In December 1904, American geographers gathered in Philadelphia to launch a new professional society, the Association of American Geographers (AAG). Geography was a new discipline in the United States. The first geography department had just been established one year earlier, at the University of Chicago. Up to this point, no forum existed for the regular exchange of ideas among professional geographers. The only publication devoted to the dissemination of scholarly geographical research was the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society.

The Association of American Geographers did not serve women geographers well: For much of its early history, the AAG organized male college and university geographers. Standard program features of AAG meetings, for example the prominent “smoker” social, made clear that the presence of women was not always welcome. At the 1915 annual meeting of the AAG, discussions of geographic education were cancelled altogether, to avoid both the topic and having “prim schoolmarms” at the smoker.

Only two women were among the 48 AAG charter members, Ellen Churchill Semple and Martha Krug-Genthe. Semple’s story is well documented, she has become a reference point in the pantheon of American geography, the representative pioneer woman geographer. In contrast, Krug-Genthe’s life has remained largely unexamined, in part because she was an immigrant woman and a sojourner who only spent a decade in the United States. Her professional endeavors are nevertheless illuminating:

Martha Krug-Genthe was the only one of the AAG founders in attendance in Philadelphia with a doctoral degree in geography. A recent transplant from Germany, Krug-Genthe had earned her doctorate at the University of Heidelberg in 1901 under the supervision of Alfred Hettner, a rising star in the profession. Martha’s dissertation examined how hydrographic charts had been used to map ocean currents. She analyzed the Gulf Stream and its northeastward extension, the North American Current, to map the expanding knowledge in the field of oceanography.

Martha Krug-Genthe and her spouse Karl Wilhelm Genthe represented something new, two young married research scientists who both insisted on pursuing professional careers. Karl had first arrived in the U.S. in 1897, after earning his Ph.D. in zoology at the University of Leipzig. In 1901, he transferred to Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and ultimately was appointed assistant professor of Natural History. With his professional future somewhat assured, Karl returned to Germany to marry Martha.

Initially, Martha was able to leverage her German credentials. In 1901, just after her arrival in the United States, National Geographic Magazine published her 14-page article surveying the German geography scene. She was able to gain a teaching position at Beacon School in Hartford, a secondary school for young women.

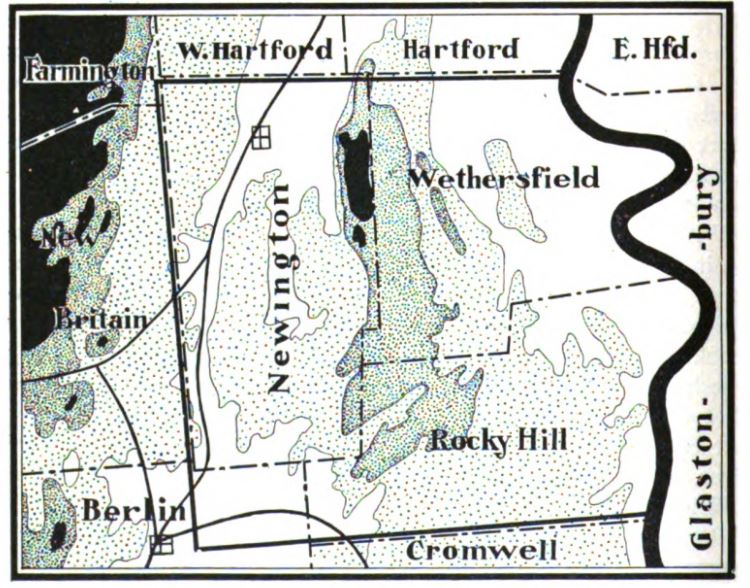

Connecticut’s geography emerged as a particular focus of Krug-Genthe’s research, the natural outgrowth of her work as a secondary school geography teacher. In 1907 the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society published her well-received Valley Towns of Connecticut, the work for which she is most remembered today.

Topography of Newington region, Connecticut River Valley, from Krug-Genthe’s Valley Towns of Connecticut.

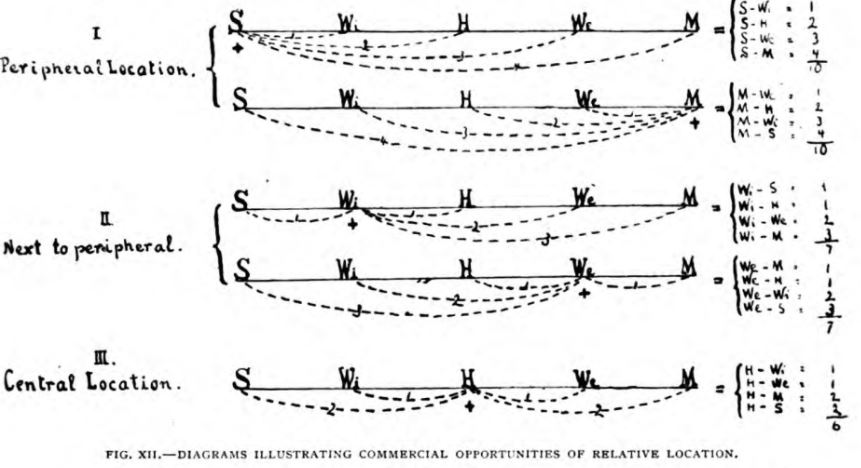

This was regional geography, a study of the economic factors driving the evolution of an urban system. Martha used historical sources but also location analysis to explain the rise of Hartford as the pre-eminent center of the Connecticut River Valley.

Location analysis diagram from Valley Towns of Connecticut, illustrating Krug-Genthe’s argument how its central location in the Connecticut River Valley favored Hartford (H).

In October 1903 Martha authored an article about geography textbooks for the Geography Teacher. This was the first of a long series of articles written by Krug-Genthe which discussed aspects of geography education in the United States and appeared in German and U.S. geography and science education journals.

The 1904 meeting of the International Geographical Congress Washington, D.C. was the high point of Martha Krug-Genthe’s professional career. Martha was selected to deliver the “Hommage,” an address commemorating Friedrich Ratzel, the pre-eminent cultural geographer of this time. She also presented a paper on “School geography in the United States” in the section on geography and education.

Issues of geographical education had historically been the one gateway open to women geographers who presented at International Geographical Congresses, beginning with a report by Clémence Royer at the Paris Congress in 1875. This was still true for the Washington Congress of 1904: Four of the five women listed in the congress program presented on pedagogical topics.

Martha Krug-Genthe was ultimately appointed associate editor of the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society. That affiliation bolstered her professional credentials, it was her one remaining secure foothold in the world of academic geography. Not surprisingly, the position appears in the author directory of the Encyclopedia Americana next to her name. It legitimized her role as expert.

But excluded from teaching positions at colleges and universities, Martha Krug-Genthe, just like other professional women geographers, increasingly relied on alternate professional networks which consisted of women geographers teaching at normal schools and secondary schools.

A large number of geography teachers in American secondary schools in the early 20th century were women. Professional women geographers were also well-represented among the geography instructors at the normal schools who trained these teachers. By the 1910s, normal schools hired more specialists in geography education, a process that gained momentum as the number and range of geography course offerings increased.

In 1917, shortly after the founding of the National Council of Geography Teachers, its membership roster boasted the names of 645 women, more than two-thirds of the organization’s members. The American Society of Professional Geographers likewise was able to recruit a larger number of women members.

So why did the AAG fail Martha Krug-Genthe and American women geographers? In her 2004 presidential address to the Association of American Geographers Janice Monk provides the answer: “For academic men, including geographers, aspirations for professional standing, research credentials, and disciplinary prestige meant building masculine preserves, the practice and sometimes articulation of values that placed women and men in different places and in places of unequal power.” The male AAG leadership had consciously constructed an exclusionary business model which relegated women geographers to the sidelines.