George Leitmann: Engineering Science, Risk, and Relationships at UC Berkeley and Beyond

The Oral History Center is proud to announce the launch of the oral history of UC Berkeley engineering scientist and Professor Emeritus George Leitmann. This is a large oral history, twenty-three hours of recording. From February 12, 2018 until February 12, 2019, Dr. Leitmann and I spent eleven sessions at his home talking about everything from his childhood in Vienna to Adolf Hitler and Sigmund Freud— both of whom he saw up close—to reconnaissance during World War II, rocket science, UC Berkeley administration, the riots at Berkeley in 1969, mathematics, the evolution of science and engineering instruction, the importance of family, and the kindness of dogs, among many other subjects.

Clearly, the sheer density of his life, including over a half-century of service as a professor and an administrator at UC Berkeley, demands this size of oral history. Another reason to go into such depth is that we look to individual narrators as witnesses to complex historical events. We want them to speak about what they have seen, experienced, suffered, and accomplished. We want them to tell us something about the seemingly inexplicable, the invisible, or even the conventional and overdetermined.

What do you learn when things fall apart? One of the themes that emerged clearly before we started filming at the beginning of 2018 was risk. George Leitmann’s life until the age of twelve or so had been pretty idyllic.

Then everything got turned upside down, and a young boy had to become a man very quickly. The coming catastrophe seemed highly improbable in the prosperous and stable Vienna of the 1930s. His elders told him so. They joked about it. Then he saw the man that everyone was talking about ride triumphantly into town, and he saw the other boys marching with crisp uniforms that had been brought in on trucks or out of hiding. His home was stolen and his family were split apart.

With the adaptability of youth, Dr. Leitmann escaped with some of his family to New York, where he developed a new version of stability and relative happiness. But he turned again to a world of danger by joining the US Army combat engineers in World War II. Combat engineers rebuild bridges and roads destroyed by a retreating army, and Leitmann performed reconnaissance for the engineers. In other words, he was in front of the group that was in front of an advancing army, often behind enemy lines, witnessing again and again the fates of the less fortunate. Risk.

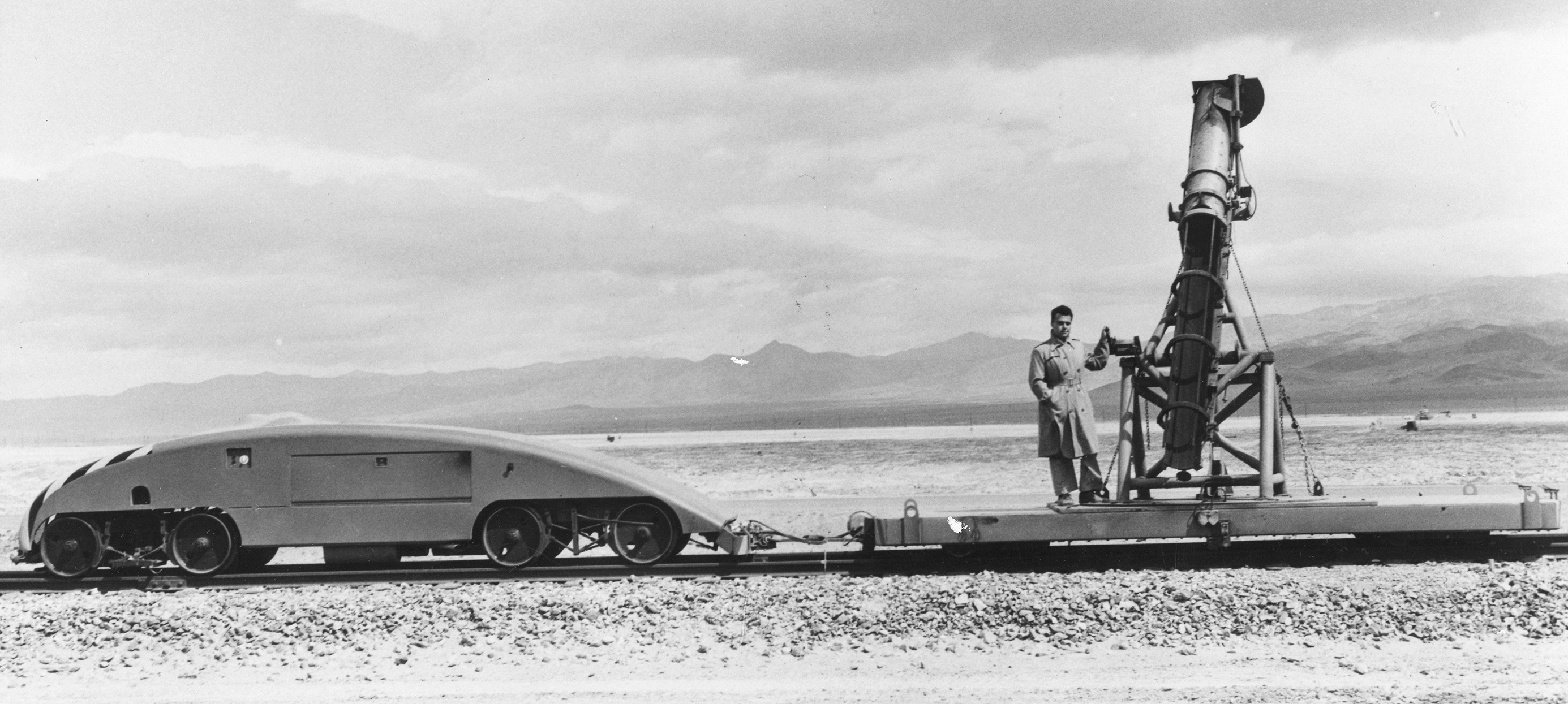

The history of science focuses on the relationship between the social and the technical. We study the institutions, the people, and the politics that make knowledge. It has seldom been so clear to me the relationship between a scientist’s lived experience and their research. After the war and a master’s degree in physics, Dr. Leitmann was recruited to work on the theoretical foundations of rocket research for the US Navy. He turned this experience and knowledge into seminal contributions to something called control theory, basically the mathematical rules that govern a system in a defined state of optimality or stability. This sounds very abstract, but Leitmann’s research ends up being used in rockets, economics, fisheries management, seismic stabilization, management of wind shear in aircraft, artificial intelligence, and many other areas. Many of our society’s systems are organized around probability, what is most likely to happen or not happen. There is a danger in this design that Dr. Leitmann has lived before. One key element of his life’s work is to account and control for highly improbable and catastrophic threats to a system, any system. But this seemingly theoretical research trajectory was informed by visceral experiences of danger and catastrophe. This was one of the most striking themes of these interviews: plan for the improbable and the terrible. Don’t look away.

guys, because here my father was still missing.”

Finally, and because of all of the above, we want narrators of these long life histories to be wise. When I asked Dr. Leitmann to be wise, he would usually shrug and say he was no expert, even when he was. So that was itself a piece of wisdom: be humble. We are not so much individuals as people who stand and fall by our communities. When we were planning our interview sessions together, I was constantly trying to get a handle on the vast range of his research interests, or to understand how to approach the monumental and global tragedies to which he was an important witness, and Dr. Leitmann would always come back to people. Did he mention this person? Did he give enough credit or time to that person? Other people matter. Family matters. Family is bigger than family. Other people first. This is his way of living, and his secular way of repairing the world, about whose broken state he always worries. And this is one reason Dr. Leitmann and I both suspect he has been so celebrated and decorated by his peers, his colleagues, his country and many others. He stands as an example of how to move through difficult times and face problems without being consumed by them, to reach a state of gratitude and qualified happiness for the complicated gift of being part of something grander than oneself.

The Oral History Center wishes to thank Richard Robbins for a generous contribution that made this project possible.

Paul Burnett, Berkeley, CA, 2019