Living With The Graphic Arts Loan Collection

Share your experience with the GALC!

The Graphic Arts Loan Collection (GALC) at the Morrison Library was created in 1958 by Professor Herwin Schaefer, who believed the best way to foster an appreciation of art was for students to live with actual art. With that in mind, we would love to hear about your experience living with your GALC piece.

Kogyo Tsukioka’s Funabashi: The Floating Bridge

By Eva Allan

We had an unforeseeably long time to live with a print from the GALC; we checked it out more than a year ago, pre-lockdown, and then it became our COVID companion artwork. A Japanese print by Kogyo Tsukioka, Funabashi: The Floating Bridge, it depicts a scene from traditional Noh theater. The plot of the play, as described by the writing on the print, involves lovers separated first by a river and then by death–their disapproving families removed part of the bridge and the man drowned, becoming a lingering spirit searching for rest in the afterlife.

In this scene, the actor playing the woman stands just to the left of the center of the print, by the edge of the doorway or big window. On the other side of the jamb, the actor playing the man-spirit stands behind some railings of a bridge. We can see neither his feet nor the surface on which he stands, which helps us understand the supernatural nature of the “floating bridge.” A pine tree, also with an indeterminate base, appears on the left, also obscuring the supports of the bridge. The pine, long-lived and evergreen, could symbolize remembrance, longevity, and steadfast, undying love (as it does elsewhere in Japanese literature).

One of the pleasures of viewing original artwork is enjoying details you can’t easily appreciate in reproduction. With just a few lines, Tsukioka indicates the sag of organic skin under the painted wooden masks. We see the ribbon that ties the woman’s mask behind the actor’s head. The masks and costumes contribute to the theatrical nature of the characters: the man wears a jacket with enormous grey sleeves and a wide-legged blue pants; his mask is exaggeratedly masculine under an enormous wig; his outfit boasts large-scale patterns with big bamboo leaves and twisting black birds, but with subtle grey and blue colors. The fabric of the woman character’s kimono features a delicate, repeating floral pattern, with heart-shaped leaves like a domestic begonia or violet. Long, abstract narrow ribbons and lapping waves pattern her kimono, wrapping around the actor like fingers, and echo the grasp of her hand that holds in the heavy fabric (in the absence of a belt/obi). This fabric may make her character seem more demure and confined, but her kimono features a prominent red-orange fabric, the strongest color of the print, and she is placed just off center, which contributes to the tension felt between the two tragically separated characters.

We hung this print next to our own impression of the Nihonbashi Bridge in Snow by Hiroshige, which my husband bought when he visited Japan for a conference as a graduate student. The prominent bridge in the Hiroshige emphasized the small bridge depicted by Tsukioka, but the juxtaposition brought out many more differences between the prints. The Nihonbashi Bridge was more about everyday people going about daily errands and the busy world of commerce; because of the snow but also because of their tasks they keep their heads down and hurry towards their purposes. The Funibashi: Floating Bridge scene exists outside of the daily rush, outside even of worldly time, in a fantastic, theatrical setting.

Then, the COVID crisis meant that we all entered a stay-at-home lockdown. During this strange time, the Floating Bridge print took on new layers of meaning: the man and woman seemed to be on opposite sides of a big pane of glass, paralleling our own separation from the world. The Hiroshige print, with its bustle, business, and commercial activity, suddenly became cold and unrelatable, as we stopped running errands or hurrying to school and work. We stayed inside, looking out of the window or at a computer screen; our days merged into a timeless otherworldliness. The characters in the Floating Bridge scene became closer to the daily images on the news: they were like the musicians on balconies in Italy, encouraging healthcare workers; like the teddy bears placed in the windows to delight children on neighborhood walks; or the rainbows drawn by children and taped on windows to symbolize hope in the midst of the COVID-crisis. The separated lovers came to resemble nursing home residents and their visitors, separated by glass windows, unable to embrace.

Too soon, the Floating Bridge print became a reminder of the deaths of so many loved ones, now hundreds of thousands on the other side of the bridge of mortality. So many COVID victims had to say goodbye to their families separated by glass or by screens, wearing masks or otherworldly ventilators and oxygen tubes, barred and blockaded from corporal human touch.

In the end, there is that little pine. Both figures in the Floating Bridge scene turn towards it, rather than making eye contact with each other. It isn’t tall, just a bushy sapling really. Tsukioka allows it to come into the woman’s space, although it seems more likely to be growing outside next to the bridge, as in a Japanese garden. This modest pine becomes the symbol of life beyond human lifespan, of hope that the coronavirus wouldn’t keep us separated from our families forever, and of love that could last beyond mortality.

Thank you for allowing us to keep this print during the lockdown time, for waiving late fees and extending due dates. The extra time offered more moments of spontaneous insight. It encouraged long looking in a year when much of our attention was given to the distraction of computer screens. It was extraordinary to live with an original artwork that seemed to gather new harrowing meaning in this unusual and difficult year, and I’m grateful for the extra time we had with this print.

Stephen Longstreet’s Untitled, Still-Life with Fruit

By Julia Hedelman

So grateful for this program! GALC provides a wonderful opportunity for students who may be limited for financial reasons or otherwise to make their living space feel more homey and comfortable. The pieces I had during my time at Cal were beautiful and I think it’s a lovely way to showcase art that may otherwise be sitting collecting dust in a basement for no one to enjoy. Hope this program can continue for many years to come! Thank you.

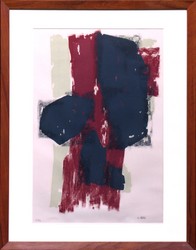

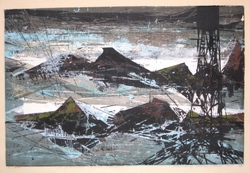

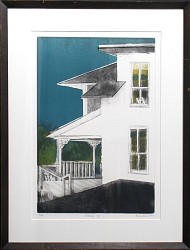

Rodolphe Raoul Ubac’s Composition & Howard Bradford’s Pacific Coast Tower

By Marcel Moran

Had a positive experience. I searched through the online database, selected two pieces, and picked them up at the library. They have been wonderful additions to our home. I will continue to make use of GALC for as long as I am at Berkeley.

Bernard Gantner’s Water’s Edge

By Sarah Harrington

I love the GALC collection. My 3 year old started talking to me about the piece the other day and asking who created it. We wouldn’t have the budget to rotate art in our household without the GALC collection, and the collection is a great way to expose her to different kinds of art!

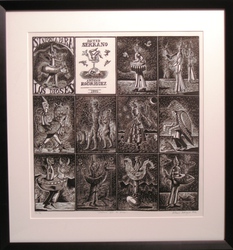

Artemio Rodriguez’s Sinfonia Para Los Dioses & Enrique Sanchez’s El Espiritu Santo

By Keith McAleer

It was so nice to have unique works of art hang in my home! I look forward to trying new pieces. Thanks so much for this awesome program!

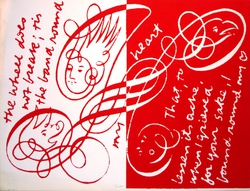

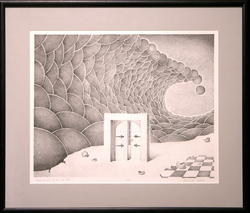

Corita’s h is for my heart & Otto Eglau’s Abstract Floating Landscape

By Sarah Vernallis

My mother grew up in the San Fernando valley and remembers being taken to see exhibitions of work by Sister Corita Kent and her students. I remember being taken by my parents to see a documentary about her political art and radical teaching. It was a pleasure, then, to have one of Kent’s prints up in my home for a year, trying to decipher its poetic lines and staring at her penciled signature.

Hannah Ferenback’s Closing Up & Mark Daniells’ Garden Island III

By Anonymous

The GALC prints that I checked out this year helped provide a burst of color on the walls. They were always a talking point whenever we had company and really made our apartment look classy and put-together. I hung Garden Island III on the wall across from the front door, and it provided a beautiful focal point as soon as we entered the apartment.

Gottfried Honeggar’s Forest Fruit & Herlinde Spahr’s Aeneid 7/12

By Yuen Ho

These gorgeous prints allowed us to bring high quality art into our home. Whether decorating our bedroom or study nook, seeing these prints everyday gave us a jumping point for conversation, reflection, and aesthetic appreciation. Thank you for the opportunity to cultivate a love of art within our humble home.

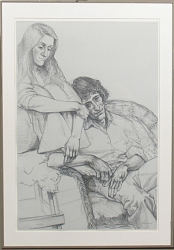

Sigmund Ables’ Weekend Visitors & John W. Winkler’s Dusk at Fisherman’s Wharf

By Evan Larson

The GALC program added so much to my years at Cal. Each year, my rommates and I enjoyed picking out the pieces of art that we would display in our rooms. Throughout the year, I get to enjoy looking up at a beautiful print. Whenever anyone comes over to visit, the usually make a remark about my GALC print – it’s the centerpiece of the room. I especially liked telling other Cal students about the program and seeing GALC pieces appear on their walls next year.

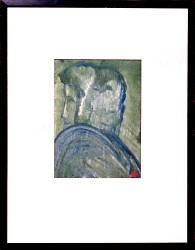

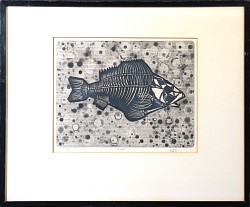

Wilder Bentley’s Entertainer of Our Armed Hosts & Mario Avati’s La Carpe

By Julia Sizek

Our dining room has been a wide open canvas in this giant house where I’ve been lucky to live for a year and a half. The room is one of the darkest in the house, a deep red color that the fast food industry would tell you makes you hungry. We would have never picked such a color, but it preceded us: the dining room, like the rest of the house, is owned by our landlords who are reoccupying the house this summer. When we gave our thirty days’ notice in advance of the impending move, I began taking down the prints in our dining room that we had to return to the library. I had borrowed two, as had one of my housemates. Each of them were beautiful, but the one that I spent the most time examining–mostly when I was pretending to write my dissertation, as I am also doing at this very moment–was “La Carpe” (“The Carp”) by Mario Avati. The print depicts a carp, its skeletal structure visible inside its fishy outline. One of the things that always vaguely upset me about the print is that the fish has no real eye, just a blank socket as one would expect in a skeleton. The blank eye circle is mirrored in the background, a horizontally pinstriped sheet with circular blots that look like carefully drawn circles from far away and water stains from close up. It’s fitting that the skeletal carp is surrounded by water circles, and it reminds me of one of the rules that they told us at the moment when they gave us the picture: don’t put it in the bathroom, they said. We agreed, and instead hung a cheap print of “St. Anthony Tempted by the Devil in the Form of a Woman” (Sausetta), a joke of sorts that we intended to leave to unsettle our bathroom users, a way to lighten the darkness of the house and the fact that it would never be ours.