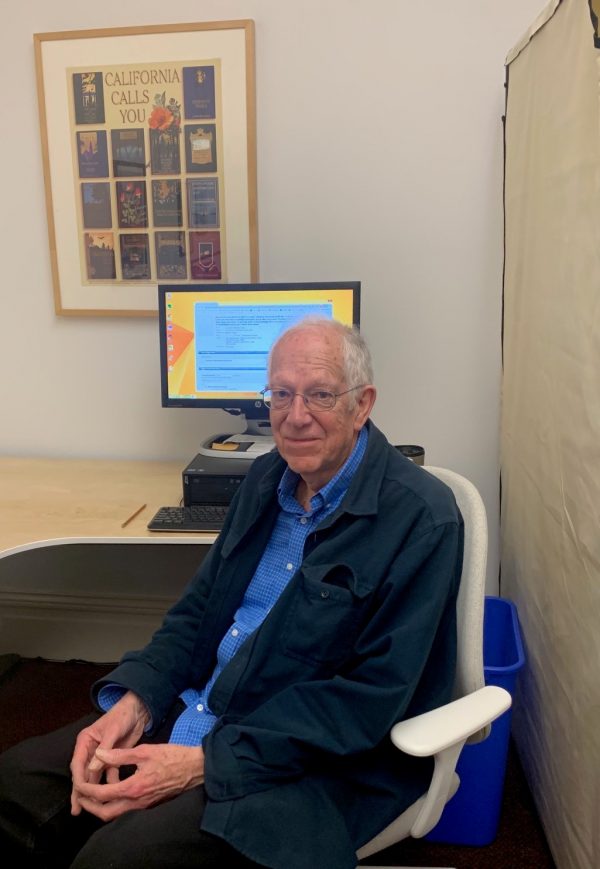

Longtime UC Berkeley Maps and Earth Sciences Librarian Phil Hoehn passed away on February 6, 2023, from complications of colon cancer. He was 81 years old.

Raymond Philip Hoehn, Jr. was born in Cape Girardeau, Missouri on October 23, 1941, the son of Raymond Philip Hoehn and Florentine Jeanne Hoehn. Following World War II, the Hoehn family moved west to southern California and Phil grew up in Pomona. Inheriting a love of maps from his grandfather, he majored in geography at UCLA. In 1967, Phil earned an MLS from UC Berkeley and began his career as the Map Librarian at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library in 1969. He was then asked to assume responsibility for the map collection of the General Library, and managed both collections for several years. When the Map Library was merged with the Earth Sciences map collection, Phil was tapped to lead the new combined unit, eventually known as the Earth Sciences and Map Library, and did so until his retirement in 1996.

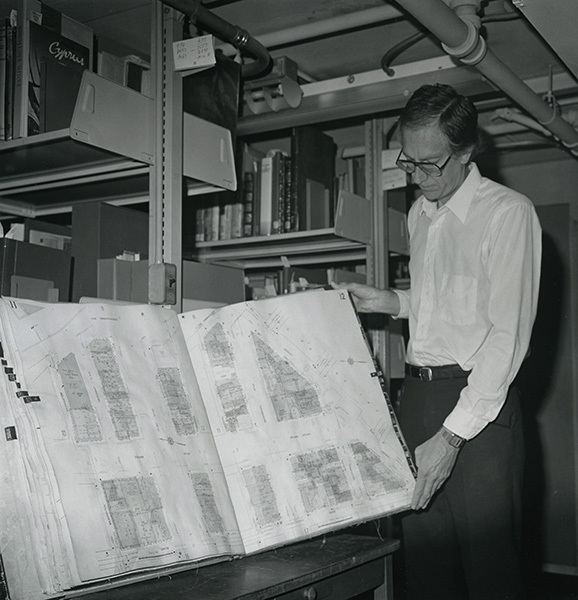

Phil counted among his favorite accomplishments at Berkeley the development and management of the California Maps Project, an ambitious effort funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education to catalog and re-classify some 21,000 maps held in the collections of UC Berkeley and UCLA. Randal Brandt, currently Head of Cataloging at the Bancroft Library, was the project cataloger. “Phil hired me into my first professional position,” he recalled. “He mentored me, encouraged me, and supported me in the early years of my career. He also taught me how to catalog maps, which has been a part of nearly every job I’ve held since then. I can honestly say that I owe my professional career to Phil.”

One of the innovative decisions that Phil made during the project was to include geographic location data in records that describe California Land Case Maps. These diseños, rough manuscript maps, were used as evidence in the court cases which determined the validity of Spanish and Mexican land grants once California was ceded to the United States. Without the online tools of today, determining correct longitude and latitude data for the ranchos represented on the land case maps was not a simple task in the early 1990s.

Although this work was time-consuming, Phil’s decision paid huge dividends several years later when the Bancroft Library undertook the digitization of the maps. When discussing the significance of this metadata, Bancroft Interim Deputy Director Mary Elings, who directed the digitization project, noted the bridge that has been made between the handiwork of 19th century amateur cartographers and contemporary Geographic Information Systems in an important aspect of California history: “Adding the longitude and latitude to the Land Case Map records provided helpful information for researchers in geo-referencing the digitized historic maps, which in turn helps current researchers using GIS systems in their work.”

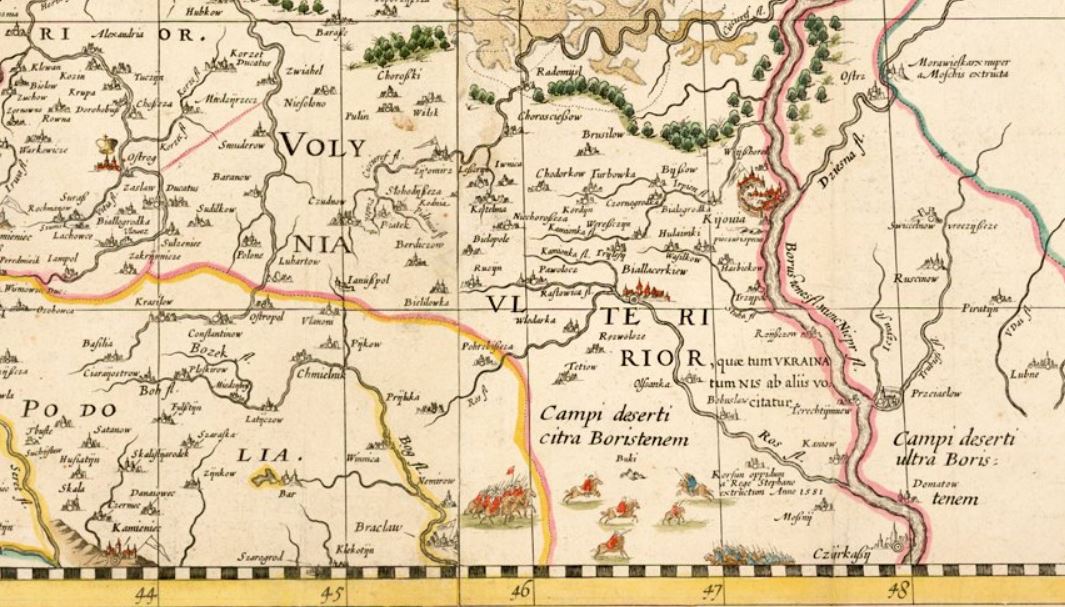

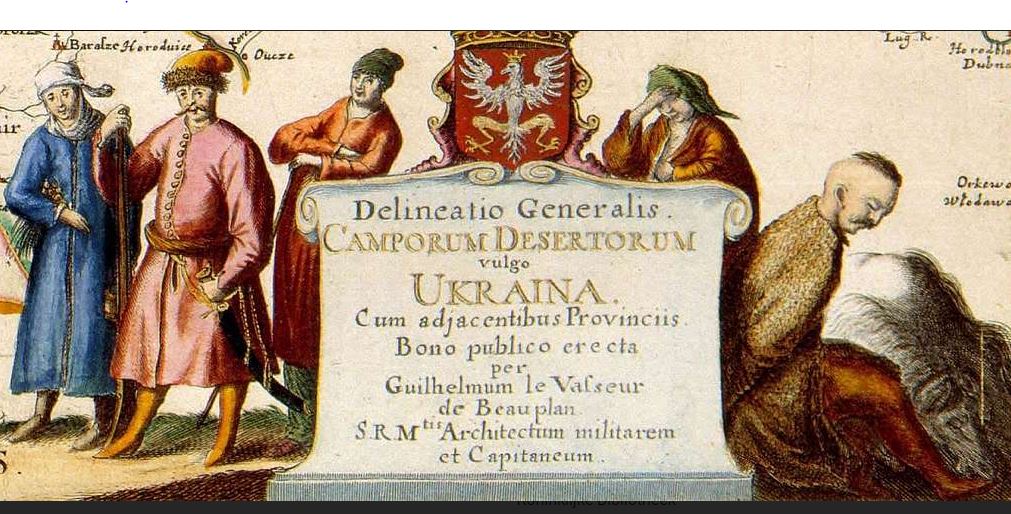

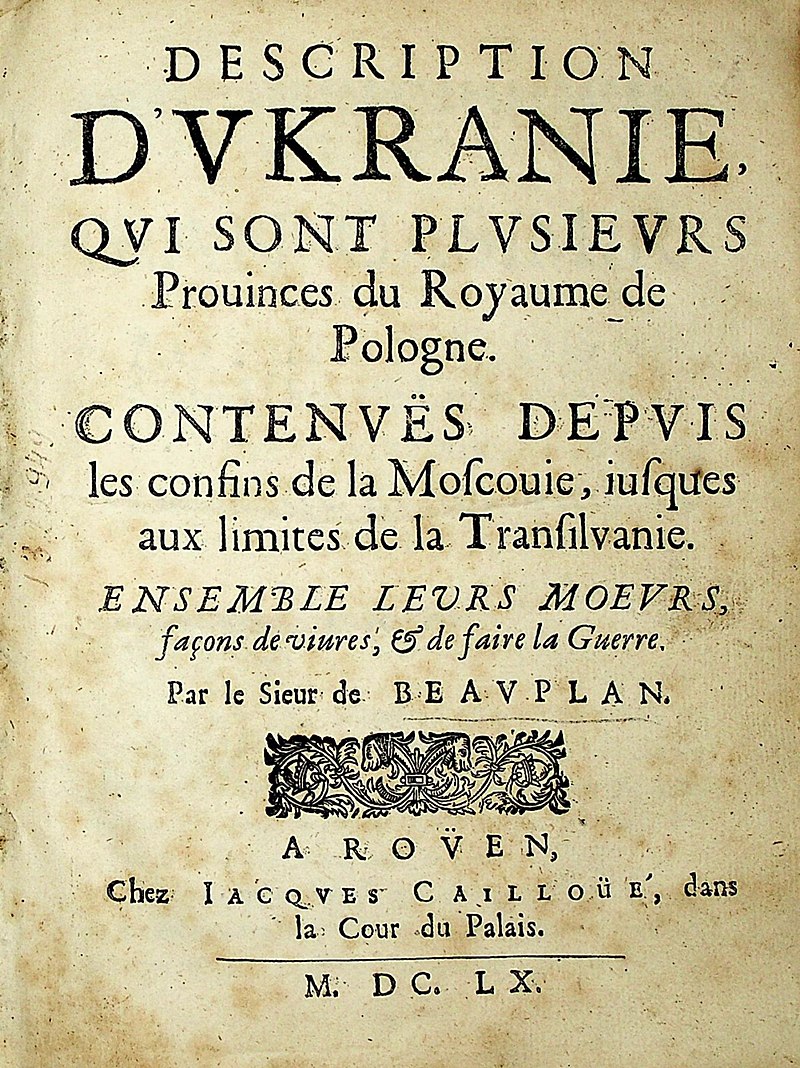

After he retired from Berkeley, Phil headed down the Peninsula and held the position of map bibliographer at Stanford University’s Branner Earth Sciences Library & Map Collections from 1996 to 2000. At Stanford he performed collection development and maintenance, provided reference assistance, and worked to promote university-wide awareness of the map collections and services. Subsequently, from 2000 until 2007 he served as consulting librarian at the David Rumsey Map Collection (now the David Rumsey Map Center at Stanford), where he created thousands of detailed catalog records for digitized maps.

Never one to spend much time “retired,” Phil then launched a second career as a volunteer map cataloger, first at the California Genealogical Society and then at the California Historical Society. In 2020, a CHS blog post described Phil’s work:

In June 2015, Phil Hoehn … took on the daunting task of organizing the California Historical Society’s vast map collection … over 45 drawers of flat sheet maps dating back to at least 1800 (including maps in atlases and books where cartographers depicted California as an island) as well as early mining, railroad, and irrigation maps, bound volumes of Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, and boxes of large rolled maps spanning all the counties in California. During the four years Phil worked reviewing, researching, cataloging, and rehousing the maps he discovered many unique titles, some that appear in only a few other collections in the world. Many of the works, by such prominent surveyors and cartographers as William Eddy, Herman Ehrenberg, Jasper O’Farrell, and August Chevalier, document the birth and growth of the city of San Francisco … [Phil] leaves nearly 4,000 maps now accessible to researchers. From foldout ones in rare books to enormous rolled maps that practically took a village to bring up from the vaults, Phil has discovered, cataloged, preserved, and documented them all.

Frances Kaplan, until recently Director of Library & Collections at the California Historical Society, expanded on Phil’s impact, saying “It is due to his efforts that the entire map collection at CHS is now cataloged and searchable. Along the way he discovered some rare ones and his work inspired the [current] map exhibit.” The exhibit, “Mapping a Changing California: From the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century,” is on view through March 11, 2023.

Phil joined the Western Association of Map Libraries (WAML) in 1969, which was just two years after its first meeting took place. Phil was an active member of WAML his entire career. He found that the benefits of WAML membership included getting good practical advice from friendly, experienced colleagues. Phil also emerged as a wheeler and dealer who obtained many great maps for the UC Berkeley Library by participating in WAML duplicate exchanges. He viewed membership as a form of therapy and described WAML meetings as good places to voice local problems and concerns among like-minded individuals.

Phil had a direct hand in the founding of the California Map Society. Together with Diane M. T. North, who was then a Ph.D candidate at UC Davis, he co-convened a meeting at the Bancroft Library in May 1978, which was the inaugural gathering of the California Map Society. North recalled her long relationship with Phil: “Phil’s knowledge of and deep enthusiasm for maps, all maps, seemed boundless. Anyone privileged to have the opportunity to be guided by him and work alongside him benefited from his professionalism, patience, generosity, and quiet sense of humor.”

Phil had a longstanding interest in fire insurance maps, including local California maps, produced by the Dakin Publishing Company and he published on the subject. His most important publication, compiled together with William S. Peterson-Hunt and Evelyn L. Woodruff, is a reference tool of enduring value to map librarians and researchers, the Union List of Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Held by Institutions in the United States and Canada, originally published in 2 volumes by the Western Association of Map Libraries in 1976-1977. The Earth Sciences and Map Library maintains an updated online version on its website which documents Phil’s hard work.

Together with UCSB map librarian Mary Larsgaard, Phil also co-authored a reference resource which historically has been useful to map librarians, the Dictionary of Abbreviations and Acronyms in Geographic Information Systems, Cartography, and Remote Sensing.

Will Murdoch, a book cataloger at the California Historical Society, who worked with Phil from 2015 until 2019, shared his memories of Phil:

He was my mentor and work colleague in the CHS Library. I cataloged books and Phil processed the maps in that collection. We shared a lot of fun discoveries with each other and learned about the depth of the CHS archives. It was an education for me as Phil’s background was extensive and he was so kind to share his knowledge with me. I miss him and our work together there.

Phil Hoehn played an important role in building the rich and diverse map collections on the Berkeley campus. As a map librarian, map bibliographer, metadata specialist Phil was instrumental in providing expert resource discovery for cartographic resources at many institutions throughout the Bay Area. More important than his professional qualities, however, Phil excelled as a colleague, mentor, and friend. Everyone who knew him and worked with him was made better for the experience.

Randal S. Brandt, Bancroft Library

Heiko Mühr, Earth Sciences & Map Library

Susan Powell, Earth Sciences & Map Library