In PhiloBiblon, Charles Faulhaber transcribes information regarding the former owners of the Biblioteca de Castilla – La Mancha (Toledo) copy (Inc. 3: BETA copid 1479) of Juan de Lucena’s Diálogo de vita beata (BETA texid 1601), printed in Burgos by Juan de Burgos, 8 August 1499 (BETA manid 1932).

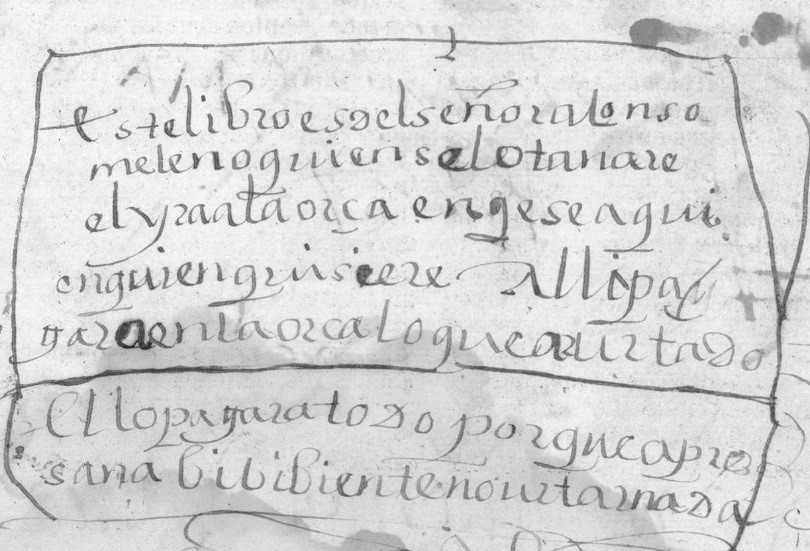

On f. D4r, an ex-libris inscription states that the book belonged to one Alonso Meleno:

As noted in PhiloBiblon, the hand is of the second half of the 16th century. The inscription reads: “Este libro es del señor alonso | meleno quien se lo tanare [sic] | el yra a la orca en qe sea qui|en quien [sic] quisiere Alli pa|gara en la orca lo que a urtado | El lo pagara todo por que a pre|sana [sic] bibiente no urta nada”.

An Alonso Meleno, “escrivano del número,” is mentioned in a document from Toro dated 1552, cited in Luis de Salazar y Castro’s Historia genealógica de la casa de Lara (Madrid: 1597, p. 603). While there is no clear evidence that the scribe Alonso Meleno is the man who owned the book, the dating is consistent with the handwriting.

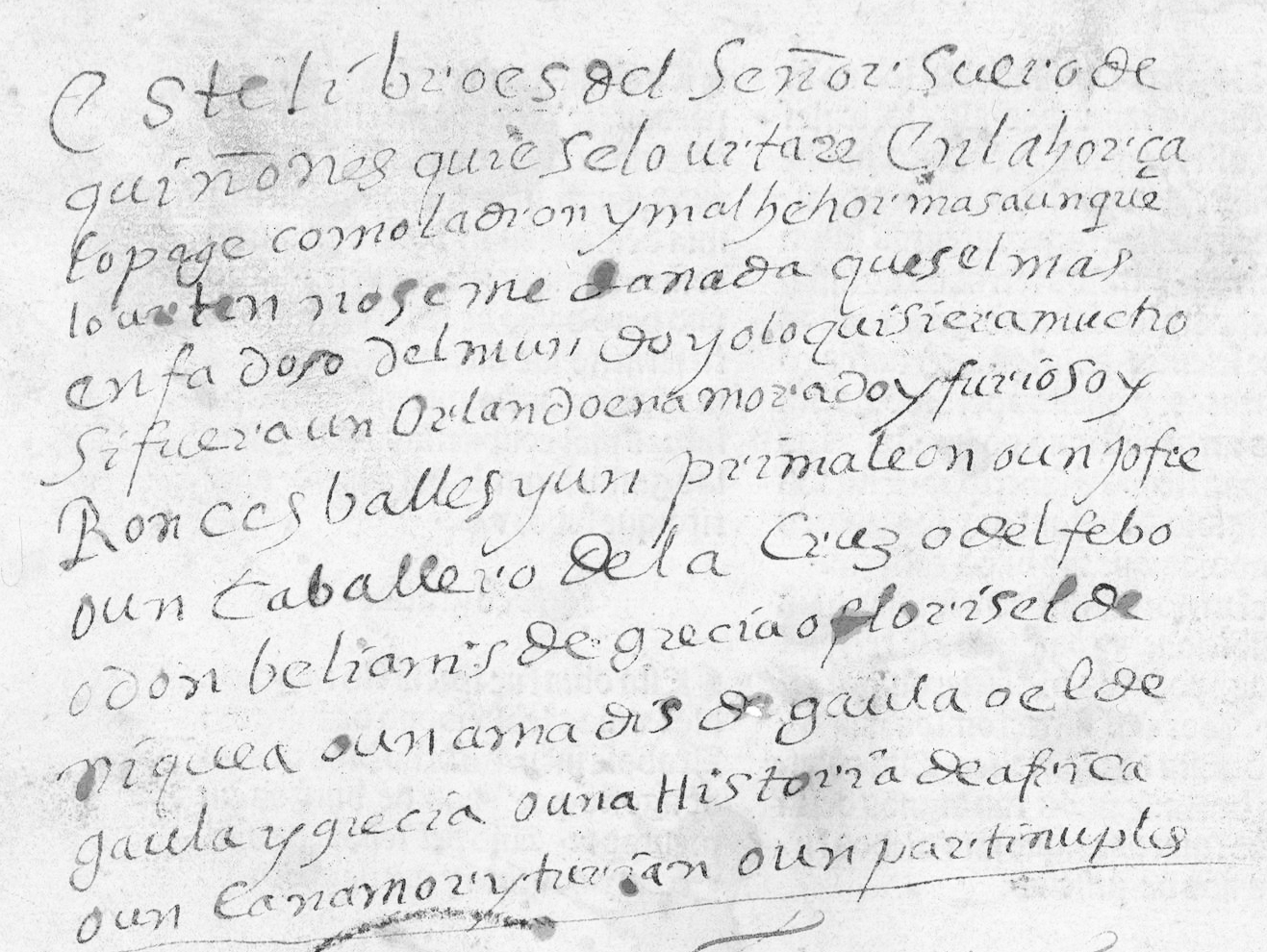

There is a second, considerably more interesting, ex-libris statement on f. D4v:

Toledo: Biblioteca de Castilla-La Mancha, Inc. 3, f. D4v

According to PhiloBiblon, the handwriting would date this ex-libris to the late 16th century. It reads: “Este libro es del Señor Suero de | quiñones quiẽ selo urtare En la horça [sic] | lo page como ladron y malhehor [sic] mas aunque | lo urten no se me da nada ques el mas enfadoso del mundo yo lo quisiera mucho | si fuera un Orlando enamorado y furioso y | Roncesballes y un primaleon o un Jofre | o un Caballero dela Cruz o del febo | o don belianis de grecia o florisel de | niquea o un amadis de gaula o el de | gaula y grecia o una Historia de africa o un Canamor y turian o un partinuples.”

I shall return to this ex-libris below.

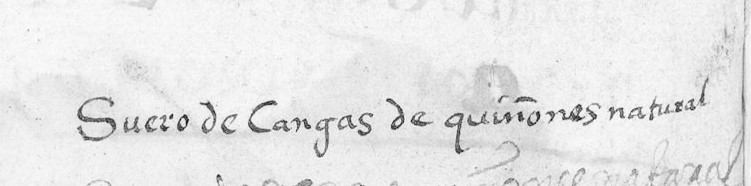

On the same folio side are found the names of Suero de Cangas de Quiñones:

“Suero de Cangas de quiñones natural”

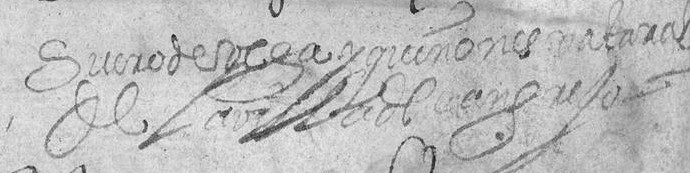

and of Suero de Vega y Quiñones:

“Suero de vega y quiñones natural | de La villa del cangrejo”

Given the differences in hand-writing, it seems probable that three different persons are named on f. D4v:

- Suero de Quiñones, in the ex-libris, after 1555/1556 (see below)

- Suero de Cangas de Quiñones natural, 1st half of the 16th c.

- Suero de Vega y Quiñones, end of the 16th c.

Suero was a common name in the extended Quiñones family even before the time of the famous Suero de Quiñones (ca. 1409-58) of the Paso Honroso (1434), whose daughter Leonor (sometimes referred to as Violante o Teresa) married into the Vega family and whose surviving son, Diego (1436-84), inherited the Señorío de Valdejamuz.

Suero de Cangas (n. 2 above) might be the person mentioned by Alonso López de Haro in the Nobiliario genealógico de los reyes y títulos de España (Madrid: 1622, p. 496): the grandson of a Suero de Quiñones—not the Suero of the Paso Honroso—but possibly the brother of Diego Fernández de Quiñones (1455-92), the first Conde de Luna and Señor de Cangas y Tineo (César Álvarez Álvarez, “Los Quiñones—Condes de Luna durante la Baja Edad Media”, Revista de la Diputación Provincial [Tierras de León] 21 [1981]: 45-60, esp. pp. 49-50).

Suero de Vega y Quiñones (n. 3) might be the son of Juan de Vega y Enríquez de Acuña (d. 1558), Viceroy of Sicily and Señor de la villa de Grajal. Suero de Vega (d. 1585), the great-great-grandson of the Suero of the Paso, held the mayorazgo of the Palencia family line through his grandmother, Blanca Enríquez de Acuña (Rafael Ángel Martínez Gónzalez, “Doña Blanca Enríquez de Acuña, vecina ilustre de Palencia” [Palencia, 2002, pp. 20, 35]). However, I have found no connection to “la villa del cangrejo.”

Finally, Suero de Quiñones (n. 1), author of the ex-libris inscription, may be the great-grandson (d. 1590) and last direct descendant through the male line of Suero de Quiñones of the Paso Honroso (César Álvarez Álvarez, Los Quiñones, señores de Valdejamuz (1435-1590) [(Astorga, 1997, esp. pp. 24, 55-59]); but the identification is debatable.

The Suero de Quiñones of the ex-libris states that his preferred reading is not Lucena’s Diálogo de vita beata but romances and chronicles. According to Daniel Eisenberg and Mari Carmen Marín Pina, in their Bibliografía de libros de caballerías castellanos (Zaragoza, 2000), the first editions of the chivalric romances mentioned in the inscription date from ca. 1496 to 1555.

- Amadís de Gaula (Books 1-4). Ms fragments from the 15th c., with a possible edition of Sevilla, 1496, and later Zaragoza: Jorge Coci, 1508 (Bibliografía n. 632)

- Primaleón. Salamanca: [Juan de Porras], 1512 (Bibliografía n.1950)

- Lepolemo, el Caballero de la Cruz. Valencia: Juan Jofre, 1521 (Bibliografía n.1813)

- Amadís de Grecia. Cuenca: Cristóbal Francés, 1530 (Bibliografía n.1426). Since the inscription reads “el de | gaula y grecia”, it may be assumed to refer to this 9th book of the Amadís cycle: El noveno libro de Amadís de Gaula, que es la crónica del muy valiente y esforçado príncipe y cauallero de la Ardiente Espada Amadís de Grecia.

- Florisel de Niquea (Parts I-II, 10th book of the Amadís cycle). Valladolid: Nicolás Tierri, 1532 (Bibliografía n. 1458)

- Belianís de Grecia (Parts I-II) Sevilla 1545, now lost; Burgos: Martín Múñoz, 1547 (Bibliografía n.1505)

- Espejo de príncipes y caballeros (El Caballero del Febo) (Part I). Zaragoza: Esteban de Nájera, 1555 (Bibliografía n. 1672)

Other romances and works are mentioned in the inscription.

- Libro de esforçado cavallero conde … Partinoplés. Burgos: Arnao Guillén de Brocar, 1513 (Pascual de Gayangos, Libros de caballerías [Madrid, 1857, p. LXXXI])

- La crónica de los nobles caualleros … Tablante de Ricamonte y Jofre, hijo de Donasón. Toledo 1513 (Gayangos LXIII)

- La historia del rey Canamor y del infante Turián, su hijo. Sevilla: Jacobo Cromberger, 1528 (Gayangos LXXVIII) [recorded as 1509 in the Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC)]

- El verdadero suceso de la famosa batalla de Roncesvalles, con la muerte de los doze pares de Francia by Francisco Garrido de Villena, listed by Gayangos as Toledo 1583 (Gayangos LXXXVI); recorded in WorldCat, Valencia: Ioan de Mey Flandro, 1555 (OCLC: 7568633) and USTC

- Los tres libros de Mattheo Maria Boyardo [Orlando enamorado] Alcalá: Hernán Ramírez, 1577 (Gayangos LXXXVII; WorldCat documents Valencia: Ioan de Mey Flandro, 1555. [OCLC: 743612819]). The Italian original dates from 1482-83 for the first two books, and 1495 for the third.

- Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, Antwerp: Martin Nucio, 1549 (Gayangos LXXXVII). The Italian original dates from 1516, with the complete poem dating from 1532.

The “Orlando enamorado y furioso y | Roncesballes” of the ex-libris is ambiguous. It seems clearly to refer to Boiardo’s work, but it is uncertain whether the second reference is to both Ariosto’s Orlando furioso and Garrido de Villena’s Verdadero suceso de … Roncesvalles or to Ariosto’s Segunda parte de Orlando con la famosa batalla de Roncesvalles. In either case, the dating is much the same since the second part of Orlando furioso, in Spanish translation, was first printed in Antwerp: Martin Nucio, 1556, according to USTC.

The history of Africa mentioned is probably Pedro de Salazar’s Hystoria de la Guerra hecha contra la civdad de África. Con la destruyción de la villa de Monazter, & Isla del Gozo, y pérdida de Tripol de Berberia. According to J-Ch. Brunet, Salazar’s work appeared in Naples, by Maistre Matia, on 20 January 1552 (Manuel, Vol. 2, Paris, 1880, col. 571).

As PhiloBiblon notes, the dating of these texts would place the writing of the inscription after 1555/56 at the earliest, since the Caballero del Febo, Roncesvalles, as well as the translations of Boiardo’s and Ariosto’s works, date from those years.

By the 1580s the chivalric texts were falling from favor as a literary form, as the diminishing number of editions and titles suggest. Eisenberg and Marín Pina (458-59) document the first editions of the Hispanic romances as spanning from ca. 1496 through 1587, then the Policisne de Boecia appeared in 1602. Since the handwriting of the inscription dates from the end of the 16th century, and the writer speaks favorably of the romances, the ex-libris probably was composed not much later than the 1590s or early 1600s; and if it is by Suero de Quiñones (n. 3), then, by definition, before 1590.

These remarkable inscriptions penned on the last printed folio of Lucena’s Diálogo de vita beata provide an extraordinary glimpse into the ownership of the book and the literary tastes of Suero de Quiñones, whoever he may have been.

All images are taken from the digital facsimile of Inc. 3, courtesy of the Biblioteca de Castilla – La Mancha.

Ivy A. Corfis

University of Wisconsin, Madison