I remember sitting in a lecture hall at the University of Hamburg in 1986 during my sophomore year. Friends had told me to come early and I watched as every single seat gradually filled up. There was a lot of chatter.

A middle-aged man stepped onto the podium, Klaus-Detlev Grothusen, a scholar of Eastern European history. Two graduate assistants set up a record player, unrolled a wall map, left a pile of books on his lectern. Grothusen was a man who loved what he was doing. Within the first 20 minutes of his ”Introduction to East European History” he had already fit in extended passages from Gogol’s Dead Souls and played a recording of a Ukrainian children’s song to illustrate his points. The students were laughing.

Then Grothusen switched gears and put on his analytical hat. The essential building blocks of East European history, he argued, were the histories of the multiethnic empires that had long dominated the region. Grothusen pointed them out on the wall map. He pointed to the Ottoman Empire which controlled much of the Balkans. Then he looked at the center of the map, focused attention on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was surrounded by three dynastic empires, Tsarist Russia, the Austrian Habsburg Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia, whose leaders would later construct and dominate the German Empire. The wall map illustrated how those three powers carved up the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in three partitions in the late eighteenth century (1772, 1793, 1795). Grothusen discussed that in some detail.

In Central and Eastern Europe, nation states were latecomers. Many only appeared on the map after the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and the end of World War I (1918-1919). Some of those East European nation states disappeared again, when the Soviet Union revealed its imperial ambitions. In 1986, Grothusen argued that those imperial ambitions were still very much alive.

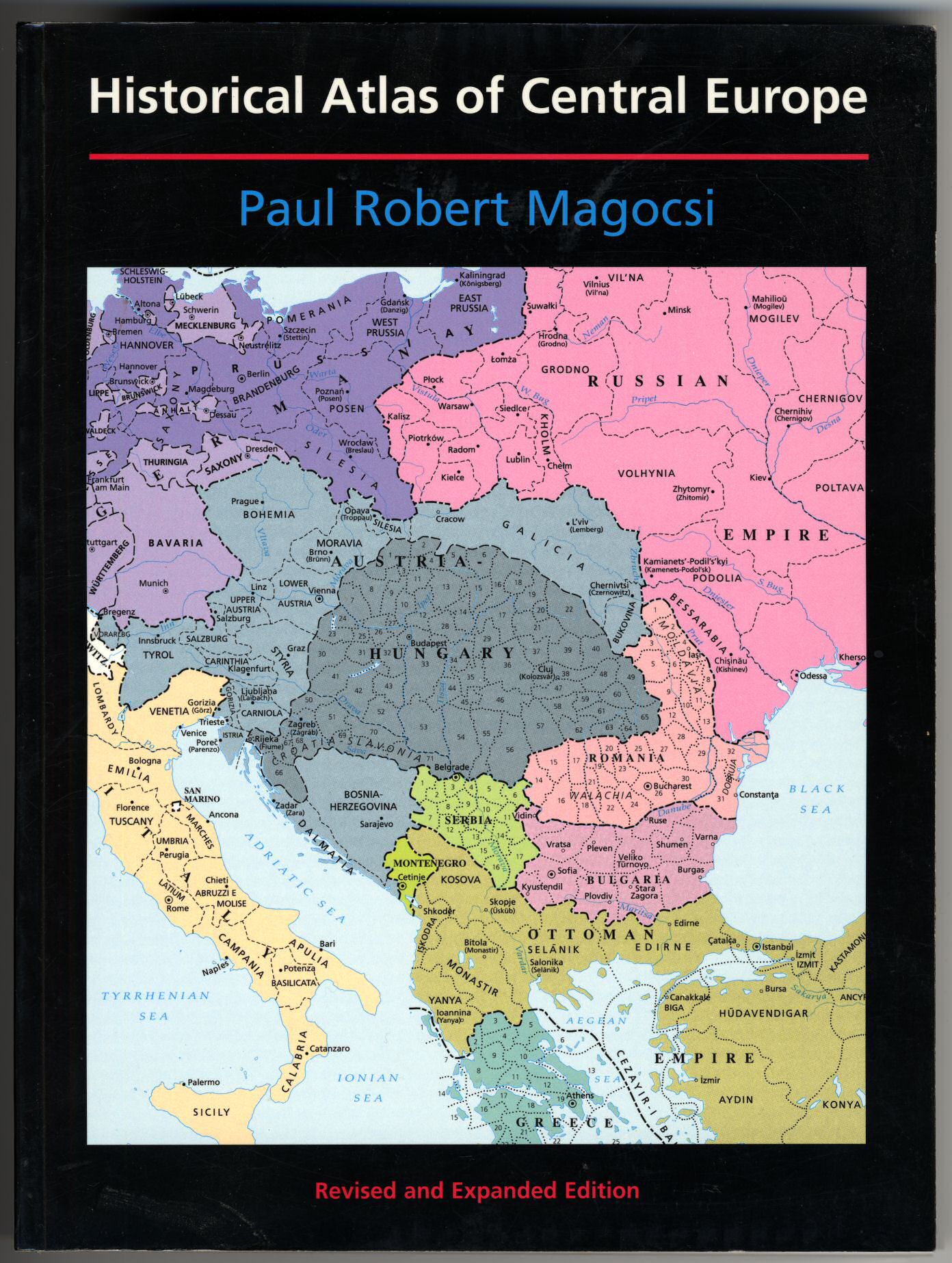

Some historical atlases tell this story well. Paul Robert Magocsi, the John Yaremko Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, authored one of my favorites. The cover illustration of his Historical Atlas of Central Europe , first published in 1993, and now republished in a third edition in 2018 by the University of Toronto Press, gave me pause earlier this week. It shows Central Europe in 1910, on the eve of the Balkan Wars, still dominated by multiethnic empires.

Russian imperial historians, men like Nikolay Karamzin, Sergey Mikhaylovich Solovyov, Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky, and Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin, long ago identified the medieval Kyivan Rus’ as the first authentic state of the Eastern Slavs and laid claim to its legacy. The demise of the Kyivan state, they argued, meant that the center of political gravity shifted far to the northeast, away from Kyiv, to the Central Russian Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal. Initially, the rulers of the town of Moscow were just bit players, overshadowed by their more powerful neighbors, first Suzdal, then Vladimir, then Tver. In the 15th century, however, these historians declared, Moscow finally stepped out of the shadows to fulfill its imperial destiny: After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, court scribes proclaimed that the Tsarist autocracy had a valid title to be the successor of the Roman and Byzantine empires. Moscow thus stepped into her new, self-appointed role as the “Third Rome.”

The tsar himself, the embodiment of sovereign authority, stood at the center of Moscow’s autocracy. By the early 18th century, the tsar claimed to be the “Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias.” And those ”Russias” were carefully enumerated, first and foremost Great Russia (Velikaya Rossiya or Velikorossiya), the territorial core of the Grand Duchy of Moscow; secondly White Russia (Belaya Rossiya), what is still called Belarus today; and finally Little Russia (Malaya Rossiya or Malorossiya), today the independent country of Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin has seized upon this carefully crafted story in his speeches and writings, because it provides a useable national past and seemingly, in his eyes, historical legitimacy for his dangerous and murderous pipedreams of reviving the Russian imperium. According to Putin all Eastern Slavs are essentially Russians, “one people,” a “yedinyi narod.” Fiona Hill eloquently questioned these claims in a recent Politico interview, singling out Putin’s vision of a “Russky Mir” or “Russian World.” Putin and Sergey Lavrov have long argued that Ukraine does not really exist, that its national territory is properly identified as “Novorossiya,” or “New Russia.” Both deny the right to self-determination to Ukrainians.

How do we answer that? Where can we look for an answer? The very idea of what Ukraine represents is wrapped up in another historical narrative, one that was carefully crafted by the leader of the Ukrainian national movement, the historian and statesman Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (1866-1934). As a young scholar, with his published thesis in hand, Hrushevsky was handed a tremendous gift, he was appointed chair of Ukrainian history at Lviv University. This was a newly created position, the very first one of its kind.

Lviv, that great western Ukrainian city, was at that time located in the easternmost reaches of the Habsburg Empire’s province of Galicia. It was the seat of key institutions which spearheaded the Ukrainian cultural revival, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the Shevchenko Scientific Society, and also the Prosvita society, founded in 1868 and dedicated to spreading literacy and education in the Ukrainian language.

Lviv was about the only place where Ukrainian national aspirations could be publicly voiced at this time and Hrushevsky seized that chance. In 1897 he was elected president of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, and rebuilt it to function as a Ukrainian Academy of Sciences-in-exile, with popular and scholarly journals, a publishing house, a library, and a museum.

As a historian and ethnographer, Hrushevsky reconstructed the story of Ukraine’s past, most notably in his magisterial ten-volume History of Ukraine-Rus’, the first major synthesis of Ukrainian history. The first volume appeared in 1898, the final one was published posthumously, in 1937. Hrushevsky summarized his key ideas in an article in 1904, “The Traditional Scheme of ‘Rus’ History and the Problem of a Rational Ordering of the History of the Eastern Slavs.” This seminal essay immediately ignited heated debates because Hrushevsky claimed what should have been obvious all along, that the Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians had distinct identities and histories, which deserved separate historical treatments.

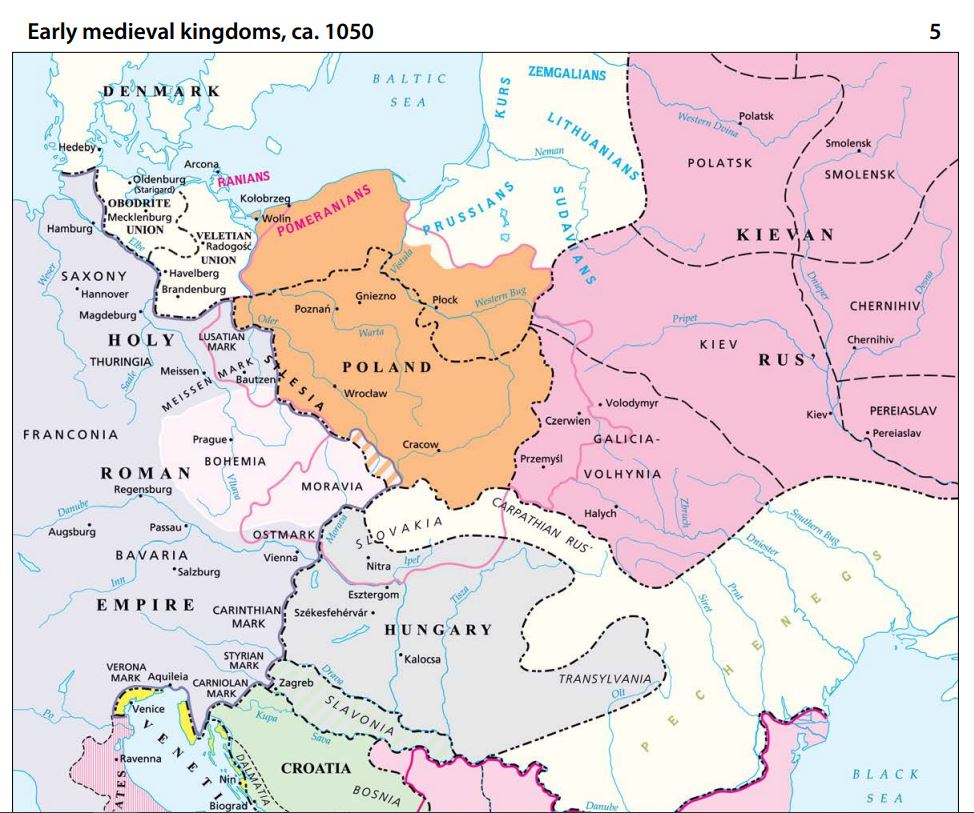

The two principalities of Galicia and Volhynia made up the the westernmost part of the Kyivan Rus’ and were united in 1199 by Grand Prince Roman the Great of Kyiv (Source: Magocsi’s Historical Atlas of Central Europe).

Hrushevsky firmly anchored Ukraine’s history in the West: He showed that the Kyivan Rus’, with its distinct political-administrative structure, socio-economic base, culture and laws, was the creation of southern tribes of the Eastern Slavs. After the disintegration of the Kyivan Rus’, Hrushevsky looked to the southwest and identified a new center of political gravity there. He tied the history of Ukraine to the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (1199-1253) and the Kingdom of Ruthenia (1253-1349) which emerged out of it. The center of the Ruthenian kingdom, ultimately conquered by Lithuanians and Poles, and absorbed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, survived relatively intact as the Ruthenian domain of the Polish Crown, it formed the Ruthenian Voivodeship. Hrushevsky thus tied the history of Ukraine (and likewise the history of Belarus) to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and not to the Tsarist autocracy.

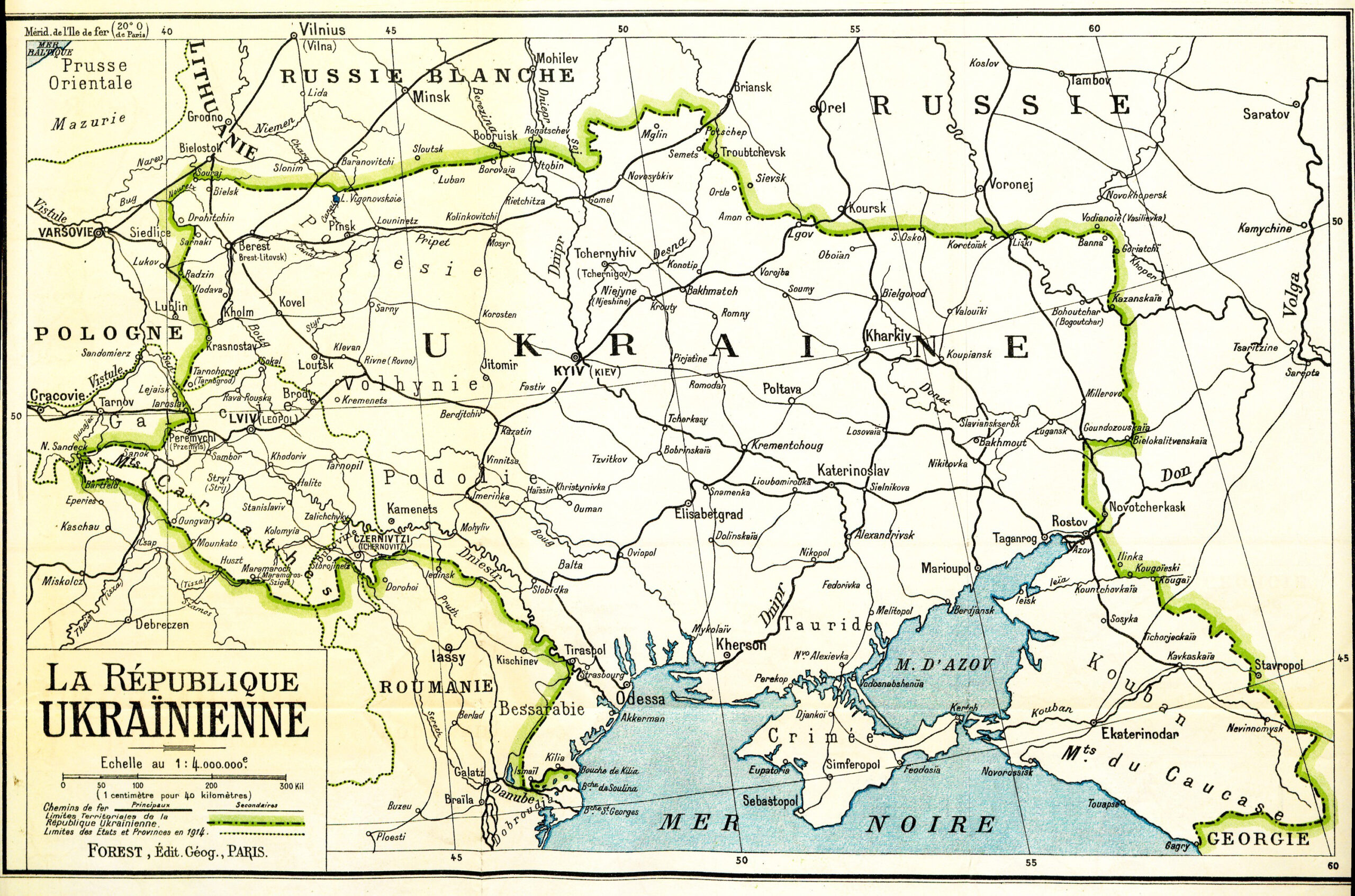

The unraveling of Tsarist power during the February Revolution, the first stage of the Russian Revolution in 1917, opened new possibilities. The Tsentralna Rada (Ukrainian Central Council) in Kyiv, the All-Ukrainian council (soviet) of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, elected Hrushevsky as chairperson. Under his direction, this body soon became the revolutionary parliament of Ukraine. Hrushevsky joined the newly formed Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries, the majority party. In June 1917, the Ukrainian People’s Republic declared its autonomy and was recognized by the Prime Minister of the Russian Provisional government, Alexander Kerensky. In January 1918, after the Bolsheviks took control in Russia, the Rada proclaimed Ukraine an independent and sovereign state. Three weeks later, the New York Times published excerpts from Hrushevsky’s “Ukraine’s Struggle for Self-Government” and introduced him as “one of the new republic’s most eminent men.” As a radical democrat Hrushevsky successfully opposed a Bolshevik takeover and in April 1918 he was elected president, after the Rada adopted a Ukrainian constitution. But Hrushevsky was soon overthrown in a coup d’état by conservative power brokers. The Ukrainian Bolsheviks decamped for Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, and established a rival government there, the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, aided by the bayonets of the Red Army. In the end, the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921) ended disastrously for Ukrainians, their country was divided by Poland and the new Bolshevik regime.

Map of Ukraine, showing the country’ proposed borders. Prepared for the Paris Peace Conference at the end of World War I, 1918.

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, also known as Soviet Ukraine, was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union. In 1923, its All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences elected Hrushevsky as full member and he returned to Kyiv. He held the chair of Modern Ukrainian History and edited the journal Ukraïna from 1924 to 1930, the official publication of the historical section of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. By 1929, with the power of Stalinist operatives on the rise, attacks on Hrushevsky increased, for not adopting official Soviet Marxist interpretations. He was arrested in March 1931, subjected to constant surveillance, and forced to live in Moscow. Like many other Ukrainian intellectuals, most of his students and co-workers were arrested and repressed. Many subsequently died, murdered by the Stalinist regime. Hrushevsky himself died in suspicious circumstances, after what should have been minor surgery, in 1934.

I thought of Klaus-Detlev Grothusen several times these last weeks, how his eyes lit up when he played music composed by Tchaikovsky, or when he read poetry from Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar, one of the seminal works of Ukrainian literature. But I also remember Grothusen’s discussion of the Stalinist system. He quoted Stalin himself, who tried to legitimize his methods by saying darkly that “Russians need a tsar.”

Stalin and Putin share the belief that coercion and autocracy are essential tools in their tool chest. Ukraine, a country that was brutally repressed by Stalin, is now attacked by Putin who seems determined to liquidate its independence. Ukraine is a viable nation state, Europe’s second-largest country, with 44 million Ukrainian citizens. Let’s all help to make sure Ukraine endures and flourishes.