By Ella Griffith, UC Berkeley Class of 2020

In the Spring of 2019, I began work in the Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP) under Dr. Roger Eardley-Pryor at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library. Initially, I was interested in narratives around environmental justice and how this theme was, or was not, explored in the Oral History Center’s large archive of interviews with Sierra Club members, several of which were recorded over a half-century ago. The Sierra Club, one of the largest and oldest environmental advocacy organizations in the United States, has historically struggled with issues of environmental justice and inclusivity, and it recently publicized its reckoning with those legacies. My own reading through interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project made it clear that often, the female members within the Club have been the drivers of change on these issues. At the end of my first semester of work, the nuanced roles and perspectives of women in the Sierra Club emerged as the captivating focus in my URAP research.

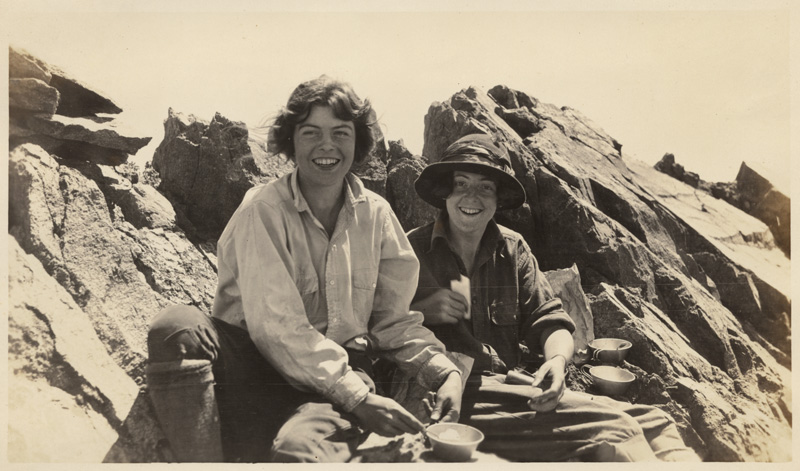

Over the past year, as I continued to read through these interviews of women in the Sierra Club, I pulled out selected quotations and analyzed their content. The capstone of my work is “Sierra Club Women: An Annotated Bibliography of Women’s Oral Histories in the Sierra Club Oral History Project.” This annotated bibliography of Sierra Club interviews with women includes archival photographs and a 2D map that I created by tracing the backcountry hiking routes that several Sierra Club women took on some of the Club’s early High Trips. The thirty interviews I annotated reflect and unpack a variety of common themes that these women grappled with related to their work within, and adjacent to, the Sierra Club and the greater environmental movement. The core themes I identified in these women’s interviews include “Outdoor empowerment”; “Pioneering activism”; “Intersectionality”; “Women as nurturers and cult of domesticity”; “Leadership labor and gender”; “Proximity to male club members”; “Legislative process”; “Early Sierra Club High Trips”; and “Environmental elitism.”

As a woman and environmentalist, reading stories about triumphs and obstacles for these female environmentalists of the past was both exciting and emotional. I gained a better perspective on how far the intersectional environmental movement has come and what aspects of environmental inclusivity I took for granted, thanks to the work of generations before me. At the same time, I felt these themes reflected much of my own life in the present.

By far, however, the most relevant and consistent theme that I saw reflected in my own life is “Environmental Elitism.” Oftentimes, the women interviewed came from very similar affluent backgrounds. They were encouraged to explore the outdoors as kids, and they had the time and resources to do so. Those that did hold leadership positions were volunteers; they did not have to worry about missing supplemental income to support themselves or their families. And every single one of the women interviewed in the Sierra Club Oral History Project were white.

When I started this research, I knew there were narratives and analysis missing from the mainstream history of environmentalism. The annotated bibliography of women in the Sierra Club that I created highlights some of those missing voices. I am glad this resource now exists, and I hope people use it in the future. But there are still many voices missing from our regular education and from our understanding of history. Black and brown scholars, activists, and environmentalists have long been excluded from the narrative of environmental history and denied credit for their contributions. I challenge readers to focus on narratives they have not yet explored within the Oral History Center’s archival collection. Have you had the chance to read through the African American Faculty and Senior Staff project? If so, revisit the important OHC director’s column from February 2020 outlining other important Black oral histories in their collection. In particular, Carl Anthony and Henry Clark and Ahmadia Thomas are among the few oral histories that explicitly focus on toxins and environmental justice. Additionally, have most of the oral histories you have read been narrated by men? My annotated bibliography on Sierra Club Women is just one slim piece of a broader collection of female interviews. For instance, Oral Histories of Berkeley Women highlights some of the oldest oral histories in the collection conducted with women who have been a part of UC Berkeley’s institution since they were granted admittance 150 years ago.

Through my URAP experience, I have learned that oral histories provide us a unique and raw insight into the perspective of the past. Our task, as historians, is to illuminate and analyze all of these voices, especially those that have been left out for so long. But do not forget about uplifting the voices of the present. Who are we not listening to this very moment? Who is making history as we speak? And what will you do to ensure they are not left out in the future?

** A vast collection of papers, books, videos, and toolkits exists on the subjects of environmental racism and justice. Here are some of the resources that helped me learn about environmental justice: Dr. Carolyn Finney, now a professor of Geography at the University of Kentucky, and a former professor at UC Berkeley who was denied tenure, wrote the book Black Spaces, White Faces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors, which examines why Black people are so underrepresented in nature, outdoor recreation, and environmentalism. Another one of my Cal courses introduced me to the report “Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty, 1987-2007,” about grassroots struggles to dismantle environmental racism in the United States. This report from 2007 revisits the foundational “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” study produced by the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice in 1987, and it further examines how hazardous waste facilities exist disproportionately in close proximity to BIPOC communities, while also highlighting the lack of progress in addressing this issue since the first report, now over three decades old. Finally, the EPA created EJSCREEN: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, which combines environmental and demographic data to visualize the intersection of environmental and public health.

—Ella Griffith, UC Berkeley Class of 2020

Ella Griffith graduated in May 2020 from UC Berkeley with a Bachelor of Science in Conservation and Resource Studies. From the Spring 2019 semester through Spring 2020, Ella conducted research in the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned.