This interview with University of Chicago economist George S. Tolley is the latest in our series of interviews with Chicago economists as part of the Economist Life Stories project. However, along with this twenty-hour interview, we are also releasing online for the first time the oral history with his father, Howard R. Tolley, first head of UC Berkeley’s Giannini Foundation, and chief of the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (USDA) during the New Deal and World War II. This interview, conducted by Dean Albertson in the early 1950s, comes to us from the archives of the Columbia Oral History Project, which graciously granted permission for us to publish these interviews together.

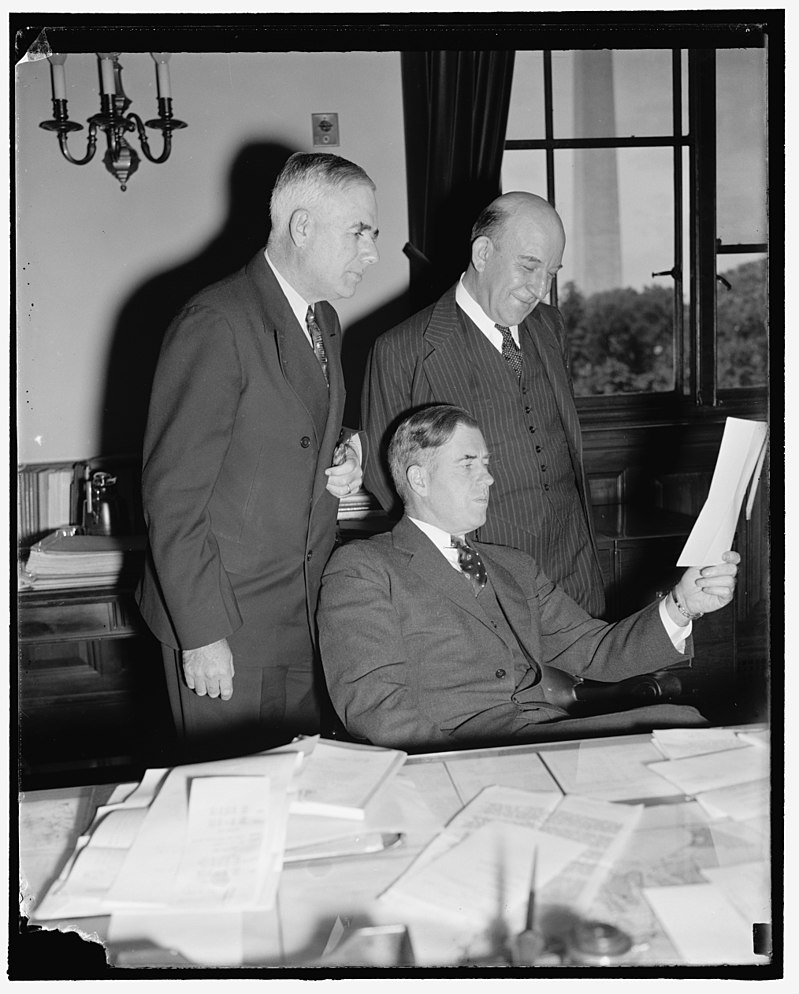

Photo courtesy of https://www.wikiwand.com/en/M._L._Wilson

These interviews will be of enormous importance to historians who are interested in the social and political contexts of the social sciences. Economists at the University of Chicago have been deeply involved in policy advocacy and policymaking since the beginning of World War II. Growing up in Washington during the Great Depression, with a father who was responsible for analyzing and providing solutions to Depression-era farming, George S. Tolley felt that economics was the calling of his generation: to figure out how to prevent such a calamity from ever happening again.

George completed his PhD at the University of Chicago with Theodore Schultz and D. Gale Johnson in the 1950s, and returned as faculty in the 1960s. Schultz was the impresario for the department during this period, bringing his ethic of service to the nation, along with many important contacts. G.S. Tolley was part of Schultz’s agriculture group at Chicago, in which many prominent economists researched problems of agricultural modernization, whether in the rural US or around the world. True to this spirit of service, Tolley became the Director of the Economic Development Division of the Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture in 1964-65, and in 1974–75, he served as Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Office of Tax Analysis of the US Department of the Treasury.

As an outgrowth of his research on resource use and farm labor migration, G.S. Tolley was in on the ground floor of two new research areas, urban economics and environmental economics, neither of which could be more topical today. He also consulted widely for federal, state, and municipal agencies on urban and environmental problems from the 1960s until the present day, both as an academic and in his capacity as CEO of his firm RCF Consulting, Inc. As agricultural economics became central to policymaking in developing countries, so too did urban economics, as megacities mushroomed across the globe, echoing the influence of the agriculture group in this domain. In the late 1980s and 90s, George also produced a seminal work on health economics, which moved the field to a broader view of the economics of wellness.

Social sciences emerged to identify, define, and address the social problems and challenges of the age of which they were a part. If we think of the ideal of science as a belief in the possibility of making knowledge that stands independently of the biases, instrumentation, and idiosyncrasies of observation and experiment, we can understand what the social scientist is up against. Notwithstanding the commitments of many social scientists to such an ideal, it’s impossible for them to escape the social context in which they operate. Both of these oral histories chronicle policy controversies and challenges, and the emergence and evolution of sub-disciplines to tackle particular social problems (low farm income, labor migration, housing inequality and urban sprawl, management of natural resources, or the management of an insurance-based health care system). And both economists focused on the economics of human geography, the price of proximity to markets, opportunities, amenities, and resources. But the larger pattern in both life histories is this: the higher the political stakes of an area of research, the greater the social scientist’s commitment to an ideal of value-free science, often out of sheer necessity. George S. Tolley’s basic approach in his career was humility before the complexity of economic and social phenomena. But that approach becomes a policy orientation in itself: careful analysis of blanket prescriptions or proscriptions, and an understanding of the unintended consequences of well-intentioned plans, an orientation he passed on to his many accomplished graduate students.