“Female Consciousness and Environmental Care”

(Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program, Spring 2019)

By Ella Griffith

Ella Griffith is a rising senior at UC Berkeley majoring in Environmental Science, Policy, & Management (ESPM) within the College of Natural Resources. In the Spring 2019 semester, Ella worked with historian Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. Ella’s research projects included analysis of the Oral History Center’s exceptional archive of interviews with Sierra Club members, which resulted in this month’s “From the Archives” article.

The work of the Sierra Club has, over time, evolved beyond outdoor exploration and advocacy for natural spaces to make marginalized identities central in its efforts. For my Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP) project in Spring 2019, I began looking for historical narratives about environmental justice in the Oral History Center’s interviews with Sierra Club members. As one of the oldest and largest conservation organizations in the United States, the Club has been scrutinized historically for its elite membership and prior lack of intersectional awareness around environmental issues. I determined, however, that the Club’s evolution toward holistic inclusivity—environmental and social—can be credited largely to the fierce, wonderful women who played, and continue to play, a role in shaping the Club’s future. As such, the nuanced roles and perspectives of women in the Sierra Club emerged as the captivating focus in my URAP research.

As a young woman and fellow environmental activist, I cherished reading other women’s personal and environmental perspectives, especially on the challenges they faced and the empowerment they experienced through their work within the Sierra Club. The themes and issues that the women spoke on remain relevant to today’s gendered issues. Their narratives built upon one another, and in the end, I could not escape feeling that what remains, in the present, is me. Women today expand on the layers of work that earlier women set down before us. Women activists—environmental and otherwise—stand now where we are because earlier women were not satisfied with where they were. But the process of change remains slow. Through these oral history interviews, we can learn more about the work that has been done, to help us understand what is left to do. As a result, the Sierra Club’s developing scope of work on equity, and the narrative of its adaptation, is important in understanding inclusivity in the greater environmental field.

In the Sierra Club’s oral history collection, I found generations of women’s stories. These archived interviews with women reflect a development of female consciousness threaded through the common denominator of love and care for the environment. As I read more interviews, vibrant patterns emerged. Women in the Sierra Club spoke similarly on the themes of fierce activism rooted in family values, of nature as an equalizer, and about the role of women in leadership positions within the Club. Other recurring motifs were less empowering, such as inequality in resources, the cult of domesticity demarcating women’s roles in the Club, and perhaps a more abstract trend of women’s apparent value as interviewees because of their proximity to prominent men in the Club. But on the whole, women explain in these oral histories how fundamental they have been to the Sierra Club’s successes, from its earliest days through the present. Below, I briefly explain some of these themes and offer quotes from various interviews that directly relate to it.

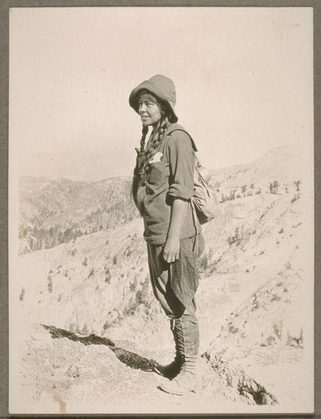

Nature as an Equalizer: At its most optimistic roots, the Sierra Club’s founders appreciated the outdoors and the mutual enjoyment of exploring natural landscapes. Several older female interviewees described early twentieth-century “High Trips” in the Sierra Nevada backcountry as joyous outings where neither man nor woman was restricted to any particular role. Rather, all “outings” attendees contributed as part of an innocuous group that moved through the wild landscape. Women spoke of their physical endurance and the power their own bodies gave them—they led backcountry trips and wore pants before women were “supposed” to be leaders or wear pants! From the Sierra Club’s earliest years, hiking and an intimate connection to the outdoors has remained a means for empowering women.

- Born in 1897, Cicely M. Christy attended her first of many backcountry “High Trip” in the summer of 1938, at age 41. She recalled, “The winter of 1937–38 was one of the very heaviest snowfalls the Sierra has had. They had to change the itinerary of the high trip several times because we couldn’t get over passes. A great deal of our first week’s camping was done at 9000 feet, which is despised at any other time! But it was also one of the first times, the only time perhaps, that I really took a pair of boots to bed with me the first night out, to prevent them from being frozen solid in the morning.”

- Recalling tales from her “High Trips” in the 1920s, Nina Eloesser explained, “There was quite a sizable ‘mountain,’ they called it. We wouldn’t think much of it, but it was about six or seven thousand feet up, and it was called Craig Dhu, which meant the ‘black mountain.’ I used to walk by myself, because mother couldn’t. I walked all over that country.” pg 2

- On climbing Mt. Rainier in the late 1920s, Nora Evans noted, “There were seven men, and I was the only woman. I made it to the top successfully.” pg 6

- When asked in the 1970s about women attending early “High Trips,” Ruth E. Praeger replied, “Oh yes. There were always more women than men … but camp was very different then from what it is now. The sexes didn’t mix as they do now.” pg 8

Pioneering Activism: Many Sierra Club women pioneered the Club’s expanding involvement in various issues, from toxins in the environment, to the intersection of women’s health with environmental issues, to a greater engagement with environmental justice. The social contexts of gender roles often showed when some women spoke on their activist work. Many women expressed concern specifically for their children and generally on public health issues, which reflects a conventional focus of women’s activism. Still, these women nuanced their understanding of how complex environmental issues related to one another and stood at the forefront of pushing the Sierra Club’s involvement on these issues.

- Marjory Farquhar joined her first “High Trip” in 1929 and was elected to the Sierra Club Board of Directors in the 1950s. In 1977, when asked about racial discrimination in her northern Sierra Club chapter versus the southern chapter, she replied, “We were far more loose up here. I don’t really remember anything; I just remember myself once thinking, ‘Oh, there are no Japanese or Chinese here—I wonder if I know anyone who would like to join?’” pg 42

- Asked in 1979 for her thoughts on what the Club’s role should be “with regard to broader environmental issues of urban problems, the energy problem, overpopulation,” Cicely M. Christy answered, “All I can do is quote John Muir that if you take up one thing you find it hitched to the whole universe. I think that the Club can leave urban things to other groups, who are more likely to be interested in the urban things than they are in the outdoor natural things. I think that the Sierra Club’s main objective in life, and the thing that they can do best for this country, is the preserving of open spaces and the good air that will keep the open spaces. If you get air pollution you will find that your pine trees in the Sierra are suffering—well, there is not much good in preserving the pine trees in the Sierra if you can’t reduce pollution on the coast. You have to pay attention to everything.” pg 31

- According to Abigail Avery, the purpose of the Sierra Club’s Environmental Impact of Warfare Committee in the 1980s was “to point out wherever it’s appropriate, the connection between what is happening in this whole military buildup and the effect it’s having on the natural environment. Our traditional concern with the Club has been the natural environment. What effect is all this having on these other issues?” pg 23

- When asked in the early 2000s how the Club develops coalitions with diverse groups outside its traditional middle-class, college-educated membership, Doris Cellarius replied, “Sierra Club, I think, has always had really good sense about this. Any Club member I’ve worked with in the United States who’s working with people at toxic waste sites goes there to be helpful. We don’t go there to make them be members. We’ve never—this is just something Sierra Club does to be helpful. We want a clean environment, and we love to work with you. That’s continued to be the tradition of our environmental justice work.” pg 43

Women as Nurturers and the Cult of Domesticity: Women activists in the Sierra Club engaged on a variety of environmental issues, but sometimes historical gender conventions limited the scope of their work or shaped the motivation behind it, particularly with issues linked traditionally to women such as children’s health and “nurturing” others. This view of gender roles and subscription to them can be traced back to the “Cult of Domesticity” or the “Cult of True Womanhood”: a framework of gender stereotypes demarcating women as the gatekeepers of the home, the moral compass of society, and generally as nurturers of the public. In several Sierra Club interviews, women described their environmental activism with both overt and subtle explanations either of ways they felt restricted or ways they chose to engage in the Club based on these gendered stereotypes.

- Reflecting on her environmental experiences after her marriage, Marjory Farquhar said, “I will admit that my active rock climbing days disappeared, really perhaps for two reasons: one because I went into the baby-production business, and the other because of the war.” pg. 22

- When asked about the start of her activism in the 1940s, Polly Dyer replied, “I got involved in conservation by meeting [my husband] John Dyer on top of 3000-foot Deer Mountain [in Ketchikan, Alaska] … Conservation by marriage. I would have gotten into it eventually, I presume, but at least it was an introduction.” pg 2

- Abigail Avery became active in preserving national parks. In 1988, then in her 70s, she recalled how “[My husband Stuart] was the one who first got interested in the [Sierra Club’s] Atlantic Chapter, which was the only chapter in this Eastern area at that time. I remember going on trips with him, but I would go as a wife, you see … I hadn’t really looked at conservation. What I really was concentrating on during that time after Stuart got back [from WWII] was having the rest of my family. Really you cannot maintain everything. You’re not free to do it. So there’s a hiatus in there.” pg 4

- Doris Cellarius shared her view on how gender fits into the environmental movement and what women might bring to it different from men: “I think women just seem to care a lot more about—in the pollution area—about what happens to people, what happens to children. They think more of the long-term consequences of things, and I think they get more outraged that it’s all these men in the corporations that really just enjoy creating these chemicals and building these things that are problems. But I think they have more of an outrage that these things shouldn’t be done to the environment or to people.” pg 53

Leadership and Gender: Interviews with women focused on their work within the Sierra Club, and several interviews dedicated an entire section to the role of women in leadership positions within the Club. Women discussed the expansion of female leadership, limitations, and regressions. Many interviews explored how the narrator felt about their role and the future directions for women in the Club.

- In 1982, then 85 years old, Cicely M. Christy noted, “On the whole, positions of chairmen [of the Sierra Club Board of Directors] have gone to men until a few years ago, and then people like Helen Burke came in. … [Before the 1970s, women’s work in the Club] was just reflected in each chapter I think. I think people grew out of [that tendency to vote for men], rather deep laid, not exactly prejudiced, but just habits of thought.” pg 34

- In 1979, at age of 38, Helen Burke became an elected Executive Officer on the Sierra Club’s National Board of Directors, while also serving as Board liaison to the Club’s Women’s Outreach Task Force and the Urban Environment Task Force. When asked about women’s leadership within the Club, she replied, “The Club has, in the past, been a rather male dominated institution. I think that’s changing now. We presently have four women on a [National Board of Directors] of fifteen, which is roughly a little over one-fourth. I have some statistics which I can find for you in terms of active women on the Executive Committees, etc. Those percentages are going up. But at any rate, I think that the Women’s Outreach effort has an aspect of being a kind of support group for women within the Sierra Club.” pgs 3–4

- For ten years, Doris Cellarius chaired the Club’s Hazardous Waste Advisory Committee. In 2001, she recalled when younger that, “I didn’t feel any need to go out and arm myself as a militant feminist. … I was busy, and I have very little experience with women who had problems … But I really began to feel it when I worked with these women at toxic waste sites and saw that it was mostly women. I saw how the people from the agencies were mostly men, and they didn’t take the women too seriously. It never made me feel it was a gender thing, though; I thought it was more government oppressing the citizens and treating them like something in the way of getting their job done.” pg 63

- In 1979, amid national efforts to secure an Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Helen Burke declared, “The more men see capable women, qualified women elected to the Board [of Directors], the more they will see that women are able to carry significant burdens, etc. That’s what women’s liberation is all about.” pg 15

More work remains, both for women in the Sierra Club and on this oral history research project. I plan to continue this research next semester to comb through more Sierra Club interviews and further compile an annotated outline of themes and examples. My goal is to organize this rich archive of Sierra Club women’s oral histories so future scholars and interested people can better understand the Club’s growth—in size and especially in scope—through the narratives of its female members.

— Ella Griffth, UC Berkeley, Class of 2020