by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

The pocket of Berkeley bounded by Telegraph and Shattuck avenues is generally considered to be quiet and uneventful. Colorful Victorian houses line the blocks, gray apartment complexes full of Cal students loom over sidewalks, and telephone lines crisscross over each other, dividing the sky into irregularly sized rectangles and diamonds. I spend a lot of time in this part of Berkeley. I have my favorite houses, my favorite trees, my favorite views in every direction. I have my favorite alleys and blocks and moments in its history. I can’t pick a single favorite former resident, but Zona Roberts is high on the list.

Zona existed in Berkeley as a mother before she existed here as a student. She lived with her sons Ed, Ron, Mark, and Randy in a pale green house she rented on Ward Street, a few blocks west of the hustle and bustle of Telegraph Avenue and a few blocks east of Shattuck. I often walk by her old house. It’s blue now, with red front steps, and it sits unassumingly behind a fence overgrown with flowers in the springtime. When Zona moved in, she had a ramp installed in the back to allow Ed to get inside. Ed Roberts, Zona’s eldest son and a political science major at UC Berkeley, was the first wheelchair user ever admitted to the school, and virtually nothing in the city was wheelchair accessible when he arrived on campus in 1962, including his mother’s home.

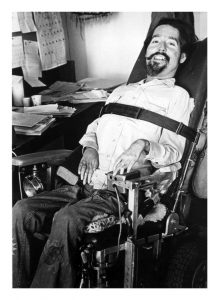

Ed Roberts

The green house, as it came to be known, acted as a sort of safe haven for the Roberts family and their friends. It was a family home for the community, not just Zona and her sons.

“It was a neighborhood of older families who’d lived there, a neighborhood of single-family homes, mostly, or two flats,” Zona said of the area, “The neighborhood was just changing as some of the older folks were dying off and some were moving away. A few younger people were moving in, but it was more or less an established neighborhood. But because of the racial composition and students in Berkeley, no one cared who went in and out of my house. The kids who came in or the Black students who visited and some lived, for a while, with me. There was no threat to their lives. There were none of those issues. It was just like a breath of fresh air to me. It was so nice not to have to worry about what might happen. I remember that vividly.”

Roberts Family

Zona, by all accounts, was an unflappable person. When she and her sons came to Berkeley, she was a recent widow, and had been Ed’s primary caretaker since he contracted polio and became a quadriplegic in 1953. She was a fierce advocate for all her sons and their needs and disliked being told what to do—she, as a learned expert in their likes and needs, felt that she knew best.

UC Berkeley promised a new world of opportunity for both her and Ed, when previously, his disability had meant neither of them was optimistic about what the future would hold, and her role as mother and caretaker left little room for imagining a life outside their home. But Berkeley was different; here, Ed was a student and leader, and eventually, so was she. In her oral history, when the conversation veered away from her time in Berkeley, she’d direct it back with references to the green house. The landscape of her college experience seemed to define it. She became acquainted with Berkeley alongside and behind Ed.

“One of the first days when I had taken Ed across and through campus, he was in a pushchair those days. He was quite tall and quite thin. We were going down into Faculty Glade and I had a hold of the back of his chair. It began to slip a little bit and I ran into a tree sort of deliberately to stop the chair, just the side of it, into this tree because I felt I was going to lose it. I don’t know whether my hands were sweaty, or the place was wet or what was happening. I think I finally learned how to do it backwards, where I’d walk down the hill backwards. I had better control.”

This anecdote, in my mind, speaks to the essence of Zona Roberts: ever present and adaptable to the needs of her son, caring and thoughtful, in the heart of Berkeley.

“In my senior year, I’d visit Ed up at Cowell. I remember one of the first times I walked through campus carrying my books, walked by Strawberry Creek, walking up to Cowell instead of coming in the station wagon from home or coming over to visit them. Here I was walking across campus on my way between classes and going up to visit and smiling a broad smile that I was now a student at Berkeley, also, and very proud of myself, and loving the campus and Strawberry Creek coming down through the middle of it. There’s some beauty in that Berkeley campus,” she said.

This feeling of reverence for Berkeley—for the atmosphere of casual intellectualism, for the exciting possibilities of being a student, for the sometimes-unbelievable natural beauty of the campus—is one I am intimately familiar with. I can only imagine how those feelings would be magnified for Zona, who, as a middle-aged widow and mother of four, never thought she’d live in Berkeley or become a student.

Zona was immensely proud to be a Berkeley student and to be Ed’s mother. She encouraged his involvement in activism and saw herself as an important backer of the disability rights movement; she saw herself as, first and foremost, an important backer of Ed.

“I saw my role at the office [UC Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living] as it became known as I did in Ed’s life, pushing Ed in front and being behind him,” she said of her involvement, “This was a place for people with visible disabilities to be visible, to be out in front. I found myself being in a supporting role, seeing that the office functions were going as smoothly as possible, seeing that there was food and heat and counseling and open doors and open access to information from us to the university and from the university to us. But somehow, we were in this together and it was a part of a wonderful movement. The time had come, and we were in the forefront of the movement and we were told this from all over the world. That was a glorious feeling. Hard work and glorious feeling.”

Zona Roberts

Zona Roberts worked hard to be the best mother she could be. Eventually, that meant becoming an integral part of a movement that was so much larger than any of them individually. If Ed Roberts was the father of the disability rights movement, Zona was the grandmother. She worked in the Center for Independent Living for years after its founding, and remains active in disability rights activism today, years after Ed’s death and well into her one hundred and first year of life.

I imagine the learning process of her activism was similar to learning to walk down the hill next to the Faculty Glade backwards, or modifying the old green house on Ward Street to make it accessible: sometimes slow-going, and certainly not without error, but always more than worth the trouble.