By Kate Tasker and Julie Goldsmith, Bancroft Digital Collections

Last week in the Bancroft’s Digital Collections Unit, we put our new Tableau write blocker to work. Before processing a born-digital collection, a digital archivist must first be able to access and transfer data from the original storage media, often received as hard drives, optical disks and floppy disks. Floppy disks have a mechanism to physically prevent changes to the data during the transfer process, but data on hard drives and USB drives can be easily and irreversibly altered just by connecting the drive to a computer. We must access these drives in write-blocked (or read-only) mode to avoid altering the original metadata (e.g. creation dates, timestamps, and filenames). The original metadata is critical for maintaining the authenticity, security, contextual information, and research value of digital collections.

A write blocker is essentially a one-way street for data; it provides assurance that no changes were made, regardless of user error or software modification. For digital archives, using a write blocker ensures an untampered audit trail of changes that have occurred along the way, which is essential for answering questions about provenance, original order and chain of custody. As stewards of digital collections, we also have a responsibility to identify and restrict any personally identifying information (PII) about an individual (Social Security numbers, medical or financial information, etc.), which may be found on computer media. The protected chain of custody is seen as a safeguard for collections which hold these types of sensitive materials.

Other types of data which are protected by write-blocked transfers include configuration and log files which update automatically when a drive connects to a system. On a Windows formatted drive, the registry files can provide information associated with the user, like the last time they logged in and various other account details. Another example would be if you loaned someone a flash drive and they plugged it into their Mac; by doing so they can unintentionally update or install system file information onto the flash drive like a hidden .Spotlight-V100 file. (Spotlight is the desktop search utility on the Mac OS X, and the contents of this folder serve as an index of all files that were on the drive the last time it was used with a Mac.)

Write blockers also support fixity checks for digital preservation. We use software programs to calculate unique identifiers for every original file in a collection (referred to as cryptographic hash algorithms, or checksums, by digital preservationists). Once files have been copied, the same calculations are run on the files to generate another set of checksums. If they match that means that the digital objects are the same, bit for bit, as the originals, without any modification or data degradation.

Once we load the digital collection files in FTK Imager, a free lightweight version of the Forensic Tool Kit (FTK), a program that the FBI uses in criminal data investigations we can view the folders and files in the original file directory structure. We can also easily export a file directory listing, which is an inventory of all the files in the collection with their associated metadata. The file directory listing provides us with specific information about each file (filename, filepath, file size, date created, date accessed, date modified, and checksum) as well as a summary of the entire collection (total number of files, total file size, date range, and contents). It also helps us to make processing decisions, such as whether to capture the entire hard drive as a disk image, or whether to transfer selected folders and files as a logical copy.

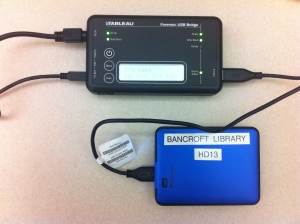

Write blockers are also known in the digital forensics and digital preservation fields as Forensic Bridges. Our newest piece of equipment is already helping us bridge the gap between preserving original unprocessed computer media and creating open digital collections which are available to all.

For Further Reading:

AIMS Working Group. “AIMS Born-Digital Collections: An InterInstitutional Model for Stewardship.” 2012. http://www.digitalcurationservices.org/files/2013/02/AIMS_final_text.pdf

Gengenbach, Martin J. “‘The Way We Do it Here’: Mapping Digital Forensics Workflows in Collecting Institutions.” A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. August, 2012. http://digitalcurationexchange.org/system/files/gengenbach-forensic-workflows-2012.pdf

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G., Richard Ovenden, and Gabriela Redwine. “Digital Forensics and Born-Digital Content in Cultural Heritage Collections.” Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources, 2010. http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub149

BitCurator Project. http://bitcurator.net

Forensics Wiki. http://www.forensicswiki.org/