The following is a guest post from our summer 2015 intern Beaudry Allen, a graduate student in the Master of Archives and Records Administration (MARA) program at San Jose State University’s iSchool.

Case Study of the Digital Files from the Reginald H. Barrett Papers

As archivists, we have long been charged with selecting, appraising, preserving, and providing access to records, though as the digital landscape evolves there has been a paradigm shift in how to approach those foundational practices. How do we capture, organize, support long-term preservation, and ultimately provide access to digital content; especially with the convergence of challenges resulting from the exponential growth in the amount of born-digital material produced?

So, embarking on a born-digital processing project can be a daunting prospect. The complexity of the endeavor is unpredictable, and undoubtedly unforeseen issues will arise. This summer I had the opportunity to experience the challenges of born-digital processing firsthand at the Bancroft Library, as I worked on the digital files from the Reginald H. Barrett papers.

Reginald Barrett was a former professor at UC Berkeley in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, & Management. Upon his retirement in 2014, Barrett donated his research materials to the Bancroft Library. In addition to more than 96 linear feet of manuscripts and photographs (yet to be described), the collection included one hard drive, one 3.5” floppy disk, three CDs, and his academic email account. His digital files encompassed an array of emails, photographs, reports, presentations, and GIS-mapping data, which detailed his research interests in animal populations, landscape ecology, conservation biology, and vertebrate population ecology. The digital files provide a unique vantage point from which to examine the methods of research used by Barrett, especially his involvement with the development of California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System. The project’s aim was to process and describe Barrett’s born-digital materials for future access.

The first step in processing digital files is ensuring that your work does not disrupt the authenticity and integrity of the content (this means taking steps to prevent changes to file dates and timestamps or inadvertently rearranging files). Luckily, the initial ground work of virus-checking the original files and creating a disk image of the media had already been done by Bancroft Technical Services and the Library Systems Office. A disk image is essentially an exact copy of the original media which replicates the structure and contents of a storage device. Disk imaging was done using a FRED (Forensic Recovery of Evidence Device) workstation, and the disk image was transferred to a separate network server. The email account had also been downloaded as a Microsoft Outlook .PST file and converted to the preservation MBOX format. Once these preservation files were saved, I used a working copy of the files to perform my analysis and description.

My next step was to run checksums on each disk image to validate its authenticity, and to generate file directory listings which will serve as inventories of the original source media. The file directory listings are saved with the preservation copies to create an AIP (Archival Information Package).

Using FTK

Actual processing of the disk images from the CDs, floppy disk, and hard drive was done using the Forensic Toolkit (FTK) software. The program reads disk images and mimics the file system and contents, allowing me to observe the organizational structure and content of each media. The processing procedures I used were designed by Kate Tasker and based on the 2013 OCLC report, “Walk This Way: Detailed Steps for Transferring Born-Digital Content from Media You Can Read In-house” (Barrera-Gomez & Erway, 2013).

Processing was a two-fold approach; one, survey the collection’s content, subject matter, and file formats; and two (which was a critical component to processing), identify and restrict items that contained Personally Identifiable information (PII), or student records protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). I relied on FTK’s pattern search function to locate Social Security Numbers, credit card numbers, phone numbers, etc., and on its index search function to locate items with sensitive keywords. I was then able to assign “restricted” labels to each item and exclude them from the publicly-accessible material.

While I, like many iSchool graduate students, am familiar with the preservation standard charts for file formats, I was introduced to new file formats and GIS data types which will require more research before they can be normalized to a format recommended for long-term preservation or access. Though admittedly hard, there is something gratifying about being faced with new challenges. Another challenge was identifying and flagging unallocated space, deleted files, corrupted files, and system files so they were not transferred to an access copy.

A large component of traditional archival processing is arrangement, yet creating an arrangement beyond the original order was impractical as there were over 300,000 files (195 GB) on the hard drive alone. Using original order also preserves the original file name convention and file hierarchy as determined by the creator. Overall, I found Forensic Toolkit to be a straightforward, albeit sensitive program, and I was easily able to navigate the files and survey content.

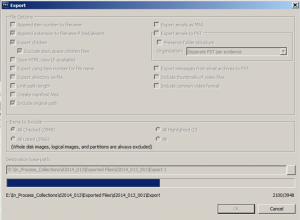

One of the challenges in using FTK which halted my momentum many times was exporting. After processing in FTK and assigning appropriate labels and restrictions, the collection files were exported with the restricted files excluded (thus creating a second, redacted AIP). The exported files would then be normalized to a format which is easy to access (for example, converting a Word .doc format to .pdf). The problem was the computer could not handle the 177 GB of files I wanted to export. I could not export directories larger than 20 GB without it either crashing or receiving export errors from FTK. This meant I needed to export some directories in smaller pieces, with sizes ranging from 2-15 GB. Smaller exports took ten minutes each, while larger files from 10-15 GB could take 4-15 hours, so most of my time was spent wishin’ and hopin’ and thinkin’ and prayin’ the progress bar for each export would be fast.

Another major hiccup occurred in large exports, when FTK failed to exclude files marked as restricted. This meant I had go through the exported files and cross reference my filters so I could manually remove the restricted items. By the end of it, I felt like I did all the work twice, but the experience helped us to determine the parameters of what FTK and the computer could handle.

The dreaded progress bar…

Using ePADD

The email account was processed using an open-source program developed by Stanford University’s Special Collections & Archives that supports the appraisal, processing, discovery, and delivery of email archives (ePADD). Like FTK, ePADD has the ability to browse all files and add restrictions to protect private and sensitive information. I was able to review the senders and message contents, and display interesting chart visualizations of the data. Considering Barrett’s email was from his academic account, I had run “lexicon” searches relating to students to find and restrict information protected by FERPA. ePADD allows the user to choose from existing or user-generated lexicons, in order to search for personal or confidential information, or to perform complex searches for thematic content. I had better luck entering my own search terms to locate specific PII than accepting ePADD’s default search terms, as I was very familiar with the collection by that point and knew what kind of information to search for.

For the most part the platform seems very sleek and user-friendly, though I had to refer to the manual more often than not as I ended up not finding the interface as intuitive as it seemed. After appraisal and processing, ePADD will export the emails to the discovery or delivery modules. The delivery module provides a user interface so researchers can view the emails. The Bancroft Library is in the process of implementing plans to make email collections and other born-digital materials available.

Overall, the project was also a personal opportunity to evaluate the cyclical relationship between theory and practice of digital forensics and processing. Before the project I had a good grasp on the theoretical requirements and practices in digital preservation, but had not conceptualized the implications of each step of the project and how time-consuming it could be. The digital age conjures up images of speed, but I spent 100 hours (in a 7-week period) processing the collection. There are so many variables that need to be considered at each step, so that important information is made accessible. This also amplified the need for collaboration in building a successful digital collection program, as one must rely on participation from curatorial staff and technical services to ensure long-term preservation and access. The project even brought up new questions of “More Product, Less Process” (MPLP) processing in relation to born-digital content: what are the risks associated with born-digital MPLP, and how can an institute mitigate potential pitfalls? How do we need to approach born-digital processing differently?