Today we release a very special oral history interview: Edward Howden, a pioneering advocate for civil rights and social justice in community-based organizations and early governmental civil rights institutions. Howden, who attended UC Berkeley from 1936 to 1940, was 98 years when we completed his interview earlier this year. To introduce this oral history, we’ve reprinted the interview’s “Foreword” by San Francisco State University Professor Emeritus of History Bob Cherny:

“Today San Francisco and, perhaps with some exceptions, California have reputations for diversity and for inclusion without regard to ethnicity, religion, or gender. California was the first state to elect women to both of its U.S. Senate seats. Currently, the speaker of the state Assembly and the president pro tempore of the Senate are both Latinos. The Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court is a Filipina American. The last six mayors of San Francisco have included a woman, an African American (in a city where African Americans make up less than eight percent of the population), and a Chinese American. Many similar examples could be cited.

One might be tempted to conclude that this level of political inclusion has arisen naturally from a diverse population, but there are other parts of the country where diversity has not automatically brought inclusion. A study by sociologists in 1970 suggested that San Francisco had a “culture of civility” based on tolerance for what they called, in the sociological jargon of that time, “deviants.” However, their explanation for this tolerance is unconvincing, focusing on an alleged “Latin heritage,” a “libertarian and politically sophisticated” working class, and a high proportion of unmarried adults.

Such an analysis leaves out a great deal, both in understanding the development of widespread tolerance of difference, and such tolerance does not automatically lead to inclusion into the social, economic, or political mainstream. There is a difference between tolerating difference and celebrating diversity, and neither itself produces inclusion. Inclusion of diverse groups and individuals into the mainstream has resulted from long-term struggles against both outright racism and more subtle forms of discrimination. In recent decades, historical scholarship has often focused on the ways that various groups have organized themselves to seek equality and inclusion.

The history of efforts to create a more inclusive society involves more than the efforts of excluded groups to organize themselves and demand inclusion. Equally important have been the historical battles that reformers—not themselves members of a discriminated against group— have waged against outright racism and more subtle forms of discrimination and in favor of inclusion. This oral history provides essential documentation to this aspect of the history of California. Throughout his professional lifetime, Ed Howden promoted such goals by campaigning for what he prefers to call human rights: first, in advocating that San Franciscans become more inclusive, then in using the authority of the State of California to bring greater inclusion in employment, and finally as a mediator, seeking to resolve community problems over rights.

I first met Ed at Alma Via, an assisted-living facility where my mother was a resident. Ed often sat at her table during breakfast, and we got to know each other over that breakfast table. I had known a bit about Ed’s work through my research and writing about California history and politics in the mid- to late 20th century. Meeting him in person over breakfast jogged my memory about some parts of his history and reading this oral history has told me a great deal more.

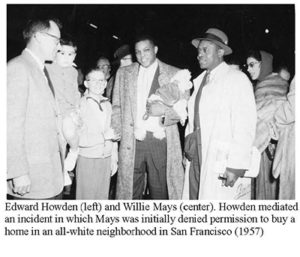

As you will discover from this account, Ed was involved throughout his long career in the struggle for what he defines as human rights. In the pages that follow, he relates how some of his experiences as a student at the University of California, Berkeley, in the 1930s and in the army during World War II led him in 1946 to accept the position of director of the Council for Civic Unity (CCU). Prominent members of San Francisco’s Catholic, Jewish, Protestant, and African American communities had established the CCU, and, as director, Ed worked to develop an awareness of discrimination and to advocate solutions. He utilized public meetings at the Commonwealth Club, radio and later television programs, the city’s four daily newspapers, presentations to the Board of Supervisors, and individual contact with the city’s movers and shakers. He was centrally involved behind the scenes in 1957 in the resolution of the imbroglio over the attempt by Willie Mays, a star player on the recently arrived San Francisco Giants, to buy a house in an all-white neighborhood. Ed also took the lead in writing and publishing A Civil Rights Inventory of San Francisco (1958) that detailed discriminatory employment and housing practices.

In 1959, Ed moved from what would today be called an advocacy organization, the CCU, to a governmental position. The year before, in 1958, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, who had been the California Attorney General and before that the San Francisco District Attorney, was elected governor. As governor, Brown worked with the Democratic leadership in the legislature to create the state Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). Brown appointed Ed as the first director of that agency, and Ed remained in that position for more than seven years, until Ronald Reagan became governor. After leaving the FEPC, in early 1967, he joined the Community Relations Service, a federal agency established within the Department of Justice under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He began western regional director and then became a Senior Conciliation Specialist. He retired in 1986. In that agency, he sought to mediate community problems involving human rights. Much of his work in that agency is covered in a separate oral history, done in 1999, but in this oral history Ed reflects on his central involvement in bringing a peaceful resolution to the 1973 stand-off at Wounded Knee between the FBI and American Indian Movement activists.

Ed’s story is that of one who has worked tirelessly, sometimes prominently but often behind the scenes, to eliminate practices that discriminated on the basis of race and thereby to promote inclusion. At the center of his work stands his belief that respect for human rights is the basis for decent relations among all the groups that make up a diverse society.”