New Sierra Club Oral History Project interview: Aaron Mair

Aaron Mair is a pioneer in environmental justice and became the first African American president of the Sierra Club from 2015-2017. Mair, whose ancestors suffered enslavement, has dedicated much of his life to overturning the ongoing injustices experienced by Black Americans, including environmental racism. The Power of Place, Mutuality, and Interconnection all arose as important themes throughout Mair’s fifteen-hour oral history, which we conducted over five interview sessions in November 2018, first in Pickens County, South Carolina, and then in Albany, New York, where Mair lives. That week that Aaron Mair and I shared together became one of the most enlightening and powerful experiences in my life as an oral historian.

On the day we first met in South Carolina, just before his first interview session, Mair walked me through an unkept graveyard where his mother’s enslaved ancestors are buried. A few days later, on our final day of interviewing, we walked through snow across the Helderberg Escarpment that rises above the Hudson Valley in New York, near where Mair has lived most of his life. As he informed me, the Helderberg Escarpment is the site where, over 150 years earlier, a Southern slave-owner named Joseph LeConte studied geology with Louis Agassiz and nurtured notions of scientific racism. After the Confederacy collapsed, Joseph LeConte moved west to become a geology professor at UC Berkeley and co-founded the Sierra Club alongside John Muir in 1892. Nearly 125 years later, in 2015, Aaron Mair became the Sierra Club’s 57th president and its first African American president.

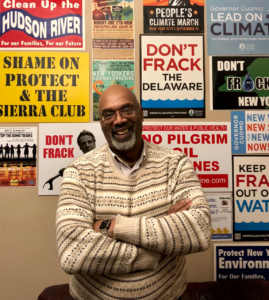

Aaron Mair was born in November 1960. He completed PhD coursework in Political Science at the State University of New York at Binghamton University, and upon becoming a father, he departed as ABD to work for the New York State Department of Health in Albany, where he still works as an epidemiological-spatial analyst. By the late 1980s, Mair’s training in geographic information systems, his graduate readings in World Systems Theory, and his family’s experiences in civil rights and labor organizing all came together in Mair’s campaign to shut down the toxic ANSWERS (Albany New York Solid Waste to Energy Recovery System) incinerator in Arbor Hill, the majority Black neighborhood where Mair and his family lived. The ANSWERS incinerator, which burned trash to produce electricity for the Empire State Plaza where Mair worked, also produced toxic ash that blew directly onto Mair’s family and community. In 1998, after a decade-long battle to close the incinerator, Mair won a landmark $1.4 million settlement with New York state (his employer) for environmental racism. He then used those funds to further his intersectional environmentalism by founding two non-profit organizations: Arbor Hill Environmental Justice Corporation, and the W. Haywood Burns Environmental Education Center. Through these organizations, Mair advocated further for environmental justice, including in the Clean Up the Hudson campaign that forced General Electric to dredge toxic PCBs from the Upper Hudson River.

In 1999, Mair joined the Sierra Club in a conscious effort to reform it from the inside. Years earlier, while still battling the toxic ANSWERS incinerator, Mair sought to partner with the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter in New York City. Instead, the all-white room of Sierra Club members rejected Mair’s overture and said, “Did you check with the NAACP?” However, Albany’s local Sierra Club group did scrounge up early support for Mair’s campaign. With gratitude, Mair vowed that once he successfully closed the ANSWERS plant, he would join the Sierra Club to ensure it would collaborate with communities of color. Upon joining the Sierra Club, Mair held leadership positions at every level, including as group chair, then chapter chair and environmental justice chair in the Atlantic Chapter in New York; as national chair of the Sierra Club’s Diversity Council and of its National Environmental Justice and Community Partnerships; as an elected member to the national Sierra Club board of directors; and as president of the Sierra Club from 2015-2017. Mair became instrumental in creating the Sierra Club’s new Department of Equity, Inclusion, and Justice. Today, he continues to serve as a nationally elected member to the Sierra Club’s board of directors.

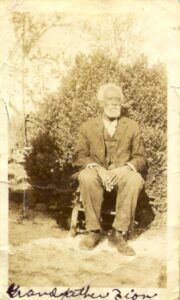

For his Sierra Club Oral History Project interview, Mair insisted we conduct his first interview sessions at the Hagood Mill Historic Site in Pickens County, South Carolina, in part to connect his family’s heritage of enslavement, emancipation, and environmental stewardship there to the life of Confederate slave-owner, Sierra Club co-founder, and UC Berkeley professor Joseph LeConte. (In November 2020, UC Berkeley officially removed the name LeConte Hall from its Physics Department building on campus.) According to a historic marker at the Hagood Mill Historic Site, the mill was reconstructed in 1845 by James Hagood, a prominent “planter and merchant” in South Carolina, who served in the state’s House of Representatives. Nothing at the Hagood Mill Historic Site mentioned how Hagood’s money and influence derived from his family’s chattel enslavement of humans, including Aaron Mair’s ancestors. The Mill’s construction occurred shortly after the birth in 1844 of Zion McKenzie, Mair’s great-great maternal grandfather whom the Hagood family enslaved. During his time as Sierra Club president, Mair made that discovery of who, exactly, had enslaved his family after years of deep genealogical research. Documents and photographs from Mair’s genealogical research and his years of activism can be found in the appendix to his oral history.

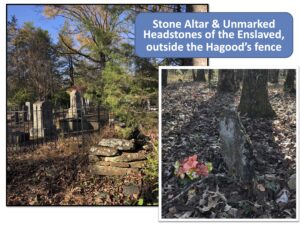

Before Mair and I began recording his first interview session, he showed me another unaccounted legacy of his family’s history at the Hagood Mill Historic Site. Together, Mair and I visited the “slave section” of the Hagood cemetery in an unkept pocket of land directly next to the well maintained Hagood family cemetery. In contrast to the Hagood family’s ornate headstones and sarcophagi, replete with crosses for Confederate veterans and bounded by a wrought-iron fence, the graves of Mair’s enslaved ancestors were barely noticeable among the fallen leaves. They were marked only by unhewn river rocks set slightly askew as nameless headstones. In that moment, Mair spoke solemnly about the generations of lives lost to slavery, about its ongoing aftereffects, and about the power of public memorials, especially the impact of what is not memorialized.

Mair then pointed to a nearby collection of large stones stacked against a tree to form a roughshod alter. He named the alter as the site of the first Golden Grove Church, the later iterations of which Mair and his family still attend today. Mair spoke then about the importance of faith for his family, and he offered up a prayer before we returned to the Hagood Mill to begin his oral history. Much of Mair’s first interview that day recounted the evolution of his enslaved ancestors’ emancipation from human dominion to their sustainable stewardship of the land where, today, the homes of his South Carolina relatives and the Golden Grove Baptist Church still stand. Those stories about Mair’s ancestors helped to contextualize his own conceptions of environmental responsibility, which later inspired his pioneering work in environmental justice and his leadership within the Sierra Club.

Mair and I completed his final oral history sessions in Albany, New York, in the historic and majority Black neighborhood of Arbor Hill where Mair lived and raised his daughters for many years. During his interviews in Albany, Mair shared stories of his intellectual awakenings in college, the beginnings of his civic and environmental activism in Albany, his pioneering work in the environmental justice movement, and his more-than-twenty-years of effort to help the Sierra Club build bridges across the civil rights, labor rights, and environmental rights movements. Just down the street from one of our interview locations, Mair pointed out the ominous smokestacks rising up from what once was the ANSWERS solid waste incinerator. Mair’s decade-long battle to stop that incinerator from spewing toxic ash onto his family and community changed his life. In the process, Mair became active on so many issues in Albany that it proved impossible for us to record all those stories. However, the patterns I saw in his activism included reclaiming open space for public use, demanding equal treatment by law, ensuring his community’s political voice was heard, fighting toxic pollution, and seeking just recompense from those who’ve done wrong. In many ways, Aaron Mair’s life history, and that of his family, reflect the Sierra Club’s own increased awareness and historical evolution to better incorporate equity, inclusion, and justice in its environmental efforts.

On our final day together, during his lunch break, Mair met me in the Helderberg Mountains just outside of Albany. A light snow blanketed the ground as we walked across the escarpment and looked over the Hudson Valley. The rock and fossil records at the Helderberg Escarpment are so extensive and well-exposed that the site became pivotal to the study of North American geology in the early nineteenth century. Charles Lyell, the foremost geologist of that era, read from his home in England the newest research then done on those rocks just outside of Albany. When Charles Darwin read Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33), it helped Darwin conceive of evolution as a slow process in which small changes gradually accumulate over time. While at the Helderberg Escarpment, Mair reiterated how, in the mid-nineteenth century, Joseph LeConte—a co-founder of Sierra Club in 1892 and a former slave-owner from South Carolina—conducted geological research at that very site with Harvard geologist and white supremacist Louis Agassiz. More than once that week, Aaron suggested how his recent presidency of the Sierra Club, when contextualized by his own life and heritage—including his family’s history of enslavement and emancipation—signified a kind of evolution for the Club, perhaps for the broader environmental movement. Hopefully, both. Mair and I concluded his oral history that evening with an epic interview session that lasted seven hours. We emerged to find Albany blanketed in four inches of fresh snow.

By the time I landed back in San Francisco the following day, the then-deadliest and most destructive fire in California’s history, the Camp Fire, had already decimated the town of Paradise and, over the next week, continued scorching some 240 square miles of land, taking with it many people’s lives and livelihoods. Ash from that horrific fire rained down on my wife, myself, and our one-year-old daughter in Sonoma County, even though we lived more than 150 miles from the inferno. Smoke from the blaze made the Bay Area’s air quality the worst of any place on the planet and rose to levels federally designated as dangerous. The hazardous air and unavoidable soot falling on my family made me think of Mair’s efforts to stop the ANSWERS incinerator from raining toxic ash on his children. And it reminded me how current Sierra Club campaigns against climate change are, in some ways, efforts toward climate justice for us all, but especially for our children and Earth’s future generations.

Aaron Mair’s oral history is part of the Sierra Club Oral History Project, a longstanding partnership between the Sierra Club and the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library that began soon after the first Earth Day in 1970. For fifty years now, the Oral History Center has partnered with the Sierra Club to produce, preserve, and post for free online an unprecedented testimony of engagement in and on behalf of the environment, as told by well over one hundred volunteer leaders and staff members active in the Club for more than a century. However, few of those interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project share stories of the Club’s evolution toward environmental justice. The publication of Mair’s interview begins to fill that lacuna, and I hope we can record more powerful stories from Sierra Club members and staff leaders who, similarly, helped move the Club on issues of environmental justice. In his interview, Mair revealed how his life experiences and ancestry intersected with the Sierra Club’s evolving efforts on diversity, inclusion, and justice. Many more stories from that journey need to be shared. I’m deeply grateful Aaron Mair shared his story with me.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

You can read Aaron Mair’s oral history here:

For related work in the Oral History Center’s renewed Sierra Club Oral History Project:

See our oral history of Michele Perrault, who became the first female president of the Sierra Club in its modern era, twice elected as national president from 1984 to 1986 and from 1993 to 1994.

See this post on Intersectional Progress through Women in the Sierra Club, which highlights research by Ella Griffith (UC Berkeley Class of 2020) on “Sierra Club Women” — an annotated bibliography of women’s oral histories conducted between 1973 and 2018 for the Sierra Club Oral History Project.