Manuscript Collections

Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: This is Not a Fish Story , This is a Fish Story

What would it be like to fly halfway around the world on a non-stop flight from Newport, Oregon to Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland aboard a C-17 Air Force transport plane with a small crew of environmentalists, veterinarians, and an internationally famous 21-foot long, 10,000 lb. orca “killer whale”?

Detailed answers to that question and much, much more can be found in the Earth Island Institute records, a newly processed collection now open to researchers at The Bancroft Library.

Earth Island Institute is a Berkeley based non-profit conservation group founded in 1982 by David Brower that acts as an incubator to support a global network of ecological and social justice projects working to conserve, protect and restore the environment. Born in 1912, Brower entered the University of California at Berkeley at age 16 with a plan to study entomology, but due to financial pressures had to leave school by his sophomore year.

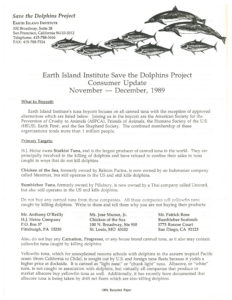

Located in the David Brower Center in downtown Berkeley, you may have walked by or visited the LEED Platinum rated building, read the Earth Island Journal publication, or be familiar with Earth Island’s work going back to the late 1980s on the dolphin-safe tuna campaigns. Those campaigns helped to heighten awareness of dolphin by-catch mortality levels during purse seine net and drift net fishing practices for tuna fish, reform marine mammal protection laws and establish the dolphin-safe tuna labels.

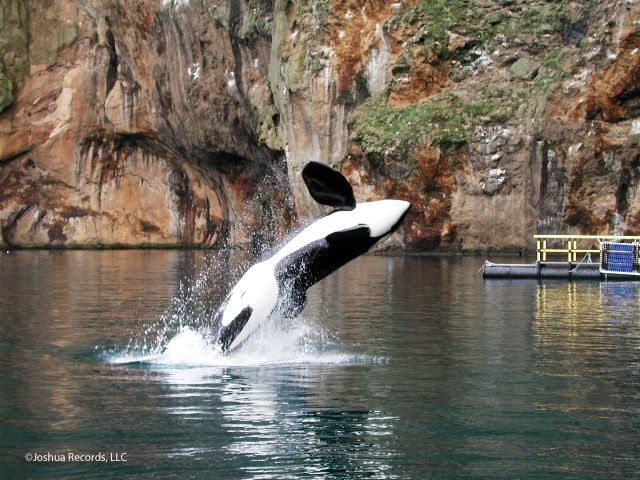

One of Earth Island’s other major projects began in 1994 after the film Free Willy was released by Warner Bros. and brought worldwide attention to the plight of captive marine mammals everywhere, although especially for the orca “killer whale” known as Keiko who starred as Willy. First captured off Iceland in 1979, Keiko was owned by Reino Adventura, a theme park in Mexico City, Mexico during the film’s production. After Earth Island Institute, numerous animal welfare groups, environmentalists and children from around the world rallied to free Keiko, Reino Adventura agreed to donate him to the newly formed “Free Willy Keiko Foundation” for a program of rehabilitation at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport for eventual release back to the wild.

What happened to Keiko from then on is now in the historical record and up for research and debate. Although Keiko was released back into the wild, first into the Iceland sea pens in September 1998 and then into Iceland’s open waters, he died off the coast of Norway in December 2003 from pneumonia and possibly hunger, having lost the ability to fish for himself after being held captive so many decades. Since 1961, hundreds of killer whales, or orcas (actually a type of dolphin) have been captured and used in theme parks to entertain, and some would argue to educate, the public on the beauty and wonder of these magnificent beings.

As of 2018, there are approximately 60 captive orcas and countless dolphins and other marine mammals being held and used for entertainment at theme parks primarily in China, France, Japan, Russia, Spain and the United States. And yet, captive orcas are certainly not the only killer whales in harm’s way. As evidenced in a number of recent studies, films and news stories – orca populations in the wild are dwindling at rapid rates as declining fish stocks, marine pollution and other factors like increased shipping traffic have caused them to be at extreme risk for extinction. The time to learn about orcas, marine mammals, the greater ecosystem of our world environment and how we can improve life for all creatures of the land, air and sea is now!

The processing of the Earth Island Institute records is part of a two-year NHPRC-funded project to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

Environmental Justice Grit in the Borderlands

Environmentalists make terrible neighbors, but great ancestors. – David Brower

It would be difficult not to notice a common thread of diligent, dogged persistence across the broad spectrum of environmental justice activism. This tenacity, coupled with a long view of the world and a whole lot of hard work, is what makes for some of the most successful environmental justice campaigns.

While success cannot be measured in one brief moment or win where environmental issues are concerned, each victory adds to the larger picture of global environmental awareness and health of the planet. Multiple stories of such environmental justice grit can be found in the collections at The Bancroft Library and one collection in particular is the newly opened records of Arizona Toxics Information.

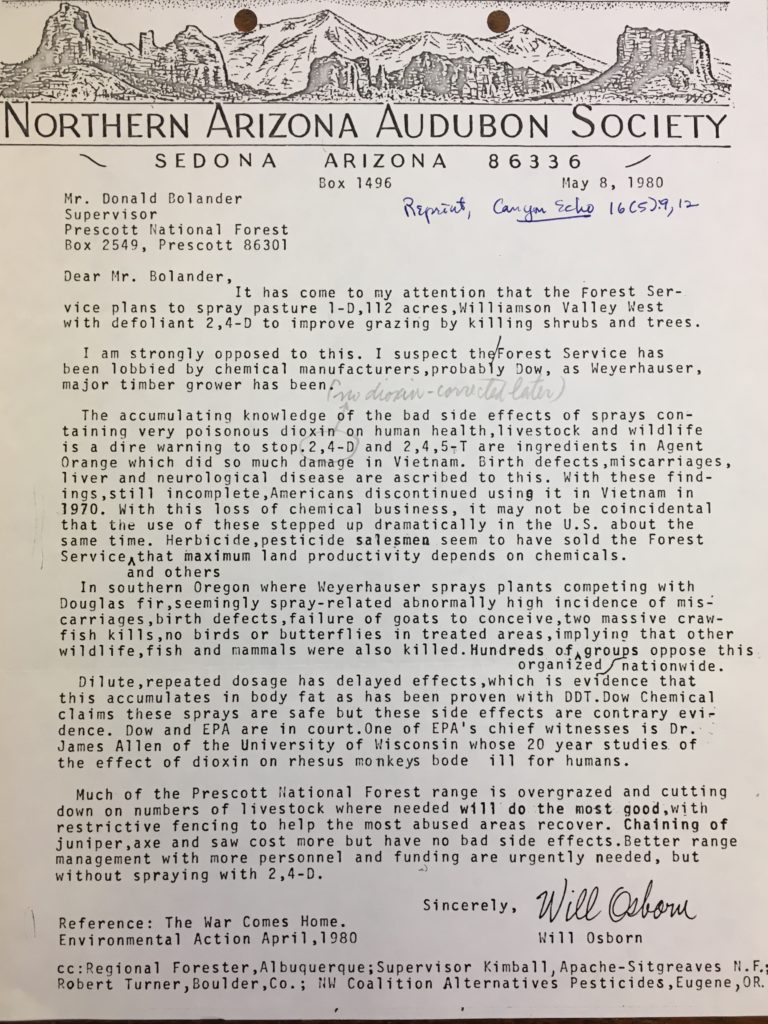

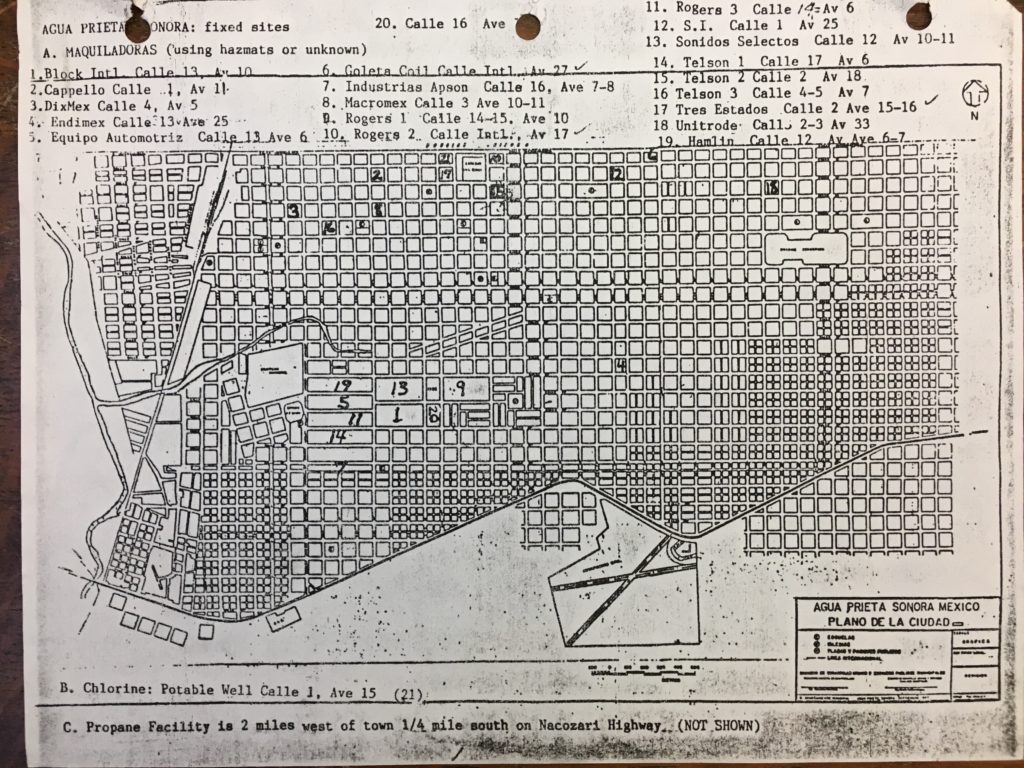

Focused primarily on environmental concerns in the Arizona/Mexico border region during the 1970s through 1990s, Arizona Toxics Information was founded by conservationist Michael Gregory in 1990. The collection also includes materials collected by Gregory before Arizona Toxics Information was established when he worked with the Sierra Club Grand Canyon Chapter and grassroots environmental groups. Gregory had been employed by the United States Forest Service in the early 1970s and had witnessed the spraying of herbicide 2,4,5-T in national forests while he was stationed at fire outlook towers. 2,4,5-T is one of the main components of Agent Orange, which had already been banned for use in Vietnam due to its known harmful health effects and birth defects. From there, Gregory set about to research, collect information, write articles and lobby to end the practice of herbicide, pesticide and insecticide spraying in national forests and range lands.

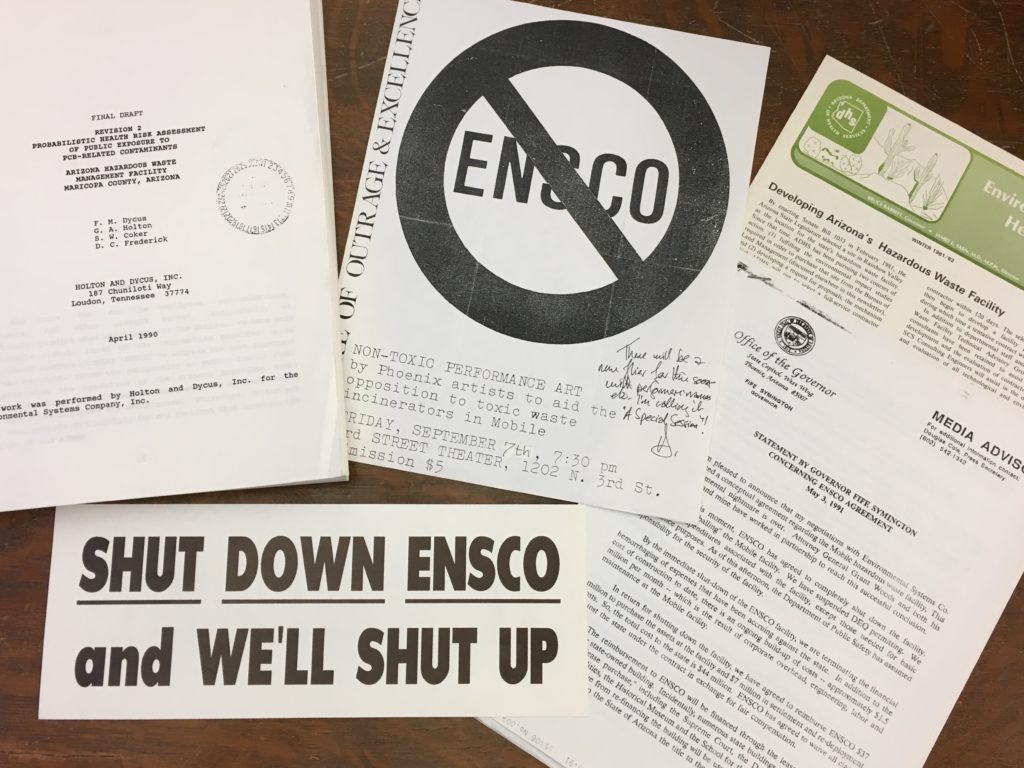

In addition to the fight for pesticide use awareness and regulations, Arizona Toxics also ran several successful campaigns to shut down the Phelps-Dodge Corporation’s Douglas Reduction Works (copper smelter), the ENSCO hazardous waste management facility (PCB incinerator), and to improve the overall air and water quality of Arizona. As the Environmental Protection Agency’s Integrated Environmental Plan for the U.S.-Mexico Border Area and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) were being drafted in the early 1990s, Arizona Toxics Information lobbied and organized grassroots groups on both sides of the border to share information and rally for a multitude of environmental commitments in the agreements. These commitments included providing the public the “right-to-know” about pollutants being released from factories on both sides of the United States-Mexico border, regulating maquiladoras (factories in Mexico that are generally owned and operated by foreign companies which assemble products often to be exported back to the country of that company), and developing emergency disaster plans to respond to hazardous waste accidents.

The current status of NAFTA casts some doubt on the future of these agreements. The opening of the records of Arizona Toxics Information provides timely documentation of hard-won environmental justice victories on the US-Mexico border.

The processing of the Arizona Toxics Information records is part of a two-year NHPRC-funded project to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

NHPRC Supports Processing Environmental Collections at The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library is currently engaged in a two-year project funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

Among the library’s environmental holdings are the records of the Sierra Club, including correspondence of naturalist and Club founder John Muir, the records of the Save-the-Redwoods League, and the records of Save the Bay. Among the collections already made available to researchers in this current NHPRC-funded project are the records of the Coalition for Alternatives to Pesticides, the records of the Small Wilderness Area Preservation group, the papers of environmental lawyer Thomas J. Graff, and the records of California-based Trustees for Conservation. Collections scheduled to be processed in the next eighteen months include the records of such major environmental organizations as Friends of the River, Friends of the Earth, the Rainforest Action Network, and the Earth Island Institute.

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow? The Value in Collecting Social Movement Ephemera

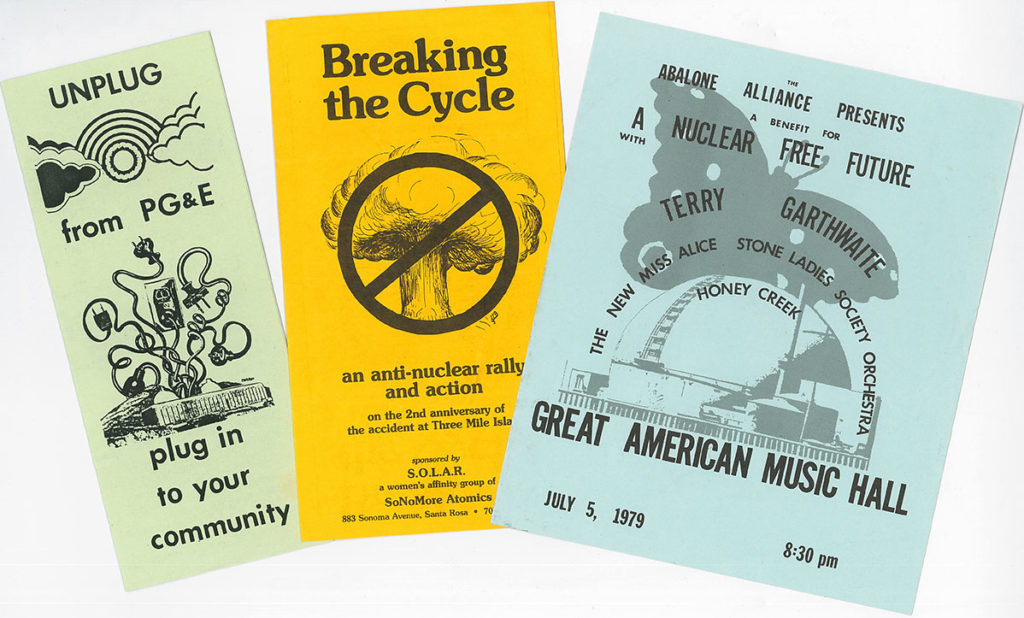

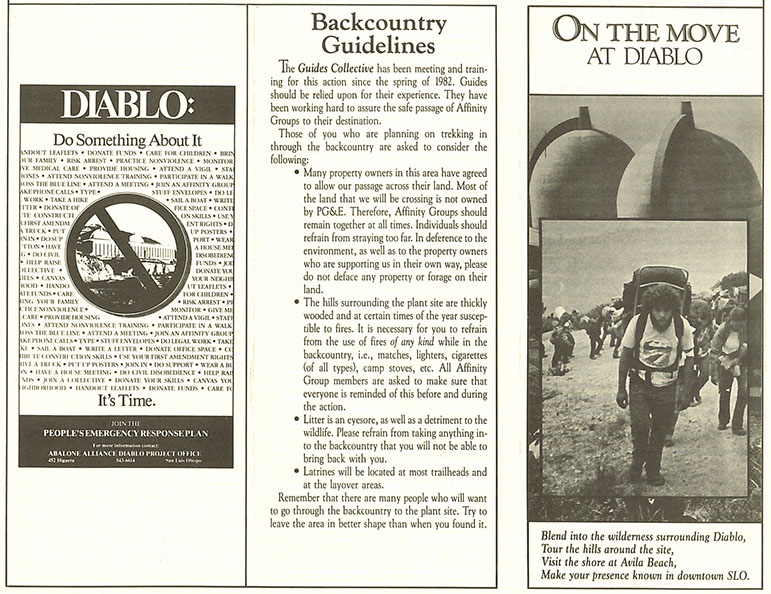

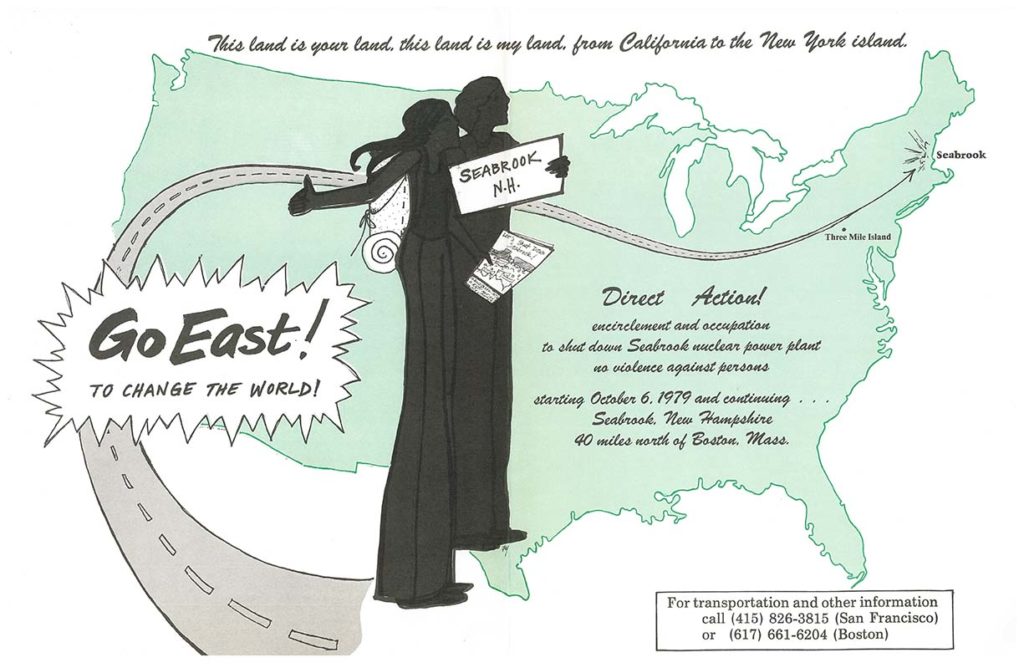

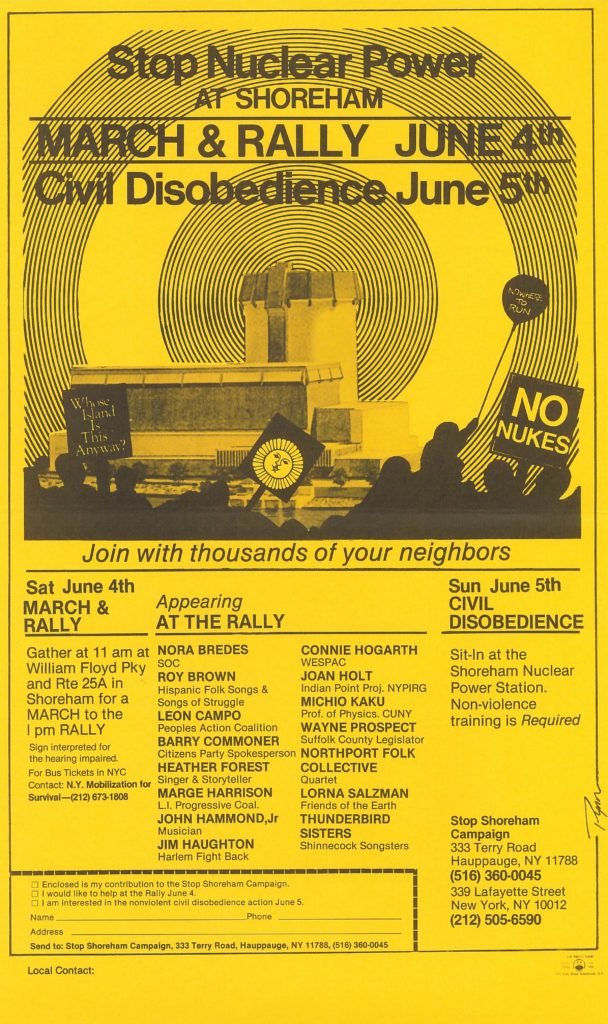

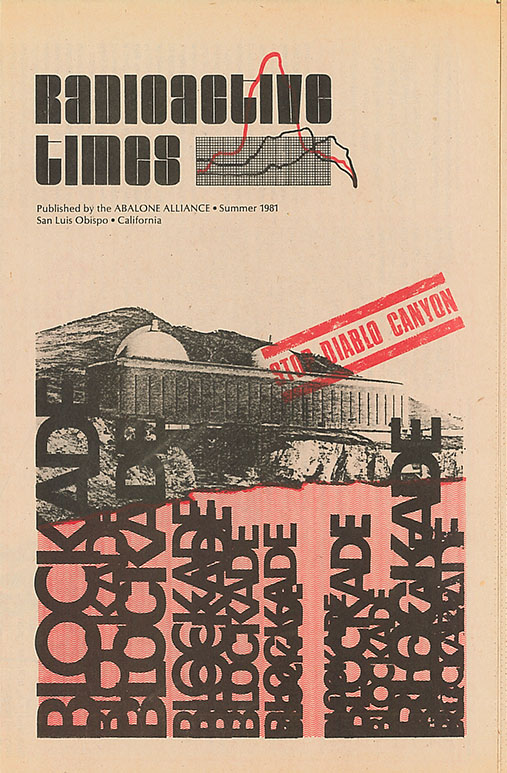

While surveying the Mark Evanoff papers recently during archival processing, it soon became clear that this collection includes a particularly rich array of social movement cultural ephemera about the regional and global environmental impact of the nuclear industry in California. Social movement ephemera is produced in a variety of formats to engage, transform and promote direct action toward a dynamic social cause. The content provides a unique glimpse into a time and place in the life of a socio-political movement and so can be of particular historical importance and value in research and instruction when available.

As objects of a temporary nature, ephemera is always at risk of disappearing once its initial purpose has been served. Accordingly, it usually must be saved by a participant or observer around the time of its creation. This is the case with the Mark Evanoff papers. Evanoff worked primarily with the Abalone Alliance and Friends of the Earth during the 1970s and 1980s to oppose the development and operation of nuclear power plants in Diablo Canyon and Humboldt Bay. He wrote articles for Friends of the Earth’s “Not Man Apart” publication, planned and participated in protest actions (and was arrested twice in the Diablo Canyon blockades), mobilized activists and prepared groups for non-violent civil disobedience training and legal defense.

Evanoff also collected and disseminated educational resources about nuclear power and disarmament produced by local and global pro-nuclear and anti-nuclear groups. The Evanoff papers provide substantial evidence of the anti-nuclear movement, community organizing, direct action and social movement participation at a grassroots level during this period through the correspondence, organizing notes, meeting minutes, legal testimony, public policy clippings, and ephemera contained within the collection.

Since adapting to communication trends is crucial in the progress of social movements, the choices made regarding the information, language, graphic design, artwork, printing and distribution of ephemera produced by these groups can profoundly affect the message. With just a few images and well positioned text, effective social movement ephemera opens minds, pulls at the heart-strings, and/or gets the viewer’s blood boiling and ready for action. It acts as a useful educational and marketing outreach tool to share information, promote ideas, publicize an agenda and provide talking points about a cause. Activist ephemera also usually presents logistical details as to the who, what, when, why, where and how of community organizing, grassroots public policy lobbying, protest marches, fund raising concerts and other actions.

Ephemera is most powerful when designed with eye catching, bold, trending or symbolic imagery, visual cues and creative use of text, colors and fonts. Many flier, poster and zine designs have a cut and paste, DIY (Do-It-Yourself) quality: utilizing photographs overlaid with other compelling graphics and text, including well-known historical quotes or humorous catchphrases, and self-published at home or printed at copy stores. While some other ephemera is professionally graphic-designed and printed on finer quality papers.

Although some materials are undated and may contain questionably reliable content, requiring additional sleuthing to fact check information and find accurate dates, much cultural ephemera can provide valuable incite to researchers long after the date of creation. Social movement ephemera may also act as a jumping off point for scholarly research when used in exhibitions, publications and instruction. The visual aspects and originality of content of this sort of cultural ephemera has the ability to draw a viewer in to study a topic they otherwise may not have known or thought much about previously.

Some of the qualities that make activist ephemera unique can also become challenges when preserving a collection of archival materials. Certain items may be difficult to stabilize and store long-term in their entirety when produced on acidic paper, fabric, metal, plastic or wood; or when they are found adhered to the pages of scrapbooks or attached to handles. There may also be questions as to how best to organize and catalog ephemera materials within a large collection, so that a potential researcher will be able to readily find relevant items. To highlight the research value of the ephemera in the Evanoff papers, it has been arranged so that anti-nuclear materials are separated for the most part from power plant information and nuclear power subject and technical files, and it has been described within the finding aid in a bit more detail than usual.

After nearly 60 years of controversy since construction began on the Diablo Canyon Power Plant, PG&E announced plans for its closure in 2025. While it’s impossible to measure the effect that the activist ephemera produced by the Abalone Alliance and other anti-nuclear groups had on this result, it is easy to see the informational, evidential and aesthetic value in keeping these social movement materials for future researchers. What is important to the historians of tomorrow must be collected and saved today.

The Mark Evanoff papers are now processed and open to researchers at The Bancroft Library.

What’s In a Name? How One Bancroft Library Archivist Shed Light on a Gold Rush Era Gem

Background: Each year the Bancroft Library acquires a sizeable amount of new manuscript material. The sheer quantity of this material necessitates that the archivists who handle, process, and catalog these materials, exercise considerable judgment in balancing thorough and accurate descriptions that facilitate access with the need to make the materials available as quickly as possible. Archivists are trained to determine just the right level of description to allow for sufficient discovery. In the case of very large collections, an archivist rarely describes materials at the item-level.

But sometimes a single item merits closer examination and considerable research to render it truly accessible to the library’s researchers. One such item recently caught my attention–

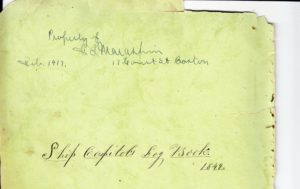

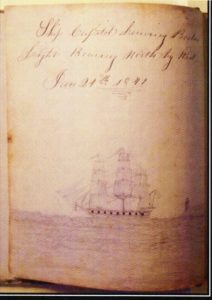

The “Ship Capitol’s Log Book” is the account of a passenger aboard one of the first ships to head to California during the gold rush, arriving in San Francisco in July 1849.

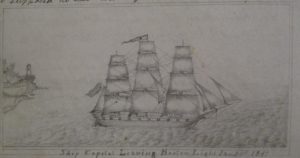

At first glance, it looked like a typical gold rush era journal, with daily entries describing conditions and life aboard the ship as it made its way from Boston to San Francisco around Cape Horn. But this one stood out because it included several finely rendered pencil drawings throughout including ships, shorelines, and even an albatross at rest.

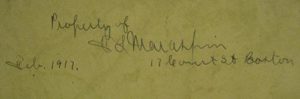

Unlike similar journals that have crossed my desk, this one came with a contemporary inscription inside the front cover identifying the ship and giving the date (and, incidentally, providing a neat title for the catalog record). The accompanying description provided by the vendor was also intriguing, noting that there was an additional inscription in a different hand: “Above this [title] is the inscription of Paul Maraspin, another passenger on the ship and the ancestor of the log’s most recent owner…. It is not clear who authored the journal.” However, upon closer examination, I determined that this might not be the case. It was clearly two initials followed by “Maraspin” but it didn’t look like either a “P” or “Paul.” I could not clearly make out the first initial, but the second one looked like an “L,” and below that a street address of “17 Court Street, Boston” and the date “Feb. 1917.”

The vendor also noted that the lettering of the captions of the drawings was in a third hand, suggesting that someone other than the author of the journal might be the source of those. Also noted was the composer of several songs recorded in the journal, B.F. Whittemore.

The clues from the vendor and my own initial assessment of the journal suggested that a bit more research might make the journal infinitely more discoverable and useful. I became intrigued by the name of the owner of the journal, and the information suggested by the vendor just didn’t seem to fit with the facts the artifact was presenting to me.

Archivists have at their disposal the same research tools many other people do…the internet and access to genealogical sites that hold various records. There is a tremendous amount of information out there that makes this kind of research much more efficient than it used to be. Of course, too much information can also be problematic and it is the skillful researcher who can quickly sort through large amounts information and surmise whether more research will yield tangible results or, lacking that, have to call the effort “good enough.”

In this particular case, I discovered information about the owner’s signature that led to the solution of numerous puzzles presented by the journal itself, including how he came into possession of it, its likely author, the identity of the illustrator, the history of the lyricist of several songs, the author of the final song in the journal, and the history of the ship and its captain, Thorndike Procter.

Because Maraspin struck me as an unusual name, my first step was a Google search on the name. This resulted in the discovery of a Maraspin Creek in Barnstable, Massachusetts. Assuming the creek was named after a prominent family in the area, the information gave me hope that I could find out more about them and explore those connections.

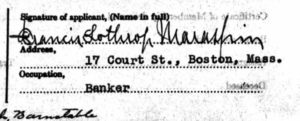

I switched over to Ancestry.com to do a direct search on Paul Maraspin from Barnstable, Massachusetts around the time period of 1849. Numerous records surfaced that indicated a Paul Maraspin from Barnstable had been married and had several daughters, but none of whose initials matched the inscription in the journal. But then I found an application to the Sons of the American Revolution from 1937 for Paul Maraspin that listed his wife, Mary Eliza Davis, and one child, a son, Francis Lothrop Maraspin. Paul Maraspin had this son rather late in life, at the age of 52, and some 16 years after he had sailed to California. Looking back at the inscription, I could see now that the autograph was, in fact, “F.L. Maraspin.”

I then turned to confirming that this was, indeed, the Francis Lothrop Maraspin in the application form. Back to Google, I found an article from the Cape Cod Times lauding a Francis Maraspin’s 100th birthday in 1966. Back to Ancestry.com I found another Sons of the American Revolution application from 1935, this time for a Francis Lothrop Maraspin. I could see print coming through from the backside of the page and paged forward to see it. Right at the top was the statement identifying Paul Maraspin as his father. But the real clincher was at the bottom.The application was signed by Francis Lothrop Maraspin himself with his typed address, 17 Court Street, Boston.

And from the journal again:

As you can see, the signature and address matched the inscription on the journal cover perfectly and we now knew we had our owner and could assume, with reasonable certainty, that the likely author of the journal was Francis Lothrop’s father, Paul Maraspin.

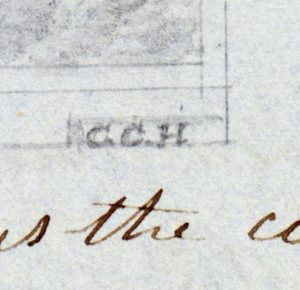

I shared these initial findings with my supervisor, Randal Brandt, who directed me to a publication that would be key to figuring out the rest of the puzzles. The Argonauts of California, published by C.W. Haskins in 1890, is an invaluable source of information about the gold seekers who came to California. The passenger lists it contains were crucial in figuring out the names of people associated with the journal. We now knew who had written the journal but who had done the drawings? And what about the composer of those numerous songs recorded in the journal? A closer examination of the drawings proved fruitful. Of the nine drawings, two of them had the initials “CCH” in the lower right hand corner.

A quick perusal of the Capitol’s passenger list turned up only one possible match, a C.C. Hosmer. Now we knew the name of the illustrator. Back to Ancestry.com again, I went hunting for more information about him and found out his full name, Chester Cooley Hosmer (1823-1879). Because Chester Cooley Hosmer is also an unusual name, on a whim I Googled it along with the word “Capitol.” The very first result was a library catalog listing in the Special Collections of the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts for Chester Cooley Hosmer’s journal documenting the same trip aboard the Capitol. Describing it as a journal “illustrated throughout with his drawings,” the catalog listing included scans of two pages with drawings. Here is one of them.

One can readily see the style of these drawings match those in the Maraspin journal. Not only did we now know our illustrator but also the location of his journal from the very same voyage.

Turning to the name listed as the songwriter, B.F. Whittemore (sometimes spelled incorrectly as “Whitmore” in passenger lists), a search turned up another interesting character. The Wikipedia entry for Benjamin Franklin Whittemore states that he went on to become a minister in the Union Army and then elected to the state legislature of South Carolina and eventually the House of Representatives.

Others identified in this process included the composer of the final song lyrics in the journal titled, “A Song Dedicated to the Officers of the Ship Capitol,” and signed “W.T. old friend.” Again, the passenger lists were the key as only one person had those initials, W.T. Hubbard.

More research on the ship and lists revealed the full name of the captain, Thorndike Procter of Salem, Massachusetts.

As might be true with any group of persons traveling so far from home for so long, there is inevitable tragedy as well as triumph. Captain Thorndike Procter committed suicide in San Francisco Bay on October 17, 1849. It was reported in the papers that the captain “had been lately subject to occasional fits of derangement, during the last of which he jumped overboard, and was drowned….” Nine weeks later, Paul Maraspin’s young “old friend,” William.T. Hubbard, just 23 years of age, also died by drowning in San Francisco Bay on Christmas Eve.

The work of improving access and discoverability to our collections is at the heart of what we do as library professionals. Unknown people become known, their stories and lives become real to us, and as you read this journal now you can see the intertwining of their lives. One hundred and sixty-eight years later, two journals from the same trip are virtually reunited because of the work of archivists and catalogers separated by time and a continent. In this way, library professionals contribute to a very large cultural jigsaw puzzle that, slowly but surely, becomes ever more complete.

To see the completed catalog record for this item please use this link:

http://oskicat.berkeley.edu/record=b23750637~S1