In the 16th century, Western European Renaissance cartographers treated the Ukrainian lands as a peripheral place. Initially, Ukraine’s territory appeared only on maps that covered much larger geographical frames, such as Central Europe, Eastern Europe, or the Black Sea region. These early maps still privileged classical sources which had provided descriptions of the area, notably Herodotus, who had authored a detailed account of the Scythian lands north of the Black Sea. Other classical authors, including Ptolemy, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Tacitus, covered a later period when the Sarmatians, a confederation of Eastern Iranian nomadic peoples, moved westward and, by 200 BCE, began to dominate the Scythians. Their control of the Pontic Steppe brought the Sarmatians into contact with Greek and Roman communities.

In 1477, Dominicus de Lapis published the first illustrated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, translated by the humanist Giacomo d’Angelo da Scarperia, in Bologna, Italy. Its 26 plates, which had been engraved by Taddeo Crevilli of Ferrara, included the map “European Sarmatia,” the first printed map to cover Ukrainian territory. The prestige of Ptolemy’s Geography meant that the sheets showing “European Sarmatia” and “Asian Sarmatia” continued to be standard fare for some time.

Sebastian Münster (1489-1552), Lutheran theologian, Hebrew scholar, mathematician, cartographer, and cosmographer, published four editions of Ptolemy’s Geography in his lifetime. His Geographia universalis vetus et nova (1540), printed in Basel, Switzerland, included “Tabula Europae VIII,” a map of Eastern Europe in trapezoidal form with pictorial relief, essentially Münster’s version of the sheet “European Sarmatia.” All geographical names on this map are drawn from the classical sources which Renaissance scholars prized. Rivers which dissect the Ukrainian lands are thus identified as Tyras (Dniester), Hypanis (southern Bug), Borysthenes (Dnipro or Dnieper), and Tanais (Don).

However, Münster’s 1540 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography did not contain just the Ptolemaic maps. It also featured 21 modern maps, which Münster himself had produced. Münster subsequently added new plates each time he issued a revised edition of his Geographia universalis. The 1552 edition also featured a contemporary map of Poland and Hungary, “Polonia et Ungaria, XX Nova Tabula,” based on information gleaned from the work of the Polish cartographer Bernard Wapowski (ca. 1450-1535). The Ukrainian lands west of the Dnipro (or Dnieper) River are here identified with regional labels as Russia, Volhinia, Podolia, Codimia, and Bessarabia.

Münster uses the geographical name Russia to identify the westernmost part of Ukraine, the lands of the Ruthenian domain of the Polish Crown, the Ruthenian Voivodeship. Historically this area was part of the territory of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (1199-1253) of the Kyivan Rus, and later the historic core of its successor, the Kingdom of Ruthenia (1253-1349). It was subsequently conquered by Lithuanians and Poles. Other Ukrainian lands west of the Dnipro River with Kyovia (= Kyiv) are shown as parts of Lithuania, within its yellow border. By contrast, the lands east of the Dnipro River are identified as Tartaria Precopien (Crimea) and Tartaria Minor, regions controlled by the Crimean Tatars. Moscovia appears in the upper eastern margin of the map, within the green border which demarcates the Tatar sphere of influence. It is shown as a territory which historically paid tribute to the Golden Horde.

The western Ukrainian cities of Leopol (Lviv) and Halitz (Halicz), important medieval centers, are shown in the left margin next to the geographical name Russia. Münster‘s Polonia et Ungaria, XX Nova Tabula thus identifies Russia as the territory of the Kingdom of Poland’s Ruthenian Voivodeship, which existed from 1434 to 1772.

In the right margin appears the emblem of the Golden Horde (also known as Ulug Ulus, literally “Great State” in Turkic), initially the northwestern part of the Mongol Empire, later transformed into a Turkicized khanate. In the 16th century “Tartaria” was controlled by the Crimean Khanate, a successor state of the Golden Horde. This is also a device that enbles Münster to show that the Ukrainian lands were contested borderlands.

In 1618, after the Truce of Deulino, most Ukrainian lands were situated within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but social and political crises gradually eroded its power base. Other powers tried to assert control over parts of the borderlands, including Czarist Russia, the Austrian Habsburgs and the Kingdom of Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Crimean Khanate. Cossack hosts, self-governing groups of Eastern Slavic Orthodox believers, communities with military forces, grew in size, and more aggressively pursued their own interests, notably the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who established the Cossack Hetmanate.

In 1613, the geographical name “Ukraina” appeared for the first time on a printed map, Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae, caeterarumque regionum illi adiacentium exacta descriptio, in English translation The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Surrounding Regions with Their Exact Description. This celebrated wall map, commonly identified as the Radziwiłł (or Radvila) map, has a complicated publication history: About 1585 Prince Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł (1549–1616), also known as Mykalojus Kristupas Radvila, a powerful Lithuanian magnate, commissioned Maciej Strubicz (1530-1604), a notable Polish cartographer, to produce a map of the entire Lithuanian state. Radziwiłł saw a need for an accurate map, which could be used as an efficient planning tool for administrative and military matters. He was also interested in documenting the boundaries and heritage of the old Lithuania, which had been obliterated by the Union of Lublin (1569). The Union’s political settlement had created a single state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, both politically and culturally dominated by its Polish core.

Strubicz had served as secretary and geographer to Stephen Báthory, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. He had drawn an important military campaign map, which aided Polish and Lithuanian forces in the final stages of the Livonian War (1577-1582), when they faced off against the Muscovite army of Ivan IV “the Terrible.” Báthory managed to force a settlement which excluded the Grand Duchy of Moscow from access to the Baltic Sea. For his services, Strubicz was subsequently ennobled in Warsaw in 1583. This map covered Livonia, as well as parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. An improved version was published in Cologne, Germany, in 1589, by Marcin Kromer under the title Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae, Livoniae et Moscoviae descriptio.

Radziwiłł, who was nicknamed “Sierotka” [the orphan] to distinguish him from other members of the princely Radziwiłł family, served as Great Marshal of Lithuania (1579–1586) and Voivode of Trakai-Vilnius (1604–1616). He was a powerful man with connections and considerable means at his disposal. For years, he funded Strubicz’s work and provided support from others who gathered at Nesvizh Castle, the residential estate of the Radziwiłł family, today located in Niasviž, Belarus.

Strubciz’s diligent efforts greatly improved the mapping of this large section of Eastern Europe. He skillfully mined data derived from inventories, surveys, and terrain measurements. Many of these sources were produced during the Volok reform, a 16th-century land reform which led to an increase in crop yields and state revenue. The Volok reform strengthened the manorial system in Lithuania, but the reforms also reduced many Lithuanian peasants to serfdom. Land holdings were measured, divided into voloks, land units of about 52.8 acres, and entered into a cadaster, a detailed, official record of real estate boundaries, ownerships, and land values of a specific area.

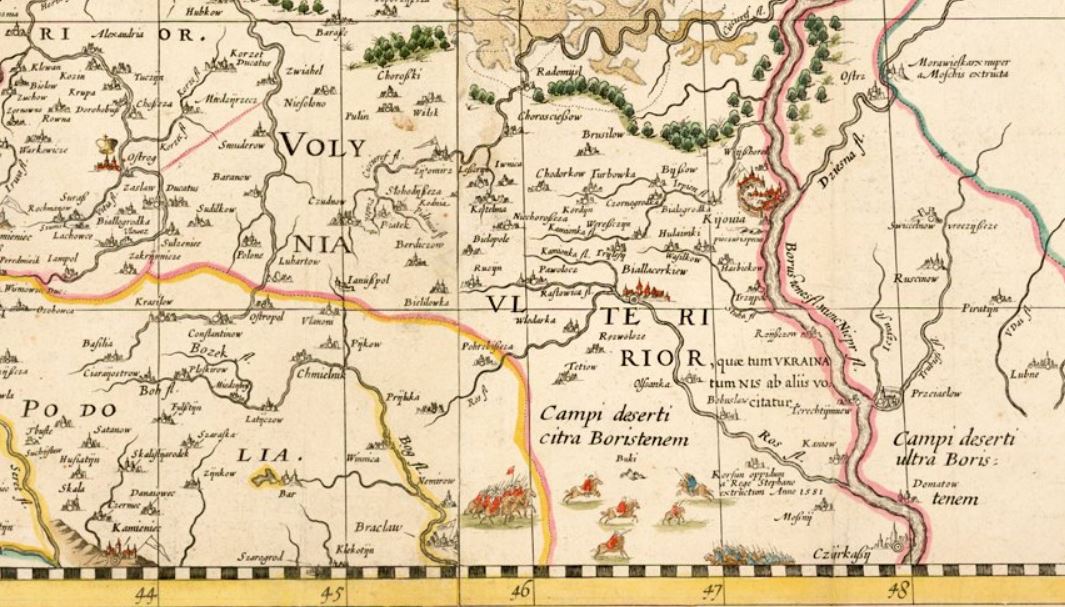

Roaming bands of Cossacks and Crimean Tatars are shown at the bottom of the Radziwiłł map of 1613, facing off against each other in the “deserted plains.” Historians like Bohdan S. Kordan, Steven Seegel, and Serhii Plokhy have long emphasized the central role Cossacks played in popularizing the geographical name Ukraine in the 17th century. Europeans identfied Ukraine as the “Land of the Cossacks.”

The map covers a vast region, stretching from Riga to Smolensk in the north, and from Cracow to Kyiv in the south. It locates 1,020 cities, towns, and villages, and very precisely maps water features throughout this vast region. It shows political and administrative boundaries, including a line which divides the ancient Grand Duchy of Lithuania in half and closely mirrors the present-day Ukrainian-Belarusian border. The region west of Kiova (Kyiv) is identified as “Volynia Ulterior, quae tum Ukraina tum Nis ab aliis volcitatur,” in English translation “Outer Volhynia, known either as Ukraine or as the Dnipro River Region.” The geographical name “Ukraina” thus describes part of the lands in the south, centered on the right bank of the Dnipro River. “Ukraina” roughly extends from Kyiv in the north to Cherkasy in the south. Strubicz identifies an area west of Cherkasy as wild steppe, “Campi deserti citra Boristenem,” in English translation “Deserted plains on this side of the river Borysthenes.”

Also included are historical notes and explanatory text, compiled by Tomasz Makowski (1575–circa 1630), a printer, artist, and engraver, who worked at the court of Prince Radziwiłł at Nesvizh Castle and also played an important role in preparing the map for publication. The English Jesuit mathematician Jacob Bosgrave was also a contributor. The Voivode of Kyiv, the Ruthenian Orthodox magnate Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski (also known as Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozkyi) and Józef Wereszczyński, Catholic bishop of Kyiv, provided cartographic data about the Ukrainian lands.

Prince Radziwiłł now contacted the Dutch map publisher Willem Janszoon (Blaeu) (1571–1638), famous for the manufacture of globes and wall maps, for publication of his map. Hessel Gerritsz (1581–1632), a Dutch cartographer of Blaeu’s publishing house in Amsterdam, engraved the plates, and, in 1613, Blaeu published the wall map in four sheets, under the imprint “Guilhelmus Janssonius.” He also published a related strip map of Ukraine’s Dnipro River region from Cherkasy to its Black Sea estuary on two additional sheets. Following the course of the river, the map describes the Dnipro rapids, local salt mines, towns and villages, and fortifications, and also includes notes about Cossack traditions. Blaeu eventually emerged as a noted publisher of atlases, and featured the Radziwiłł map in his Appendix Theatri A. Ortelii et Atlantis G. Mercatoris, continens tabulas geographicas diversarum Orbis regionum, nunc primum editas cum descriptionibus in 1631. The map subsequently appeared in other atlas editions through 1670.

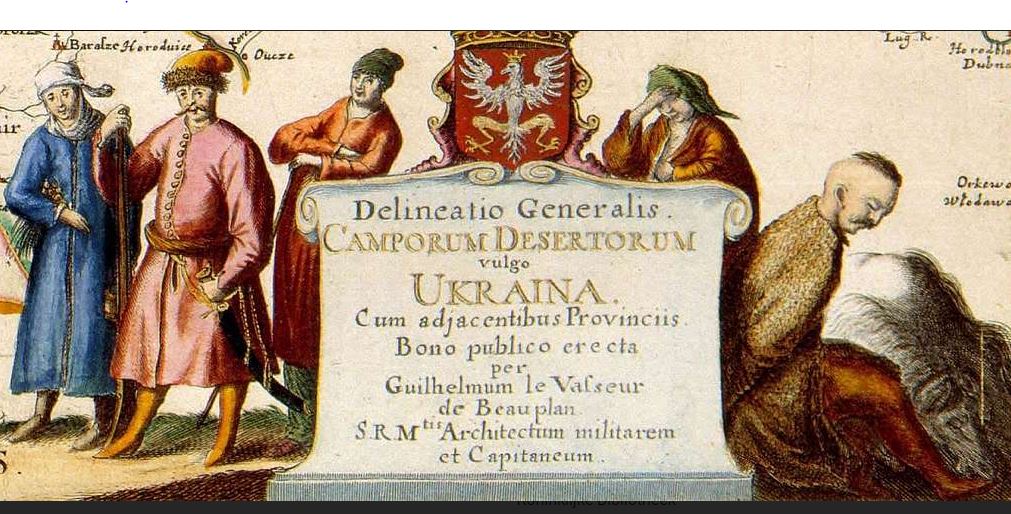

One cartographer who recognized the significance of the Radziwiłł map was Guillaume le Vasseur de Beauplan (1600-1673), a French military engineer, who served for two decades in the army of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, starting in 1630. Beauplan was initially charged with identifying suitable sites for the construction of fortifications in Ukraine. Later he planned settlements, and built or enlarged fortresses. Beginning in 1648, Beauplan turned his attention to the map trade. He published a general map of Ukraine, in 1650 followed by a special map of the same area on eight sheets, engraved in the workshop of the Dutch cartographer and map publisher Willem Hondius (de Hondt) in Gdansk.

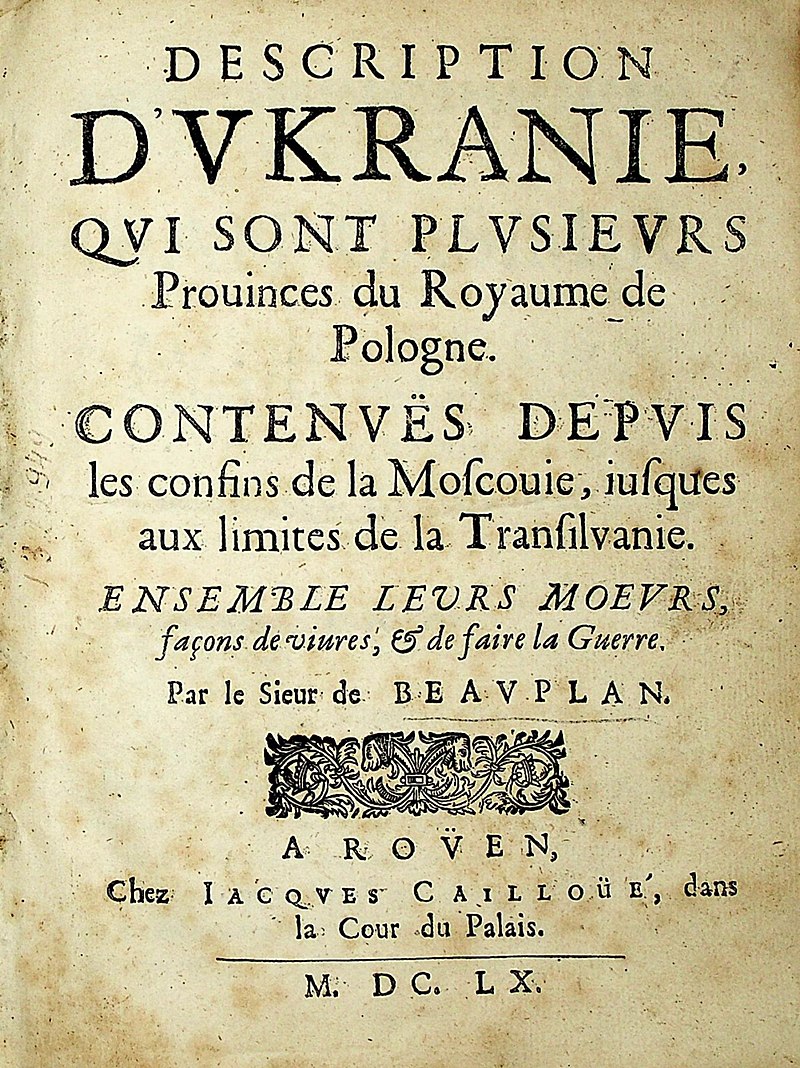

In 1660, the Carte d’Ukranie, contenant plusieurs provinces comprises entre les confins de Moscovie et les limittes de Transilvanie, a Beauplan map published in Rouen, France, by Jacques Cailloue, boldly demarcated the boundaries of Ukraine. That same year Cailloue also published a second, enlarged edition of Beauplan’s popular Description d’Ukranie (Rouen, 1660). A third edition followed in 1661. In his writings and on his maps Beauplan carefully noted the geographical naming practices of the inhabitants of the Ukrainian lands. His decision to identify the vast region located between Transylvania and Muscovy as Ukraine reflects 17th century Cossack usage.

Beauplan’s maps were subsequently incorporated in Blaeu’s Atlas major (1659-72) and appeared in the 1680s in influential atlases published by Johannes Janssonius and Moses Pitt. Other cartographers now treated Beauplan’s work in Eastern Europe as authoritative, and continued to see Ukraine as “Land of the Cossacks.” For the next century and a half cartographers faithfully reproduced Beauplan’s maps in atlas compilations. Beauplan thus played a crucial role in helping to codify the usage of the geographical name “Ukraine,” for a large defined territory.

Suggested readings:

Buczek, Karol. The History of Polish Cartography from the 15th to the 18th Century. 2nd edition. Amsterdam: Meridian Publishing Company, 1982.

Kordan, Bohdan S. Land of the Cossacks: Antiquarian Maps of Ukraine. Winnipeg: Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre, 1987.

Kordan, Bohdan S. The Mapping of Ukraine: European Cartography and Maps of Early Modern Ukraine, 1550-1779. New York: The Ukrainian Museum, 2008.

Magocsi, Paul R. Historical Atlas of Central Europe. 3rd edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Plokhy, Serhii. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. Revised edition. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

Plokhy, Serhii. “Placing Ukraine on the Map of Europe.” In The Frontline: Essays on Ukraine’s Past and Present, 15-36. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2021.

Seegel, Steven. Ukraine under Western Eyes: The Bohdan and Neonila Krawciw Ucrainica Map Collection. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2011.