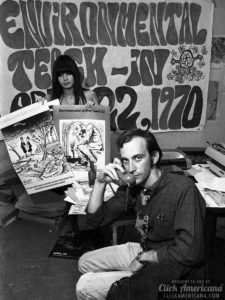

Earth Day turns 50 this month. A half-century ago, on April 22, 1970, environmental awareness and concern exploded in a nationwide outpouring of celebrations and protests during the world’s first Earth Day. That first Earth Day drew an estimated twenty million participants across the United States—roughly a tenth of the national population—with involvement from over ten thousand schools and two thousand colleges and universities. Earth Day on April 22, 1970, became the then-largest single-day public protest in U.S. history. The actual numbers of participants were even higher, as several universities, notably the University of Michigan, held massive Earth Day teach-ins during the weeks before April 22 to avoid overlapping with their final exams. From New York City to San Francisco, from Birmingham to Ann Arbor—millions of Americans gathered on campuses, met in classrooms, visited parks and public lands together, participated in local clean-ups, and marched in the streets for greater environmental awareness and to demand greater environmental protections. Even Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, who in the fall of 1969 promoted the idea for nation-wide Earth Day teach-ins, was surprised, calling the occasion a “truly astonishing grass-roots explosion.” And over the ensuing fifty-years since 1970, Earth Day events have spread globally to over 193 countries, making it the world’s largest secular holiday celebrated by more than a billion people each year.

But this April, despite years of planning for Earth Day’s fiftieth anniversary, the novel coronavirus—itself a world-wide environmental event—has disrupted Earth Day 2020 plans across the planet. While we cannot celebrate Earth Day’s golden anniversary as previously planned, we can commemorate it with recollections and lessons learned by those who attended and organized the first Earth Day events in 1970. The Oral History Center’s archives list over seventy interviews that mention Earth Day, according to the “Advanced Search” fields of our collection’s search engine. I’ve selected here a few memories of the first Earth Day from our Sierra Club Oral History Project, a longstanding collaboration between the Oral History Center and the Sierra Club, which itself originated shortly after the first Earth Day. These Earth Day memories shared by Sierra Club members begin with experiences in the streets of New York City, they include memories at the forefront of environmental law, and they conclude with events at the University of Michigan during the first-ever Earth Day teach-in.

But this April, despite years of planning for Earth Day’s fiftieth anniversary, the novel coronavirus—itself a world-wide environmental event—has disrupted Earth Day 2020 plans across the planet. While we cannot celebrate Earth Day’s golden anniversary as previously planned, we can commemorate it with recollections and lessons learned by those who attended and organized the first Earth Day events in 1970. The Oral History Center’s archives list over seventy interviews that mention Earth Day, according to the “Advanced Search” fields of our collection’s search engine. I’ve selected here a few memories of the first Earth Day from our Sierra Club Oral History Project, a longstanding collaboration between the Oral History Center and the Sierra Club, which itself originated shortly after the first Earth Day. These Earth Day memories shared by Sierra Club members begin with experiences in the streets of New York City, they include memories at the forefront of environmental law, and they conclude with events at the University of Michigan during the first-ever Earth Day teach-in.

We begin with Michele Perrault, a future two-time president of the Sierra Club, who in 1970 lived and worked in New York City as an elementary science educator. New York City was the site the nation’s largest celebration of Earth Day, which garnered nationwide media attention given that NBC, CBS, ABC, The New York Times, Time, and Newsweek were all headquartered in Manhattan. Perrault, then twenty-eight years old, taught in the demonstration school at the Bank Street College of Education, founded in 1916 by Lucy Sprague Mitchell, a child education reformer and, earlier, Berkeley’s first Dean of Women. For her part, Perrault shared during her oral history how she organized “a Bank Street program out in the street for Earth Day in New York City.” Perrault recalled, “we had our own booth, and I had the kids there … Mostly we sang songs and danced around and had some visuals and books that people could read or get, and we had some pamphlets from the [Bank Street] college that talked about it.” In the process, Perrault and her students joined hundreds of thousands other Earth Day participants in the streets of Manhattan. John Lindsay, the Republican mayor of New York, had closed traffic on Fifth Avenue for Earth Day and made Central Park available for gigantic crowds to march and celebrate together. In Union Square, crowds of 20,000 people gathered at any given time, with the New York Times estimating over 100,000 people visiting Union Square throughout the day.

and Newsweek were all headquartered in Manhattan. Perrault, then twenty-eight years old, taught in the demonstration school at the Bank Street College of Education, founded in 1916 by Lucy Sprague Mitchell, a child education reformer and, earlier, Berkeley’s first Dean of Women. For her part, Perrault shared during her oral history how she organized “a Bank Street program out in the street for Earth Day in New York City.” Perrault recalled, “we had our own booth, and I had the kids there … Mostly we sang songs and danced around and had some visuals and books that people could read or get, and we had some pamphlets from the [Bank Street] college that talked about it.” In the process, Perrault and her students joined hundreds of thousands other Earth Day participants in the streets of Manhattan. John Lindsay, the Republican mayor of New York, had closed traffic on Fifth Avenue for Earth Day and made Central Park available for gigantic crowds to march and celebrate together. In Union Square, crowds of 20,000 people gathered at any given time, with the New York Times estimating over 100,000 people visiting Union Square throughout the day.

Earlier that month, at a meeting of student teachers involved in planning Earth Day teach-ins in New York, Perrault met René Dubos, famed microbiologist and Pulitzer-Prize-winning author credited with coining the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally.” Perrault, in her role as education chair of the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter, was then producing a monthly newsletter for environmental educators called Right Now, in which she  recalled what Dubos emphasized for Earth Day. Dubos had “stressed the importance and need for people to take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives perhaps not in existence now, to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” Perrault added that “We, as teachers, need to ask new questions about our own values, about our own social and economic systems and their relationship to the environment, so as to enrich the present and potential environment for children.” (Two copies of Right Now are included in the appendix to Perrault’s oral history.) Less than a year after Earth Day, Perrault then organized at Bank Street College an education conference on “Environment and Children” and invited Dubos as the keynote speaker. Perrault recalled Dubos calling for stimulating environments for children that offered “the ability to choose, to have variety, to not just be in one place where everything was static around them and where they weren’t in control. [He] had a big paper on this whole issue of free will and being able to make choices, and how the environment would influence them.” Years later, after moving to California, Perrault took her own children on annual backpacking trips deep into the High Sierra where they could run wild and free, stimulated by natural wilderness.

recalled what Dubos emphasized for Earth Day. Dubos had “stressed the importance and need for people to take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives perhaps not in existence now, to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” Perrault added that “We, as teachers, need to ask new questions about our own values, about our own social and economic systems and their relationship to the environment, so as to enrich the present and potential environment for children.” (Two copies of Right Now are included in the appendix to Perrault’s oral history.) Less than a year after Earth Day, Perrault then organized at Bank Street College an education conference on “Environment and Children” and invited Dubos as the keynote speaker. Perrault recalled Dubos calling for stimulating environments for children that offered “the ability to choose, to have variety, to not just be in one place where everything was static around them and where they weren’t in control. [He] had a big paper on this whole issue of free will and being able to make choices, and how the environment would influence them.” Years later, after moving to California, Perrault took her own children on annual backpacking trips deep into the High Sierra where they could run wild and free, stimulated by natural wilderness.

Perrault was recruited to the Sierra Club shortly before Earth Day by David Sive, a pioneer of environmental law in New York, whose children Perrault taught in her science classroom. Another Sierra Club member and trailblazer of environmental law, James Moorman, shared his own memories of the first Earth Day in his oral history. By 1970, Moorman had joined the recently created Center for Law and Social Policy in Washington, DC, an influential public-interest law firm. As a young trial lawyer in the late 1960s, Moorman brought two cases that became landmarks in environmental law, including a petition to the Department of Agriculture to de-register the pesticide DDT, as well as a suit challenging construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. For the pipeline case, Moorman pioneered use of the National  Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), enacted in January 1970, to demand from the Department of Interior a detailed environmental impact statement for the construction project. Moorman recalled how “the preliminary injunction hearing for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was originally set for Earth Day. The hearing got postponed. It didn’t occur for another two weeks. But when the judge first set the hearing, I said, ‘Holy cow! He set the hearing for this on Earth Day and he doesn’t know it, and the oil companies don’t know it. I’m going to get to make my argument on Earth Day. That’s fantastic!’ But then there was a postponement, and the argument didn’t occur until two weeks later. But it was wonderful anyway.” Moorman won his case, but Congress directly intervened to approve the pipeline by law. Nonetheless, Moorman’s injunction forced the oil companies to spend three more years and a small fortune on engineering, analysis, and documentation. The final environmental impact statement for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline stretched to nine volumes. Moorman’s intervention helped produce a safer pipeline that is still considered a wonder of engineering.

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), enacted in January 1970, to demand from the Department of Interior a detailed environmental impact statement for the construction project. Moorman recalled how “the preliminary injunction hearing for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was originally set for Earth Day. The hearing got postponed. It didn’t occur for another two weeks. But when the judge first set the hearing, I said, ‘Holy cow! He set the hearing for this on Earth Day and he doesn’t know it, and the oil companies don’t know it. I’m going to get to make my argument on Earth Day. That’s fantastic!’ But then there was a postponement, and the argument didn’t occur until two weeks later. But it was wonderful anyway.” Moorman won his case, but Congress directly intervened to approve the pipeline by law. Nonetheless, Moorman’s injunction forced the oil companies to spend three more years and a small fortune on engineering, analysis, and documentation. The final environmental impact statement for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline stretched to nine volumes. Moorman’s intervention helped produce a safer pipeline that is still considered a wonder of engineering.

In the year following the first Earth Day, Moorman accepted a new job as the founding Executive Director of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (SCLDF), now called Earthjustice, one of the nation’s earliest and most influential public-interest environmental law organizations. Moorman directed SCLDF through 1974 and he worked as a staff attorney with the organization through 1977, after which he became Assistant Attorney General for Land and Natural Resources during President Carter’s administration. In his 1984 oral history, Moorman reflected on the importance of Earth Day for environmental law: “The fact is Earth Day came rather early in all this [environmental law] movement. We’ve been living on the energy created by Earth Day ever since.” Mike McCloskey agreed.

In 1970, Mike McCloskey, also a lawyer, was still new in his role as Executive Director of the Sierra Club, a position he held through 1985. In his first of two oral histories, this one from 1981, McCloskey recalled the Earth-Day-era as  “a very exciting time in terms of developing new theories [of environmental law], and our spirits were charged up. The courts were anxious to make law in the field of the environment. There were judges who were reading, and they were stimulated by the prospect. They were eager to get environmental cases.” McCloskey continued, “what became clear over the next few years [after Earth Day] were that dozens of, if not hundreds, of laws were passed and agencies brought into existence.” Indeed, in the months and years following the first Earth Day, President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Congress passed a suite of landmark environmental statutes—including an amended Clean Air Act; the Clean Water Act; the Safe Drinking Water Act; the Endangered Species Act; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA); the Toxic Substances and Control Act (TSCA) and many others—all of which have, thus far, avoided extinction.

“a very exciting time in terms of developing new theories [of environmental law], and our spirits were charged up. The courts were anxious to make law in the field of the environment. There were judges who were reading, and they were stimulated by the prospect. They were eager to get environmental cases.” McCloskey continued, “what became clear over the next few years [after Earth Day] were that dozens of, if not hundreds, of laws were passed and agencies brought into existence.” Indeed, in the months and years following the first Earth Day, President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Congress passed a suite of landmark environmental statutes—including an amended Clean Air Act; the Clean Water Act; the Safe Drinking Water Act; the Endangered Species Act; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA); the Toxic Substances and Control Act (TSCA) and many others—all of which have, thus far, avoided extinction.

McCloskey described Earth Day 1970 as an explosion of environmental consciousness that had grown steadily throughout the late 1960s. In 1968, fellow conservationists thought the best of things has already happened with the creation of Redwood National Park in California, North Cascades National Park in Washington state, and passage of both the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails System Act, all in that year. McCloskey recalled, “We at the moment thought this was some high point in conservation history and wondered whether much would happen thereafter.” When President Nixon came into office in January 1969, McCloskey and other Sierra Club leaders “felt very defensive and threatened, not realizing that we were on a threshold of an explosion into a period of our greatest growth and influence.” Instead of a plateau or even a decline in environmental efforts, McCloskey and fellow Sierra Club leaders saw the American environmental movement  experience a “tremendous take-off in terms of the overall quantity of activity, enthusiasm, and support with Earth Day coming. … it was just an eruption of activity on every front.” But much to his surprise, with Earth Day in 1970, McCloskey also saw how many traditional leaders of the conservation movement were quickly “regarded as old hat and out of step with the times.” In their place, he witnessed how “people emerged at the student level, literally from nowhere, who were inventing new standards for what was right and what should be done and whole new theories overnight. For instance, I remember hostesses who were suddenly saying, ‘I can’t serve paper napkins anymore. I’ve got to have cloth napkins.’ Someone had written that paper napkins were terribly wrong, and colored toilet paper was regarded as a sin. But all sorts of people from different backgrounds coalesced in the environmental movement. People who were interested in public health suddenly emerged and very strongly.” One such person was Doris Cellarius.

experience a “tremendous take-off in terms of the overall quantity of activity, enthusiasm, and support with Earth Day coming. … it was just an eruption of activity on every front.” But much to his surprise, with Earth Day in 1970, McCloskey also saw how many traditional leaders of the conservation movement were quickly “regarded as old hat and out of step with the times.” In their place, he witnessed how “people emerged at the student level, literally from nowhere, who were inventing new standards for what was right and what should be done and whole new theories overnight. For instance, I remember hostesses who were suddenly saying, ‘I can’t serve paper napkins anymore. I’ve got to have cloth napkins.’ Someone had written that paper napkins were terribly wrong, and colored toilet paper was regarded as a sin. But all sorts of people from different backgrounds coalesced in the environmental movement. People who were interested in public health suddenly emerged and very strongly.” One such person was Doris Cellarius.

In 1970, Doris Cellarius lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with her children and husband, Richard (Dick) Cellarius, a professor of botany then teaching at the University of Michigan. According to Doris, she and Dick were both members of the Sierra Club in 1970, but mostly for hiking and social engagement, less for activism. The extraordinary events surrounding Earth Day in Ann Arbor changed everything. Doris explained, “Earth  Day came as a great shock to me because it had never occurred to me that the environment didn’t clean itself. I thought that water that flows along in a creek was purified by sunlight, and I guess I didn’t know a lot about where pollution came from. When I learned at the time of Earth Day how much pollution there was and how bad pesticides were, I instantly became very active in the pollution area of the environment.” In the wake of Earth Day, Doris Cellarius drew upon her master’s degree in biology from Columbia University to become a grassroots activist and environmental organizer, particularly against the use of pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Within the Sierra Club, she became head of several local and national committees focused on empowering people in campaigns for hazardous waste clean-up and solid waste management. In her oral history, Doris Cellarius reflected on the impetus behind her decades of environmental activism: “I learned at Earth Day there was pollution, so I think, having learned there was pollution, I decided that people should find out ways to stop creating that pollution.”

Day came as a great shock to me because it had never occurred to me that the environment didn’t clean itself. I thought that water that flows along in a creek was purified by sunlight, and I guess I didn’t know a lot about where pollution came from. When I learned at the time of Earth Day how much pollution there was and how bad pesticides were, I instantly became very active in the pollution area of the environment.” In the wake of Earth Day, Doris Cellarius drew upon her master’s degree in biology from Columbia University to become a grassroots activist and environmental organizer, particularly against the use of pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Within the Sierra Club, she became head of several local and national committees focused on empowering people in campaigns for hazardous waste clean-up and solid waste management. In her oral history, Doris Cellarius reflected on the impetus behind her decades of environmental activism: “I learned at Earth Day there was pollution, so I think, having learned there was pollution, I decided that people should find out ways to stop creating that pollution.”

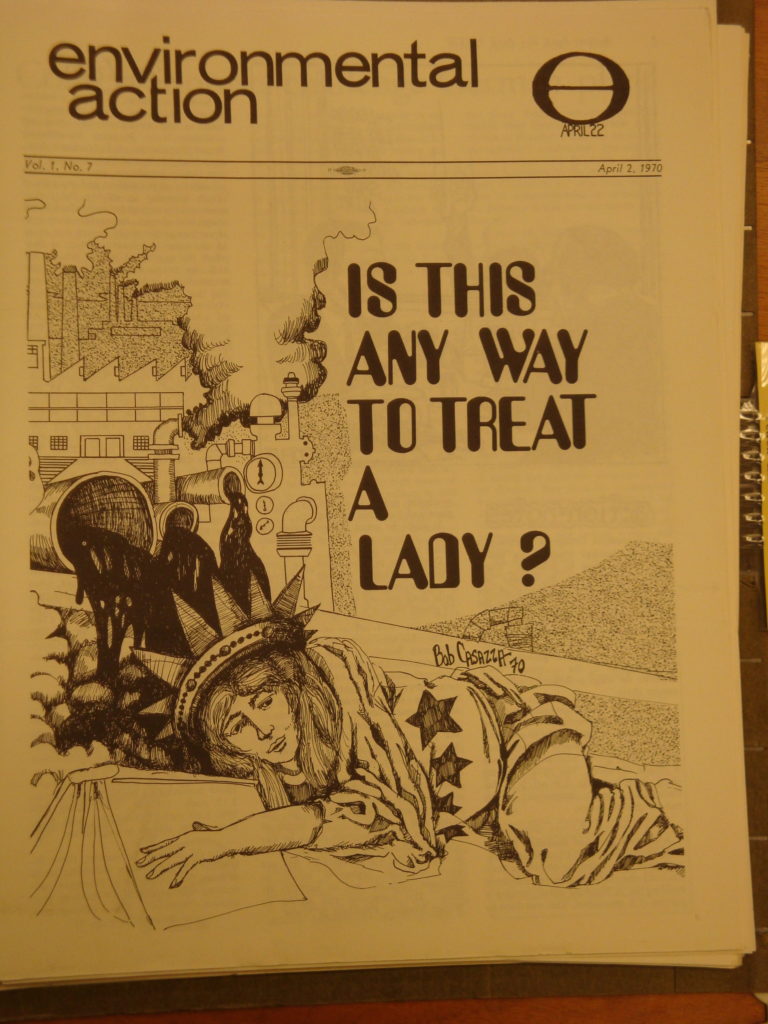

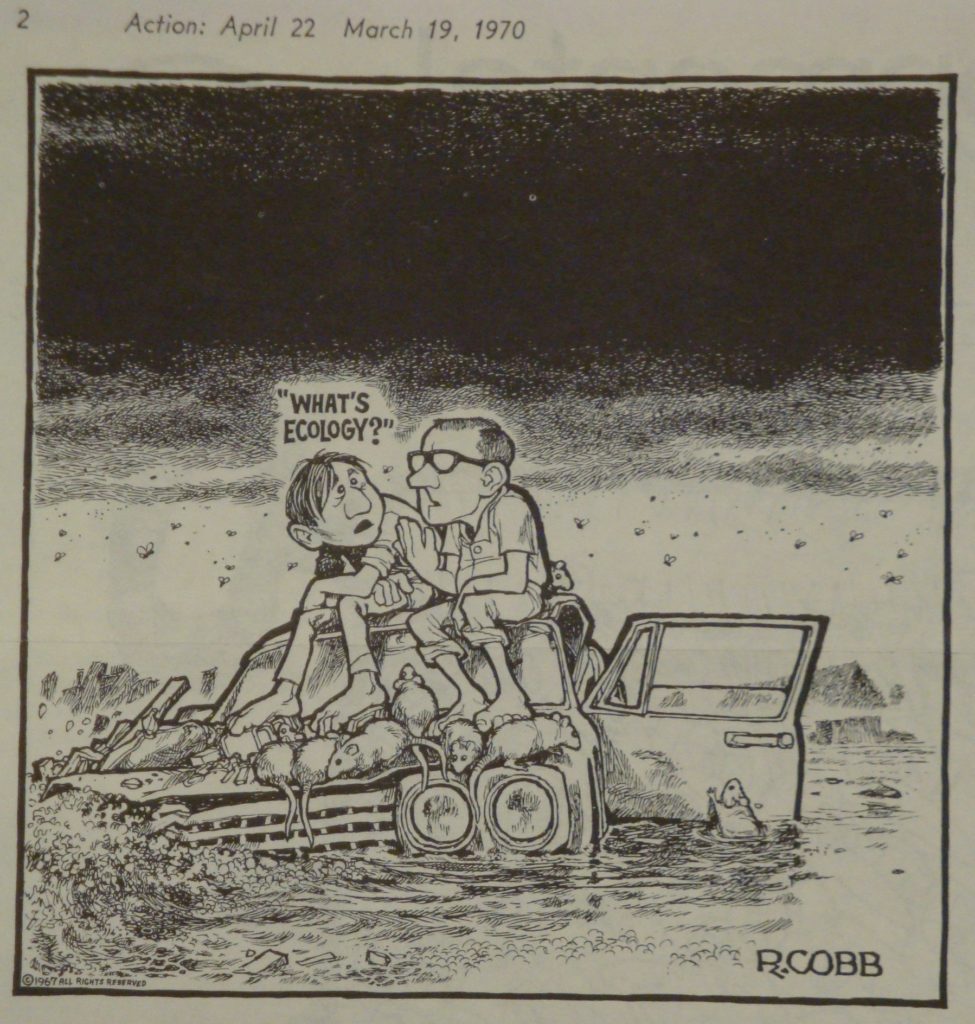

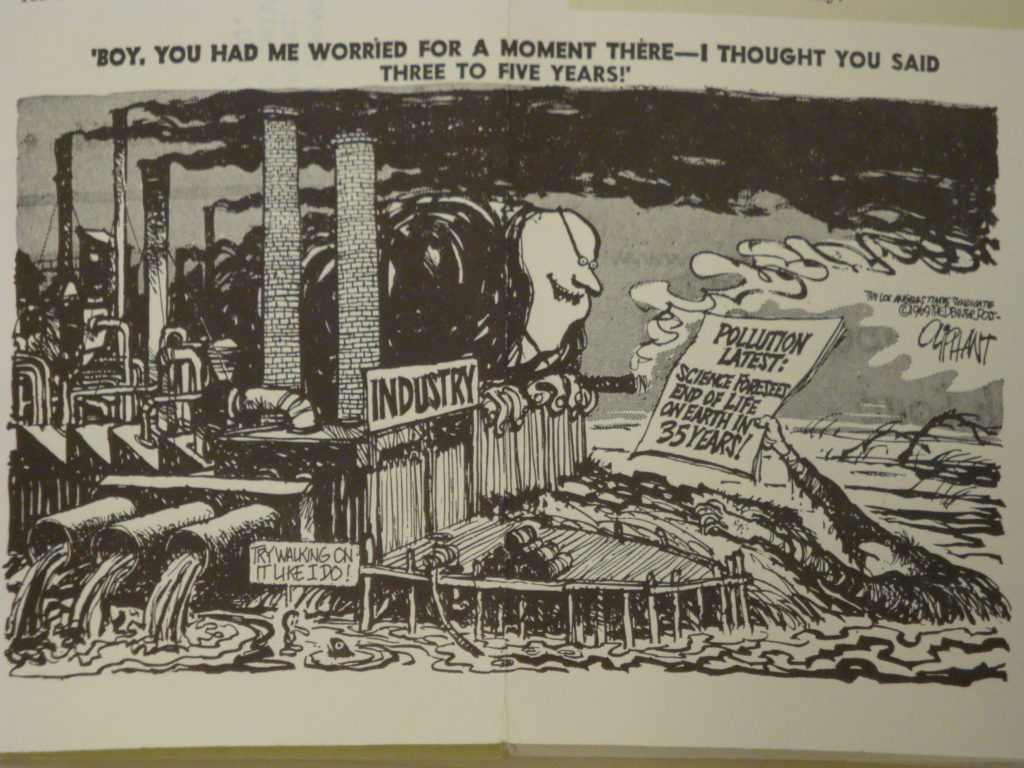

Fifty years ago, the dynamic events surrounding the first Earth Day reflected how environmental issues could rapidly mobilize new publics for radical reform and institutional action. Indeed, the small organization created to nationally coordinate the first Earth Day took the name Environmental Action. Denis Hayes, the then-twenty-five-year-old national coordinator for Environmental Action, announced on Earth Day, “We are building a movement … a movement that values people more than technology, people more than political boundaries and political ideologies, people more than profit.” This exuberance for a new kind of environmental movement, according to historian John McNeill, arose “in a context of countercultural critique of any and all established orthodoxies.” But, at its root, Earth Day—and the concomitant flowering of concern for Spaceship Earth and all travelers on it—constituted “a complaint against economic orthodoxy.” According to McNeil, “It was a critique of the faith of economists and engineers, and their programs to improve life on earth.” For new adherents to this ecological insight, the popularity of Earth Day’s events contributed collectively to “a general sense that things were out of whack and business as usual was responsible.” That all sounds terribly familiar today.

than political boundaries and political ideologies, people more than profit.” This exuberance for a new kind of environmental movement, according to historian John McNeill, arose “in a context of countercultural critique of any and all established orthodoxies.” But, at its root, Earth Day—and the concomitant flowering of concern for Spaceship Earth and all travelers on it—constituted “a complaint against economic orthodoxy.” According to McNeil, “It was a critique of the faith of economists and engineers, and their programs to improve life on earth.” For new adherents to this ecological insight, the popularity of Earth Day’s events contributed collectively to “a general sense that things were out of whack and business as usual was responsible.” That all sounds terribly familiar today.

This year, on the golden anniversary of Earth Day, life all across the planet is out of whack and business as usual has come to a sudden stop. From climate change to the novel coronavirus to the deteriorating condition of American politics, a slew of increasingly complex and interconnected problems affect us all. But perhaps, this moment—like the one in 1970—offers a unique opportunity to think how we might begin things anew. Perhaps, as René Dubos advised on the first Earth Day in April 1970, we in 2020 can “take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives … to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” May it be so. May you help make it so.