Tag: “The Languages of Berkeley”

Biblical Hebrew

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

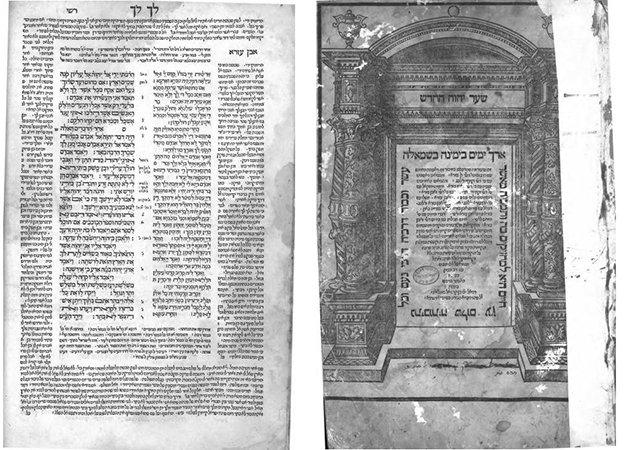

שער ה’ החדש

“The new gate of [the house of] the Lord.”

The son of an Antwerp merchant, Daniel Bomberg (born c. 1480) came to Venice to pursue the family business, and, having obtained a license to print Hebrew books, established a printing house. Among Bomberg’s first imprints were a Hebrew Pentateuch (1516) and the first Rabbinic Bible (1517).

The Rabbinic Bible was a new printed form, presenting the Hebrew text with full vowel and cantillation marks, and accompanied by Aramaic Targums and medieval commentaries. The four-volume second edition was produced by Bomberg in 1524; edited by Jacob ben Ḥayyim ibn Adonijah and containing an impressive critical apparatus of Masoretic notes, the second Rabbinic Bible has been the prototype for Hebrew Bibles to the present day.

The image of an ornate edifice fills the title page of volume one; between its decorated pillars, at the entry way, is a description of the book’s contents. Title page images such as this one—often accompanied by the phrase, “this is the gateway to the Lord,” from Psalm 118:20—establish the text as a place: a sacred place to be entered with care. Yet here, above this particular doorway, a somewhat different text (from Jeremiah 26:10), declares this to be “the new gate [of the house] of the Lord.” However venerable the site, the Rabbinic Bible (its publishers indicate) constitutes a novel approach.

Indeed, the Rabbinic Bible was a product of its time, a period in which Hebrew printing flourished in Italy, a time in which Christian study of the Hebrew Bible fomented and shaped its publication. Yet the Rabbinic Bible also made palpable Jewish textual culture, in which study of the Hebrew Bible closely entwined it with translation, commentaries, and other texts.

UCB scholars—and scholars from around the world—can pore over the pages of the 1524 Bomberg Rabbinic Bible at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

Come delve into Hebrew at Berkeley:

Study Hebrew and Hebrew literature in the UCB Near Eastern Studies Department:

- Hebrew with Rutie Adler

- Modern Hebrew literature with Chana Kronfeld

- Hebrew Bible with Ron Hendel

- Rabbinic literature with Daniel Boyarin

Choose the undergraduate Minor in Hebrew.

Pursue advanced study in UCB’s Near Eastern Studies or Comparative Literature graduate programs.

Contribution by Ruth Haber

Judaica Specialist, Doe Library

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: שער ה’ החדש …

Title in English: [The Rabbinic Bible]

Author: Jacob ben Hayyim ben Isaac ibn Adonijah or Jacob ben Chayyim (c. 1470 – before 1538)

Imprint: Venice: Daniel Bomberg, 1524-1535.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Biblical Hebrew

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Northwest Semitic

Source: The Internet Archive

URL: https://archive.org/details/The_Second_Rabbinic_Bible_Vol_1

Other online editions:

- Vol. 2, [ The 1524-25 Second Rabbinic Bible – Vol 02 ].

- Vol. 3, [ The 1524-25 Second Rabbinic Bible – Vol 03 ].

- Vol . 4, [ The 1524-25 Second Rabbinic Bible – Vol 04 ].

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Shaʻar ha-Shem he-ḥadash : zehu shiʻur mah she-hidpasnu be-ḥibur ze … [Second Biblia Rabbinica]. Venitsiya: Daniyel ben Ḳarniʼel Brombergi, [1524-1525].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Azerbaijani (Azeri)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Azerbaijani or Azeri is the term that is used interchangeably for the language throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. It is also known as Azerbaijani Turkish and retains most of the traditional grammatical endings of the pre-Republican era Turkish language that was spoken in the Ottoman Empire. However, in a certain sense, it is also influenced heavily by the Persian vocabulary. The language is currently spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan that was a part of the Czarist Empire in the 19th century as well as in Southern Azerbaijan that is the part of modern-day Iran. In the Republic of Azerbaijan, the language script was changed several times. Currently the Latin script is used. The Iranian Azerbaijan continues to use Arabo-Persian script.

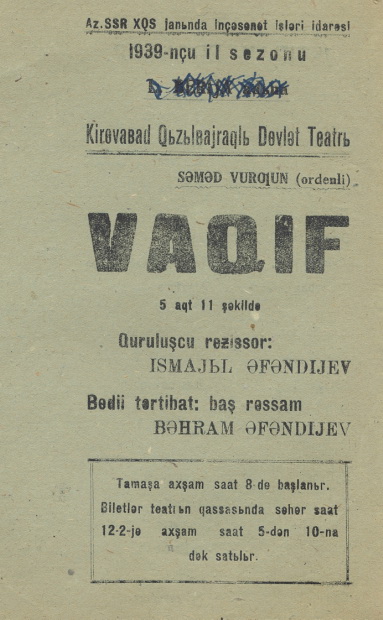

Samad Vurgun was a well-known Azerbaijani poet and playwright. The first work of Vurgun—the poem “Address to Youth”—was published in 1925 in the Tbilisi newspaper New Thought. Today every Azerbaijani schoolchild is familiar with his poetry. It is often set to music and performed by leading Azerbaijani artists. Featured in this entry is the play Vagif written in 1937 and which pays homage to the 18th-century Azerbaijani poet Molla Panah Vagif.

During his youth, Vurgun lived through the tough years of World War II. This challenging period had a very significant impact on his poetry, which was a real weapon against the enemy in that difficult time. He wrote over 60 poems on the theme of the Great Patriotic War. It was not an easy task, but in his works, the young poet managed to inspire an optimistic mood amongst the people, who were suffering from the hardship of war.

He was calling on people to be patient and hardworking to attain victory. Vurgun’s popularity grew during the propaganda campaign—leaflets with his creation “Ukrainian partisans” were dropped from planes over local forests to maintain the high spirit of the guerrilla fighters.

His poem “Parting Mother” was highly appreciated as the best anti-war work during a contest held in the US in 1943. It was published in New York and distributed to military personnel after it was selected among the best 20 poems of world literature about the war.

During World War II, Vurgun created poems dedicated to the deeds of Azerbaijanis in the fight against fascism. In the poems “Nurse”, “Bearer”, “The story of the old soldier”, “Brave Falcon”, and “Unnamed Hero”, he describes the selfless struggle against the invaders, the heroism of Azerbaijani soldiers and their contribution to the liberation of people from fascism. Due to his patriotism and unique talent, Samad Vurgun became a poet of the nation.

In 1943, Vurgun was awarded the title of Honorary Artist of Azerbaijan SSR. Two years later he was elected to the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. His works have been translated into many foreign languages. For many years, he headed the Azerbaijan Union of Writers, was repeatedly elected a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and Azerbaijan and was awarded many orders and medals. His early lyric poems were published only after his death, in a compilation called “Chichek” (“Flower”).

Living in the era of a communist dictatorship, Vurgun had to praise the regime in his works, but in spite of this, the creativity of Vurgun, the restrained style of his poems had a tremendous impact on the development of the Azerbaijani poetry. Samad Vurugn died in May of 1956 and is buried in the Alley of the Heroes in Baku.

The Azerbaijani Studies collections in the UC Berkeley Library represent the current research interests of our faculty and students. One of the well-known scholars of Caucasus Studies, Professor Stephan H. Astourian, interrogates the historical realities of Caucasus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in the context of the Armenian Genocide. The Azerbaijani collections are also supported through the donations of books by the Azerbaijan Cultural Society of Northern California. One prominent mathematics professor of Azerbaijani descent was Lotfi A. Zadeh. The focus of current collections on Azerbaijan revolves around the history of Azerbaijan and Caucasus, Armenian Genocide and the Frozen conflict of Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

Gadimova, Nazrin. “Samad Vurgun: A Poet With Pen as Sharp as Weapon,”AzerNews (May 28, 2013), (accessed 5/1/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: “Vagif” in Səməd Vurğun : Seçilmiş əsərləri.

Title in English:

Author: Vurghun, Sămăd, 1906-1956.

Imprint: Bakı : “Şərq-Qərb”, 2005.

Edition: n/a

Language: Azerbaijani (Azeri)

Language Family: Turkic

Source: Sabunchu District Central Library, Central Libraries of Azerbaijan

URL: http://sabunchu.cls.az/front/files/libraries/54/books/831431433401352.pdf

Other online editions:

- Vurghun, Sămăd, 1906-1956. Избранные сочинения в двух томах: перевод с азербайджанского. Translated into Russian by Pavel Antokolʹskiĭ. Moskva: Gosizdatel’stvo khud.literatury, 1958.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Vagif ; Mughan / Sămăd Vurghun. Baky: Gănjlik, 1973.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

The Promise of Multilingualism by Judith Butler

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“If we were only to work in English, we would misunderstand our world.

Monolingualism keeps us parochial even if the language we speak

has achieved global dominance.”

In her keynote lecture on Feb. 5 for the exhibit reception for The Languages of Berkeley, Judith Butler said that “At UC Berkeley and in this Library in particular, in language courses and in literature and history courses, students and faculty alike understand themselves to be part of an ongoing multilingual experiment—one that brings with it different histories and cultures, different ways of understanding the social world.” A world-renowned philosopher, gender theorist, and political activist, Butler is best known for her book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990), and its sequel, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’ (1993), which have both been translated into more than twenty languages. Her most recent book is The Force on Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind (2020). She has taught at Cal for 27 years in the Department of Comparative Literature and in the Program of Critical Theory, where she is Maxine Elliot Professor. Among her achievements, she is currently the 2020 president of the Modern Language Association, in which she is, in the words of Professor Rick Kern, “the lead advocate for languages in the United States.”

Butler’s lecture, “The Promise of Multilingualism,” eloquently put into words the inspiration for the exhibition itself. “In learning another language, we practice humility in an effort to gain knowledge and to live in a broader world—one that exceeds the national boundaries that too often divide us,” she said. “The passage through humility gives us greater capacity to live and think in a multilingual world, to shift from one way of knowing to another.” Her entrancing talk that winter evening in the iconic Morrison Library—which followed nine short readings by faculty, students, and librarians in different languages—echoed and expanded on some of the ideas in Who Sings the Nation-State?: Language, Politics, Belonging which she co-wrote with Gayatri Spivak in 2007.

At Berkeley, and in literature, history, and philosophy departments especially, “multilingualism is our location and it means that we never assume one language holds the truth over any other,” she said. By learning and working in other languages, she posited, we experience both dislocation and an enriching humility finding ourselves less capable in another language than the primary one that we speak. For some of us, for whom English is a first language, we have a promising experience that productively challenges the notion that English is at the center of the world. “Each and everyone of us speaks a language that is foreign to someone else,” she affirmed. “At least here, at least potentially what we call ‘the foreign’ is actually the medium in which we live together, the enigmatic basis of our worldly connection with one another.”

The Arts & Humanities Division of the UC Berkeley Library and the Berkeley Language Center (BLC) hosted the reception for the online exhibition. University Librarian Jeff MacKie-Mason gave introductory remarks, and Rick Kern, director of the BLC and professor in the Department of French, introduced the keynote speaker. Romance Languages Librarian Claude Potts, who is the lead curator for the exhibition, involving more than 40 contributors, moderated the event. Four of those who read short texts in their original languages also contributed to the online sequential exhibit, which launched in February 2019 and will reach completion this summer, with approximately 70 entries representing most of the languages that are currently taught and used in research at Berkeley.

Virginia Shih for Vietnamese (South/Southeast Asia Library) – 13:40

Curator for the Southeast Asia Collection

Ahmad Diab for Arabic (Department of Near Eastern Studies) – 17:08

Assistant Professor

Yael Chaver for Yiddish (Department of German) – 23:50

Lecturer in Yiddish

Jeroen Dewulf for Dutch (Department of German and Dutch Studies Program) – 31:30

Director, Institute of European Studies

Interim Director, Institute of International Studies

Queen Beatrix Professor

Sam Mchombo for Chichewa (African American Studies) – 38:58

Associate Professor

Deborah Rudolph for Chinese (C.V. Starr East Asian Library) – 48:31

Curator

Marinor Balouzian and Natalie Simonian for Armenian (Armenian Studies Program) – 53:21

Undergraduate Students

Emilie Bergmann for Spanish (Department of Spanish & Portuguese) – 58:19

Professor

Robert Goldman for Sanskrit (Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies) – 1:07:05

Catherine and William L. Magistretti Distinguished Professor

See also the Library News story “Want to explore a language? At Berkeley, the possibilities are (nearly) limitless.”

Or the blog post “We All Speak a Foreign Language to Someone” by Caitlyn Jordan for the Townsend Center for the Humanities.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

www.ucblib.link/languages

Norwegian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

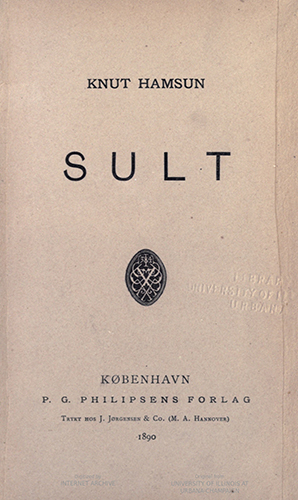

Det var i den Tid, jeg gik omkring og sulted i Kristiania, denne forunderlige By, som ingen forlader, før han har faaet Mærker af den . . .

It was in those days when I wandered about hungry in Kristiania, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set its mark upon him . . .

(trans. Sverre Lyngstad, 1996)

So opens Knut Hamsun’s novel, Sult (Hunger). When Sult was published in 1890, it represented a literary breakthrough not just in Scandinavia but also throughout Europe. Though Hamsun’s later novels would take more conventional forms, Sult was a harbinger of 20th century modernism for its stream-of-consciousness narration and its focalization of a vagabond figure who struggles to cope with modern urban life. The novel’s plot is spare: an unnamed—and unreliable—narrator arrives in Kristiania (now Oslo); he struggles to get work as a writer and has occasional run-ins with strangers; three months later, he leaves the city by boat. What makes the novel remarkable is how it portrays the inner life of a—literally—starving artist. Through the narrator’s increasingly wild musings, it is difficult for the reader to decipher whether the protagonist is insane or just hungry, and whether his hunger is forced upon him by poverty or voluntarily undertaken as part of a fascinating, yet ambiguous, creative project. As Hamsun put it elsewhere, Sult aims to reveal “the unconscious life of the soul.”[1]

Knut Hamsun is widely accepted as one of Norway’s greatest authors. He is second only to Henrik Ibsen in terms of international renown and he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1920 for his novel Markens grøde (“Growth of the Soil”). However, his legacy has been hotly debated, and his reputation severely damaged, by his strong Nazi sympathies and support of the Nazi occupation of Norway (1940-45).

Though Sult was written in Norwegian, it is a Norwegian highly inflected by Danish spelling. For 400 years, Norway was under Danish rule, during which time Danish was the language of writing and instruction in Norway. After declaring independence from Denmark in 1814, Norwegians were eager to establish an official language that better reflected the range of Norwegian dialects, but this has proven to be a long and contentious process. When Sult was published, Norway still had a shared publishing culture with Denmark, and, indeed, the first edition of Sult was published in Copenhagen.

Hunger has been taught in various courses at UC Berkeley in the Department of Scandinavian, including undergraduate courses on “place in literature” and “consciousness in the modernist novel,” as well as in graduate courses on affect and fictionality. The department, which is one of only three independent Scandinavian departments in the United States, also offers courses in beginning and intermediate Norwegian, a language spoken by more than 5 million people. In addition to the 1890 first edition of Sult, the UC Berkeley Library owns multiple English translations of this landmark work.

Contribution by Ida Moen Johnson,

PhD Student in the Department of Scandinavian

Notes:

- This phrase comes from the title of Hamsun’s 1890 essay, “Fra det ubevidste Sjæleliv.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Sult

Title in English: Hunger

Author: Hamsun, Knut, 1859-1952

Imprint: Copenhagen: P.G. Philipsens Forlag, 1890.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Norwegian

Language Family: Indo-European,

Source: The Internet Archive (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://archive.org/details/sult00hams/page/n5/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- Hunger. Translated from the Norwegian of Knut Hamsun by George Egerton, with an introduction by Edwin Björkman. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1935, ©1920. HathiTrust

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sult. København, P.G. Philipsen Forlag, 1890.

- Hunger. Translated into English by Sverre Lyngstad. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

- Hunger. Introduction by Paul Auster; translated from the Norwegian and with an afterword by Robert Bly. New York: Noonday Press, 1998.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Bengali

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

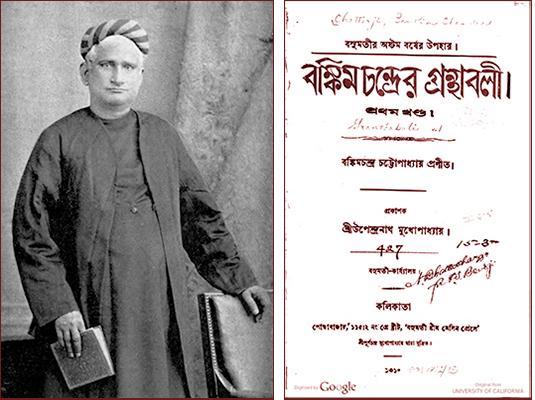

Bankimacandra Cattopadhyaya (1838-1894) was not only the very first novelist of the Bengali language but is also considered one of its greatest. He wrote the first novel in Bengali as well as the first novel in English by an Indian. His works are still avidly read and a poem in his historical novel Anandamatha titled “Vande Matram” (“Hail Mother”) so inspired Indian freedom fighters it was officially adopted as India’s national song (not the same as the national anthem which is a poem by Tagore).

Bankim was born in a Brahim family, and grew up in the town of Midnapur where his father worked for the colonial government. After his education Bankim followed his father into civil service while at the same time pursuing a successful literary career. Starting with poetry he turned towards writing novels. His first published novel, Rajmohan’s Wife, was composed in English. However, he soon turned to Bengali and in 1865 published the very first novel in the language called, Durgesanandini (“Daughter of the Lord of the Fort”). He continued to write novels as well as satirical and humorous sketches. A commentary he wrote on the Gita was published posthumously.

Outside Bengal, his historical novel Anandamatha (“The Monastery of Bliss”), published in 1882, became the most famous and somewhat controversial for its attitude towards Muslims. It is set during the Fakir Rebellion of the late 18th century when Bengalis rose up against the oppressive rule of the East India Company during a famine. As mentioned above, it contains an ode to the motherland conceived as a goddess titled “Vande Matram” that became very popular with Indian freedom fighters during the struggle for independence. Bankim’s political stances got him in trouble with British authorities in his own lifetime, but in 1894—the same year he died—Queen Victoria made him a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire.

Bankim belonged to a generation of Bengalis who had grown up under British rule and were able to reflect on the massive changes that rule had brought. The generation immediately before his had been the first to be exposed to western and modern ideas, and many of them accepted them with enthusiasm while others did so reluctantly. While Bankim did not question the adoption of western and modern ideas and technologies, he and members of his generation were more familiar with them and were in a position to critically judge the promises the British had made to Indians about the benefits of European rule and civilization. At the same time they had gained the confidence to appreciate aspects of their Indian and Hindu heritage which they wanted to hold onto as they modernized. Apart from their literary merits, these are some of the themes that make Bankim’s works relevant to this day.

Bengali, or Bangla to its nearly 230 million speakers, is an Indo-Aryan language belonging to the Indo-European family of languages. It is the official and predominant language of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, and also has many speakers in the neighboring Indian states of Tripura and Assam. With a rich and centuries old literary tradition it continues to be a major language of modern South Asia. At UC Berkeley, introductory and intermediate Bengali is taught through the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Granthabali

Title in English: Collected Works

Authors: Caṭṭopādhyāẏa, Baṅkimacandra, 1838-1894.

Imprint: Kalikata : Upendra Nath Mukhopadhyaya, Basu Mati Office, 1310-11 [1892/93-93/94].

Edition: 1st

Language: Bengali

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100787603

Other online editions:

- Bankim Rachanabali (volume 1 of complete works in Bengali), Internet Archive (Digital Library of India)

- The Abbey Of Bliss (English translation of Anandamath), Internet Archive (British Library)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Granthabali. Kalikata : Upendra Nath Mukhopadhyaya, Basu Mati Office, 1310-11 [1892/93-93/94].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

ucblib.link/languages

French

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Si c’est ici le meilleur des mondes possibles, que sont donc les autres?

If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others like?

— Voltaire, Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (trans. Burton Raffel)

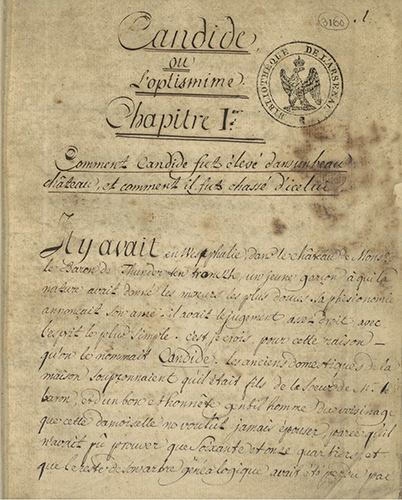

Voltaire, né François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), was a French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe more than any other thinker of his day. Born into a prosperous bourgeois Parisian family, his father steered him toward law, but he was intent on a literary career. His tragedy Oedipe, which premiered at the Comédie Française in 1718, brought him instant financial and social success. A libertine and a polemicist, he was also an outspoken advocate for religious tolerance, pluralism and freedom of speech, publishing more than 2,000 works in all possible genres during his lifetime. For his bluntness, he was locked up in the Bastille twice and exiled from Paris three times.[1] Fleeing royal censors, Voltaire fled to London in 1727 where he, despite arriving penniless, spent two and a half years hobnobbing with nobility as well as writers such as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.[2]

After his sojourn in Great Britain, he returned to the Continent and lived in numerous cities (Champagne, Versaille, Amsterdam, Potsdam, Berlin, etc.) before settling outside of Geneva in 1755 shortly after Louis XV banned him from Paris. “It was in his old age, during the 1760s and 1770s,” writes historian Robert Darnton, “that he wielded his second and most powerful weapon, moral passion.”[3] Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published the satirical novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme (“Candide, or Optimism”) featured in this entry. In 1762, he published Traité sur la tolerance (“Treatise on Tolerance”), which is considered one of the greatest defenses of religious freedom and human rights ever composed. Soon after its publication, the American and French Revolutions began dismantling the social world of aristocrats and kings that we now refer to as the Ancien Régime.[4]

With Candide in particular, Voltaire is credited with pioneering what is called the conte philosophique, or philosophical tale. Knowing it would scandalize, the story was published anonymously in Geneva, Paris and Amsterdam simultaneously and disguised as a French translation by a fictitious Mr. Le Docteur Ralph. The novella was immediately condemned for its blasphemy and subversion, yet within weeks sold 6,000 copies within Paris alone.[5] Royal censors were unable to keep up with the proliferation of illegal reprints, and it quickly became a bestseller throughout Europe.

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is considered one of its clearest precursors in both form and parody. Candide is the name of the naive hero who is tutored by the optimistic philosophy of Pangloss, who claims that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds” only to be expulsed in the first few pages from the opulent chateau in which he grew up. The story unfolds as Candide travels the world and encounters unimaginable human suffering and catastrophes. Voltaire’s satirical critique takes aim at religion, authority, and the prevailing philosophy of the time, Leibnizian optimism.

While the classical language of Candide is more than 260 years old, it is easy enough to comprehend today. As the lingua franca across the Continent, French was accessible to a vast French-reading public since gathering strength as a literary language since the 16th century.[6] However, no language stays the same forever and French is no exception. Old French, which is studied by medievalists at Berkeley, covers the period up to 1300. Middle French spans the 14th and 14th centuries and part of the early Renaissance when the study of French language was taken more seriously. Modern French emerged from one of the two major dialects known as langue d’oïl in the middle of the 17th century when efforts to standardize the language were taking shape. It was then that the Académie Française was established in 1635.[7] One of its members, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, published in 1647 the influential volume, Remarques sur la langue françoise, a series of commentaries on points of pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary and syntax.[8]

At UC Berkeley, scholars have been analyzing Candide and other French texts in the original since the university’s founding. The Department of French may have the largest concentration of French speakers on campus, and French remains like German, Spanish, and English one of the principal languages of scholarship in many disciplines. Demand for French publications is great from departments and programs such as African Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Comparative Literature, History, Linguistics, Middle Eastern Studies, Music, Near Eastern Studies, Philosophy, and Political Science. The French collection is also vital to interdisciplinary Designated Emphasis PhD programs in Critical Theory, Film & Media Studies, Folklore, Gender & Women’s Studies, Medieval Studies, and Renaissance & Early Modern Studies.

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is home to the most precious French holdings, including medieval manuscripts such as La chanson de geste de Garin le Loherain (13th c.) and dozens of incunables. More than 90 original first editions by Voltaire can be located in these special collections, including La Henriade (1728), Mémoires secrets pour servir à l’histoire de Perse (1745) Maupertuisiana (1753), L’enfant prodigue: comédie en vers dissillabes (1753) and a Dutch printing of Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (1759). Other noteworthy material from the 18th century overlapping with Voltaire include the Swiss Enlightenment and the French Revolutionary Pamphlet collections.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Davidson, Ian. Voltaire. New York: Pegasus Books, 2010. xviii

- Ibid.

- Darnton, Robert. “To Deal With Trump, Look to Voltaire,” New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018).

- Voltaire. Candide or Optimism. Translated by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Davidson, 291.

- Levi, Anthony. Guide to French Literature. Chicago: St. James Press, c1992-c1994.

- Kors, Alan Charles, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ibid.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Candide, ou L’optimisme (Manuscrit La Vallière)

Title in English: Candide, ou L’optimisme (La Vallière Manuscript)

Author: Voltaire, 1694-1778

Imprint: La Vallière (Louis-César, duc de). Ancien possesseur, 1758.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: French

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 3160)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b520001724

Other online editions:

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme , traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Paris: Lambert, 1759. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme. Première Partie 1. Édition revue, corrigée et augmentée par l’auteur. Aux Delices, 1763.(Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme, traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Seconde partie. Aux Delices, 1761. (Gallica)

- Candide ou L’optimisme. Préface de Francisque Sarcey; illustrations de Adrien Moreau. Paris: G. Boudet, 1893. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Illustré de trente-six compositions dessinées et gravées sur bois par Gérard Cochet. Paris: Les Editions G. Crès et Cie, 1921. (HathiTrust)

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated into English by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. (ebrary-UCB access only)

- Candide / Voltaire. [United States]: Tantor Audio: Made available through hoopla, 2006. ebook and audiobook (OverDrive-UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Candide, ou, l’Optimisme / traduit de l’allemand de Mr. le docteur Ralph. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Rey, MDCCLIX [1759].

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Édition présentée, établie et annotée par Frédéric Deloffre. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

- Candide. [Graphic novel] Interventions graphiques de Joann Sfar. Rosny: Éditions Bréal, 2003.

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated and edited by Theo Cuffe with an introduction by Michael Wood. New York : Penguin Books, 2005.

- Candide, ou L’optimiste. [Graphic novel] Scénario, Gorian Delpâture & Michel Dufranne; dessin, Vujadin Radovanovic; couleur, Christophe Araldi & Xavier Basset. Paris: Delcourt, 2013.

- Candide or, Optimism: The Robert M. Adams Translation, Backgrounds, Criticism. Edited by Nicholas Cronk. New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Turkish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

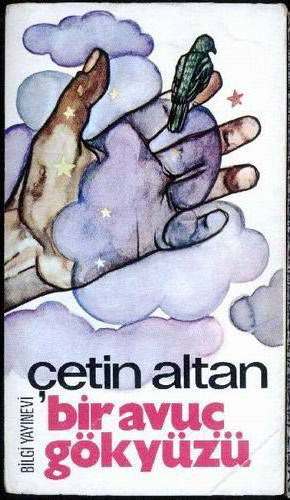

The Turkish writer Çetin Altan (1927-2015) was a politician, author, journalist, columnist, playwright, and poet. From 1965 to 1969, he was deputy for the left-wing Workers Party of Turkey—the first socialist party in the country to gain representation in the national parliament. He was sentenced to prison several times on charges of spreading communist propaganda through his articles. He wrote numerous columns, plays, works of fiction (including science fiction), political studies, historical studies, essays, satire, travel books, memoirs, anthologies, and biographical stories.[1]

His novel Bir Avuç Gökyüzü (A Handful of Sky), was published in 1974 and takes place in Istanbul. A 41-year-old politically indicted married man spends two years in prison and then is released. Several months later he is called into the police station where the deputy commissioner has him sign a notification from the public prosecutor’s office. This time, the man will serve three more years and he has a week to surrender to the courthouse. The novel chronicles the week of this man’s life before he serves his extended sentence. Suddenly, an old classmate with thick-rimmed glasses appears with the pretense to help. The classmate convinces the main character to petition his sentence and have it postponed for four months so that he can make the necessary arrangements to support his family. Unsurprisingly, the petition is rejected on the grounds of the severity of the purported offense that led to conviction. His classmate then urges the protagonist to take a freighter and flee the country, but instead he turns himself in. From the prison ward’s iron-barred windows he can only see a handful of sky.[2] The protagonist experiences lovemaking with his mistress mainly as a metaphor for freedom lost; the awkward and clumsy sex he has with his wife, on the other hand, seems an apt metaphor for the emotionally inert life he leads both in and outside of prison.[3]

Çetin Altan was well aware of language’s power and wrote articles on the Turkish language in the newspapers where he was employed as a journalist. At the age of 82 and during his acceptance speech at the Presidential Culture and Arts Grand Awards in 2009, Mr. Altan said, “İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanını sever’’ (A person loves the homeland as much as he loves the flavor of his own language). He loved Turkish and wrote with that love. In his works, as he put it, he “never betrayed the language and the writing.”[4]

An argument can easily be made to study Turkish. There are 80 million people who speak Turkish as their first language, making it one of the world’s 15 most widely spoken first languages. Another 15 million people speak Turkish as a second language. For example there are over 116,000 Turkish speakers in the United States, and Turkish is the second most widely spoken language in Germany. Studying Turkish also lays a solid foundation for learning other modern Turkic languages, like Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Uzbek, and Uighur. The different Turkic languages are closely related and some of them are even mutually intelligible. Many of these languages are spoken in regions of vital strategic importance, like the Caucasus, the Balkans, China, and the former Soviet Union. Mastery of Turkish grammar makes learning other Turkic languages exponentially easier.[5]

Turkish is not related to other major European or Middle Eastern languages but rather distantly related to Finnish and Hungarian. Turkish is an agglutinative language, which means suffixes can be added to a root-word so that a single word can convey what a complete sentence does in English. For example, the English sentence “We are not coming” is a single word in Turkish: “come” is the root word, and elements meaning “not,” “-ing,” “we,” and “are” are all suffixed to it: gelmiyoruz. The regularity and predictability in Turkish of how these suffixes are added make agglutination much easier to internalize.[5] [6] At UC Berkeley, modern Turkish language courses are offered through Department of Near Eastern Studies.[7]

When I was asked to write a short essay about the Turkish language based on a book, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the UC Berkeley Library has many of Çetin Altan’s books in their original language. While he was my favorite author when I was in high school and in college in Turkey during the 1970s and 1980s, my move to the United States and life in general caused these memories to fade away. Now I am excited and feel privileged with the prospect of reading his books in Turkish again and rediscovering them after all these years.

Contribution by Neil Gali

Administrative Associate, Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Sources consulted:

- http://www.turkishculture.org/whoiswho/memorial/cetin-altan-953.htm (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://www.evvelcevap.com/bir-avuc-gokyuzu-kitap-ozeti (accessed 3/10/20)

- “İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanı sever,” (October 21, 2017) P24: Ağimsiz Gazetecilik Platformu = Platform for Independent Journalism. http://platform24.org/p24blog/yazi/2492/-insan-kendi-dilinin-lezzetini-sevdigi-kadar-vatani-sever (accessed 3/10/20)

- İrvin Cemil Schick, “Representation of Gender and Sexuality in Ottoman and Turkish Erotic Literature,” The Turkish Studies Association Journal, Vol. 28, No. 1/2 (2004), pp. 81-103, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43383697 (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://names.mongabay.com/languages/Turkish.html (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://www.bu.edu/wll/home/why-study-turkish (accessed 3/10/20)

- http://guide.berkeley.edu/courses/turkish (accessed 3/10/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Bir Avuç Gökyüzü

Title in English: A Handful of Heaven

Author: Altan, Çetin, 1927-2015

Imprint: Kavaklıdere, Ankara : Bilgi Yayınevi, 1974.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Turkish

Language Family: Turkish, Turkic

Recommended Online Resource:

“İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanı sever,” (October 21, 2017) P24: Ağimsiz Gazetecilik Platformu = Platform for Independent Journalism. Blog post of tribute to the writer with photos, videos, etc.

http://platform24.org/p24blog/yazi/2492/-insan-kendi-dilinin-lezzetini-sevdigi-kadar-vatani-sever (accessed 3/10/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Breton

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“Lec’h ma vije ‘r zorserienn hag ar zorserezed;

Hag a diskas d’in ‘r secret ewit gwalla ann ed.”

“Where were the wizards and witches,

for they are are the ones who taught me how to spoil the wheat.”

from “Janedik ar zorseres” in Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne

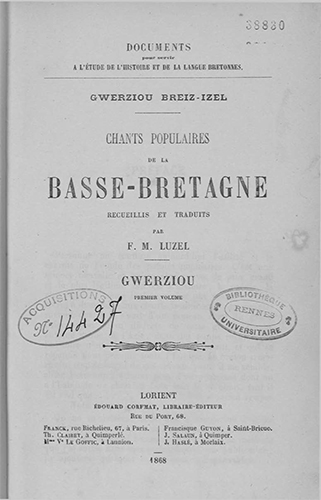

François-Marie Luzel (1821-1895) was a French folklorist and Breton-language poet who assumed a rigorous approach to documenting the Breton oral tradition. After publishing a book which included some of his own poetry in 1865 entitled Bepred Breizad (Always Breton), he published a selection of the texts that he collected in the two-volume set Chants et chansons populaires de la Basse-Bretagne (Melodies and Songs from Low-Brittany) in 1868. It is this latter work that is featured here and offers a parallel translation in French with the intent of making the corpus of songs available to as wide a readership as possible. Throughout the 19th century, Celtic revivalists such as the controversial Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué undertook an equally ambitious project to collect, preserve, and disseminate folk songs and stories. According to Stephen May, “The modern Breton nationalist movement draws heavily on the persistence of Breton traditions, myths memories and symbols (including language) which have survived in various forms, throughout the period of French domination since 1532.”[1]

Of the many minority languages spoken in France today, Breton (Brezhoneg) is the only one of the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family. Its history can be traced to the Brythonic or Brittonic language community that once extended from Great Britain to Armorica (present-day Brittany) and as far as northwestern Spain beginning in the 9th century. It was the language of the upper classes until the 12th century, after which it became the language of commoners in Lower Brittany as the nobility adopted French. Because of the predilection for French and Latin in the early modern and modern periods, there exists a limited tradition of Breton literature. After the revolution of 1789 when French became the official language, regional languages and dialects became viewed as anti-democratic and hence prohibited in commercial and workplace communications. The Loi Deixonne of 1951 opened the doors grudgingly for the teaching of Breton in France together with Basque, Catalan and Occitan. There has since been some expansion to roughly 5% of the school population.[2] Despite a flowering of literary production since the 1940s, Breton has been classified as “severely endangered” with approximately 250,000 native speakers.[3] Since 1911, Breton has been a core language taught in UC Berkeley’s Celtic Studies program, the oldest of its kind in the country.[4]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- May, Stephen. Language and Minority Rights: Ethnicity, Nationalism and the Politics of Language. 2nd New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998.

- UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas.

- History of Celtic Studies at UC Berkeley, http://celtic.berkeley.edu/celtic-studies-at-berkeley

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne, recueillis et traduits par F.M. Luzel

Title in English: Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Melodies and Songs from Low-Brittany

Author: Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895.

Imprint: Lorient, É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.] 1868-74.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Breton

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: Université de Rennes 2

URL: http://bibnum.univ-rennes2.fr/items/show/321

Other online editions:

- HathiTrust Digital Library: Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895. Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne. vols. 1-2. Lorient: É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.], 1868-74.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895. Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne. vols. 1-2. Lorient: É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.], 1868-74.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Thai

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

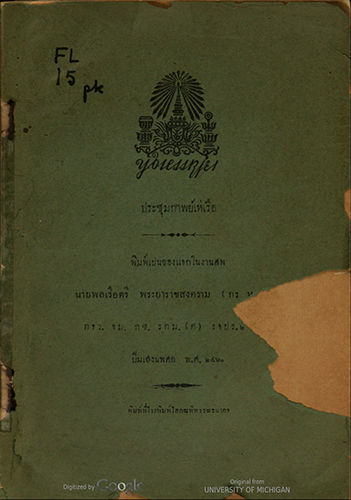

From the beginning of its known history, Thai was the official language of the monarchy of Thailand. Spoken by more than 60 million people today, it retains a formal vocabulary of respect, used in ritual and in addressing the royal family. Its writing system is a careful adaptation of that of Khmer to a language with a distinct sound pattern and flavor.[1]

Prachum kāp hē r̄ưa is a collection of Kāp hē r̄ưa. Kāp hē r̄ưa is a traditional genre of Thai literature written and used for royal barge processions in Thailand. The content of Kāp hē r̄ưa is usually a description of a variety of royal barges and natural scenery that the poet sees along the way, especially trees, fish, and birds. Some poets also write about their lovers from whom they have to part upon their journey.

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers programs in both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia.[2] Outside of SSEAS where beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Thai, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Anthropology, Asian American Studies, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Folklore, History, Linguistics and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and culture of Thailand.[3]

Arthit Jiamrattanyoo

PhD Student, Department of History, University of Washington

Sources consulted:

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 2/21/20)

- Thai (THAI) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 2/21/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Prachum kāp hē r̄ưa

Title in English: n/a

Author: Gedney, William J., Damrongrāchānuphāp Prince, son of Mongkut, King of Siam 1862-1943.

Imprint: [Phranakhō̜n?]: Rōngphom Sōphon Phiphatthanākō̜n, 2460 [1917].

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Thai

Language Family: Kra-Dai

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000415896

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Polish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

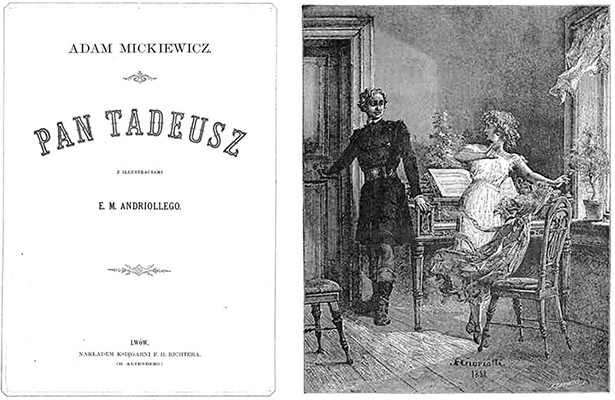

Modern day academics and literary scholars have spent considerable time studying the phenomenon related to the use of literature to create national heroes. While, the use of literary forms gives a particular author the means to incorporate the cultural sensitivities, the literary forms that evolve are functions of the society and time in which a particular author was born. Pan Tadeusz as an epic poem is not an exception but reinforces the stereotypes of a particular period through the poetics of Adam Mickiewicz.

Adam Mickiewicz was born in Nowogródek of the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania in 1798. Nowogródek is today known as Novogrudok and is located in Republic of Belarus. He was educated in Vilnius, the capital of today’s Lithuania. He is recognized as the national literary hero of Poland and Lithuania. However, most of his adulthood was spent in exile after 1829. In Russia, he traveled extensively and was a part of St. Peterburg’s literary circles.[1] There have been several works that track the trajectory of Mickiewicz’s travel and exile. Pan Tadeusz reflects the realities of the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth from the perspective of the poet. The drive for liberty and freedom were indeed two traits of Adam Mickiewicz’s life journey that cannot be ignored. The synopsis of the story has been summarized below. Also of interest are the illustrations to accompany the storyline. One prominent illustrator was his compatriot Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836-1893).[2]

Pan Tadeusz is the last major work written by Adam Mickiewicz, and the most known and perhaps most significant piece by Poland’s great Romantic poet, writer, philosopher and visionary. The epic poem’s full title in English is Sir Thaddeus, or the Last Lithuanian Foray: a Nobleman’s Tale from the Years of 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books of Verse (Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem). Published in Paris in June 1834, Pan Tadeusz is widely considered the last great epic poem in European literature.

Drawing on traditions of the epic poem, historical novel, poetic novel and descriptive poem, Mickiewicz created a national epic that is singular in world literature.[3] Using means ranging from lyricism to pathos, irony and realism, the author re-created the world of Lithuanian gentry on the eve of the arrival of Napoleonic armies. The colorful Sarmatians depicted in the epic, often in conflict and conspiring against each other, are united by patriotic bonds reborn in shared hope for Poland’s future and the rapid restitution of its independence after decades of occupation.

One of the main characters is the mysterious Friar Robak, a Napoleonic emissary with a past, as it turns out, as a hotheaded nobleman. In his monk’s guise, Friar Robak seeks to make amends for sins committed as a youth by serving his nation. The end of Pan Tadeusz is joyous and hopeful, an optimism that Mickiewicz knew was not confirmed by historical events but which he designed in order to “uplift hearts” in expectation of a brighter future.

The story takes place over five days in 1811 and one day in 1812. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had already been divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria after three traumatic partitions between 1772 and 1795, which had erased Poland from the political map of Europe. A satellite within the Prussian partition, the Duchy of Warsaw, had been established by Napoleon in 1807, before the story of Pan Tadeusz begins. It would remain in existence until the Congress of Vienna in 1815, organized between Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia and his defeat at Waterloo.

The epic takes place within the Russian partition, in the village of Soplicowo and the country estate of the Soplica clan. Pan Tadeusz recounts the story of two feuding noble families and the love between the title character, Tadeusz Soplica, and Zosia, a member of the other family. A subplot involves a spontaneous revolt of local inhabitants against the Russian garrison. Mickiewicz published his poem as an exile in Paris, free of Russian censorship, and writes openly about the occupation.

The poem begins with the words “O Lithuania”, indicating for contemporary readers that the Polish national epic was written before 19th century concepts of nationality had been geopoliticized. Lithuania, as used by Mickiewicz, refers to the geographical region that was his home, which had a broader extent than today’s Lithuania while referring to historical Lithuania. Mickiewicz was raised in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the multicultural state encompassing most of what are now Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. Thus Lithuanians regard the author as of Lithuanian origin, and Belarusians claim Mickiewicz as he was born in what is Belarus today, while his work, including Pan Tadeusz, was written in Polish.”

Polish is a prominent member of the West Slavic language group. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles who live in various parts of world including the United States. Poles have been involved in the history of the American Revolution from early on. One such example is that of Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko who was an engineer and fought on the side of American revolution.

At UC Berkeley, Polish language teaching has been a major part of the portfolio of the Slavic languages that are being taught at the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. This department was home to UC Berkeley’s only faculty member, Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004), to have ever received the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature.[4] The tradition of Milosz is continued today in the same department by Professor David Frick. Professor John Connelly in the History department is another luminary scholar of Polish history.

Marie Felde, who reported on his death in the UC Berkeley News Press release on 14th August 2004 noted, “When Milosz received the Nobel Prize, he had been teaching in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature at Berkeley for 20 years. Although he had retired as a professor in 1978, at the age of 67, he continued to teach and on the day of the Nobel announcement he cut short the celebration to attend to his undergraduate course on Dostoevsky.”[5]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Adam Mickiewicz, 1798-1855; In Commemoration of the Centenary of His Death in UNESDOC DIGITAL LIBRARY (accessed 2/21/20)

- Andriolli : Ilustracje do “Pana Tadeusza” (accessed 2/21/20)

- “Pan Tadeusz – Adam Mickiewicz,” Culture.pl (accessed 2/21/20)

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1980, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1980/summary (accessed 2/21/20)

- UC Berkeley News (August 14, 2004), https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/08/15_milosz.shtml (accessed 2/21/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Pan Tadeusz

Title in English: Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania

Author: Mickiewicz, Adam, 1798-1855.

Imprint: Lwów : Nakładem Księgarni F.H. Richtera (H. Altenberg) , [1882?].

Edition: unknown

Language: Polish

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112046983406

Other online editions:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Gallica – Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Project Gutenberg)

- Pan Tadeusz czyli ostatni zajazd na Latwie. Warszawa : Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska, 2016.

- Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books. Translated into English by George Rapall Noyes. London : Dent ; New York : Dutton, 1917. (Project Gutenberg )

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edition. Paryz, 1834.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)