Author: pburnett

From the Oral History Center Director — July 2021

From the Oral History Center Director — July 2021

I recently had the pleasure of watching a new documentary film, The Sparks Brothers (2021), which details the solidly unconventional musical career of Ron and Russell Mael, lifetime stalwarts of the band Sparks. This film has everything one might want from a rock and roll documentary: rare footage of live performances, insightful commentary from artists influenced by the band (Beck, Bjork, Weird Al), and a narrative charting several artistic ups and downs. You might watch it and think that you caught an episode of “Behind the Music” (without the cliche visits to Betty Ford) or This is Spinal Tap (the new wave remix). But the thing about this film that really caught my attention — and got me thinking about our work at OHC — is how revealing and edifying a full life history can be (as is done with The Sparks Brothers as well as with many of our oral histories).

Growing up in California in the early 1980s, Sparks originally came to me as another hip, ironic, proudly nerdy Los Angeles new wave band. Surely the first song of theirs I heard was “Cool Places,” an absurdly upbeat synthpop song performed with and co-written by Jane Weidlin of the Go-Go’s. I saved my pennies and soon purchased the album (Sparks in Outer Space) and loved most every song. I followed their career through another few albums then, as teenagers do, moved on to other bands and sounds. To me Sparks remained in my memory as a genre-band — a very good one, but still one of a particular type.

Watching this full-life documentary, however, upset my own memories of this band. It revealed parts of their lives (including telling moments of their childhood) that were unknown to me. It showcased their early years as a Zappa-like freak band, their move to England where they earned fans as glam-rockers, their burgeoning interest in synthesizers and ultimately their collaboration with synth-god Giorgio Moroder, and finally their return to Los Angeles and reincarnation as a new wave band. The film also details the years since the 1980s, which took the pair in even more esoteric musical directions while continuing to win new fans, garner critical accolades, and stage frankly amazing artistic achievements. After watching this video, I am now eager to dig deeper into their music and thus discover bits of pop music past that thus far had been hidden to me. New music need not emanate from this day and age after all.

This is one of the reasons that I think the life history interviews we do at the Oral History Center are so incredibly valuable. When we conduct this type of oral history (ten hours or more with a single individual) we not only have the opportunity to ask the obvious questions (“tell me about the research that led to your Nobel Prize?” “What was it like to win at the Supreme Court?”), we are afforded the freedom to explore the lesser known aspects of a narrator’s life. With the additional hours of interviewing, we can document the narrator’s family background, upbringing, and education. We can detail early career moves that maybe didn’t amount to much but which taught crucial life lessons. We can document failures as well as successes. In my interview with Herb Donaldson, the first gay man appointed as a judge in California, I also learned about his side job as a coffee importer and roaster who gave key advice to a certain coffee shop getting started in Seattle (yes, Starbucks). With former Kaiser Permanente CEO George Halvorson, I got a fascinating account of his establishing a new health system in rural Uganda. And in my in-progress interview with famed Newsweek and Vanity Fair reporter Maureen Orth, there’s a lengthy description of her two years in the Peace Corps. While perhaps not what these people are best known for, these “other projects” not only provide great insight into the individual but often offer useful insights into historical events. Sometimes you think you know the whole story, or at least the most important part of that story. But when you read — or conduct — life history interviews, you soon learn that all parts are important and those less regarded can be the most surprising.

In this spirit of uncovering less known accomplishments, I want to pay tribute to Bancroft staff who recently retired. At the end of June we witnessed the departures of Bancroft Director Elaine Tennant (also a renowned scholar of German literature and culture), Deputy Director Peter Hanff (also a recognized expert in all things Wizard of Oz, which he detailed in his oral history), finance manager Meilin Huang (also the savior of the Oral History Center on many occasions), and photographic curator Jack von Euw (also an excellent curator of many Bancroft exhibits). We bid farewell to these four esteemed colleagues. We hope that retirement adds several new and interesting chapters to already very accomplished lives.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center

New Oral History: “Bruce N. Ames: The Marriage of Biochemistry and Genetics at Caltech, the NIH, UC Berkeley, and CHORI, 1954–2018”

I realize that the title of this new oral history, “Bruce N. Ames: The Marriage of Biochemistry and Genetics at Caltech, the NIH, UC Berkeley, and CHORI, 1954–2018,” can give the impression of a sequence of institutional histories framed by the life of one researcher; it’s really more about a certain type of scientific inquiry that manifests itself as a career that is both varied and foundational to the work done at each of these places. Dr. Ames studied with H.K. Mitchell at the California Institute of Technology at the beginning of the revolution in molecular biology, which was the coming together of genetics, or the study of inheritance and development, and biochemistry, or the study of the chemical processes that underlie cellular processes. A key part of this revolution of course is the discovery of the helical structure of DNA by James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Francis Crick at Cambridge University. But to boil it all down, it became possible to see biochemical processes functioning not only as reactions to changing environments but also as the expressions of a genetic code that could be “switched on” or repressed experimentally. At Caltech, Ames displayed the kind of curiosity that endeared him to scientists like Max Delbrück, whose “phage group” was beginning to look at these biochemical mechanisms of genetics.

There was just a handful of sites in the early 1950s where this new work was being undertaken. Although Ames did his graduate training in biochemistry, he was always “hopping the fence” to look at what was going on in other disciplines, especially genetics. He joined the National Institutes of Health in 1953 as a fellow, and rose to become the Chief of the Microbial Genetics section in 1962. During his time at the NIH, Ames split a fellowship year at Crick’s laboratory at Cambridge and another at Francois Jacob and Jacques Monod’s laboratory at the Pasteur Institute. Historians of science have recorded their suspicions of some of these famous scientists, who learned of Ames’ idea that the biosynthetic pathways of histidine were achieved through the activation of several coordinated genes, which led to Jacob and Monod’s theory of the operon—which is a cluster of genes expressed by a common promoter—without attribution to Ames. Asked about it decades later, Ames seemed surprised that historians of science had documented this observation. But these research programs in which Ames participated laid the foundations of the molecular understanding of life: in 1961, Sydney Brenner (Crick Laboratory) and Monod published the discovery of messenger RNA, or mRNA—a copy of DNA that initiates cellular processes—which is the foundation of the new vaccines developed to protect against COVID-19.

What becomes apparent reading Bruce Ames’ oral history is that he himself functioned as a kind of synthesizer. A restless mind began a research track, produced results, but then became distracted by an active curiosity with respect to research in other areas of biology, or even in social sciences or political philosophy. In the labs he ran at NIH, UC Berkeley, or the Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute, Ames generated interest among colleagues, post-docs, technicians, graduate students—even among undergraduate students or amateur activists—to undertake research in a new direction. Once the program was off the ground, Ames was often already thinking about new areas of research.

Such was not always an easy path, as the expected institutional rigidity and disciplinary boundaries sometimes made for cool receptions when Ames attempted to enter a new field. In the mid-1960s, just before he moved from the NIH to take up a professorship in biochemistry at UC Berkeley, Ames became interested in the chemical preservatives in potato chips. This was the beginning of a long research trajectory in genetic toxicology, or the impact of toxins on DNA, at a time when the relationship between DNA damage and diseases such as cancer was poorly understood. Out of this research, Ames developed a simple inexpensive bacterial test for the mutagenicity of chemical substances, what became known as the Ames Test, which cut dramatically the time and money it took to determine the degree to which chemicals caused cancer using the standard method, animal trials. In the wake of this success, Ames was also frustrated by what he saw as the institutional inertia and the misunderstanding of critics of science and industry. To advocate for a more balanced view of modernity, Ames applied his test to the plants humans eat every day, and found mutagenic chemicals that are produced by the plants themselves in far higher doses than the trace amounts of pesticide residues that accompany them.

In 2000, Ames retired from UC Berkeley and became a senior research scientist at the Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute until his retirement in 2018. During this time, Ames followed the logic of his inquiries into plant toxicity to examine nutrition, specifically the micronutrients that protect our DNA from these mutagenic chemicals or processes. He then embarked on a third career — or fourth or fifth, depending on what we count — of research on micronutrients. With over 550 publications, he is among the top hundred most highly cited scientists across all disciplines. But perhaps more interesting than the story of a peripatetic and pioneering mind is Ames’ frequently proclaimed reliance on the talents of other researchers and technicians, whose widely varying backgrounds and skills, including those of his wife and fellow UC Berkeley scientist Giovanna Ferro-Luzzi Ames, complemented his talents and made the research possible. From oral histories of top scientists, we can easily conclude that science is about leadership, but the skill of leadership is revealed over and over to be the identification, nurturing, and coordination of diverse talents. That will surely be another of Dr. Ames’ lasting contributions to science.

From the Oral History Center Director: February 2021

From the Oral History Center Director

At the Oral History Center, spring begins in mid-January. Usually for OHC staff this means longer lines for morning coffee and scarce parking spots becoming rarer still. While we’re not experiencing these early signs of spring in 2021, we are looking forward to another early seasonal ritual: our annual Introduction to Oral History Workshop.

This year the workshop will differ from those we’ve hosted in the past in two key ways: it will be hosted remotely, so that we remain safely socially-distanced with the added benefit of making is accessible to those who don’t live nearby; the second difference is that it will be held over two days (Friday March 5 and Saturday March 6) to better accommodate those who are in not in the same time zone as Berkeley.

In addition to the slight changes in format this year, OHC faculty will focus more on the practice of remote interviewing. When the pandemic struck about this time last year, we put a hold on our almost-always-in-person oral histories and dedicated ourselves to a study of how we might conduct our interviews remotely while still establishing good rapport with narrators and capturing quality audio and video in our recordings. By August we optimistically put our toes back in the oral history waters by recommencing with our interviews. We’ve learned a great deal in the six plus months (and suffered no major tragedies) so we’re eager to share what we’ve discovered. Although we are all looking forward to the day when in-person interviews are once again the norm, we also recognize that remote interviewing now has a place in our work going forward — and we suspect you’ll want to know about this practice.

Registration is now open for the Introductory Workshop as well as for the Advanced Oral History Institute, held every August. We look forward to seeing you (virtually!) and together pursuing oral history in this strange new world.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director

From the OHC Director: December 2020

From the Oral History Center Director, December 2020

Resilience is one of those words that the Transcendentalists would Capitalize — and I’m good with that. Oxford Languages (which publishes the multi-volume Oxford English Dictionary) offers two main definitions of Resilience:

- the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness and

- the ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity.

Strength and flexibility. Google analytics has an interesting tool that proposes to show the prevalence of word use over the centuries. For “Resilience” it finds notable upsurges in the Great Depression, in the wake of 9/11, and the 2008 financial crisis. It’s a word we turn to with aspiration in difficult times. I’ll bet that we’ll see a marked increase in 2020, this difficult year of years, with a global pandemic, unrest in the streets, and a nation starkly divided.

While the word is often used in an aspirational way, to motivate and inspire, when I use it here, it is a fair and accurate description for the perspective and work of the remarkable staff and student employees of the Oral History Center in 2020. The year began with optimism but also challenges — we knew we had our work cut out for us with a large docket of projects to complete alongside the ever-present pressure of being a self-funding research program. Then, by late January, ominous clouds appeared on the horizon and we soon learned that vigorous hand-washing wasn’t going to stop the approaching storm. Not knowing if we’d return to the office in two weeks or … two years … we moved our operations online and became familiar with Zoom — as did most of the world. I’ll admit that those first weeks were difficult, rife with uncertainty and worry, so our virtual staff meetings focused on simply checking in with one another. And I remain thankful for having a group of smart, concerned, and level-headed colleagues to converse with in those early days of isolation. They made that time bearable and helped give me direction as head of the office. Notably, I recognized their Resilience and their readiness to continue to do the work that they are so passionate about.

While the word is often used in an aspirational way, to motivate and inspire, when I use it here, it is a fair and accurate description for the perspective and work of the remarkable staff and student employees of the Oral History Center in 2020. The year began with optimism but also challenges — we knew we had our work cut out for us with a large docket of projects to complete alongside the ever-present pressure of being a self-funding research program. Then, by late January, ominous clouds appeared on the horizon and we soon learned that vigorous hand-washing wasn’t going to stop the approaching storm. Not knowing if we’d return to the office in two weeks or … two years … we moved our operations online and became familiar with Zoom — as did most of the world. I’ll admit that those first weeks were difficult, rife with uncertainty and worry, so our virtual staff meetings focused on simply checking in with one another. And I remain thankful for having a group of smart, concerned, and level-headed colleagues to converse with in those early days of isolation. They made that time bearable and helped give me direction as head of the office. Notably, I recognized their Resilience and their readiness to continue to do the work that they are so passionate about.

When it became clear that we weren’t returning to the office anytime soon but that we weren’t quite ready to conduct oral histories virtually (something we always advised against “if at all possible” when we teach best practices), we turned our attention to other important tasks. Shanna Farrell, Amanda Tewes, and Roger Eardley-Pryor each contributed to our ad hoc podcast season, “Coronavirus Relief,” which was less about documenting the virus than about ways in which we were seeking relief from the emotional toll of it. Amanda and Roger, working with stellar Berkeley undergrad Miranda Jiang, completed a project begun pre-pandemic and released the excellent podcast/performance piece, “Rice All the Time.”

The Oral History Center is perhaps a more complex operation than might be apparent from the outside. A massive amount of work goes into the creation of the oral history interviews that you read and/or view on our website. There is of course project development, research, and videography, but there is also managing the complex process of creating, editing, and preparing transcripts that often run several hundred pages and can include forewords, photographs, and multiple appendices. In essence, we’re a small press publishing house that produces all original content. Two years ago we began the process of redesigning and then documenting this back-end operation and that process not only continued but accelerated during the course of this work-from-home year. Communications Manager Jill Schlessinger, with an eye for detail and keen awareness of what needs to be done, helped build this structure, drew up its plans, and then made it work by implementing a new online project management software solution. Likewise, Office Manager David Dunham contributed documentation of the technical side of our work (creating new transcript templates, digitizing analog recordings, writing metadata, etc.) during this time; moreover, he innovated by finding work-arounds for tasks usually done in person that now had to be done remotely. This behind the scenes work is plainly evident in this newsletter, with its abundance of newly released oral histories, completed with the necessary aid of this process during the pandemic.

As it became clear that in-person meetings would largely be prohibited for the foreseeable future, we adopted the spirit of flexibility and resolved to bring the operation fully online and conduct interviews remotely. Paul Burnett and Roger spent many hours studying and testing various options and came up with a workable solution — Paul even hosted an online tutorial which was attended by hundreds and is now available online. We began conducting remote interviews in August and have conducted close to 200 hours of recordings already! If that doesn’t indicate Resilience, I don’t know what does. As one of those interviewers who has benefited from Paul’s research, I can attest that it works; while remote interviewing isn’t the same as in-person interviews, I’ve learned it is still possible to gain a similar sense of familiarity and intimacy as in person. Even more important: all of these essential stories are getting preserved, the importance of this is glaring in the face of the fact that well more than 300,000 Americans will have died of this dreaded virus by year’s end.

The above is clear evidence of the Resilience of the remarkable staff and student employees of the Oral History Center but it doesn’t end there, not by a long shot. Rather than let their student employees go unemployed, David and Jill have devoted many hours to keeping them busy doing important tasks and allowing them to maintain their income. Todd Holmes, returning to the office in July after caring for his wife who sadly passed away, has finished up a number of outstanding projects, including the oral history of Chicano/a Studies and a set interviews with and about esteemed Yale scholar James C. Scott. Shanna was determined to forge ahead with our annual Advanced Oral History Summer Institute, changed by its virtuality but also by the fact that we had a record number of applicants and attendees. Amanda launched the new Women in Politics Oral History Project with a well-attended online panel discussion that featured Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, former SF City Attorney Louise Renne, and Pittsburgh City Councilmember Shanelle Scales-Preston. Paul with Jill’s considerable assistance launched our new educational resources pages (a space you’ll want to watch for exciting developments in 2021). Jill kept our communications program running and robust and thus helped spread word of this great work far and wide. We submitted three major grant applications (fingers crossed!). And, last but not least, Shanna kept this newsletter going with several content-packed releases.

When we look back at 2020 and see that almost predictable upsurge in the frequency of “Resilience,” I’ll know that this word is not only an apt descriptor — toughness and flexibility — for people’s aspirations during difficult times but also an accurate description of how we persevered and rose above to achieve something of real value. Finally, I want to offer my profuse gratitude to our many friends, sponsors, and partners and to Amanda, David, Jill, Paul, Roger, Shanna, and Todd, for making 2020 truly a story of Resilience.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

Read more about what we’ve been doing, listen to our podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Oral History Center Staff’s Top Moments of 2020

Podcast Season: Coronavirus Relief

Remote Interviewing Tips and Tutorial

Women in Politics Panel Discussion

Educational Resources: AIDS and Epidemics Curriculum

The Price of Place: Oral Histories of George S. Tolley and Howard R. Tolley

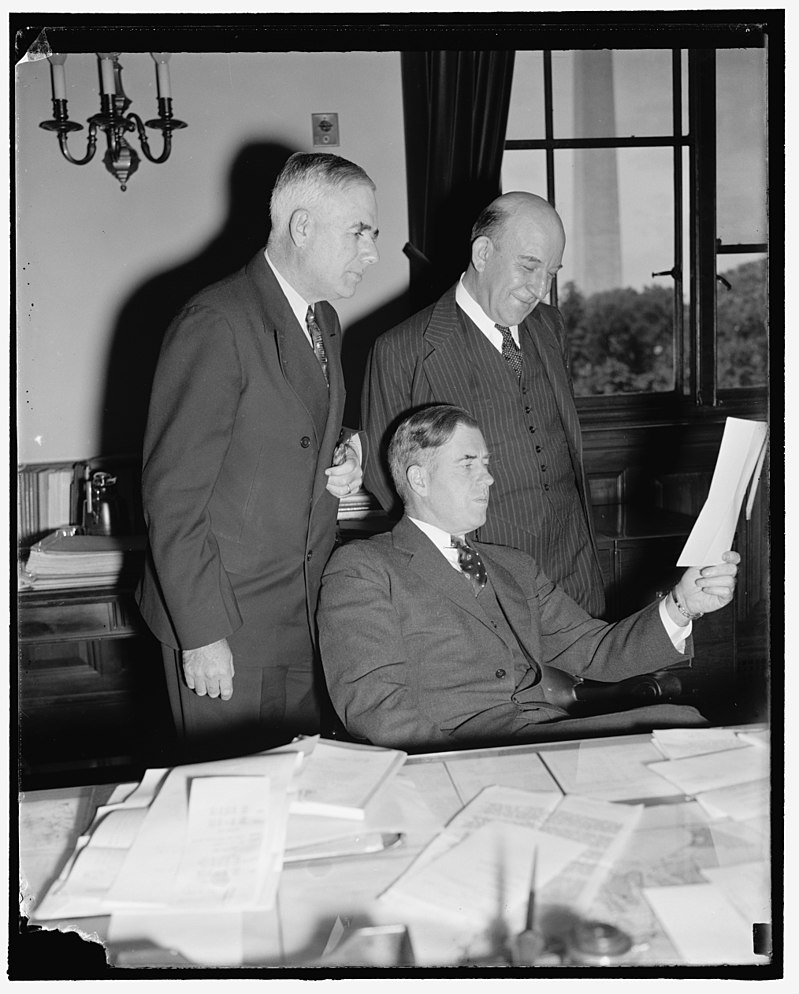

This interview with University of Chicago economist George S. Tolley is the latest in our series of interviews with Chicago economists as part of the Economist Life Stories project. However, along with this twenty-hour interview, we are also releasing online for the first time the oral history with his father, Howard R. Tolley, first head of UC Berkeley’s Giannini Foundation, and chief of the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (USDA) during the New Deal and World War II. This interview, conducted by Dean Albertson in the early 1950s, comes to us from the archives of the Columbia Oral History Project, which graciously granted permission for us to publish these interviews together.

Photo courtesy of https://www.wikiwand.com/en/M._L._Wilson

These interviews will be of enormous importance to historians who are interested in the social and political contexts of the social sciences. Economists at the University of Chicago have been deeply involved in policy advocacy and policymaking since the beginning of World War II. Growing up in Washington during the Great Depression, with a father who was responsible for analyzing and providing solutions to Depression-era farming, George S. Tolley felt that economics was the calling of his generation: to figure out how to prevent such a calamity from ever happening again.

George completed his PhD at the University of Chicago with Theodore Schultz and D. Gale Johnson in the 1950s, and returned as faculty in the 1960s. Schultz was the impresario for the department during this period, bringing his ethic of service to the nation, along with many important contacts. G.S. Tolley was part of Schultz’s agriculture group at Chicago, in which many prominent economists researched problems of agricultural modernization, whether in the rural US or around the world. True to this spirit of service, Tolley became the Director of the Economic Development Division of the Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture in 1964-65, and in 1974–75, he served as Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Office of Tax Analysis of the US Department of the Treasury.

As an outgrowth of his research on resource use and farm labor migration, G.S. Tolley was in on the ground floor of two new research areas, urban economics and environmental economics, neither of which could be more topical today. He also consulted widely for federal, state, and municipal agencies on urban and environmental problems from the 1960s until the present day, both as an academic and in his capacity as CEO of his firm RCF Consulting, Inc. As agricultural economics became central to policymaking in developing countries, so too did urban economics, as megacities mushroomed across the globe, echoing the influence of the agriculture group in this domain. In the late 1980s and 90s, George also produced a seminal work on health economics, which moved the field to a broader view of the economics of wellness.

Social sciences emerged to identify, define, and address the social problems and challenges of the age of which they were a part. If we think of the ideal of science as a belief in the possibility of making knowledge that stands independently of the biases, instrumentation, and idiosyncrasies of observation and experiment, we can understand what the social scientist is up against. Notwithstanding the commitments of many social scientists to such an ideal, it’s impossible for them to escape the social context in which they operate. Both of these oral histories chronicle policy controversies and challenges, and the emergence and evolution of sub-disciplines to tackle particular social problems (low farm income, labor migration, housing inequality and urban sprawl, management of natural resources, or the management of an insurance-based health care system). And both economists focused on the economics of human geography, the price of proximity to markets, opportunities, amenities, and resources. But the larger pattern in both life histories is this: the higher the political stakes of an area of research, the greater the social scientist’s commitment to an ideal of value-free science, often out of sheer necessity. George S. Tolley’s basic approach in his career was humility before the complexity of economic and social phenomena. But that approach becomes a policy orientation in itself: careful analysis of blanket prescriptions or proscriptions, and an understanding of the unintended consequences of well-intentioned plans, an orientation he passed on to his many accomplished graduate students.

From the OHC Director: October 2020

While we are in the midst of a year without precedent, I am lucky enough to be able to draw upon any number of well worn cliches to describe the current state of the Oral History Center: we’re running on all cylinders, chugging along, moving full steam ahead, and, happily, derailed no more. In this month’s newsletter you’ll see very clear evidence of the work that was accomplished during the months of shelter-in-place: the completion of many long-in-progress oral histories, our first remotely conducted Advanced Oral History Institute, and several other productive initiatives.

We have also moved well beyond the “wrapping up old projects” phase of 2020 and have forged ahead boldly by resuming our core activity of conducting new oral history interviews. Since I last wrote a newsletter column, the OHC team of interviewers has conducted oral histories for our projects with the Getty Trust, East Bay Regional Park District, Sierra Club, and San Francisco Opera—and we’ve done new interviews for our Chicano/a Studies and Women in Politics projects. History cannot wait and we’ve resolved to make progress in spite of the obvious limitations of this strange historical context. As always, we welcome ideas, feedback, and support.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center

New oral history – John Prausnitz: Chemical Engineering at UC Berkeley, 1955–2020

When I asked John Prausnitz about his interest in science growing up, he said “I really recognized that chemistry is life. Chemistry is how we live, and the body, what we eat, and what we inhale. Chemistry is it.” This is one key to understanding John Prausnitz’s approach to science and to life. He doesn’t separate them. His intellectual pursuits are not narrow. Although less and less so, engineering can still be understood as “mere” applied science, a question of fitting the fundamental principles long ago worked out by pioneering scientists to industrial or commercial processes. If this supposition was ever true, it really began to come apart around the time that Dr. Prausnitz entered the field of chemical engineering in the 1950s. And while he faced a brief moment when a possibility of a career in the private sector was presented to him, he quickly chose instead to devote his entire career and the rest of his life to UC Berkeley.

The mind of Dr. Prausnitz works on at least two tracks. First, he considers the challenges beyond the confines of the academy; but he also ranges widely over scientific and humanities literatures for tools to help him to interpret and solve these problems. He was a key mover in the foundation of the field of molecular thermodynamics: using the principles of molecular behavior worked out in physical chemistry to predict properties and behavior of mixtures of substances in various states. The scope of this revolution in engineering is hard to grasp until one considers the fact that many large-scale chemical processing factories were designed, constructed, and operated without careful consideration of chemical behavior at the molecular level. Some of his models that simplified the interactions of types of molecules were adopted by entire industries and would dramatically improve their efficiency and efficacy over the decades.

By immersing himself in the literatures of different scientific disciplines, Prausnitz attacked problems with a much broader perspective than if he had stayed in his field, respecting the boundaries of disciplines. Over the decades, Dr. Prausnitz has also been a witness to the expansion of the field of chemical engineering, from petroleum production processes to electro-chemical engineering to bioengineering. Prausnitz was not merely a champion on the sidelines of these new subfields; he immersed himself, quite late in his career, in molecular biology in order to collaborate on contributions to bioengineering, drawing especially on work with the Department of Energy in its sponsorship of biofuels research. Again, Prausnitz brought to bear his expertise in molecular thermodynamics to help place the research on a stronger footing.

Always, however, Dr. Prausnitz was thinking about the larger context and meaning of the work, and as an academic, this meaning had a lot to do with teaching and students. Like all great mentors, he took an active role in the progress and wellbeing of students and collaborators. As an enthusiast of the history of science, he understands that science is above all a human endeavor and a social process.

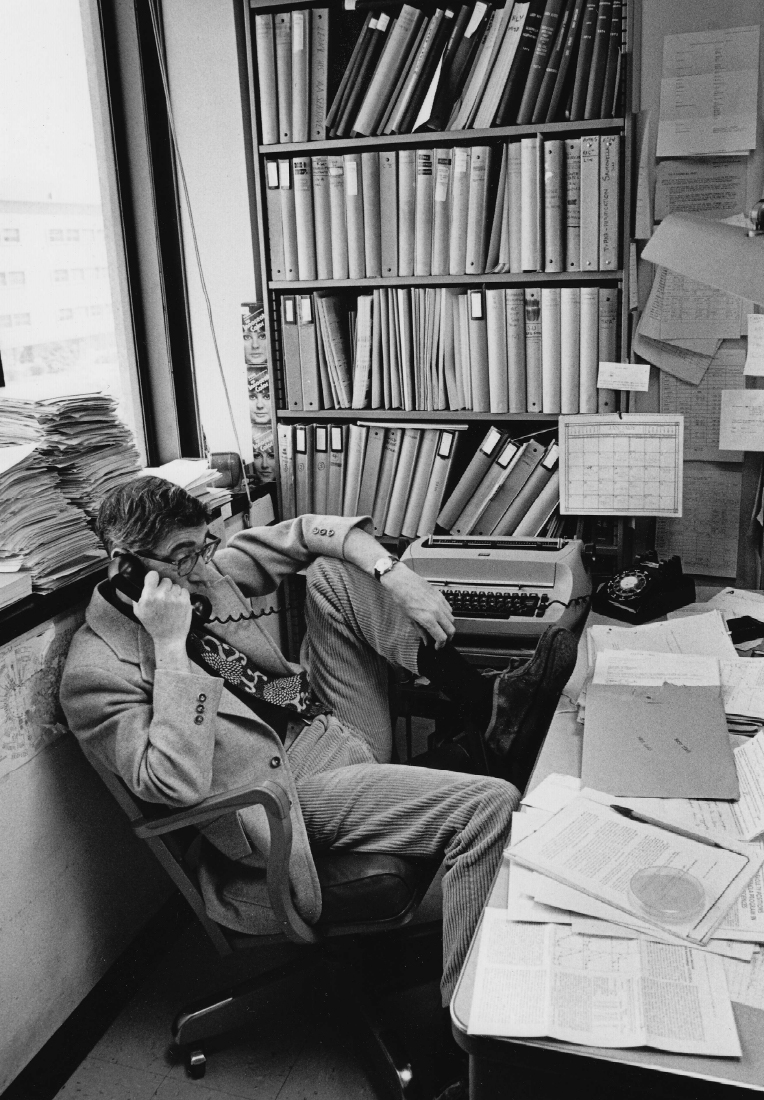

– Paul Burnett

From the OHC Director: July 2020

Every year as the semester comes to a close, the Oral History Center hosts a very special event. We call the event our annual Commencement celebrating the Oral History Class of that year. We invite campus friends, project partners, and everyone (and their families and friends) whose oral history we completed in the previous year. Every year this has been a joyous and often moving event. Every normal year, I should say, as we were unable to gather our community together this year. So, like almost every other social gathering, we’ve decided to host our commencement virtually by devoting and dedicating this newsletter to the Oral History Class of 2020. In articles within, you’ll be treated to thoughtful reviews by our interviewers on the past year’s oral histories. We’re also including a feature on a podcast produced by undergraduate Miranda Jiang, which was originally planned to be a live performance at the event. And we’re announcing Ricky Noel as the first winner for the Carmel and Howard Friesen Prize in Undergraduate Oral History Research, which we had hoped to award at the commencement.

This year I’ve also decided to hand over the honor — and the duty — of the commencement address to my very able colleagues at the Oral History Center. Several of the Center’s interviewers have written about their interviews from the previous year, offering well-considered thoughts on what they learned and on what valuable lessons might be drawn from those voices now preserved in our archive. These four “commencement addresses” are worth reading on their own, but taken together they offer a compelling answer to the question: why is oral history unique, or perhaps better, what can oral history uniquely teach me?

Amanda Tewes focuses on her several interviews for the Getty Trust Oral History Project and reveals that conducting interviews — and setting the framework for conducting successful ones — has taught her a great deal about humility, and how humility takes work and planning. Roger Eardley-Pryor contributed a thoughtful piece showing how oral histories uniquely show how expertise is rarely a solitary achievement but one that is possible because of mentorship, collaboration, and even rivalry. Shanna Farrell centers her many interviews for the East Bay Regional Park District project and highlights the many diverse people who need to work together to make something that we too often take for granted — in this case, open space and parklands. Finally, Paul Burnett reflects on the moments in interviews when narrators revealed a failing — personally or institutionally — and struggled with how to respond and how to accept responsibility. I think each of these “commencement addresses” demonstrate not only the breadth and depth of OHC’s collections but also, and equally importantly, that contained within these interviews are innumerable lessons learned and now shared over the narrators’ collective hundreds (or thousands) of years of experience. They show that we are capable of making mistakes but also correcting them, that we change as we grow and often strive to do better. I am thankful for these contributions by my amazing colleagues, as well as for a culture of open dialog that allows people to acknowledge past difficulties without sanction as they themselves pursue a better path forward.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Oral History Center

The Meaning of Taking Responsibility

These times pose great challenges for us as individuals and as a nation. We are being called upon to look beyond our own narrow interests and to make changes in our behavior to keep ourselves and others safe. In reflecting on my interviews over the past year, most of which are not yet publicly available, I see people who have identified problems and engaged with them directly. I see people having hard conversations, which includes taking some degree of responsibility, either personally or institutionally, for something that has gone wrong, or that has been going wrong for quite some time. I see people who act in accordance with their values.

In the San Francisco Opera project, I see Dramaturg Emeritus Kip Cranna and former General Director David Gockley having difficult conversations about budgets and staffing during periods of crisis, which, in the arts, is always a relative term. I see former UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau spending a lifetime advocating for the excluded and disadvantaged, and taking criticism after making difficult administrative decisions. I see Susan Graham—one of the first professors of computer science at UC Berkeley—participating in the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology that was established during the Obama Administration, which recently warned the federal government of the urgent need to replenish the national stockpile of personal protective equipment that had nearly been depleted after the H1N1 pandemic. And although I did not conduct the interview with nurse administrator Cliff Morrison, I felt close to his story, as it features prominently in the podcast I worked on about the early years of the AIDS epidemic. After spending a career caring for people living with AIDS, Morrison is currently participating in a study of the long-term effects of COVID-19, having contracted the disease while performing similar acts of service in this latest pandemic. In Cliff’s story, he took the step—audacious for the early 1980s—of asking patients what they needed and providing it for them, overriding an established hierarchy in the hospital by doing so. Although he was not the first to suggest patient-centered care, his act of courage was an important catalyst for the development of the “San Francisco Model” of nursing care that has since become a standard around the world.

But one of the interviews that really stays with me is with Bob Kendrick, who had a 60-year career in the mining industry. He tells a story of a mine accident that happened while he was the superintendent. What he relays in the story—and the fact of his telling it—is an example of taking responsibility that I take to heart.

And finally, there’s the oral history of George Leitmann, an engineering science professor at UC Berkeley who returned to Europe and risked his life to fight the Nazis and to make the world a better place.

In recent months, we have all been reminded, again, of the call to respect one another and to act to reduce harm to others, whether this involves simple acts of observing public health recommendations or speaking out and acting against organized discrimination, implicit bias in our own work, and systemic problems with police brutality against African Americans. Many of the oral histories listed below are examples of people who have spent their lives serving some idea of the greater good. I am grateful to all of my narrators this past year for reinforcing the importance of stepping up and taking responsibility for the world we live in, and the world we want to live in.

This year, we celebrate the completion or near-completion of the following interviews:

Bob Kendrick – Global Mining and Materials Research

George Leitmann – University History

John Prausnitz – University History

Bruce Ames – University History

Robert Birgeneau – University History

Susan Graham – University History

David Gockley – San Francisco Opera

Kip Cranna – San Francisco Opera

George Tolley – Economist Life Stories

Winner of the Friesen Prize in Oral History Research

Announcing the Winner of the First Annual Friesen Prize in Oral History Research

Announcing the Winner of the First Annual Friesen Prize in Oral History Research

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce that the winner of the first Carmel and Howard Friesen Prize in Oral History Research is Ricky Noel, for his paper, “Corporate Imperialist Medicine: Aramco’s Health Care Initiatives in Saudi Arabia 1945–1965.” Mr. Noel is a Berkeley undergraduate majoring in history.

The selection committee read the several submissions for the following criteria: How well oral histories are integrated within and essential to the overall essay; how creatively oral histories are used in the essay; and the overall quality and persuasiveness of the essay. Noel’s essay excelled in all three areas. Particularly notable is the fact that his paper demonstrates how oral history interviews can be a crucial, even transformative, source from which new and enlightening historical interpretations can be drawn. Noel drew upon the interviews of the ARAMCO project, which consists of twenty-one oral histories covering the history of the US-Saudi oil operation founded in the 1930s and then sold to the Saudis in 1980.

We applaud Mr. Noel for digging deep into the archives, reading through long and detailed oral histories, and, in the end, hitting pay dirt in terms of fascinating and consequential archival discoveries, such as the public health dimension to US investment in overseas industrial ventures, as is covered in this essay. In this time of remote research, we encourage all students to explore the 4,000 interviews in the Oral History Center online collection and, like Ricky Noel, produce meaningful original research.