Tag: Chinese American history

“‘Rice All the Time?’: Chinese Americans in the Bay Area in the Early 20th Century”

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

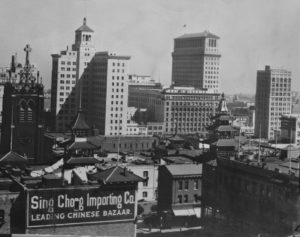

The Bay Area is home to San Francisco Chinatown, the first Chinatown in the United States. By the 1900s, there were second- and third-generation Chinese Americans living here who had spent their entire lives in the US. Interviews in the Oral History Center illuminate the experiences of these Chinese Americans who grew up in the Bay Area, and not just in Chinatown. What were the daily lives like of Chinese American youths living in Berkeley, or Emeryville, in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s? This is “Rice All the Time?”, an oral history performance about their experiences, brought to you in an audio format and performed by five young Chinese Americans.

This episode focuses on the experiences of one ethnic group. While we discuss Chinese American experiences with identity and discrimination, we recognize that this is just one part of a broad history of people of color in the United States. The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people, have made it even more evident that systemic bigotry is far from being a relic of history. We hope that after listening, you will engage in further conversation about racism in our nation and the complex experiences of people of color who live in the United States.

“Rice All the Time?” features direct quotes from interviews with Royce Ong, Alfred Soo, Maggie Gee, Theodore B. Lee, Dorothy Eng, Thomas W. Chinn, Young Oy Bo Lee, and Doris Shoong Lee. They describe their experiences with racial discrimination, through schoolyard bullying and housing exclusion. Some describe Chinese food with fondness, some with disdain. You will hear about after-school Chinese classes and the presence, or lack of, a local Chinese community.

This is a culmination of work I began in the fall of 2019 – I wrote a blog post about the process of creating the script.

While creating this performance, I related to some of their experiences, and was also surprised to hear many of them. It’s made me reflect on my conception of Chinese American history and my own identity as a Chinese American. I hope that “Rice All the Time?” fosters similar introspection in you.

Performed by Maggie Deng, Deborah Qu, Lauren Pong, and Diane Chao. Written and produced by Miranda Jiang. Editing and sound design by Shanna Farrell.

Cantonese readings of Young Oy Bo Lee’s lines accompany the English to reflect the original language of her interview.

Transcript:

Audio: (music)

Shanna Farrell: Hello and welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we’re in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we at the Oral History Center are in need of a break.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and find small moments of happiness.

Audio: (quotes spoken by performers, layered over each other)

(music)

Miranda Jiang: Hi, I’m Miranda Jiang, a history undergrad at UC Berkeley. You’re about to listen to an oral history performance I created called “‘Rice All the Time?’: Chinese Americans in the Bay Area in the Early 20th Century.” I originally intended for “‘Rice All the Time?” to be performed by a few of my fellow students in front of a live audience. But, of course, because of COVID-19 cancellations, we’re now bringing you this performance in an audio format.

“Rice All the Time?” presents perspectives of multiple Chinese people growing up in the Bay Area in the early 20th century. It places their words into conversation with each other, and it invites you, as listeners, to interpret them.

Before we get to the performance, I’d like to share with you a little background on the history of Chinese people in California.

Chinese immigration to the United States began in the mid-19th century. Thousands came to California as forty-niners during the Gold Rush. Racial resentment among white settlers in the West led to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred the immigration of Chinese laborers to the US. The Act slowed the entrance of Chinese men, and denied entrance to virtually all women except those married to merchants.

Chinese immigration continued despite the Exclusion Act, which was only repealed in 1943, along with other anti-Chinese regulations. The number of Chinese women in the US increased steadily after 1900. Chinese Americans in the Bay Area and elsewhere built vibrant communities.

This performance is made of direct quotes from oral histories in the archival collection of the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, here at UC Berkeley. It features the experiences of eight Chinese Americans who lived in the Bay Area from the 1920s to the 1950s. All, except one, were second or third-generation Chinese Americans who had spent all of their lives in the US. Alongside each other, these stories reveal a rich history and diversity of experiences within one ethnic group.

While you’re listening, I have some questions for you to keep in mind.

Think about what you know now of the Chinese American community in the Bay Area. Does hearing these experiences change your perception of their history? If so, how? What can their experiences with discrimination and identity teach us now, during the time of coronavirus and particularly visible racism against Asian people? How do you relate to these stories, many from almost a century ago?

After listening, I want to hear your feedback! Whether they’re answers to the questions I posed or other thoughts, please take a few minutes to fill out the Google form in the show notes. I appreciate any comments you may have, because your feedback will be super helpful to an article I’m working on about this project.

Now, please sit back and enjoy this performance of “Rice All the Time?”

Audio: (music)

Royce Ong (spoken by Diane Chao): There was not another Chinese family in Point Richmond, even a café or anything. Outside of my own relatives, I never had seen another Chinese.

Alfred Soo (spoken by Deborah Qu): … living in Berkeley, there weren’t very many Asians in my area. The Asians living in that area were probably my cousins.

Maggie Gee (spoken by Maggie Deng): It was before the onset of the war that brought in lots of people from elsewheres. Berkeley was integrated, in that sense… There were blacks, whites living in the neighborhood, quite a few Japanese, and some Chinese. More Japanese in my neighborhood than Chinese.

Theodore Lee (spoken by Lauren Pong): We didn’t know any Chinese. We lived in a neighborhood where we were the only Chinese. I went to a school where my family was the only Chinese in the school…

Dorothy Eng (spoken by Maggie Deng): [In Emeryville] there were three families, all Cantonese… It was an all white town. All [my mother] had was me, her children, and her husband whom she hardly knew.

Soo: … fortunately I didn’t experience any [teasing] that I can recall.

Eng: My father was very protective because he had seen the meanness to the Chinese, how they were treated, and he wanted to protect us because we were in a white community.

Theodore Lee: I wasn’t treated any differently because, remember now, these are people who are not snobby people; they’re working-class white, who tend, on the whole, to be friendly people. They’re not overly secure. There’s no snobbery. There’s no snobbery in our neighborhood. There was none.

Eng: … when I was in grammar school I hated it because I was never included, never included. All the years at grammar school I was not included in the classroom, I was not included in the playground. I can remember seeing myself going out during playtime, and I would be just standing there practically invisible. If I would go over to the rings because nobody else was there and start to swing, they would come and gather and push me off. The teachers were not there for you, the kids were just mean to you.

Audio: (sounds of children on a playground)

(music)

Ong: I think it was the Exclusion Act that didn’t allow the Asians to own property…“Asian” especially meant “Chinese…” The Exclusion Act had stopped them from immigrating and stopped them from owning property in the United States, especially California. I think they had their own law that was a little [more] stringent than the United States’ law. They were even segregated in the schools, when you read history.

Gee: I’ve lived around town in Berkeley, and Berkeley was a very difficult town to rent in, for non- whites … We really couldn’t find a place to live [there], because there would be a place available but when we came to see them, the place was rented. It became very discouraging… I sort of gave up. My sister, she’d call ahead of time and say that she was Chinese.

Thomas W. Chinn (spoken by Deborah Qu): We found out when we moved to San Francisco that the only place we could live in was Chinatown, because no one would rent to us or sell us a home outside of Chinatown.

Gee: I was hurt, more than anything else. Many years later I served on a commission on housing discrimination in the city of Berkeley. This was actually before the Rumford bill, and that was in the sixties. You’d think Berkeley, being a university city it’s an enlightened thing –– it’s just like any other city, though. People are frightened. If you allow a minority person to live [there], it would allow all the rest of the other minorities in. It’s really quite stupid… Yes, I was really disappointed in Berkeley.

Chinn: It was not a force of law; it was by word of mouth … no one wanted neighbors whose culture they did not understand or who could not speak to them in their own language.

Audio: (music)

Eng: When we moved to Oakland Chinatown I realized how different our family was from people I met in the church. Culturally, we were very different because we were brought up as a Christian family. We celebrated Christmas, Easter, 4th of July, all of the American holidays, also Thanksgiving. People in Chinatown did not celebrate these holidays. They celebrated the Chinese holidays, a big difference. When I joined the church, I realized this. They were all very curious about me because I was so different.

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong): “旧金山的唐人街是 一个很好的社区。有好多山,好多缆车。又有中国餐馆、店铺、银行、医院…你需要的都有”

Young Oy Bo Lee (spoken by Miranda Jiang): San Francisco’s Chinatown was a nice community within a nice city. There were a lot of hills and cable cars. There were Chinese restaurants, shops, banks, hospitals and just about any kind of shop you would want. Also, Cantonese was the main dialect spoken so it felt comfortable. There were modern conveniences in all the houses. All of these things made the adjustment to the new country easier. Chinatown was a haven for the Chinese immigrant.

Audio: (sounds of Chinatown, erhu playing)

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong) : 大部分人讲广东话,所以感觉好好。现代化的房屋,先进的设备,舒适的生活环境,新移民很容易过上新的生活

Doris Shoong Lee (spoken by Lauren Pong): At this time everyone in this area spoke Cantonese because most of the people in this area came from Guangdong. That is the one province in China that speaks Cantonese. So San Francisco Chinatown was all Cantonese speaking. It’s only been in the last maybe twenty, thirty years, since there has been a large influx of Chinese from other areas of China, that Mandarin is now spoken fairly commonly.

Chinn: My family hired some Chinese men to teach us how to write and speak Chinese, and how to read. But after spending all day in an American school, and then trying to revert back to a strange language that as children we never knew except for a few words from our parents, it was very hard. We were very poor Chinese scholars. That was one of the deciding factors for my parents––”Our children are getting too Americanized; they have no Chinese friends, they have no Chinese background. We think maybe we’d better move them back to San Francisco where they can live in Chinatown and learn more about their Chinese culture.”

Shoong Lee: I guess at that time there weren’t too many Chinese families that ventured and lived outside of Chinatown… San Francisco Chinatown has always been the very established community. But Oakland Chinatown at that time was rather small. Now it is quite different. It’s large.

Audio: (music)

Soo: I went to Chinese school in Oakland. So we’d take the streetcar to Oakland… In Chinatown. And we’d get there and start at 5:00 and start home at 8:00. That’s a long day.

Audio: (sound of streetcar and bell ring)

Shoong Lee: My dad wanted us to learn Chinese from the time we were in school. So we had tutors all the way through high school, my sister and I. The tutor came in five afternoons a week from four to six and Saturday mornings from ten to twelve…That’s a lot of Chinese…

Gee: When I was young, we used to have a teacher come to our house. It was really for my brother… to know Chinese. The girls got a little bit of Chinese…There used to be a name –– I forget what the word is, a very derogatory name for people who did not speak Chinese in the Chinese community. As I grew up, my mother was ashamed, a little bit. [laughs] Not really, though, but you know, people would always mention “Your children don’t speak Chinese.”

Ong: My mother knew English, but she always wanted to speak Cantonese, but I didn’t. I always answered in English, made her mad.

Gee: … with my generation, you didn’t want to speak Chinese, because you wanted to integrate. Didn’t want to eat with chopsticks, none of that. “Why are we having rice all the time?

Shoong Lee: I always loved my Chinese food… Sundays were always noodles at lunchtime. Those wonderful noodles. I can remember from the time I was maybe eleven, twelve, thirteen, on up, was that Sundays was when the New York Philharmonic came on the air. It was radio at that time, no television. Three o’clock in New York was lunch time in San Francisco. My sister and I would sit on the steps and have our lunch and listen to the New York Philharmonic.

Audio: (music, “Rhapsody in Blue”)

Ong: My mother cooked Chinese food and American food, but I don’t. I just eat regular American food.

Shoong Lee: We had Chinese meals for dinner but western breakfasts and lunch if we were home on the weekends. But dinner was always Chinese food. One of the things that Dad always wanted us to do was be able to name every dish that was on the table at night, and to speak Chinese at the dinner table.

Audio: (music, “Rhapsody in Blue”)

Chinn: We want to produce the concept of a Chinese-American who is striving hard to let people know that the Chinese part of a Chinese-American is something the Chinese are proud of, but at the same time they want to be known more as Americans.

Young Oy Bo Lee: I’m afraid the younger generation won’t understand this –– but holding on to traditions and customs is holding on to part of one’s identity. I hope that more of our young people will try to hold on to their Chinese identity and heritage.

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong): 年轻一代不理解这 一点 —

保持传统同习俗,是坚持自己身份的一部分。我希望更多的年轻人会继续保持自己华人的身份同传统。

Chinn: I think if you are born a Chinese, sooner or later you come to appreciate the background and the culture of things Chinese. I know that among our friends, all our children that are growing up do not have that much interest in Chinese culture, but as they approach middle age and thereafter, then they pick up and want to learn more about their language and background.

Audio: (music)

Jiang: Thank you so much for listening to this oral history performance. I hope that it sparks your interest in the full interviews with each individual featured in the podcast. Many of these interviews include videos in addition to a printed transcript, and you can easily access them through the Oral History Center website and in the show notes.

Audio: (music)

Jiang: I’d like to thank our performers, Maggie Deng, Deborah Qu, Lauren Pong, and Diane Chao, for their wonderful work. I thank my mentors, Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor for making this episode come to fruition. Thanks so much to Shanna Farrell for being our editor and sound designer. And thank you to the people whose interviews were featured in this performance: Royce Ong, Alfred Soo, Maggie Gee, Theodore B. Lee, Dorothy Eng, Thomas W. Chinn, Young Oy Bo Lee, and Doris Shoong Lee.

Once again, don’t forget to send your reactions to this episode! I want to hear your thoughts, however long. There’s a link to a Google form in the show notes that includes a few questions about your listening experience.

Thank you for listening to “‘Rice All the Time?” I hope you enjoyed the performance and that you have a wonderful rest of your day.

Audio: (music)

Farrell: Thanks for listening to The Berkeley Remix. We’ll catch up with you next time. And in the meantime, from all of us here at the Oral History Center, we wish you our best.

Chinese-American Identity and Oral History Performance: Rewriting the Script

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

In the fall of 2019, I joined an undergraduate research apprenticeship on oral history performance with Oral History Center interviewers Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor. Though I’d had some previous experiences with oral history, I wasn’t entirely sure what oral history performance was. I had my speculations: I was familiar with The Laramie Project and some other full-length plays which drew from oral histories. But no matter what the form of the performance would be, I understood that the project would take an approach to history that prioritized and shared the voices of ordinary people.

During the first few weeks of the semester, we discussed readings that fleshed out my understanding of oral history, then introduced me to multiple forms of oral history performance. Through readings such as Lynn Abrams’s Oral History Theory and Natalie Fousekis’s “Experiencing History: A Journey from Oral History to Performance,” I learned that the process of creating an oral history involves both the interviewer and the narrator (the person being interviewed). An oral history is a conversation. Both participants contribute to the content and direction of an oral history, and thus how an experience gets told. Oral history performance presents these experiences to the public, and places the experiences of multiple narrators in conversation with each other.

With these readings and assignments in mind, I searched through the Oral History Center’s vast archive of interviews to find sources for my own oral history performance. The only criteria I initially had in mind were that the subject I chose should be a story I knew little about, that I felt was undertold, and was centered in the Bay Area. I read interviews from the Freedom to Marry Project and the Suffragists Oral History Project, ultimately deciding on the Rosie the Riveter Project. It included interviews from people of African American, Chinese, Japanese, indigenous, and other backgrounds, and it was centered around the Bay Area.

I eventually decided to focus this performance on Chinese-American experiences in the Bay Area. I hoped that by focusing on this one group, I could have more time to flesh out the details of their lives. I do not have my own living grandparents to speak to, so hearing these stories about what young Chinese-American people like me had experienced growing up in California in the 1920s to 1950s made me feel connected to people who lived nearly a century ago. Hearing them also made me realize just how varied our experiences were.

Over the next weeks, I compiled a large annotated bibliography of quotes from relevant interviews, highlighting themes which continuously reemerged. In the spring semester, Amanda, Roger, and I shared many conversations about what it means to create a cohesive script out of direct quotes from oral histories. When we chose which quotes to group together, which to place in conversation with each other, and how we ordered and extracted quotes, we were interpreting each quote’s meaning. We constantly thought about how to assemble a script that highlighted common themes in the experiences of Chinese Americans, without taking narrators’ words out of context or imposing our own interpretations onto the quotes and our audience.

I soon found that by placing quotes of similar subjects next to each other, meaningful similarities and contrasts revealed themselves on their own. For example, many of the interviewers asked if the narrators had experienced teasing as children. Alfred Soo, Dorothy Eng, and Theodore Lee all described growing up in neighborhoods where they were among the only Chinese people there. Soo, who grew up in Berkeley in the 1920s, did not recall any teasing from other children. Lee, who grew up in the 1930s in Stockton, described not being treated any differently, emphasizing the lack of “snobbery” among working-class white people. Eng, who grew up in Emeryville in the 1920s, described being persistently mistreated by kids and teachers throughout grammar school. As a Chinese American who encountered racial insensitivity in school in the early 2000s, I expected that stories of children who grew up in the “age of exclusion” (1882-1943) would easily reinforce my own experiences. And yet, these oral histories showed a more complicated reality than I anticipated.

Another primary goal of this performance is to point the general public towards reading the full transcripts of the interviews. In the final script, there is a quote from Royce Ong, who states that he “just [eats] regular American food.” When I first read this, I was amused and annoyed by how he discounted Chinese food as something strange, when it was his own culture. But reading more of the interview, I found that his comments revealed more about his unique creation of a Chinese-American identity. He discussed “Chinese American” and “Chinese” as very distinct identities, with different political interests. To Ong, he could be a proud Chinese American as someone who didn’t eat Chinese food and who also learned only English as a first language.

Working on this performance made clear that no universal set of criteria comes with identifying as Chinese American. It made me aware of the vast multitude of experiences of other Chinese Americans, which are different from my own and different from each other. The format of the script brought the diversity of Chinese and American life to the forefront, and allowed each narrator to speak about their experiences as they occurred. It was up to the audience to observe and consider the contradictions between quotes.

The final script I created acknowledges that different Chinese Americans had unique experiences, while also highlighting similar struggles and activities within the ethnic group. Many anecdotes are relatable to me, today, and to other Chinese Americans in 2020. And ultimately, while some narrators leaned more towards embracing American culture, and others more towards also preserving Chinese traditions, all of them expressed the same conflicts with identity as Chinese people living in California.

By mid-March, we had created a final draft of the script after many sessions of cutting, rearranging, and reading out loud. We initially planned to give the eight-minute performance at the April 29th Oral History Commencement in the Morrison Library, with four or five student performers of Chinese-American backgrounds. When the campus closed due to COVID-19, we switched to an online podcast format, with the same script and number of performers.

The podcast version will be available on The Berkeley Remix this summer. I’m excited to be able to share this performance with more people using the magic of the Internet. I hope you’ll stay tuned for more!