By Shannon White

The On the Waterfront oral history project is a collection of interviews from residents of Richmond, California conducted by the UC Berkeley Oral History Center in the 1980s. These oral histories span decades, offering an interesting glimpse into the history of the Bay Area in the early- to mid-twentieth century. This collection features interviews from shipyard workers, cannery employees, fishermen, and early residents of Richmond, many of whom have resided in the area for decades and have witnessed firsthand the city’s evolution over the better part of a century.

These interviews devote a great deal of time to talking about the development of the city as a result of World War II. Common themes throughout the On the Waterfront project as a whole include labor practices, race relations and discrimination, and industrial growth and urban development in the Bay Area.

During the 1940s, Richmond experienced a massive influx of workers, many of whom arrived from the southern United States as part of the Great Migration, seeking wartime employment at local businesses or the Kaiser Shipyards. “I thought it was in the neighborhood of eighteen to twenty thousand. By the time Kaiser came in and all the shipyards moved in there, we were over a hundred thousand,” Joseph Perrelli, whose family founded the Filice and Perrelli Canning Company, says of the rapid population and industrial growth in Richmond as a result of wartime industry.

1985-95-34.

In his interview, Perrelli describes the history of the Filice and Perrelli Canning Company, which began in 1913 as a small family business and grew exponentially during the war.

They would ask us to bid on their needs to feed the army as far as tomatoes and fruit was concerned. We were competitive. We had to bid against each other. We bid against our fellow canners. But the percentage that the military allowed us was much greater than we could get in competition with our fellow canners. Naturally we made some money on the sales that we made to the government, to the military.

The increased need for labor during the war meant that job opportunities opened up en masse for women and people of color, many of whose testimonies were put on record by the Oral History Center. Here, Lucille Preston describes her experience working as a welder in Richmond during World War II:

We would have to punch the time clock at eleven-thirty. I would leave home around eleven-fifteen. . . .Then we would have to go and get our own welding lines. I’m sure you don’t know what that is, but it looks just like a water hose, these welding lines. I would have to have two, one on one shoulder and one on the other, and I would have to climb up a ladder or go down in a hold on a ladder and carry those on my shoulders.

Preston looks back on the hands-on work she performed as a positive experience, recalling, “We would have to go out in the water on the ship. The ship was floating while we were on there welding. So it was really fun. I really enjoyed it.”

At the same time though, Selena Foster, the owner of the Oakland-based restaurant Selena’s Kitchen and an employee of Lou’s Defense Diner during World War II, discusses hiring discrimination for black women looking for shipyard work, saying:

There were blacks out there but mostly the white girls were the ones who got all the training. They all had to wear the same welding suits because this was a training outfit. So they would just try them for so many minutes, and then they would try the other. We tried the whole day to get fitted. Other girls kept coming, white girls. Alma was kind of chubby but she wasn’t fat and at that time I only weighed about a hundred and ten, and it seems that we were too big. This was just prejudice.

Marguerite Williams, a long-time Bay Area resident, also recalls an almost instantaneous increase in racialized violence and discrimination in conjunction with the growing black population in the Bay Area:

It seemed like overnight people on the street would be fighting with knives and everything. . . . When we first came to Richmond in 1946, [Harry Williams] and I and the kids, there was still a lot of that bad feeling, because you would go into the store downtown and the people wouldn’t want to wait on you.

Harry Williams, whose mother worked for the Filice and Perrelli Canning Company in the 1930s, discusses the lack of cannery employment for people of color in the decades following: “I don’t think they hired any blacks that I know of. If they did, they had menial work. They weren’t working on the line.”

Wartime industry in Richmond brought both economic success and population growth to the city, but at the same time brought with it a myriad of issues with racial discrimination and exploitative labor practices. For example, Joseph Perrelli discusses early anti-union sentiment in the canning industry, which led to protests and strikes among the Filice and Perrelli labor force, something Perrelli recalls as “labor activity that was inamicable to our interests at that time.”

Aside from these wartime industries, many other enterprises saw wild success in Richmond over the years, including several fishing and whaling operations.

Pratt Peterson, a lifetime fisherman and former employee of the Richmond Whaling Station, talks about the Bay Area whaling industry over the decades. Here, Peterson discusses the early days of San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf:

That was a long time ago. You talk about San Francisco being a different town. When I was fishing shark, I lived on a boat at Fisherman’s Wharf. Fisherman’s Wharf wasn’t what it is now. There were a lot of vacant lots.

When discussing the current state of the Richmond Whaling Station, which closed in the early 1970s, Peterson recalls, “The slip is still there where they pulled them up, and some of the winches are still there. A lot of the equipment to cut the whale up is still there. Of course, it’s all rusted out now, but they haven’t moved it out.”

Dominic Ghio, a lifetime commercial fisherman, describes his family’s experience fishing and shrimping in the Bay Area for almost a century. Regarding his and his siblings’ work, Ghio says:

It was in San Francisco Bay and San Pablo Bay. We used to commute. We would park our boats in Richmond. That was in the 1930s. And we slept on the boat five days a week. Then, from Richmond we used to go commute home and get changed, take a bath and do what we had to do. Then on Sunday evening in the afternoon we’ll go back and do it all over again. Three hundred and sixty-five days of the year all around.

The stories in these oral histories span the better part of a century of Richmond’s history and include the interviewees’ perspectives on issues that are still very much relevant to the Bay Area of the twenty-first century.

Stanley Nystrom, a longtime resident of the city, discusses the widespread “drug panic” of the 1980s, noting that though these issues affected Richmond, they were not exclusive to the Bay Area:

Now it’s nationwide and worldwide. It has affected the economy, it has affected the crime, it’s affected people in such drastic ways. So you can’t really relate that to Richmond alone. It’s all over everywhere.

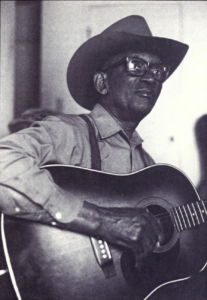

Lewis Van Hook, a member of the Singing Shipbuilders gospel quartet during World War II, gives his thoughts on life in Richmond over the years, mentioning the city’s experience with police brutality at the time of the interview in the early 1980s and the 1983 NAACP lawsuit against the City of Richmond in response to police behavior:

I think it’s still a good place to live, but I would say, in some ways, there’s lots of room for improvement. This problem that they’ve been having now with the police has been kind of disgusting. I think there needs to be some improvements both ways. . . .These lawsuits that they’ve been having—I don’t know, I think of it and think of both sides of it. I know you have some brutality on the police’s side. We’ve had some all right.

The interviews of this oral history project are vibrant and interesting, providing a wealth of information about life in the Bay Area during a time of massive population growth, industrial evolution, and urban development. The narrators for this project have unique perspectives on the changes that Richmond has experienced over the years, and many also share their hopes for the city’s future as well.

You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

Shannon White is currently a third-year student at UC Berkeley studying Ancient Greek and Latin. They are an undergraduate research apprentice in the Nemea Center under Professor Kim Shelton and a member of the editing staff for the Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics. Shannon works as a student editor for the Oral History Center.

Related Resources from the OHC and The Bancroft Library

In addition to the On the Waterfront project, the Oral History Center has several other projects about the history of California. The Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project in particular contains many interviews concerning the Bay Area in the mid-twentieth century. For an overview of some of the oral histories contained in this collection, check out the article, “Bury the Phonograph: Oral Histories Preserve Records of Life in Hawaii During World War II” by Shannon White. For an article about Richmond residents’ memories of Juneteenth, see “Learn about Juneteenth through Oral History” by Jill Schlessinger.

Photographs of Selena Foster and family, accompanying her oral history interview. Bancroft BANC PIC 1993.050–PIC.

Richmond Shipyard photographs. Bancroft BANC PIC 1983.010-.019–PIC.

Henry J. Kaiser pictorial collection: Approximately 150,000 items (photographic prints, negatives, and albums). Bancroft BANC PIC 1983.001-.075–PIC and other locations. See especially Richmond Shipyard workers.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.