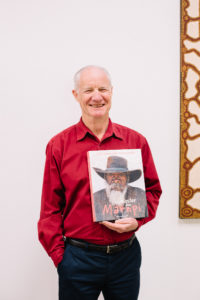

We recently caught up with one of our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute alums, Alec O’Halloran, who recently published a book that was influenced by his work with us. His book, The Master from Marnpi, is based on oral history interviews. O’Halloran reflects on his work, his time with us, and the release on his book.

(Applications are open now for the 2019 Summer Institute from August 5-9. Apply now!)

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

I don’t have a ‘first’ recollection. I’ve always been interested in stories and in the 1990s (in my forties) I was drawn to the larger story of Aboriginal art and history in Australia, which I knew very little about. This led to reading autobiographies and biographies of Indigenous people, as well as attending art exhibitions etc. Oral history interviews were often quoted in stories about Aboriginal artists, particularly older people from remote parts of Australia that most of our population knew very little about.

When I began researching the life of an artist whose work I admired, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, I found out he had done two recorded interviews in his language, Pintupi, a decade before he passed away (1998). I found those interviews – or their translated transcriptions – fascinating! What a life he had led… so different to mine. Those interviews motivated me to look around for more oral history work that engaged with Aboriginal artists in particular.

Q: Tell us a little bit about the project you were working on when you attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute.

I attended the Institute in 2010, in part with support of a travel grant from my institution, The Australian National University in Canberra, where I was undertaking a doctoral program in Interdisciplinary Studies. My thesis project was the life and art of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. I had a rough draft of his life story by that stage, and I was mostly preoccupied with assembling the chronology of events, rather than comprehending his character.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

One thing I still remember from one of the guest lecturers was about ‘listening and hearing’ when working with recorded interviews. And with so many conversations with fellow participants about each other’s projects, I realised I was not fully engaging with the materials I had at hand. So, I when I returned home to Sydney I took a more rigorous approach.

I went back to the original recordings of Namarari (one audio, one video), and the transcripts, and tasked myself to see and hear more than I had before. To not only track events and incidents and the chronology of his life story, but to look beneath and between the lines and sounds for character and personality traits, for nuanced references to culture, to allusions to relationships with other people. I said to myself, ‘These two interviews are like gold, I need to use them to the fullest’. So the Institute motivated me to be much more dedicated to the oral history component of the biographical research about Namarari’s life and art. This certainly improved the quality of my writing when I was integrating Namarari’s voice into a wider story that involved multiple voices and archival sources.

Another outcome too. Oral history as a data-making history-creating method became more important to me. I don’t think I was an expert practitioner, so I tried to improve the quality of my interviewing work. This involved better planning of interviews and better conduct as the interviewer. Also, I saw that I had an opportunity to contribute to the field in a meaningful way.

The region where Namarari lived is called the Western Desert. It occupies a vast swathe of Central Australia. (Bigger than Texas!) My field work took me to that region, first by air to Alice Springs, and then by four-wheel drive (essential for the outback gravel roads). I realised I could do additional oral history work outside my specific research project as part of my travels. During 2011-13 I was awarded two oral history grants by the Northern Territory Government, which I applied to producing two community oral history reports: for the desert communities of Mount Liebig and Kintore. I interviewed some twenty Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and submitted a report, and deposited the interviews with the Northern Territory Archives Service in Darwin. I hope that one day a community member or researcher will come along who wants to write a local history of those places and find those interviews… they can then serve a good purpose. Importantly, but sadly, some of the people I interviewed have passed away.

Q: What’s the status of your project now?

My project, to produce an authorised biography on the life and art career of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, is complete! The master from Marnpi was released on 7 September 2018.

See my website for more information www.alecohalloran.com

Q: How did your biography, The Master from Marnpi, benefit from the use of oral history?

Namarari passed away in 1998, before I started my research, so I never met him and I could not interview him. This contrasts sharply with the majority of Aboriginal artist’s biographies in recent decades in Australia – they are invariably deep collaborations between the author and subject.

My narration of Namarari’s life story is based on his testimony: two interviews recorded in Pintupi, in 1989 and 1992, each conducted in the Western Desert by non-Aboriginal researchers who had travelled there for that purpose (and to interview other Aboriginal people of the area).

Thus it is his (translated and transcribed) voice that runs through the chapters. The many gaps are filled, where possible, with other oral history interviews I did with his relatives, and with art advisers who worked with him across his art career (1971-1998). I also drew on other oral histories, both my original interviews and from the archives, to enrich the narrative, applying more details to local histories of place, and shining a light on prevailing attitudes and circumstances that Namarari and his Aboriginal countrymen found themselves in. Where possible, I added salient photographs from a wide range of archives to illustrate what was referred to in the text by people who were ‘there at the time’.

Q: You have some visual components in the book, like maps. How did you weave visual elements with oral history?

The non-text items are: maps (of Australia, and the Western Desert region where Namarari lived), diagrams (eg, the Aboriginal kinship system), tables (eg, Namarari’s annual art output from 1971 to 1998), photographs of people, places (eg, desert scenes, Namarari’s house), and art (primarily his paintings).

The visual components serve to show the reader something of what the story-teller (eg, Namarari or his relatives) was talking about. If it was an important water-source location from his childhood in the 1930s, I would include a photograph. If it was a settlement where he lived in the 1950s, I would look for appropriate pictures from that era. Unsurprisingly there are many more useful photographs from the 1990s than the 1950s.

I applied a policy of sorts to the inclusion of images: it had to illuminate something in the text, rather than being a decorative piece to fill a space. I sometimes juxtaposed images to make a point, such as two artworks that had a subtle feature in common.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

I have really been preoccupied with my book for several years, so I haven’t been looking for extra inspiration. When I was doing the biographical research I drew inspiration (and understanding) from reading Indigenous autobiographies… they often had the raw truth of historical circumstance from the mouths of those who experienced events and situations and policies.