Thanksgiving is almost upon us. And you know what that means.

That’s right: It’s pie season. After all, mustering up the mental fortitude to feast alongside that obnoxious out-of-town uncle you see once a year should be rewarded with a decadent dessert, right?

We think so.

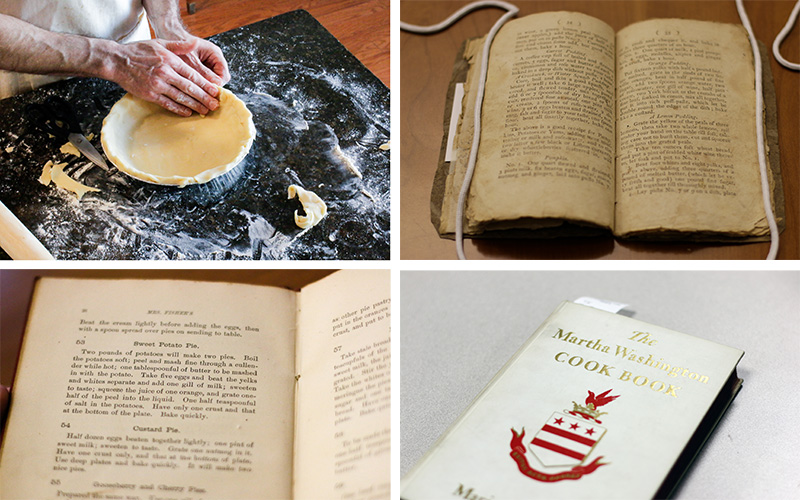

So we turned the clock back — way back — by baking and taste-testing three historical pie recipes from our collections to see if they would satisfy the modern palate.

The three recipes we chose come from books published in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries — well before Pinterest and the advent of the celebrity chef. That’s right — you won’t find Rachael Ray’s or, heavens forbid, Paula Deen’s names on any of these recipes.

Instead you’ll find three distinct, delectable desserts, each one holding its own historical significance — and each giving you a taste of the Library’s offerings and even, perhaps, baking inspiration for Thanksgiving.

A holiday classic

We started with the grandaddy of them all: pompkin pie. That’s no typo — “pompkin,” it turns out, is an old-timey way of saying “pumpkin.” And no Thanksgiving would be complete without this holiday favorite.

The recipe comes from The Bancroft Library’s second-edition copy of American Cookery — one of about 900 cookbooks in Bancroft’s collection. It’s a modest-looking volume, published in 1796, that came to Bancroft within the past decade or so.

“It came in, and no one realized the significance of it,” said David Faulds, curator of rare books and literary manuscripts at Bancroft.

The book packs historical significance: It is the first known cookbook written by an American. “It was the standard American cookbook,” he notes.

It’s also incredibly rare.

Just how rare is it? Well, Bancroft’s copy is believed to be one of five or six copies in the world. After living a quiet life at the Northern Regional Library Facility in Richmond, it now is kept in Bancroft’s vault and was recently featured in New Favorites, an exhibit highlighting recent additions to Bancroft’s major collections.

But let’s cut to the chase: How does this pompkin pie actually taste?

To find that out, we put the pie in front of a tasting panel including Faulds and four students (full disclosure: All are avowed pie fans) whose majors — and opinions — ran the gamut. All in the name of research, of course.

“It doesn’t taste quite modern,” one taster said, noting the lack of cloying sweetness.

It does, however, contain many of the hallmark pumpkin pie spices — nutmeg and ginger, among them — which have become ubiquitous in recent years. (Pumpkin pie spice potato chips, anyone?)

Perhaps the most notable difference is the lattice crust on top, which is absent in commonly used pumpkin pie recipes today.

But would the pie hold its own alongside more modern fare?

That’s a resounding yes, according to our panel.

Another classic — with a twist

Next up is another holiday staple: Sweet Potato Pie.

Like the pompkin pie, this one tastes familiar. But it also has an unexpected, zippy twist.

“I like the tang it has to it,” a taster said. “I’ve never had that in a pie.”

One panelist said it tasted like pumpkin and orange, while another swore it was carrot and lemon. (The “citrus-y” taste they noticed actually comes from orange juice and zest.)

The recipe traces back to What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, from 1881 — copies of which are held at both Bancroft and the Bioscience & Natural Resources Library.

Written by a former slave and plantation cook who moved from Mobile, Alabama, to San Francisco, it is thought to be one of the first cookbooks written by an African American. (It was believed to be the first cookbook written by an African American until the rediscovery of Malinda Russell’s Domestic Cook Book, published in 1866.)

And it was award-winning, too: At the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Fair in 1880, it won awards for best pickles and sauces as well as best assortment of jellies and preserves. (The author ran a pickle business.)

According to a later edition of the book, the namesake Mrs. Fisher — Abby Fisher — didn’t know how to read or write. Instead, she dictated the recipes to a group of prominent San Francisco and Oakland residents.

Of all the recipes, the terminology in this one had us scratching our heads the most. We felt that we could safely assume that a “cullender” was a colander. And “yelks,” it seemed, clearly referred to “yolks.”

But what is a “gill” of milk?

It turns out, it’s an antiquated measurement equaling half a cup — and does not, as one taster guessed, involve filling a fish with milk.

Presidential treatment

Then there’s the Quince Pie.

This one comes from the family cookbook of our very first first lady, Martha Washington. That’s right — move over, Melania Trump.

A quince, if you’re not familiar, is a yellow fruit that looks like a pear but tastes like a “woody apple,” as one taster put it.

A note: We’re using the word “pie” loosely here, because, although it looked beautiful in the pie tin, our attempts to cut it turned it into a crumble. That combined with the reddish tint of the cooked quinces seemed to confuse our tasters — and the resulting presentation looked almost gorey.

“It looks like body horror,” as one taster subtly (yet accurately) put it.

Other responses included that it looked like rhubarb, grapefruit, papaya, or even sashimi.

Though the texture was firm, the tasters agreed the pie was better than it looked, with at least one panelist declaring it the best of the bunch.

The recipe comes from 1940’s The Martha Washington Cook Book, adapted from Washington’s family cookbook. It’s one of the more than 5,000 cookbooks housed at the Bioscience & Natural Resources Library.

Notably, it’s the only recipe we tried that includes exact measurements. According to Faulds, the old practice of omitting measurements was actually quite common.

“That was the standard,” he said. “They assumed we knew what we were doing. They weren’t thinking about 200 or 300 years later.”

The recipe is straightforward enough, with the filling calling for just three simple ingredients: sugar, water, and quinces.

The pie, once ready, can be topped with whipped cream, but, as the recipe sternly notes, “Martha Washington did not do this.”

But this is not the time for holding back. Go ahead and pile on some whipped topping, and enjoy. After all, Thanksgiving happens only once a year.

Martha Washington would understand.

Note: We used recipe No. 1. This recipe refers to other recipes that can be found in the digitized version of “American Cookery,” found here.

No. 1. One quart stewed and strained, 3 pints cream, 9 beaten eggs, sugar, mace, nutmeg and ginger, laid into paste No. 7 or 3, and with a dough spur, cross and chequer it, and baked in dishes three quarters of an hour.

No. 2. One quart of milk, 1 pint pompkin, 4 eggs, molasses, allspice and ginger in a crust, bake 1 hour.

From: American Cookery, 1796

Two pounds of potatoes will make two pies. Boil the potatoes soft; peel and mash fine through a cullender while hot; one tablespoon of butter to be mashed in with the potato. Take five eggs and beat the yelks and whites separate and add one gill of milk; sweeten to taste; squeeze the juice of one orange, and grate one-half of the peel into the liquid. One half teaspoonful of salt in the potatoes. Have only one crust and that at the bottom of the plate. Bake quickly.

From: What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking, 1881

8 quinces

1 ¼ cup sugar

1 ½ cups water

Pastry

Wash the quinces. Cut in quarters, remove cores, and peel. Put in a pan together with one cup sugar and water, and let stew very slowly until tender. Turn fruit often. Line a pie plate with pastry and arrange the quinces in it in a neat design. Pour on the syrup and sprinkle with remaining one-fourth cup sugar. Lay criss-cross pieces of pastry on top and bake until a golden brown. The top pastry may be omitted and the pie covered with whipped cream before serving. Martha Washington did not do this.

From: The Martha Washington Cook Book, 1940