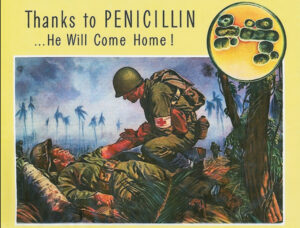

In the history of war, soldiers died more often from infectious disease than from the initial blasts of artillery. Danger from bacterial infection affected people from all walks of life. A person with a minor cut might die within days, bacterial pneumonia was a leading cause of death, and while the advent of sulfa drugs in the nineteen thirties saved countless lives and transformed medicine, there was little physicians could do to save some patients. Until World War II, that is, thanks to the widespread use of penicillin. Discovered by bacteriologist Alexander Fleming in 1928, the Penicillium mold was not harnessed into a widely available treatment until World War II. At that time, penicillin was made available to soldiers and, to a lesser extent, those on the home front. From then until today, antibiotics remain the go-to treatment of bacterial infections worldwide, and the driving force behind a dramatic increase in life expectancy. An interview with Dr. Morris Collen, who treated workers in the Kaiser Shipyards, provides insights into this watershed moment in medical history. Additional oral histories take us beyond the initial scientific breakthrough to show penicillin’s effect on medicine, the pharmaceutical industry, and beyond.

“And to this day I keep saying it was a miracle. He recovered.” — Dr. Morris Collen, on giving penicillin to a patient for the first time in 1942

Early researchers who had witnessed penicillin’s effects on otherwise incurable patients hailed it as a miracle cure. During World War II, the potential of penicillin as a magic bullet was so powerful — the therapeutic results so speedy and effective — that scientists recognized the treatment could make a difference in the outcome of the war. But turning Penicillium into penicillin was slow, the output minuscule, and the technology to support mass production elusive.

A team of scientists from Oxford University intent on solving these problems — Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, and Norman Heatley — realized that they couldn’t successfully make the medical advances needed within war-torn, resource-strapped England. They sought support for their endeavors in the United States in the summer of 1941, freely sharing their research findings and techniques.

The Oxford team easily persuaded scientists at the USDA, pharmaceutical companies, and elsewhere of the value of penicillin. After formally joining the war in December 1941, the United States government took over the research and production of penicillin, mobilizing government agencies, research laboratories, universities, and pharmaceutical companies in the United States and Great Britain. The ability to produce penicillin in bulk became a top priority for the war effort, behind only the Manhattan Project.

As a result of this unprecedented international and inter-industry cooperation (not repeated until the coronavirus crisis and Operation Warp Speed), the United States was able to produce more than two million doses of penicillin in the lead-up to D-Day. This mass production of penicillin saved the lives of countless troops and likely made a difference in the outcome of the war.

An interview by the UC Berkeley Oral History Center with Dr. Morris Collen provides insights into this watershed moment in medical history. Collen was interviewed by the Oral History Center’s director, Martin Meeker, for the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Oral History Project on evidence-based medicine. In 1942, Collen became the inaugural chief of medical service at the first Kaiser Permanente hospital in Oakland, California, serving those who worked for the Kaiser Richmond Shipyards, and also led Kaiser Pemanente’s research division. In his oral history, Collen describes in depth the difficulty of treating patients with pneumonia, and how penicillin changed everything.

Then we began to see patients with pneumonia. A lot of women came to work. That’s where Rosie the Riveter started. Mr. Kaiser sent railway cars around to pick up men to work in the shipyards. All the healthy men were in the armed services, so the trains went around and picked up whoever wanted to get to work. So a lot of them were alcoholics and not in good health. When they hit the Richmond shipyards, where it’s cool and damp, within a few months we were getting — I remember we had ninety patients with pneumonia at one time.

When we first started there was no treatment for lobar pneumonia, pneumococcal type, except horse serum, and the people almost always got sick with serum sickness. It was a terrible treatment, but was all we had. Then from Germany came sulfanilamide, and then sulfathiazole and sulfadiazine, and a series of sulfa drugs, and we began to treat pneumonias with them. That’s where we began, I would say, our first clinical research, evaluating different treatments for pneumonia.

Finally when penicillin came along, Chester Keefer in Boston became the czar controlling penicillin. Ninety percent went to the armed services, and 10 percent, about, went to the United States. We had so many pneumonias and we had reported already in a journal that we were treating large series of pneumonias. So we got the first dose of penicillin in California, and treated a young man with a very severe lobar pneumonia, type 7. They all died from that, and this poor fellow was going to die. So we gave him this one shot of 15,000 units, and to this day I keep saying it was a miracle. He recovered. Then gradually more penicillin came, and we switched to using penicillin.”

Interviewer Martin Meeker: How long did it take for penicillin to ramp up in production?

Collen: Oh, I don’t remember exactly.

Meeker: When was it no longer a rarity to use in the clinic?

Collen: Well, the war ended in ’45, so it became available thereafter. See, when the shipyards began to close down from 90,000 members to 14,000, then most of these workers left. By then the first clinic building was built, and I had some twenty-five beds or so. We still had a fair number of pneumonias, but it wasn’t like it was in the shipyard days. And then we used penicillin routinely, and we had no trouble in getting it after ’45.

Meeker: So after mobilization for the war ceases and it’s not all going overseas, then you have more access to it for the domestic scene?

Collen: That’s true; it became available for civilian patients.

The Oral History Center archive contains more than 100 oral histories that reference penicillin. Some of these are reflections of those who benefited from penicillin, others of bereaved family members whose loved ones died before it was available. Some references are from scientists, physicians, entrepreneurs. The mentions are usually brief, often in passing, as these individuals were being interviewed for other reasons. Just a few examples are below. The oral histories take us beyond the initial scientific breakthrough to show penicillin’s effect on medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. Together these oral histories highlight how penicillin revolutionized not just the practice of medicine, but also how people experienced it.

Alice Lowe: Commissioner on the San Francisco Asian Art Commission, Asian Art Museum Oral History Project

Oh, I didn’t tell you that my father became ill because he tripped one day, when he was visiting one of the canneries for which he hired people, and he got an infection. I guess that was before penicillin. He became kind of an invalid, and so my mother had to take care of him.

Paul Boeder: PhD, Teacher of Physiological Optics, Ophthalmology Oral History Series

She had a miserable, early death, I hate to tell you. After Clara came Eda. Eda was the prettiest of the Boeder girls. She also had a beautiful voice; we loved to hear her sing. When she was thirteen, she contracted diphtheria in school. Penicillin wasn’t heard of at that time; she died in a day or two.

Thomas David Duane, MD: Wills Eye Hospital and Thomas Jefferson Medical College, Ophthalmology Oral History Series

I was saying that there is no specific single way of learning how to treat patients. It’s necessary that you know what can be done chemically and physiologically to put them in a better situation. The other thing is to make them relax. That is the art of medicine. If you want to be a good doctor, you’ve got to do both. You can’t just go into the room and dictate, pontificate, say a few words, and walk off. However, you wouldn’t hold their hand and talk to them all day when, if you gave them a shot of penicillin, it would cure them.

Dr. Russel V.A. Lee: Earl Warren and Health Insurance, 1943–1949

In 1918, when I had the flu ward In San Francisco Hospital, 65 percent of my admissions died of pneumonia. When I went to the Air Force, we had a flu epidemic of the same kind. I called the doctors together. I said, “If anybody dies of pneumonia in this hospital, some doctor’s going to get court-martialed.” That’s the difference, because we could cure it and prevent it by then. That’s largely due to the advent of penicillin and the other antibiotics.

So, that’s what makes it so important now that everybody has access to good medical care, because access to good medical care has some meaning now. It had no meaning in days gone by. If you want to have your kids live, you want to have a good doctor, because then they won’t get diphtheria, they won’t get meningitis, they won’t get polio, and if they do get them, they’ll be cured. This is a revolution.

Herbert Heyneker: Molecular Geneticist at UCSF and Genentech, Entrepreneur in Biotechnology

I always felt that antibiotics were a field that would be open for Genencor, and I tried to push that early on because once we knew how to ferment, production of antibiotics, in my opinion, was also quite an interesting opportunity and very valuable. The penicillins and cephalosporins in the world were huge multibillion-dollar products, and still are.

C. Judson King: A Career in Chemical Engineering and University Administration, 1963–2013

The history of freeze drying in the food industry is actually kind of interesting. It doesn’t start in the food industry. The big push on freeze drying came from World War Two. It came with the isolation and stabilization of penicillin. This was the first way to isolate penicillin so it could be used as a medicine, and it was [also] used for blood plasma. A lot of freeze-dried blood plasma. The freeze drying stabilizes it. The penicillin would go bad if it weren’t dried, and this was the one way to dry it, and ditto for the blood plasma. That was the start. Then as we came out of World War II, it was recognized that freeze drying could have uses in the food industry.

August 6, 1881, is the birthday of Alexander Fleming.

How to search our collection by keyword

To conduct a key word search, from the search feature on the Oral History Center home page, type penicillin or any keyword and click search. On the next page, toggle on “full text.” The results page will list all the oral histories that mention penicillin, showing the interviewee name, title of the oral history, and a snippet of the abstract. Results are easy to skim. You can then click on any oral history to be brought to a page with a description of the oral history, a PDF of the oral history (which you can read and search on the page or download), along with other information, such as publication date, project, related resources, and more.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.