q: What did you learn at the Summer Institute that helped you develop the project?

Raganath: The Summer Institute offered a holistic approach to thinking through and planning every aspect of my oral history research. Two aspects of the SI stood out — [OHC Director] Martin Meeker’s help thinking through the agreement process between UC Davis and the partner community organizations, and brainstorming with other participants about their projects. I learned so much from my colleagues.

Q: The project grew into a documentary, Walking Into the Unknown, which features in-depth life stories of 24 women that were interviewed. What was it like to turn these interviews into a film?

Raganath: When I embarked on the oral history research, I didn’t initially intend to create a documentary. With the tremendous support of Sikhlens and the Punjabi community, I got the courage to try to create a documentary film. I’m partnering with the UC History/Social Science Project to integrate the film into K-12 classrooms throughout the state. I encourage other oral history researchers to harness the power of the film medium to share these compelling stories with the general public. I’m very passionate about informing the general public about the Punjabi community’s presence in our state since the 1890s. Most people think South Asians arrived recently in California since the 1970s, but this vibrant community helped build our agriculture, our economy, our railroads, and have contributed to every aspect of our public life. For instance, Dalip Singh Saund was the first Asian American, the first Indian American, and the first Punjabi Sikh to be elected to the US Congress (1956).

Q: How did you adapt the interviews for film?

Raganath: One of the greatest pleasures of this project was creating a summer seminar with 10 students (mostly female Punjabi undergraduates at UC Davis), but also a masters student and a high school student. The students helped translate and transcribe the interviews and within one month they created 800 pages of single-spaced transcriptions of the interviews. We also met each week during the summer to discuss our responses to the often highly emotional interviews with the women. The student feedback greatly influenced my editing process. I was very concerned with capturing the diverse experiences of older pioneer women while also engaging young people to take interest in this history. Editing all of the footage to a short program that is 26 minutes and 43 seconds was not easy! I also greatly benefited from feedback from the other Punjabi women on the planning team who grew up in Yuba City and who were the daughters of some of the pioneer women interviewed in the film — Raji Tumber, Sharon Singh, and Davinder Deol. In short, the editing experience wasn’t easy but the community collaboration and engaging students in the process really helped. The editing team at Sikhlens, especially Hansjeet Duggal, was wonderful to work with as well. The KVIE team also provided invaluable feedback, including Michael Sanford, David Hosley and Alice Yu.

Q: The film premiered at Sikhlens Film Festival in LA in November. What was the reception? Did any of the audience members discuss the use of oral history?

Raganath: The reception at the Sikhlens Film Festival was incredibly positive. Nearly 40 community members, including one of the key pioneer women (Mrs Harbhajan Kaur Takher) attended the premiere. I brought the women involved in the project on stage to honor them. Mrs Takher received a standing ovation.

On November 21, 2018, Walking into the Unknown was broadcast on our local PBS station, KVIE, on their Viewfinder show. You can watch it at kvie.org/viewfinder. The program will rebroadcast on KVIE in April and will be uplinked to other PBS stations nationally later this year. There will be a community screening at the Yuba City Sikh Temple on Sunday, March 17 at 2 pm on Tierra Buena Road. The film will also be screened at the UC Davis South Asia Film Festival on Saturday, May 4 at the International House in Davis. It was very touching to see these courageous women get publicly acknowledged.

Q: What’s next for you? How do you hope to continue using oral history in your work?

Raganath: For this project, I’m finishing part two. We’re in the middle of creating a “women’s gallery” on the existing UC Davis Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive (pioneeringpunjabis.ucdavis.edu). These women’s stories, including video and audio clips, will be ready by June 2019 for anyone in the world to watch and enjoy. I’m also submitting an article about this project for publication. After that, I’m continuing my oral history work on a book about Sikhs who served in the British colonial administration in Punjab, Fiji, and Africa but then later settled in Yuba City, CA.

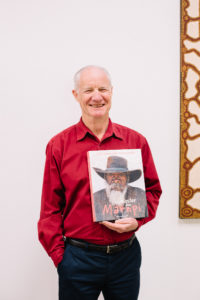

OHC Advanced Oral History Summer Institute Alumni Spotlight: Alec O’Halloran

We recently caught up with one of our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute alums, Alec O’Halloran, who recently published a book that was influenced by his work with us. His book, The Master from Marnpi, is based on oral history interviews. O’Halloran reflects on his work, his time with us, and the release on his book.

(Applications are open now for the 2019 Summer Institute from August 5-9. Apply now!)

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

I don’t have a ‘first’ recollection. I’ve always been interested in stories and in the 1990s (in my forties) I was drawn to the larger story of Aboriginal art and history in Australia, which I knew very little about. This led to reading autobiographies and biographies of Indigenous people, as well as attending art exhibitions etc. Oral history interviews were often quoted in stories about Aboriginal artists, particularly older people from remote parts of Australia that most of our population knew very little about.

When I began researching the life of an artist whose work I admired, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, I found out he had done two recorded interviews in his language, Pintupi, a decade before he passed away (1998). I found those interviews – or their translated transcriptions – fascinating! What a life he had led… so different to mine. Those interviews motivated me to look around for more oral history work that engaged with Aboriginal artists in particular.

Q: Tell us a little bit about the project you were working on when you attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute.

I attended the Institute in 2010, in part with support of a travel grant from my institution, The Australian National University in Canberra, where I was undertaking a doctoral program in Interdisciplinary Studies. My thesis project was the life and art of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. I had a rough draft of his life story by that stage, and I was mostly preoccupied with assembling the chronology of events, rather than comprehending his character.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

One thing I still remember from one of the guest lecturers was about ‘listening and hearing’ when working with recorded interviews. And with so many conversations with fellow participants about each other’s projects, I realised I was not fully engaging with the materials I had at hand. So, I when I returned home to Sydney I took a more rigorous approach.

I went back to the original recordings of Namarari (one audio, one video), and the transcripts, and tasked myself to see and hear more than I had before. To not only track events and incidents and the chronology of his life story, but to look beneath and between the lines and sounds for character and personality traits, for nuanced references to culture, to allusions to relationships with other people. I said to myself, ‘These two interviews are like gold, I need to use them to the fullest’. So the Institute motivated me to be much more dedicated to the oral history component of the biographical research about Namarari’s life and art. This certainly improved the quality of my writing when I was integrating Namarari’s voice into a wider story that involved multiple voices and archival sources.

Another outcome too. Oral history as a data-making history-creating method became more important to me. I don’t think I was an expert practitioner, so I tried to improve the quality of my interviewing work. This involved better planning of interviews and better conduct as the interviewer. Also, I saw that I had an opportunity to contribute to the field in a meaningful way.

The region where Namarari lived is called the Western Desert. It occupies a vast swathe of Central Australia. (Bigger than Texas!) My field work took me to that region, first by air to Alice Springs, and then by four-wheel drive (essential for the outback gravel roads). I realised I could do additional oral history work outside my specific research project as part of my travels. During 2011-13 I was awarded two oral history grants by the Northern Territory Government, which I applied to producing two community oral history reports: for the desert communities of Mount Liebig and Kintore. I interviewed some twenty Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and submitted a report, and deposited the interviews with the Northern Territory Archives Service in Darwin. I hope that one day a community member or researcher will come along who wants to write a local history of those places and find those interviews… they can then serve a good purpose. Importantly, but sadly, some of the people I interviewed have passed away.

Q: What’s the status of your project now?

My project, to produce an authorised biography on the life and art career of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, is complete! The master from Marnpi was released on 7 September 2018.

See my website for more information www.alecohalloran.com

Q: How did your biography, The Master from Marnpi, benefit from the use of oral history?

Namarari passed away in 1998, before I started my research, so I never met him and I could not interview him. This contrasts sharply with the majority of Aboriginal artist’s biographies in recent decades in Australia – they are invariably deep collaborations between the author and subject.

My narration of Namarari’s life story is based on his testimony: two interviews recorded in Pintupi, in 1989 and 1992, each conducted in the Western Desert by non-Aboriginal researchers who had travelled there for that purpose (and to interview other Aboriginal people of the area).

Thus it is his (translated and transcribed) voice that runs through the chapters. The many gaps are filled, where possible, with other oral history interviews I did with his relatives, and with art advisers who worked with him across his art career (1971-1998). I also drew on other oral histories, both my original interviews and from the archives, to enrich the narrative, applying more details to local histories of place, and shining a light on prevailing attitudes and circumstances that Namarari and his Aboriginal countrymen found themselves in. Where possible, I added salient photographs from a wide range of archives to illustrate what was referred to in the text by people who were ‘there at the time’.

Q: You have some visual components in the book, like maps. How did you weave visual elements with oral history?

The non-text items are: maps (of Australia, and the Western Desert region where Namarari lived), diagrams (eg, the Aboriginal kinship system), tables (eg, Namarari’s annual art output from 1971 to 1998), photographs of people, places (eg, desert scenes, Namarari’s house), and art (primarily his paintings).

The visual components serve to show the reader something of what the story-teller (eg, Namarari or his relatives) was talking about. If it was an important water-source location from his childhood in the 1930s, I would include a photograph. If it was a settlement where he lived in the 1950s, I would look for appropriate pictures from that era. Unsurprisingly there are many more useful photographs from the 1990s than the 1950s.

I applied a policy of sorts to the inclusion of images: it had to illuminate something in the text, rather than being a decorative piece to fill a space. I sometimes juxtaposed images to make a point, such as two artworks that had a subtle feature in common.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

I have really been preoccupied with my book for several years, so I haven’t been looking for extra inspiration. When I was doing the biographical research I drew inspiration (and understanding) from reading Indigenous autobiographies… they often had the raw truth of historical circumstance from the mouths of those who experienced events and situations and policies.