Sibeko-Kouate was born into a middle-class family in San Leandro, California on July 1, 1926. Her father, Turner Smith, worked for Calvert Distillers Corp., and her mother, Willette Smith, was active in many African American social clubs and fraternal orders. Sibeko-Kouate grew up in South Berkeley and graduated from Berkeley High in 1947. In the early 1950s, she studied music and teaching at San Francisco State College and ran a small business (Harriet – Ceramic Creations) out of the home she shared with her mother. Sibeko-Kouate attended Merritt College from 1965-1968, where she studied business administration, real estate, and community planning. She received her BA in Black Studies and an MA in Education from Cal State Hayward in the 1970s. At Merritt, Sibeko-Kouate helped develop the Black Studies Department and was the first African-American person elected student body president.

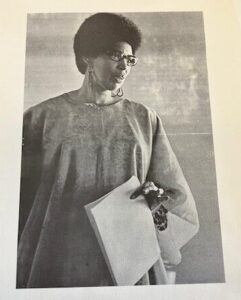

Here are three of the many faces of Sibeko-Kouate. On the left, posing with her ceramic creations, which she advertised on her business card as “hand made gifts to fit your personality”; in the center, pictured with colleagues who also advocated for the discipline of Black Studies and for Black Power: Sid Walton, Ruth Hagwood, and Nathan Hare; and on the right, teaching a class.

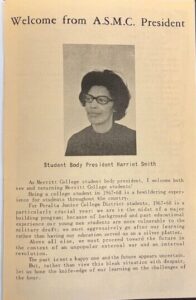

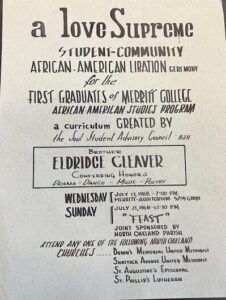

Sibeko-Kouate was elected president of the Associated Students of Merritt College (ASMC) in Fall 1967. In her welcome address, she notes that “Being a college student in 1967-68 is a bewildering experience…we must proceed toward the future in the context of an unpopular external war and an internal revolution…education should be a maker of a virgin future rather than a slave to an unjust and shopworn past. YOU CAN CHANGE THE WORLD!” Students like Sibeko-Kouate, and faculty, like Walton, sought to change the world by advocating for an African-American Studies Program at Merritt. The flyer on the right advertises a student-community ceremony to celebrate the first graduates of that program.

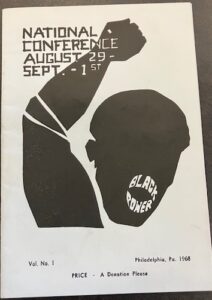

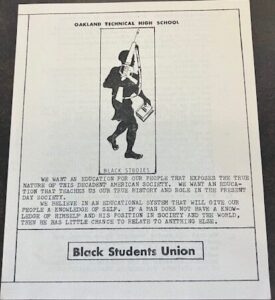

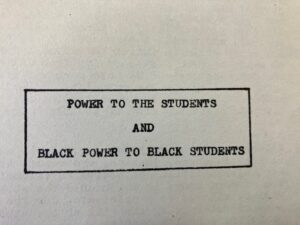

Sibeko-Kouate’s influence went beyond Merritt College. She also served as the President of the National Black Student Union and, in 1968, ran an education workshop on student-community relations for Black students on white campuses at the National Black Power conference in Philadelphia. Sibeko-Kouate’s papers contain materials related to Black curricula and Black Student Unions from many schools in California and, especially, the Bay Area. Examples include a brochure from the Black Students Union at Oakland Tech (in the center and on the right).

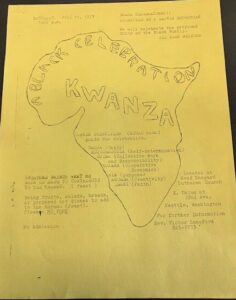

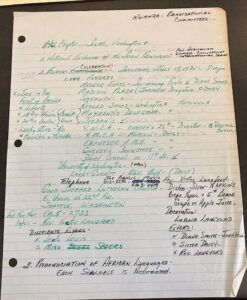

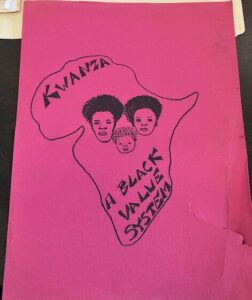

Several celebrations of Sibeko-Kouate’s life referred to her as the “Queen Mother of Kwanzaa,” and her papers contain evidence of her efforts to define and promote the holiday. Examples include these flyers and her notes from an Organizational Committee meeting in Seattle. (Most documents in the collection spell the holiday “Kwanza.” That is the original spelling of the African harvest festival on which the celebration is based. According to the American Heritage Dictionary, a seventh letter was added to correspond with the seven African principles honored during the holiday. Both spellings are correct.)

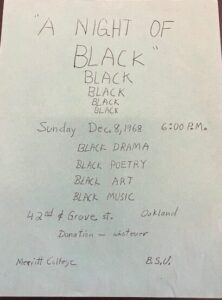

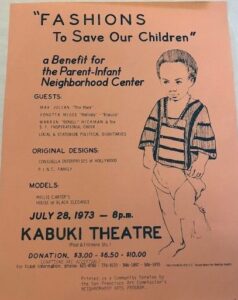

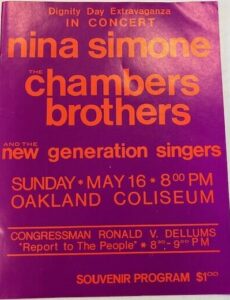

Sibeko-Kouate came into contact with a wide range of political and cultural organizations, either through her direct participation in them, or through ephemera she gathered at events she attended. The materials she collected document decades of African-American cultural life in the Bay Area, including visual arts, music, dance, theater, film, poetry, books, fashion shows, cultural festivals, sporting events, and the culinary arts. Events ranged from the very local (a night of entertainment at Merritt College), to benefits (for the Parent-Infant Neighborhood Center), to appearances by well-known performers and politicians at community events (Nina Simone, the Chambers Brothers, and Congressman Ron Dellums) . The fact that Sibkeo-Kouate collected these flyers and programs reflected her awareness of their historical significance.

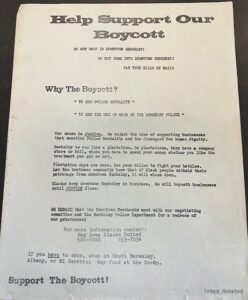

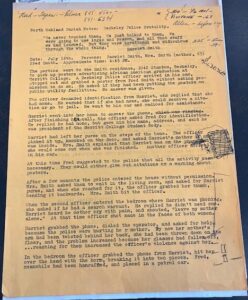

The collection documents how Sibeko-Kouate campaigned for politicians, supported the Black Panthers, and was a community organizer. The buttons on the left reflect her politics, the flyer in the middle asks residents to support a boycott to end police brutality, and the notes on the right document a July 1968 incident when Berkeley police assaulted Sibeko-Kouate and her mother after entering their home without permission. It’s not clear whether the assault motivated the boycott or was just another incident of police brutality in the Black community – but the cause of the organizers was very clear: “Our cause is Justice. We reject the idea of supporting businesses that sanction Police Brutality and the disregard for human dignity…Berkeley is run like a plantation…Plantation days are over. Use your dollars to fight your battles…Blacks keep downtown Berkeley in business. We will boycott businesses until JUSTICE flows.”

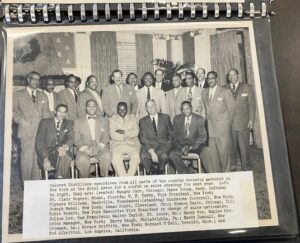

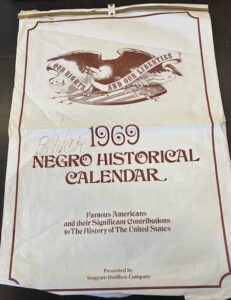

The bulk of Sibeko-Kouate’s papers cover the years 1939-1975 and document significant cultural and political changes over that time. The album on the left is from a 1953 Calvert Distillers gathering that Sibeko-Kouate’s father Turner attended. The meeting “represents the first time any industry gathered its men covering the Negro market from all over the country to meet in New York with its top executives for a two-way exchange of ideas on business.” The gathering included a testimonial dinner honoring Thurgood Marshall. Tubie Resnki, an Executive Vice President, said “This trip is another leaf in the Calvert book of leadership in interracial affairs.” A 1969 calendar produced by Seagram Distillers, Calvert’s parent company (on the right), celebrates “Famous Americans and their Significant Contributions” to the history of the United States. Someone (presumably Sibeko-Kouate) crossed out the outdated/offensive term “Negro” and replaced it with “Black.” This item’s contrast with her father’s souvenir from the early 1950s captures a cultural and political shift in rhetoric that can be seen throughout the collection.

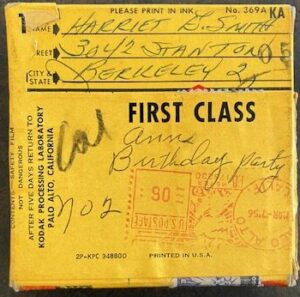

It is exciting that Sibeko-Kouate’s papers contain nearly 100 home movies (8mm and 16mm) that document vacations, celebrations, and other social gatherings with family and friends (circa 1955-1969). These films, like the Calvert album, other photographs, personalia, and family papers in the collection document the everyday lives of middle-class African Americans in the 20th century. (Please note: the films are not currently available for viewing.)