By Serena Ingalls

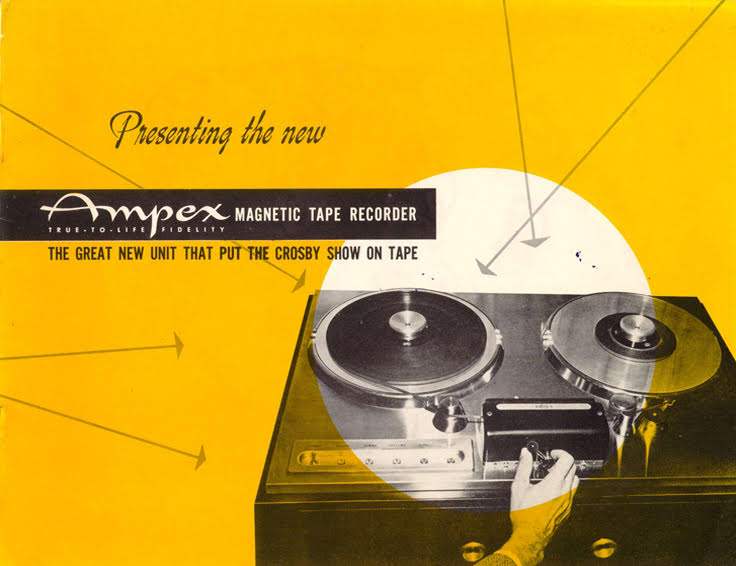

Seventy-five years ago, in April 1948, Ampex began to sell the first audio tape recorder commercially to the public, the Ampex Model 200. This product, a rather large and bulky unit, was first marketed towards local and regional radio broadcasters and promised to be well worth the cost due to its utility. As time went on, audio recording technology only became less expensive, smaller, and more widely available, notably with the creation of the cassette tape by Philips. The invention of audio tape recorders made a huge mark on the world, and it impacted the daily lives of many, particularly those who spent much of their time interviewing and taking notes. In the archive of the UC Berkeley Oral History Center, there are many casual mentions of tape recorders that reveal the importance of these devices, and how people thought about and experienced the recording of interviews.

Sports journalist and UC Berkeley alum Glenn Dickey began his career before tape recorders were generally used in the field, so he became very skilled at taking shorthand notes. His ability to take notes and remember conversations verbatim was so remarkable that others doubted that he didn’t use a tape recorder. In his oral history, Dickey talks about tape recorders and reflects on a personal experience. “One time when Garry St. Jean was an assistant coach for Don Nelson, he had a bet with Don Nelson that I have a tape recorder hidden,” explained Dickey. “Because he’d be there when I was talking to Nelson, and he knew that what I was writing in the column was what Nelson said—he says, ‘He can’t remember all that.’”

“It is easy to say now that I can narrate the story of my life on a tape recorder before writing these memoirs down, but for millennia it was impossible and everything hinged upon the spoken word, and all traditions and all the knowledge gradually accumulated by humanity depended upon this knowledge.” — Alexander Paul Albov

Others took full advantage of the tape recorder as a memory aid. Jo DeJean, the personal assistant to Gary Rogers at the Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream Company, was one such person. She recalls in her oral history that “on my ride home I would talk into a tape recorder about things that I needed to do. We didn’t have cell phones back then. Because I had all these things swimming around in my head, so I needed to record them. So that’s what I did.” This strategy is now employed by many through the means of “voice memo” features on smartphones.

When tape recorders became inexpensive and easily accessible, they were used consistently by interviewers. Tape recorders were incredibly useful tools for longer interviews. Sometimes during the oral histories conducted by the Oral History Center, the methodology of the interviewers makes its way onto the record through the mention of tape recorders and other tools.

One interviewee, George W. Waters, former editor of Pacific Horticulture, became curious about the tape while his interview was being conducted. While chatting about interviewing techniques, Waters asked about what would become of the tape after the interview was done, and the interviewer, Suzanne Riess, replied “You can ask that the tape be destroyed, if you really wish.” This remark seemed to surprise Waters, and he replied, “Well, I appreciate the fact that somebody else has accepted the job of transcribing it. No, there are advantages and disadvantages [to using the tape recorder], and well, I wouldn’t have missed this for the world. It’s so rare, isn’t it, that one gets an opportunity to talk about himself to someone who’s actually interested in staying?”

Sometimes, however, the presence of a tape recorder could create an awkward barrier between the interviewer and interviewee. Robert D. Harlan, professor of the UC Berkeley School of Librarianship (later the UC Berkeley School of Information), who also conducted oral history interviews for the Oral History Center (then the Regional Oral History Office), was asked about his experience in his own oral history. Harlan reflects that “Having been both the interviewer and the interviewee, it’s easier to be the interviewee, I think. It’s more reactive. You know, I don’t have to change the tapes and that sort of thing. [laughter]” At the same time, he recalls that one of his interviewees had difficulty in opening up because “he found the process intimidating, sticking this thing [tape recorder] in front of him, so I had to work at it. And well, you’re certainly aware of this. It can be a problem. I wish he’d been a little more forthcoming.”

Even if they sometimes initially hindered the flow of conversation between the interviewer and the interviewee, tape recorders and more modern recording devices are invaluable to the creation of oral histories. They allow for relaxed conversations that can be transcribed at a later date by someone who wasn’t present at the original interview. Recording devices and the transcripts that are produced are more accurate than one’s memory and shorthand notes as well.

More than anything, these recording devices allow us to do what we’ve always done: pass down stories of one generation to the next. Today, the Oral History Center not only records their words, but we also record videos of the narrators. This allows us to capture the sound, rhythm, and accent of someone’s voice, which will make a new viewer of an oral history video feel as though the story is being told to them directly. Although the transcripts usually contain photos of the narrator, the additional video content shows the person in motion and the nuances of their expressions. The combination of oral history transcripts and video recordings, only possible now due to advancements in technology since the first tape recording device, preserves the stories of those in our past and present for future generations. Like a fossil preserved in amber, these histories are immaculately preserved, but rather than being a gift from nature, the preservation of oral histories is a product of evolving technology — and the extensive work of all of the interviewers, transcribers, and professional and student staff of the Oral History Center.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

Serena Ingalls is a fourth year student in History and French at the University of California, Berkeley. She works at the Oral History Center as a research and editorial assistant.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

For sources related to athletics, see the Oral History Center’s project, Athletics at UC Berkeley. The Bancroft Library also holds several books written by Glenn Dickey, including Glenn Dickey’s 49ers : the rise, fall, and rebirth of the NFL’s greatest dynasty ; Bancroft (NRLF) ; GV956.S3 D518 2000.

For sources related to Dreyer’s ice cream, see the Oral History Center’s projects, Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream; Food and Agriculture — Individual Interviews; and Commerce, Industry, and Labor — Individual Interviews. See also: Dreyers: history in the making. Bancroft Pamphlet Folio ; pf HD9281.U54 D7 1997.

For sources related to horticulture, see the Oral History Center’s project, Natural Resources, Land Use and Environment — Individual Interviews. See also: California’s horticultural statutes with court decisions and legal opinions relating thereto, also county ordinances relating to horticulture and list of state and county horticultural officers corrected to March 1, 1908. Bancroft ; F862.21.C2.1908. Read the Oral History Center article, “U.S. Forest Service, California Water History, and Horticulturalists in the Natural Resources, Land Use, and Environment Oral History Project,” by Ricky J. Noel.

For sources related to University History, see the Oral History Center project, Education and University of California — Individual Interviews. See also: Robert D. Harlan papers, 1947-2000. BANC MSS 2003/225 c.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.