In April 2024, Oral History Center (OHC) interviewers Amanda Tewes, Shanna Farrell, and Roger Eardley-Pryor traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah, where we presented our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at the annual meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH). We also joined a pilgrimage to the central desert of Utah along with other public historians and several members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee, including survivors and descendants of the Topaz prison camp in Utah, one of the ten US government mass incarceration sites where Japanese Americans were unjustly imprisoned during World War II. Our experiences in Utah at NCPH and at Topaz reiterated how history remains a powerful and living force, and how oral history can help promote that power. Difficult questions about “belonging” appear throughout many of the oral histories in OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, and those same questions punctuated much of our time in Utah this past April.

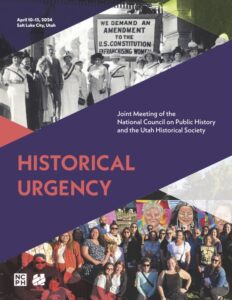

“Historical Urgency” was the conference theme for this year’s meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH) in Salt Lake City, where some 740 attendees presented, networked, and learned together. Presentation topics included community engagement, particularly with communities whose histories face urgent existential threats; communicating the critical importance of history and historical thinking; discourse and dialogue in a time of extreme social polarization; exploration of oral history, especially the collection of oral histories from older generations; and repatriation of human remains and cultural objects. As noted by NCPH president Kristine Navarro-McElhaney, conference discussions highlighted how historians’ work for public audiences remains essential to the fabric of our society, especially during this time of political and cultural polarization—and yet historical perspectives, tools, and history workers themselves have increasingly come under threat. While urgency may seem in opposition to the often slow and deliberate work that oral historians and other public historians do to build trust and lasting relationships with the communities we serve, many of us cannot help but feel a strong sense of urgency and importance in our efforts to collaboratively excavate the past and elevate community stories in ways that help make meaning in the present.

We felt especially honored to share at this NCPH our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. Our roundtable presentation recounted the project’s origins, the trauma-informed interviewing approach we used with these oral histories, and some of emergent themes from the project’s interviews, like “belonging,” “art and expression,” “healing,” and “memorialization.” The roundtable’s discussion was moderated by Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, the Executive Director of the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and a former National Park Service Ranger who recorded her own oral history as part of the project. Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi, both of whom also recorded oral histories as part of the project, attended and also presented at the NCPH conference in Utah, where they heard portions their own oral history interviews during our presentation. Our presentation included audio clips from season 8 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, “From Generation to Generation”: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” as well as graphic narrative artwork by Emily Ehlen, all based on oral histories recorded for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Relatedly, during the NCPH conference, I (Roger Eardley-Pryor) joined other public historians for a tour of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on the University of Utah campus to see a new exhibit titled Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo. The exhibition was curated by Professor ShiPu Wang of UC Merced and features over 100 paintings and works on paper by these three Japanese American women artists, all critically acclaimed with long and productive careers. Yet during World War II, both Hibi and Okubo were unjustly incarcerated in Utah at Topaz, along with Hayakawa’s parents. Pictures of Belonging follows the three artists’ prewar, wartime, and postwar art practices, sharing an expanded view of the American experience by women who used artmaking to take up space, make their presence and existence visible, and assert their own belonging. Many of the exhibit’s artworks are on view to the public for the first time. The exhibit’s titular theme of “belonging” resonated nicely with the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at UC Berkeley, and Okubo even earned her Master in Fine Arts degree in 1938 from UC Berkeley. Our tour of the art exhibit was co-led by Sarah Palmer, Head Exhibition Designer at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, and by Dr. Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. I am especially grateful I could tour Pictures of Belonging with Masako Takashashi, who herself is an outstanding multi-media artist, was born behind barbed wire at the Topaz prison camp in Utah, and who I worked with to record her forthcoming oral history interview for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Our visit to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts also included another new exhibit titled Chiura Obata: Layer by Layer, which presents an in-depth look at the creation and conservation of Obata’s beautiful “Horses” silk screen painting from 1932. Chiura Obata was an esteemed artist and professor at UC Berkeley who was also incarcerated during World War II at Topaz in Utah, where he and Miné Okubo taught art classes for their fellow Japanese American incarcerees. Kimi Kodani Hill, the granddaughter of Chiura Obata, recently presented at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on her grandfather’s life and work, and I’m grateful that during our recent meeting in Berkeley, prior to my own Utah trip, she shared stories with me about Obata’s silk screen exhibit. During the screen’s 2022 conservation treatment, conservators at Nishio Conservation Studio discovered that the four-paneled screen contained hidden full-scale preparatory charcoal drawings of the horses. In addition, they found that the screen’s internal layers were made of practice drawings by Professor Obata and his summer 1932 students. The recently conserved screen, the full-scale under-drawings, and a selection of the practice drawings were all on display at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, along with a short film on the conservation process, which itself is an artform. After we returned to the Bay Area, Kimi Kodani Hill provided a guided tour of another exhibition with forty of Chiura Obata’s watercolors, woodblock prints, and ink paintings from several decades of his life that are currently displayed through mid-July at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

On April 11, 2024, in Salt Lake City at the NCPH conference, Masako Takahashi and Nancy Ukai joined other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee to present their own panel titled “Who Writes Our History?” This panel explored the life and tragic death of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, who was shot and killed while confined in Topaz eighty-one years earlier on April 11, 1943. Their panel also addressed urgent and ongoing challenges over descendant and survivor community consent and collaboration with the Topaz Museum following the recent discovery and excavation of the Wakasa Memorial Stone from the Topaz incarceration site in 2021. That massive, 1,000-pound stone memorial was erected in 1943 by Japanese American incarcerees at Topaz just after James Wakasa’s murder there. But US government authorities quickly demanded the memorial’s destruction in their effort to bury acknowledgement of Wakasa’s death from a bullet fired by a white, nineteen-year-old US soldier who was quickly acquitted of any crime. The Wakasa Memorial Committee’s NCPH presentation, which was standing-room only, featured short films and personal reflections on the life, death, memory, and now-contested stone memorial of James Wakasa.

Two days later, still in Utah, Oral History Center interviewers and several other public historians joined Ukai, Takahashi, and other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee on a pilgrimage to the dust-strewn ruins of the Topaz site on the edge of the Great Basin in Utah’s central desert. The bus ride out to the remote site included watching historical films and sharing personal backgrounds and reflections amongst this group that had assembled from eight different states. Hours later, we arrived at a sparse, sun-bleached landscape encircled by distant snow-capped mountains. Much of the original barbed wire fence around Topaz remains today where some 8,000 Americans were unjustly imprisoned for years during World War II. Crumbled concrete foundations mark sites of now-gone guard towers where US soldiers aimed their guns down at the Japanese American prisoners, and from where they occasionally fired shots, like the one that pierced James Wakasa’s heart in 1943. At the Topaz site, we joined members of the Topaz Museum Board, including board president Patricia Wakida; Scott Bassett, board secretary and education director at the Topaz Museum; and Topaz descendant and board member Dianne Fukami. Together, we all participated in a ceremony organized by the Wakasa Memorial Committee to commemorate Wakasa’s death, as well as the 140 people who died behind barbed wire at Topaz, and the sixteen Japanese American soldiers drafted from Topaz who died during their World War II military service.

The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz began at block 36-7-D, where James Wakasa’s tar-paper barracks once stood. From there, we re-traced Wakasa’s steps across the dusty and now-hauntingly empty landscape to the western perimeter site of his murder, near where the Wakasa Memorial Stone once stood before incarcerated Japanese Americans, under government orders to destroy the memorial, buried it in 1943. An artist’s large recreation of the stone, this one blazing white and made of paper mache and wood, stood near the former burial site of the stone memorial before its removal in 2021. After a land blessing and words of remembrance from survivors born at Topaz, we encircled the artist’s stand-in memorial with name tags bearing the names of our own ancestors. Joshua Shimizu then sang in both Japanese and English the hymn “Rock of Ages,” which was also sung at Wakasa’s funeral in April 1943, and which offered deeper meaning for the missing original Wakasa Memorial Stone.

During the “Rock of Ages” hymn, ceremonial participants attached to the base of the art installation many colorful paper flowers that carried tags naming other Japanese Americans who died in Topaz. The paper flowers we carried to the ceremony were made by Topaz survivors and descendants in honor of the paper floral blossoms folded by imprisoned Japanese Americans at Topaz in lieu of actual flowers for James Wakasa’s 1943 funeral. Miné Okubo, the artist whose work we saw earlier at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, drew several illustrations of Wakasa’s funeral while she was incarcerated at Topaz, including drawings of imprisoned women folding paper flowers to adorn wreaths and crosses. On the desert floor in April 2024, white paper flowers also surrounded the excavation site where the Topaz Museum Board excavated Wakasa’s Memorial Stone in 2021. The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz simultaneously evoked absence and living memory. It was especially meaningful to me (Roger) to join Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi at the ceremony after having worked together to record their oral histories, in which they shared intergenerational memories about James Wakasa and more recent memories about the Wakasa Memorial Stone’s recent rediscovery and removal from that site.

After the ceremony at Topaz, the pilgrimage group boarded the bus and traveled sixteen miles to the handsome Topaz Museum, which opened in 2017 after decades of fundraising and planning in the small town of Delta, Utah. Once there, the pilgrimage group found their way to the back of the museum where we gathered to witness the actual Wakasa Memorial Stone, a one-thousand-pound rock now confined in a small enclosure. After paying our respects to the stone, we toured the Topaz Museum’s exhibits and collections, which include hundreds of artifacts, photographs, and oral histories, as well as 150 pieces of original artwork. The Topaz Museum’s core exhibit explores the complex story of the World War II Japanese American incarceration experience, especially as it transpired at Topaz. The exhibit begins with the racist laws that marginalized early Japanese immigrants, which lead eventually to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibit extends into the traumatic impacts of their exile, with an obvious focus on the Topaz experience, and it concludes with an examination of the Constitutional violations that the incarcerees were forced to endure. I found the Topaz Museum exhibits to be impressive, interactive, and informative. The pilgrimage group then gathered a final time out back by the Wakasa Memorial Stone before boarding the bus and returning to Salt Lake City.

The emotional experiences throughout our time in Utah reminded me of William Faulkner’s line in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” The public history presentations on “historical urgency” at NCPH, the outstanding exhibits on Japanese American artists, the powerful pilgrimage to Topaz and the commemorative ceremony at the site of James Wakasa’s murder, which we shared with survivors and descendants of the prison camp eighty-one years from the date of Wakasa’s death, as well as our trip to the Topaz Museum to see its exhibits and the excavated Wakasa Memorial Stone all reminded us that history is still very much alive and shapes our present experiences. At both the Topaz incarceration site and at the Topaz Museum in Delta, we witnessed some of the still-simmering tensions between Topaz Museum Board members and members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee over what has happened and what will happen to the now-unearthed Wakasa Memorial Stone. Throughout all of those experiences in Utah, I kept thinking on the recurrent theme of “belonging,” including in the oral histories we continue to conduct in the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. “Belonging” carries multiple meanings and invites complex questions. Within what communities, or within which factions of communities, do we find and feel belonging? Throughout history, and up through the present, where have Japanese Americans found belonging? What about the physical artifacts of Japanese American history, like artwork created during World War II-era incarceration, or like the recently re-discovered Wakasa Memorial Stone? To whom do those objects belong? And importantly, who has the right to tell the history of artifacts, artwork, memorials, or lived experiences? To whom does this history belong?

Answers to questions of belonging are elusive because they’re always evolving. I do know, however, how grateful I feel to continue working with individuals and communities to record oral histories that empower narrators to share their own living memories and reflections on the past, and how the personal histories these interviews record will continue to shape our shared present moments. These experiences in Utah helped further inspire our ongoing work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. We hope that you, too, can find inspiration and meaning in these stories, and that they might inform your own sense of belonging.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Oral History Center historian and interviewer

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.