Out From the Archives: Caroline Service, State Department Duty in China, the McCarthy Era, and After, 1933-1977

“I was tired of being silent.” On December 13, 1951 Caroline Service marched into Senator Hiram Bingham’s office because she “wanted to see the man at the top.” Hours earlier, Bingham’s Loyalty Review Board had determined that her husband, John S. “Jack” Service, would be fired from the State Department on charges of dubious loyalty to the United States. Bingham’s office staff tried to put her off, but Caroline announced that she had nothing else to do and would wait all afternoon for the senator. They let her in. Caroline recalls on page 141 of her oral history, Bingham took her hand and greeted her, “What can I do for you, little lady?” “I could have screamed. ‘Little lady.’ Awful.” She told Bingham that he had done a great injustice to a worthy man. He replied, “Many people have had grave injustices done to them,” and showed her out.

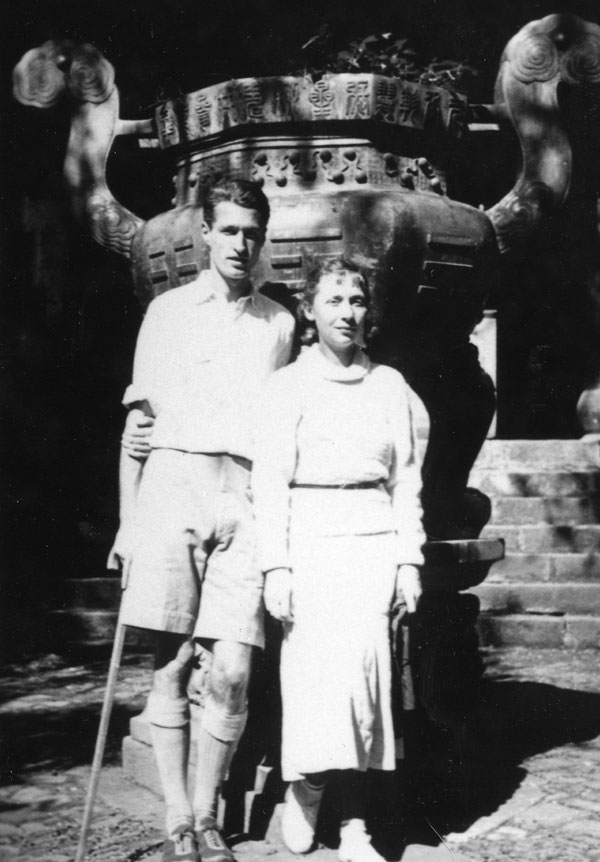

Caroline Service’s oral history, recorded in 1977 by Rosemary Levenson, is volume II to her husband John S. Service’s oral history, but it stands on its own for its unique perspective on foreign service life and the McCarthy witch hunts. Her oral history also details many experiences that were Caroline’s alone. Jack was already in Kunming, China, in 1933 when Caroline, newly graduated from Oberlin, sailed from San Francisco to join and marry him in Haiphong. The journey took her nearly two months, and included having her appendix removed in Shanghai and a terrible typhoon on board a boat moored off Hainan Island. During her time in China, Caroline would be evacuated three times — the first in 1935, the second in 1937, and the last in 1940 — all while Jack remained in China. The Services spent six and a half of their first thirteen years of marriage separated by war and Jack’s work.

In 1951 the country was gripped by anti-Communist hysteria and Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunts found victims in government, academia, and entertainment. Jack Service and his State Department colleagues, the “China hands,” made convenient targets. They were blamed for “losing China,” accused of being Communists, and fired or forced to resign in disgrace. It began for the Services in 1945 when Jack was arrested by the FBI on charges of espionage in the Amerasia case. Caroline, seven months pregnant and staying with her parents in Berkeley, heard the news on the radio. Two months later, in Washington D.C., Caroline would deliver their son Philip on the day Jack was exonerated. The Service family would enjoy a brief period of calm, a post in New Zealand, and the feeling that, “It was over. Nobody would be attacking us or be after us… Jack was no longer connected with China at this time” (page 111). But Jack’s loyalty would be called into question again in 1949 when the Communists won out over the nationalists and diplomatic relations with China broke down.

The Services were determined to appeal the loyalty board verdict, clear Jack’s name, and restore his State Department status. They were vindicated in 1957 when the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Jack’s favor. Later that year, Jack was reinstated at the State Department though he never again was given a sensitive post or a promotion, and he retired early in 1962. After retirement, the Services settled in Oakland and Jack enrolled at UC Berkeley for a master’s in political science. He had a second career at the Center for Chinese Studies, and in 1971 the Services traveled again to China. On page 202 Caroline describes her surprise as their lives circled back around: “If someone had told me earlier that I was going to China in 1971 I would have said, ‘Impossible.’ We never could have believed that such a thing would happen.”

Julie Allen, Oral History Center