Tag: “The Languages of Berkeley”

Coptic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Coptic Christians constitute the largest indigenous Christian community in the Middle East, concentrated primarily in Egypt, but more recently extending to growing diaspora communities in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. The vast majority of Coptic Christians are members of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, one of the six Oriental Orthodox churches that was outcast by other Christian churches as a result of theo-political disputes during and following the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. The Coptic language has been a source of communal belonging for Egyptian Orthodox Christian communities, and of special concern to Orientalists of the modern period interested in the ancient languages of the Middle East.

Fundamentally, Coptic is the last written phase in the evolution of the language of the ancient Egyptians. The Coptic language may therefore be defined as the late Egyptian vernacular inscribed in the Greek alphabet, to which are juxtaposed multiple additional characters from demotic that number seven in the current surviving dialect, Bohairic. The rapid spread of Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries CE influenced how and in what form Coptic was transmitted. Christians, in their missionary approach, revived the use of the local vernacular dialects. They primarily served as vehicles for transmitting Scripture. There are six major dialects of Coptic: Sahidic, Bohairic, Fayyumic, Akhmimic, Lycopolitan, Mesokemic, with multiple subdialects or minor ones.[1]

Early on, the language was primarily a translation tool for Christian literature originally written in Greek, such as the Scriptures; as well as a mechanism to mask the heterodox literature of Gnostic and Manichean communities from the eyes of agents of the Orthodox authorities in Alexandria. Following the Great Persecutions of the early fourth century, known as the “Era of the Martyrs,” two large-scale changes took place: the accelerated Christian conversion of the Egyptian countryside and the rapid growth of monasticism. These changes helped to elevate and expand the role of Coptic from a mode of translation to a complete literary language.[2] Following the Arab Conquest of Egypt, Arabic slowly took precedence as a language of government and administration, and became the lingua franca of literary composition among the elite Copts of the time a few centuries later. Consequently, Coptic literature became restricted to hagiographic and liturgical compositions. Even hagiographic works were adapted for liturgical use.

Coptic persisted as a spoken and liturgical language until approximately the 13th century which was marked by the emergence of native scholars who composed Coptic grammars in Arabic as well as Arabic-Coptic dictionaries to help preserve the language. Among these were Aulad al-‘Assal and Abu al-Barakat ibn Kabar who flourished under the rule of the Fatimid and Ayyubid dynasties of Egypt.[3] Nevertheless, Coptic steadily declined, but European travelers to Egypt of the 17th and 18th centuries would briefly note the continuance of the language among Copts in Upper Egypt.[4] [5] Preeminent Coptologist Hany Takla (2014) of the Saint Shenouda the Archimandrite Coptic Society has called the period between the 15th and 18th centuries the “dormant stage,” whereby the use of Coptic was at an all-time low. Through Orientalist and colonial influence, as well as Coptic initiative, a revival took place in the mid-19th century where the essence of reform was to “modernize” the Coptic language through its standardization. Historian Paul Sedra has argued that educated Copts initiated processes of textualizing Coptic heritage, and advocated for reform’s civilizing and disciplinary capacity.[6]

During fieldwork between 2014-2015 at the Coptic Cathedral in Cairo, I sat in on a number of Coptic language courses. One of the central drivers of Coptic language retention like these courses has been the institutional authority of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Church sponsorship has been vital in reintroducing Coptic classes in order to familiarize Coptic youth with liturgical terminology as well as cultivate a living heritage among contemporary Egyptian Orthodox Christians. Anthropologist Carolyn Ramzy has examined the continued importance of Coptic language to identity in 20th and 21st century Egypt and within its contemporary diasporas through the lens of church hymnody known as alḥān. Before the Sunday School movement of the early 20th century, Coptic Orthodox worship was largely limited to Church services, where parishioners traditionally practiced all of their official church rites accompanied by alḥān. As alḥān texts are in Coptic, few people—clerics, and educated cantors and laymen—sung and understood the genre. (Although, Coptic literacy in general declined at a faster rate in Lower Egypt than in Upper Egypt.) In the push for reform, though, parishioners increasingly joined Orthodox liturgical services in song, along with educated cantors and clergy. With the rise of digital archives, alḥān have become more widely sung and broadly understood by deacons and choirs, as well as laity in Egypt and in diaspora.[7] The Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt has emphasized the importance of alḥān as an integral part of Coptic heritage and a means to claim indigeneity—to distance Copts from Western missionary and contemporary political efforts at structural and cultural transformation.[8]

As diaspora communities have grown, discussions of the necessity of Coptic language to the Alexandrian Rite of Orthodox Christianity—in its hymns and liturgical practice—have been ongoing, as the Coptic Orthodox Church expands and seeks to evangelize outside of Egypt’s national boundaries.[9] For all intents and purposes, the Coptic language is a “dead” language—one not in vernacular use today. Instead, the Coptic language is kept alive through liturgical practice and the academic field of Coptology. Language preservation in the Coptic community has historically been about community preservation. During my own dissertation research between Egypt and the United States, Copts described extinction of the Coptic vernacular as a “failure of the community.” For those in the diaspora, studying Coptic, whether at a theological seminary or through local parishes, has forged a new kind of ethos—leaving behind the physical place of Egypt as a space of belonging.

The retention of Coptic in the United States has taken on the language of survival. At the 2014 North American Mission and Evangelism Conference (N.A.M.E.) in Florida, one diaspora priest described the importance of language to communal belonging in Egypt in this way: “We were fighting for our survival. The Church became a haven for the culture, spirituality, etc. Once the Ottoman empire weakened and the missionaries came to Egypt, the Coptic Church created a defense mechanism that has been carried over with our immigration leading to…an island. The belief that we have to teach people the language and culture in order to survive….”[10] Many in the Coptic diaspora have contended with the continued liturgical use of the Coptic language, debating whether it is the role of the Church to hold the remaining remnants of Coptic language’s persistence among this transnational community. Yet, the language’s significance continues to be pregnant with meaning.

As poet Matthew Shenoda writes:

“Time a question

only the Nile can answer

meandering through papyrus fields & baqara expanse

her sediment the testament of Coptic”[11]

The Coptic language, while now secluded to liturgical and academic circles, still maintains communal importance in Egypt and in diaspora as a mode of perseverance and sedimented belonging.

Contribution by Candace Lukasik

PhD, Department of Anthropology

Postdoctoral Fellow, Washington University in St. Louis

Sources consulted:

- Rodolphe Kasser. “Language(s), Coptic.” In Coptic Encyclopedia, 8 vols. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya. New York: Macmillan, 1991.

- Hany Takla. “The Coptic Language: The Link to the Ancient Egyptians.” In The Coptic Christian Heritage: History, Faith, and Culture. Edited by Lois M. Farag. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Samuel Moawad. “Coptic Arabic Literature: When Arabic Became the Language of Saints.” In The Coptic Christian Heritage: History, Faith, and Culture. Edited by Lois M. Farag. London: Routledge, 2014.

- H. Worrell. A Short Account of the Copts. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press: Oxford University Press, 1945.

- Aziz S. Atiya. History of Eastern Christianity. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968.

- Paul Sedra. From Mission to Modernity: Evangelicals, Reformers, and Education in Nineteenth Century Egypt. London: Bloomsbury, 2011.

- Carolyn Ramzy. “Autotuned Belonging: Coptic Popular Song and the Politics of Neo-Pentecostal Pedagogies.” Ethnomusicology 60(3), 2016.

- Heather Sharkey. American Evangelicals in Egypt: Missionary Encounters in an Age of Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Nicholas Ragheb. “Coptic Ethnoracial Identity and Liturgical Language Use.” In Contemporary Christian Culture: Messages, Missions, and Dilemmas. Edited by Omotayo O. Banjo and Kesha Morant Williams. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018.

- Michael Sorial. Incarnational Exodus: A Vision for the Coptic Orthodox Church in North America. Washington D.C.: St. Cyril of Alexandria Society Press, 2014.

- Matthew Shenoda. Somewhere Else. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2005.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

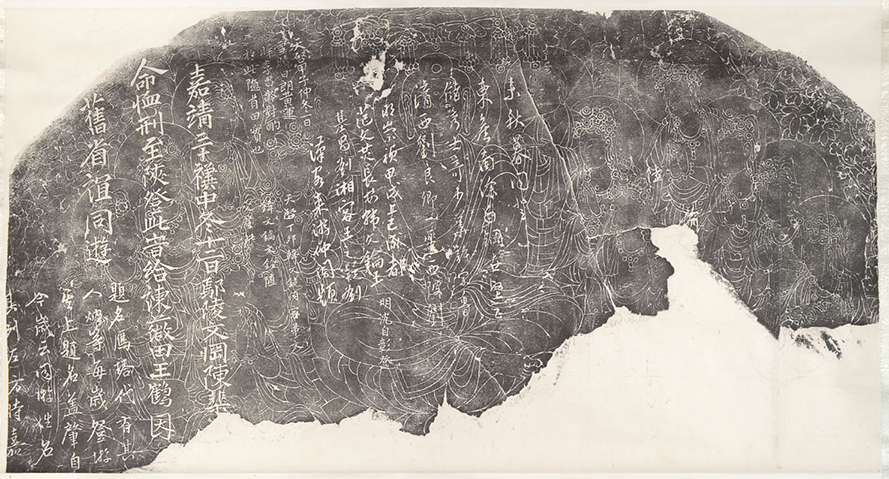

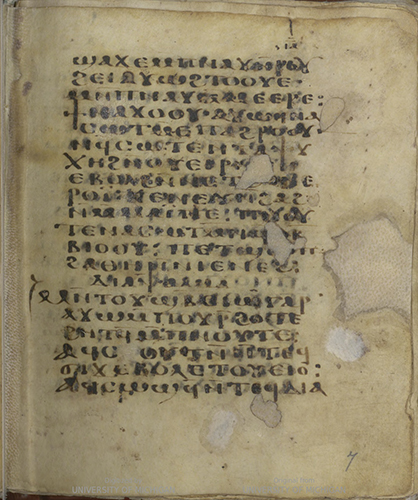

Title: Psalter manuscript

Author: unknown

Imprint: 6th century

Edition: n/a

Language: Coptic

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Egyptian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101703234

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Russian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

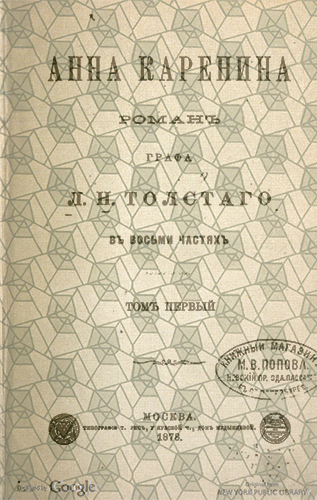

Leo Tolstoy’s literary work Anna Karenina first appeared as a series in the Russian journal Russkii Vestnik from 1873 through 1877.[1] It was published in Moscow in its book form in 1878. Considered the supreme masterpiece of realist fiction, Vladimir Nabokov called Anna Karenina “one of the greatest love stories in world literature.” Matthew Arnold claimed it was not so much a work of art as “a piece of life.” Set in imperial Russia, Anna Karenina is a vibrant and complex meditation on passionate love and disastrous infidelity. It is also a work of exquisite patterning, draped around the stories of two protagonists who meet only once in the course of the text. The first English edition was published in 1886 in New York by Thomas J. Crowell & Co and translated by Nathan Haskell Dole.

The Slavic collections at the UC Berkeley Library represent a significant treasure trove of material, the product of a century and a half of devoted, attentive collecting. The Library’s Slavic collection is easily the strongest on the West coast, and, indeed, Berkeley probably takes a back seat in this area only to Harvard’s Widener Library and the Library of Congress.

Russian has been taught at Berkeley since 1901, and The Slavic Department has been in existence for over a century. Berkeley was the location of the founding of the first chapter of Dobro Slovo, a national honor society for students of Slavic Languages. The Department has been fortunate to be the home of many exceptional scholars, including Czeslaw Milosz, the University’s only Nobel Prize winning professor in the Humanities. In the most recent report commissioned by the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) to assess the state of research and graduate training in U.S.-based academic institutions, Berkeley’s graduate program was ranked as the top program in the country, followed by Harvard, Columbia and Princeton.

The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at UC Berkeley has several scholars whose specialization is 19th-century Russian literature including Professors Eric Naiman and Irina Paperno. Professor Paperno’s book on Tolstoy Who, What am I?” Tolstoy Struggles to Narrate the Self has been instrumental in providing insight into the world of Tolstoy.[2] Professor Harsha Ram has further provided a glimpse of interactions between Russia’s both European and Asian roots in his essay on prisoners of the Caucasus in the anthology Tolstoy’s Short Fiction: Revised Translations, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism edited and with revised translations by Michael R. Katz.[3]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Eric Naiman, Professor

Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures

Sources consulted:

- Russkīĭ vi︠e︡stnik. Moskva: V. tip. T. Volkova. (HathiTrust Digital Library) Print edition held in Main Stacks/NRLF.

- Paperno, Irina. Who, What am I?” Tolstoy Struggles to Narrate the Self. Ithaka, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014.

- Tolstoy’s Short Fiction: Revised Translations, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism. Edited and translated from the Russian by Michael R. Katz. New York: Norton & Co., c2008.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Anna Karenina

Title in English: Anna Karenina

Author: Tolstoy, Aleksey Konstantinovich, graf, 1817-1875.

Imprint: Moskva: Tip. T. Ris, 1878.

Edition: 1st

Language: Russian

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (New York Public Library)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008614462

Other online editions and resources:

- Anna Karenina / L.N. Tolstoĭ; pod redakt︠s︡īeĭ i s primi︠e︡chanīi︠a︡mi P.I. Biri︠u︡kova; s ris. M. Shcheglova, A. Moravova i A. Korina. Moskva : Izd. T-va I.D. Sytina, 1914.

- Anna Karénina: In Eight Parts by Count Lyof N. Tolstoï, Translated by Nathan Haskell Dole. New York: T.Y. Crowell & Co., ©1914.

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy; introduction and notes by E.B. Green. Hertfordshire [England]: Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 2011.

- An article about the new translations of Anna Karenina was published in the NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/28/books/review/new-translations-of-tolstoys-anna-karenina.html (accessed 7/9/20)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Anna Karenina / L.N. Tolstoĭ; pod red. i s primi︠e︡chanii︠a︡mi P.I. Biri︠u︡kova; s ris. M. Shcheglova, A. Moravova i A. Korina. Moskva: Izd. T-va I.D. Sytina, 1914.

- Anna Karenina: Backgrounds and Sources Criticism / Leo Tolstoy; the Maude translation revised by George Gibian; edited by George Gibian. New York: Norton, c1995.

- Many other English translations are also available through OskiCat.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Ancient Korean

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

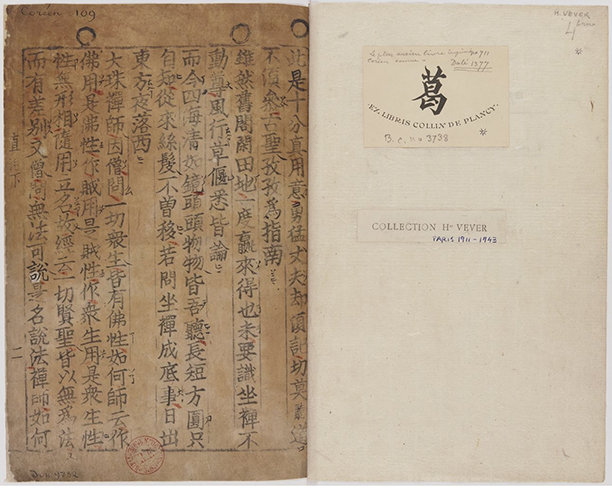

Written by the Buddhist monk Kyŏnghan Kyŏnghan and printed in Hŭngdŏksa Temple in 1377 in Korea this work of Zen Buddhism is referred to as Chikchi. The collection is abstracted from preachment, conversations and letters by many monks. The main idea of Chikchi is that genuine attainment of Nirvana is completed when people realize the nature of the conscientious mind in human equals to the nature of Buddha. As compiler, Kyŏnghan added other core contents to the original copy sent by the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) in China, and it was used as a textbook, primarily for the education of Sŏn (Zen) monks and not published in large quantities.[1]

During the Koryŏ dynasty (918-1392) in Korea, Buddhism was so popular that Koryŏ was often referred to as a Buddhist state. Although Confucianism was the political creed of the Koryŏ state, Buddhism served as its spiritual guidance and had a significant impact on the daily life of the Koryŏ people.The reason this edition of the book became so famous is that because it is the first in the world to be printed with movable metal type. It predates by nearly 75 years Johannes Gutenberg’s acclaimed 42-line Bible printed in Germany between 1452-1455. UNESCO confirmed the book as the world’s oldest metalloid type and registered it as part of the “Memory of the World” in September 2001.[2]

During the time of the Korean Empire (1897-1910), the book was removed from Seoul by the French diplomat and Victor Collin de Plancy. It was one of the numerous books that he acquired and kept in his private library, and which he in turn handed over to Henry Vever, a preeminent jeweler and collector of Asian antiques. Chikchiwas in turn donated to the National Library of France (Bibliothèque nationale de France) in 1950.[3] Only the second volume of the book has survived to the present-day, and just 38 of its 89 chapters have been preserved.

As the official language of both South and North Korea, Korean is the native language of more than 77 million people worldwide.[4] The Library’s Korean holdings exceed 102,000 volumes. Outstanding among these are the 4,000+ volumes of the Asami library, assembled by Asami Rintarō in the early decades of the 20th century and purchased by the Library 30 years later.[5] In 1942, UC Berkeley became the first university in the country to offer instruction in Korean, which continues to be taught for all academic levels in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures.

Contribution by Jaeyong Chang

Librarian for the Korean Collections, C.V. Starr East Asian Library

Sources consulted:

- Kim, Jongmyung. “The Chikchi and Its Positions in Fourteenth-Century Korea,” Religions 2020, 11(3), 126; https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030126

- Garry, Jane, and Carl R. G. Rubino. Facts About the World’s Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World’s Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H.W. Wilson, 2001.

- Kyŏnghan, 1299-1375. Chikchi. Chʻungbuk Chʻŏngju-si : Chʻŏngju Ko Inswae Pangmulgwan, 2005.

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (accessed 6/18/20)

- UC Berkeley Center for Korean Studies (accessed 6/18/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: 白雲和尙抄錄佛祖直指心體要節 (Paegun Hwasang chʻorok Pulcho chikchi simchʻe yojŏl) vol. 2

Title in English: Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests

Author: Kyŏnghan, 1299-1375

Imprint: Hŭngdŏksa, Ch’ŏngju, Korea (1377).

Edition: 1st

Language: Korean, or Traditional Chinese (so-called “Hanmun” in Korean)

Language Family: Koreanic

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10527116j

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Chikchi. ha / [pʻyŏnja Kyŏnghan]・直指・ 下/[編者景閑. Sŏul: Taehan Minʼguk Munhwa Kongbobu Munhwajae Kwalliguk, 1987. Facsimile of 1377 edition in case.

- Chikchi. ha / [pʻyŏnja Kyŏnghan]. 直指. 下 / [編者 景閑]. Seoul: Taehan Minʼguk Munhwa Kongbobu Munhwajae Kwalliguk, 1973. Vol. 1: Reprint. Original text of 1377 printing. Vol. 2: Pulcho chikchi simchʻe yojŏl haeje / Chʻŏn Hye-bong in English, French, Japanese and Korean.

- Pulcho chikchi simchʻe yojŏl / Paegun Sŏnsa chiŭm; Pak Mun-yŏl omgim. 불조직지심체요절 / 白雲禪師지음 ; 박문열옮김. Sŏul-si: Pŏmusa , 1997.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Finnish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, is a collection of folklore stories, much in the spirit of the German Nibelungenlied or Old English Beowulf. The Kalevala starts with the origins of the earth, its first people, spirits and animals, and ends with the departure of the main protagonist and the arrival of a “golden child”, a new era.

The Kalevala is based on poetry called runos or runes, collected and compiled by Elias Lönnrot, a countryside doctor who had a keen interest in linguistics and, especially, in oral folklore. He set out for his first of many oral folklore collection journeys in the early 1830s and journeyed to the Karelian Isthmus, to areas that were then and are also nowadays part of Russia. The areas he visited were populated by Finnish speakers and considered as part of Finland by many. Lönnrot’s method of collection was simple: he listened to local singers and wrote down what he heard. In the process of compiling the transcripts, he surely took liberties to compose parts himself as well.

When Lönnrot started the Kalevala project there was no sovereign nation called Finland. Before becoming independent in 1917, the area we know now as Finland was under either Swedish or Russian rule for centuries. In Lönnrot’s times, Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia. National romantic ideas of one national hailing from shared, mystical origins were no inventions of Lönnrot’s—quite the contrary. Winds of changes were blowing across Europe as Lönnrot walked along the Russian Isthmus collecting folklore. Europe was a turmoil of revolutions.

Many artists and thinkers in the Grand Duchy of Finland were excited about the Finnish language, culture, and the budding ideas of an independent nation. A national epic seemed needed, almost necessary, and in many ways it was perhaps perceived as proof for the right of the Finnish people to their own sovereign country, language and identity. Lönnrot was a Swedish speaker who saw the need and importance of a shared language for an emerging nation that was not Swedish or Russian, the languages of an oppressor, but Finnish, the language of the people who lived in the Grand Duchy.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835 and a second, reworked edition came out in 1849. The 1849 edition is the version that is still read today. It has 22,795 verses that are divided into several dozen stories. Together these stories create a whole, grand narrative. In the center of the runes are two tribes, the people of Kaleva led by the old, steadfast Väinämöinen, a powerful spiritual leader with the gift of song. In Pohjola, the North, rules a mighty old woman, Louhi, a witch, the ragged toothed hag of the North. Both tribes have fortunes and misfortunes in the stories: they venture out to compete for the hand of beautiful and clever maidens, they fight, they love, they die horrible deaths in the jaws of monsters or at the hands of their foes—just like the fate of heroes in all epic stories. What makes the Kalevala different from other epic stories is the vulnerability of its heroes. Where mighty godlike heroes of other epic stories escape from the flames of dragons and the horrors of cave dwelling creatures, the characters of the Kalevala suffer defeats, cry in pain and loneliness, never win the heart of the person they court, break bonds that were never to be broken and, in the end, there is death, the ultimate departure. The characters have a human tenderness that is rarely found in epic stories with heroes and villains.

Song is central in the Kalevala. We can read lengthy passages about spells Väinämöinen sings when he builds a boat to carry him across the stormy seas to Pohjola, how spells can be used to enchant someone, or which spell to sing in order to retrieve a missing spell from the belly of a forest spirit. Kalevala is full of singing competitions, exchanges of spells between characters—the song is mightier than the sword. The Kalevala is written in a strict tetrameter and is meant to be sung rather than read. An identifiable character of the Kalevala is the use of alliteration: two or more words in a line begin with the same sound. In strong alliteration even the following vowel is the same. Here, an example from the very first lines of the Kalevala:

Mieleni minun tekevi = mastered by desire impulsive

aivoni ajattelevi = by a mighty inward urging

Lähteäni laulamahan = I am ready now for singing

saa’ani sanelemahan = ready to begin the chanting

Poetry as a genre poses challenges to the translator, and the Kalevala’s form makes translation that captures the meter impossible. Despite the intricate nature of the Kalevala, the epic has been translated into numerous languages, including English.

Many artists found inspiration in the Kalevala. For example, Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1861-1935), a Finnish contemporary of Edward Munch (1863-1944), painted large Kalevala themed frescoes for the Finnish pavilion in the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris. In designing and decorating this entire pavilion dedicated to Finland (a country that did not yet exist), the Finnish cultural elite demonstrated its national spirit. Kalevala themes were central inspirations also for the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957).

But is the Kalevala Finnish? Is it a compilation of authentic Finnish oral poetry, or did Lönnrot in fact appropriate oral tradition he collected on his journeys and simply called it Finnish? The popular use of the book had a great influence on the formation of a positive Finnish identity, and to this day the Kalevala holds a firm position in Finnish culture. Discussing the Kalevala’s origins in the context of collecting oral traditions reveals its historical burden. This is the case for many epic stories and old poetry; the Old Norse and Old Saxon poetic forms can be scrutinized in the same light. Whose poems are these? Who claimed ownership and to what end? The Kalevala can be used as reading material for the pure enjoyment of poetry, but also as a discussion starter about authenticity, oral tradition, and the formation of national identity.

Finnish has about six million speakers worldwide. The Department of Scandinavian regularly offers both Finnish language courses and courses in Finnish Culture and History. Numerous editions of the Kalevala are held by the University Library beginning with an important translation into German from 1852, kept in The Bancroft Library and contemporary with the publication of the later editions of German folklore collected by the Brothers Grimm. Other editions within the Library include a 1965 Finnish text which features Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s paintings, and, beyond English, translations into languages such as French, Yiddish, Hungarian, and Hindi.

Contribution by Lotta Weckström

Lecturer, Department of Scandinavian

Title: Kalevala

Title in English: Kalevala

Author: Lönnrot, Elias, 1802-1884, editor.

Imprint: Helsingissä, 1849.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Finnish

Language Family: Uralic, Finno-Ugric

Source: The HathiTrust Digital Library (Harvard University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011532640

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Kalevala. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1983.

- Kalevala. Liitteenä kaksikymmentäneljä kuvaa Akseli Gallen-Kallelan maalauksista. Helsinki: Otava, 1965.

- The Kalevala; or, Poems of the Kaleva District. Compiled by Elias Lönnrot. A prose translation with foreword and appendices by Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Kalevala; a Finn nemzeti hősköltemény. Finn eredetiből fordította: Vikár Béla. Translated into Hungarian. Budapest, Magyar Élet Kiadása, 1943.

- Kalewala, des national-epos der Finnen, nach der zweiten Ausgabe ins deutsche übertragen von Anton Schiefner. Helsingfors: J.C. Frenckell & Sohn, 1852.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Panjabi

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Panjabi (also written Punjabi) is an Indo-Aryan language with about 125 million speakers in South Asia and beyond. With most Panjabi speakers living in the Pakistani province of Panjab and the neighboring Indian state of the same name, it also has a large diaspora of speakers all over South Asia and beyond, especially in Great Britain and Canada. Panjabi is written in the Arabic script in Pakistan and in the Gurmukhi script in India.

With beginnings in the 13th century, one striking feature of Panjabi literature is the large number of ballads of unrequited love. Of these, few have been as popular as the love story of Hir and Ranjha, often just referred to as Hir (pronounced as Heer), whose tragic love story was given poetic form by a number of poets through the centuries.

Dhaidu Ranjha was the youngest and handsomest of eight brothers and two sisters. He was the spoilt darling of his parents which made his older brothers jealous. On the death of the parents the brothers divided up the farmland among themselves giving Ranjha the worst fields. Matters were made worse by the hostility of Ranjha’s sisters-in-law, who were fed up with the young women of the village swooning over their good-for-nothing brother-in-law. During an argument over food one day they insulted and taunted him and dared him to marry Hir, the beautiful daughter of the powerful Sial clan, if he had such a high opinion of himself.

Ranjha left his house in a huff vowing never to return and traveled all day until he was dead tired. He came across a throne in a beautiful garden and stretched himself on it and went to sleep. He was soon awakened by an indignant but radiantly beautiful young woman and her pretty companions. This was none other than Hir who angrily wanted to know why this stranger was sleeping on her throne in her private garden. However, when a few words were exchanged it was love at first sight for both of them. Ranjha decided to become a herdsman of Hir’s family’s water buffaloes in order to stay near her.

Hir’s family soon found out about their secret meetings and decided to marry her off into the Khera family that belonged to another powerful clan of the region. Hir and Ranjha were devastated and Ranjha, having decided to renounce the world, went to the monastery of Bal Nath, a master of the Nath sect of yogis and became a disciple. He began wandering as a mendicant only one day to knock on the door of Hir’s in-laws. The lovers resumed their secret trysts only to be found out again. This time the scandal was even bigger and more dangerous as the honor of two powerful clans was involved. Nevertheless, Hir’s family reluctantly agreed to allow Hir and Ranjha to marry. However Kaido, Hir’s maternal uncle could not bear the dishonor brought to the family, and on the day of the wedding killed Hir by making her eat a poisoned confection. When Ranjha came to the house and saw what had happened he immediately ate the rest of the poisoned confection at last uniting with his beloved in death if not in life.

The earliest extant version of Hir was composed by the poet Damodar (1486-1568) in the early 16th century. Other versions were produced by various poets over the centuries yet few reached the fame and popularity of Waris Shah’s version which continues to be sung and enjoyed to this day.

Born in 1722 in the town of Jandiala Sher Khan in present-day Pakistan, Waris Shah (also spelled Vāris̲ Shāh and Warisa Shaha) became the disciple of Hafiz Ghulam Murtaza, a Qadiri-Chisti Sufi master from the city of Qasur. After completing his education, Waris Shah settled in the village of Malka Hans, where according to tradition in 1766 Waris Shah wrote his version of Hir after his own experience of unrequited love. The beautiful language and refined sentiments of Waris Shah’s Hir made it an instant success, especially among Sufi and other religious circles who saw it as an allegory of the mystical path of spiritual realization and the soul’s yearning for union with the divine. One interesting feature of Waris Shah’s Hir is a detailed and appreciative description of the spiritual traditions of the Nath yogis highlighting the ecumenical vision of Waris Shah and his belief in the universality of love and its spiritual grace. It was for this reason that during the Partition riots of 1947 when the famous contemporary poet Amrita Preetam left her hometown of Lahore on a train heading to Delhi, she composed a poem of lament addressed to Waris Shah asking him to look at his strife-torn Panjab and open another page of the book of love.

As for Hir and Ranjha, while historians may doubt their existence the tomb in which both are reputedly buried continues to be a destination for star-crossed lovers, Sufi and other spiritual aspirants, and all those drawn to the grace of love.

UC Berkeley has offered instruction in Panjabi since the 1980s where introductory and intermediate Panjabi is taught in the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies. The current Panjabi instructor is Ms. Upkar Ubhi who has been teaching Panjabi on campus since 1998.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Hir Ranjha

Title in English: The Adventures of Hir and Ranjha

Author: Vāris̲ Shāh, 1722–1798.

Imprint: n/a

Edition: n/a

Language: Panjabi

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: Punjabi Kavita

URL: https://www.punjabi-kavita.com/Waris-Shah.php

Other online editions:

- The Adventures of Hir and Ranjha translated in to English by Charles Frederick Usborne, 1874 – 1919. (University of Heidelberg)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Hīra / Wārasashāha. Ammritasara: Bhāī Catara Siṅgha Jīwana Siṅgha, [19–]. In Panjabi (Gurmukhi script).

- Hīr Vāris̲ Shāh / Faqīr Muḥammad Faqīr; mushkil lafẓāṉ da tarjamah, Sult̤ān Khārvī. Lāhaur: Taḵẖlīqāt, 2012. In Panjabi (Arabic script).

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Hungarian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Magda Szabó (1917-2007) was a Hungarian novelist, known as the most translated Hungarian author. She worked in multiple genres, including drama, poetry, short stories, and memoirs. For this exhibition, we chose her 1987 novel Az ajtó (“The Door”) for several reasons, first she was repressed as a result of Stalinist excesses. According to a book review of another recently novel only recently translated into English, “her fiction shows the travails of modern Hungarian history from oblique but sharply illuminating angles.”[1] Second, the complex relations between the main characters of Az ajtó: Magda, her husband, and Emerence, the woman helper with an adopted dog, juxtaposed with who is in charge and how the relationship will evolve leads to a creation of a layered narrative. The layered narrative represents a mesmerizing self-weaving quilt of time and contextual protests.[2] As a young poet she won her country’s chief literary honor, the Baumgarten Prize, in 1949. On the same day, the communist regime cancelled this award to a class enemy. She lost her civil- service job, went to teach in a primary school, and only began to publish novels a decade later. Novels such as Az ajtó and Pilátus (“Iza’s Ballad”) are entangled with public upheavals from the repressive governments and Nazi occupation of the 1930s and 1940s, to the sudden annihilation of Hungary’s Jews, and the soul-sapping compromises and betrayals of the Stalinist era.

Called Magyar by its speakers, Hungarian is the language of Hungarians (Magyarok) and is the official language of the Republic of Hungary. It is spoken by over 10 million people in Hungary and also by approximately 3 million ethnic Hungarian minorities in parts of the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and other areas bordering Hungary. Hungarian belongs to the Ugric branch of Finno-Ugric languages. Hungarian also has loan words from Germanic, Slavic and Turkic groups of languages. According to Oxford’s International Encyclopedia of Linguistics International Encyclopedia of Linguistics (2nd ed.), Hungarian’s status is described as follows, “Until the end of the 18th century, the status of Hungarian in the juridical, educational, and even literary spheres was at best that of a lesser rival to Latin, and then to German. With the deliberate establishment of the standard literary language, and the prodigious output of the golden age of Hungarian belles-lettres (roughly 1780–1880), dialectal variation was winnowed out. At present, the primary internal variation lies in the contrast of rural vs. urban standard; the latter is roughly equivalent to the speech of Budapest, where one-fifth of the population resides.”[3]

Hungarian was also one of the principle languages of the multiethnic, multilingual Austro-Hungarian Empire since its establishment in 1801. In her essay “The History of the Book in Hungary,” Bridget Guzner notes, “The earliest Hungarian written records are closely linked to Christian culture and the Latin language. The first codices were copied and introduced by travelling monks on their arrival in the country during the 10th century, not long after the Magyar tribes had conquered and settled in the Carpathian Basin. The first incunabula known as Chronica Hungarorum (“Chronicle of Hungarians”) was published in 1473 by András Hess.”[4] According to The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance, “Scholarly study of the Hungarian language began in 1539 with the publication of Pannonius’ Grammatica Hungaro-Latina.”[5] Until the end of the 18th century, the principal language of Hungarian literature was Latin, which was the language of the markedly literary court of Matthias Corvinus. The most important writers of Latin in Hungary were János Vitéz, Pannonius (whose poetry included epigrams, panegyrics, and epics), the Italian Antonio Bonfini (who wrote an important history of Hungary, the Rerum Hungaricarum decades IV, Basel, 1568), and the Hungarian Sambucus, who wrote a continuation of Bonfini’s history. In the Hungarian language, the most influential works were a series of translations of the Bible into Hungarian. The first great lyric poet of Hungary was Valentine Bálint Balassi (1554–95).”[6]

At UC Berkeley, Hungarian is currently taught by Eva Szoke in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, but the credit for creation of Hungarian language teaching program on campus can be given to Ms. Agnes Mihalik, who arrived at UC Berkeley in 1982. Outside the Hungarian language program, Professor Jason Wittenberg and Professor-Emeritus Andrew Janos, both from the Department of Political Science, specialize in Central and Eastern Europe with a focus on Hungary.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

- “After 50 years, a Hungarian novel is published in English,” The Economist (February 28, 2019, (accessed 6/12/20)

- “The Hungarian Despair of Magda Szabó’s ‘The Door’,” by Cynthia Zarin. The New Yorker (April 29, 2016) (accessed 6/12/20)

- International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. William J. Frawley, ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. (accessed 6/12/20)

- “The History of the Book in Hungary” by Bridget Guzner in The Oxford Companion to the Book. Michael F. Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. (accessed 6/12/20)

- The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Gordon Campbell, ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. (accessed 6/12/20)

- Ibid.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Az ajtó

Title in English: The Door

Author: Szabó, Magda, 1917-2007

Imprint: Budapest: Magvető, 1987.

Edition: 1st

Language: Hungarian

Language Family: Uralic, Finno-Ugric

Source: Digitális Irodalmi Akadémia

URL: https://reader.dia.hu/document/Szabo_Magda-Az_ajto-889

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Az ajtó. Budapest: Magvető, 1987.

- The Door. Translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix; Introduction by Ali Smith. New York, NY: New York Review Books, 2015.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Ancient Greek

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns driven time and again off course, once he had plundered the hallowed heights of Troy.” So begins the epic tale of Odysseus, “the man of twists and turns” and king of Ithaca who, after he and his fellow Greeks achieved victory over the kingdom of Troy (a campaign recounted in the Iliad), sets off on his return voyage told in the Odyssey (“Ὀδύσσεια”).[1] That trip, which should have taken no more than a few weeks, becomes instead a journey of ten years as Odysseus and his men are confronted by storms, creatures of all kinds, and interventions by the gods.

The fate of Odysseus’ household on the island of Ithaca, located off the western coast of Greece, is the focus of the first part of the Odyssey. In the absence of Odysseus, his house has fallen under assault by a gluttonous group of men, the “suitors”, who rival one another for the hand of his faithful wife, Penelope, as they linger day after day, taking advantage of the family’s hospitality. His son, Telemachus, on the cusp of manhood, sets out for news of Odysseus, but returns home without certain information while the suitors plot his murder.

Well into the text, Odysseus describes the circumstances of his much delayed return. Sailing homeward from Troy, the 12 ships bearing Odysseus and his countrymen are hurled off course by a storm and a series of fantastic events begins. They survive the land of the Lotus-eaters, where they nearly succumb to forgetfulness after consuming the potent lotus plant, and then land on the island of the one-eyed Cyclopes. One Cyclops, Polyphemus, begins to devour Odysseus’ companions before the cunning Odysseus and his men take up a fiery stake and put out the creature’s single eye, escaping to their ship, and earning the wrath of Polyphemus’ father, the god Poseidon. Blown off course again, the group is attacked by the Laestrygonians, boulder-throwing giants, who destroy all of the ships but that of Odysseus and consume their crews. Odysseus’ ship next lands on the island of Circe, a sorceress who transforms Odysseus’ comrades into swine, brings Odysseus to her bed, and keeps him with her for a year. Following Circe’s release of Odysseus and his men, Odysseus makes a brief descent into the underworld, where he encounters a variety of dead including comrades who fought in the Trojan War, Heracles, his own mother, and the prophet Tiresias, who foretells his journey home. Returning to the surface and sailing onward, Odysseus has his men tie him to the ship’s mast while they plug their ears to avoid the tempting and deadly cry of the Sirens. After further events that result in the destruction of his ship and his remaining men, Odysseus reaches the island of the nymph Calypso, who holds him there as her lover for seven years.

Finally, Odysseus returns to Ithaca, where he had last stepped foot 20 years before. Observing the behavior of the suitors firsthand while disguised as a beggar, he crafts a plan: He blocks the doors of the hall, and with his son Telemachus at his side, assails the suitors with arrows and runs them through with spears while the goddess Athena protects him from the suitors’ weapons. Having slaughtered the abusive lot, Odysseus and Penelope are at last reunited.

According to ancient tradition, the Iliad and the Odyssey were both the poetic creations of a blind poet named Homer. Although Homer may be a fictitious person, these epic poems, or parts of them, must have been sung for some time by actual poets who knew them from memory at a time when writing was non-existent in Greece. Probably in the 8th century BC, the poems were written down for the first time following the Greeks’ borrowing of the Phoenician alphabet. The Iliad and the Odyssey were read throughout antiquity, and further served as a major point of reference for Greek works across genres, and, in Latin, most importantly provided a source of inspiration for the creation of the Aeneid, the epic foundation story of the founding of Rome which the poet Virgil composed in the 1st century BC.

Along with other myths, many scenes from the Homeric epics were taken up within ancient visual culture. One of the earliest examples is the blinding of Polyphemus, painted in the 7th century BC on the well-known Eleusis Amphora, which was used as the container for a child’s burial. Much later, together with many other aspects of culture which the Romans adopted from the Greeks, the Odyssey became represented in Roman art. The finest examples include the 1st century BC Odyssey Landscapes which decorated a luxurious house in Rome, and the 1st century AD sculpture groups within a grotto at the villa of the emperor Tiberius at Sperlonga, on the coast between Rome and Naples.

The Odyssey was copied and recopied through handwritten manuscripts in the Middle Ages, and in 1488 the first print edition was produced in Florence. As one of the classic texts of European, and indeed world literature, innumerable editions in Greek and in translation have been published since then. In the 20th century and beyond, the story of Odysseus has continued to influence literary and popular culture, from James Joyce’s 1922 Ulysses (the Latinized form of “Odysseus”) to the 2000 film O Brother, Where Out Thou, in which George Clooney plays “Ulysses Everett McGill”. The themes of the Odyssey are enduring: U.S. military veterans returning from recent wars in the Middle East have read the Iliad and the Odyssey within discussion groups and found parallels between their experiences and that of the war veteran Odysseus.[2] In 2018, readers from around the globe voted the Odyssey to the top of the list in the BBC poll, “100 Stories that Shaped the World”.[3]

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library possesses an excellent selection of early editions of the Odyssey beginning with an example printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius in 1504. In addition, seven Egyptian papyri from the 2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD in The Bancroft Library’s Center for the Tebtunis Papyri preserve handwritten fragments or quotations from the Odyssey in Ancient Greek. One, for example, from the late 1st or early 2nd century AD and recovered from a house at Tebtunis, contains a fragment from Book 11 of the Odyssey which describes Odysseus’ journey to the underworld. Aside from modern editions in Ancient Greek, the University Library owns numerous translations in English and a wide variety of other languages such as Italian, Icelandic, Russian, Turkish, and Hebrew.

Ancient Greek, along with Latin, have been offered at UC Berkeley since the university’s founding in 1868, and originally constituted required subjects for the BA degree. Greek emerged as its own department when a departmental structure was established in 1896, eventually joining the department of Latin to form a new Classics department in 1937. Today, Homer is taught regularly within the Classics department in both Ancient Greek and in translation.[4]

Contribution by Jeremy Ott

Classics and Germanic Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1996. Book One, lines 1-3.

- Ring, Wison. “‘Homer Can Help You’: War Veterans Use Ancient Epics to Cope,” AP News (March 13, 2018) (accessed 6/8/20)

- Haynes, Natalie . “The Greatest Tale Ever Told?,” BBC News (

- UC Berkeley Department of Classics – History, https://classics.berkeley.edu/about/department-history

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Ὀδύσσεια

Title in English: Odyssey

Author: Homer

Imprint: Venitiis : [Publisher not identified], secundo cale[n]das nouem, 1504.

Edition: 1st

Language: Ancient Greek

Language Family: Indo-European, Greek

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Northwestern University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102392919

Other Online Resources:

Digitized Papyri in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri containing fragments or quotations of the Odyssey:

- P.Tebt.0270. Possibly a fragment of a grammar; lines 2-6 contain a quotation from the Odyssey, book 18, line 130.

- P.Tebt.0271 Recto. Fragment of Hesiod’s Catalog of women (the Tyro passage); lines 2-3 are identical to Homer’s Odyssey, Book 2, lines 249-250.

- P.Tebt.0696. Fragments from the Odyssey, Book 1.

- P.Tebt.0431. Fragments of the Odyssey, Book 11.

- P.Tebt.Suppl.01,032-01,033. Fragments of the Odyssey, Book 12.

- P.Tebt.0432. Fragment from the Odyssey, Book 24.

- P.Tebt.0697. Lines from Books 4 and 5 of the Odyssey.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Homērou Ilias = Homeri Ilias. Venice: Aldus, 1504.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Classical Chinese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

題名雁塔代有其人

In every generation there are those who inscribe

their names on the Wild Goose Pagoda.

In 629, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang journeyed to the west in search of religious texts. Sixteen years later he returned to the Tang capital at Chang’an (modern Xi’an) with hundreds of Sanskrit sutras that would have to be rendered into Chinese. Emperor Gaozong invited the monk to base his translation project at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda on the grounds of Ci’ensi, a temple with strong ties to the throne and accordingly adorned with religious sculpture and textual engravings of the highest quality.

At that time, successful civil-service examinees were known to write their names on the pagoda walls with brush and ink. This custom evolved into something more durable in the centuries following the dynasty’s collapse in 907. Chang’an then lost its preeminence and much of its population, although it remained a site of historical and cultural interest. Visitors invariably stopped at the pagoda to view the surroundings from its upper stories. Some left their autographs there as well, carved over the Buddhas and divine attendants in the lintels surmounting the four entrances to the building—a practice that might have alluded to past privilege and accomplishment, but also to the city’s diminished status and the uncertain course of power.

This rubbing and dozens of others were given to the East Asian Library by the bequest of Woodbridge Bingham (1901–86), professor of history and founder of the Institute of East Asian Studies. Before the establishment of the East Asian Library, the campus community depended on faculty like Bingham, Ferdinand Lessing, and Delmer Brown, to help develop its collections: they left for sabbaticals abroad with lists of desiderata; once overseas, they sacrificed research hours haunting bookstores, searching out collectors willing to sell, wrangling with customs officials. At the end of their careers, many left their own collections to the university, building on the foundation that they had helped lay.

Contribution by Deborah Rudolph

Curator, C. V. Starr East Asian Library

Title: Dayan ta fo ke ji ti ming 大雁塔佛刻及題名

Title in English: Reliefs and inscriptions from the lintels of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda

Authors: Anonymous (artwork); multiple authors (textual inscriptions)

Imprint: 20th-century rubbing of Tang dynasty pictorial relief, with textual inscriptions dating from the Song through the Ming dynasties

Language: Chinese

Language Family: Sino-Tibetan

Source: C. V. Starr East Asian Library (UC Berkeley)

URL1: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/stonerubbings/ucb/images/brk00024200_32b_k.jpg

URL2: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/stonerubbings/ucb/images/brk00024198_32b_k.jpg

Other online editions:

- The East Asian Library’s rubbings of the lintels have been digitized and added to its online catalog of the rubbings collection, at http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/EAL/stone/index.html

- A series of photographs and details of the reliefs can be found on the blog site sina.com, at http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_91ea73640102x92v.html (accessed 6/1/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Amharic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

With over 2,000 vernacular languages, sub-Saharan Africa includes approximately one-third of the world’s languages.[1] Many of these will likely disappear in the next hundred years, displaced by dominant regional languages like Amharic.

Amharic, alternately known as Abyssinian, Amarigna, Amarinya, Amhara, or, simply, Ethiopian, is a Semitic language spoken by over 25 million people. It is part of the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language group, which spans, as the name suggests, two continents, primarily West Asia as well as North Africa and the Horn of Africa. In the 13th century, it evolved as a spoken language and replaced Ge’ez as the common means of communication in the imperial court where it was referred to as the language of the king.[2] Today, Amharic is spoken as the first language (L1) by the Amhara of the northwest Highlands of Ethiopia. As the official language of Ethiopia, it has become the lingua franca of the country.[3]

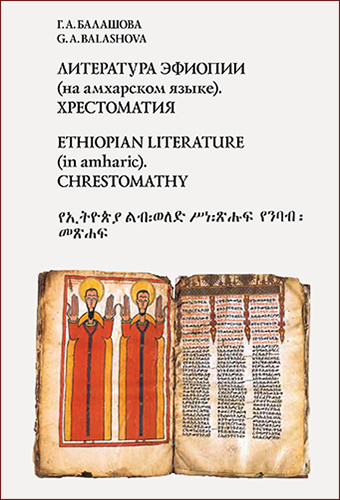

Beyond Amharic’s inherent importance in the realm of politics, education, and business as a result of its privileged status as the official language of Ethiopia, it is also a major literary language in the country. Early (pre-20th century) Ethiopian literature often took on religious themes and was published in the ancient Semitic language of Ge‘ez. However, by the turn of the 20th century, literary publications in Amharic became more common, signaling the language’s ascent. The featured text here, Ethiopian Literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy, a collection of seventeen samples of Ethiopian literature by various authors, captures the expansion of Amharic influence in literary publications. The collection covers one-hundred years of Ethiopian literary prose beginning with “Story Born at Heart” by Afewerk Ghebre Jesus, originally published in 1908, up to the early 2000s with a piece by one of the great modern Ethiopian writers, Adam Reta. The collection, generously adorned with illustrations throughout, was designed for students of Amharic philology.

At UC Berkeley, based on research interest and student demand, especially from heritage students, with Title VI funding through the Center for African Studies, Amharic language study (at the elementary and intermediate levels) has been offered since the fall of 2019. Students enrolled in Amharic are among the few in the whole of the United States formally studying the language and are at the vanguard in recognizing Africa’s increasing importance demographically, socially, and culturally.[4]

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Moseley, Christopher, and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, 2010.

- Meyer, Ronny. “Amharic as Lingua Franca in Ethiopia.” Lissan: Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 20 1/2 (2006).

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (accessed 5/16/20)

- Saavedra, Martha and Leonardo Arriola. “UC Berkeley Needs to Support African Language Programs” Daily Californian (February 22, 2019) (accessed 5/16/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Ethiopian Literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy

Author: Galina (Galina Aleksandrovna) Balashova, compiler.

Imprint: Lac-Beaport, Quebec : MEABOOKS Inc., 2016. (Baltimore, Md. : Project MUSE, 2015.)

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Amharic

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, South Semitic

Source: Project Muse

URL: https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.berkeley.edu/book/48900 (UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Ethiopian literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy / G.A. Balashova, comp. Lac-Beauport, Quebec: MeaBooks Inc, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Romanian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

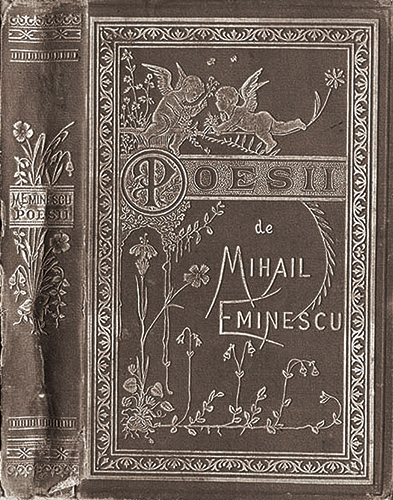

Mihail Eminescu, pseudonym of Mihail Eminovici, (1850-1889), was a poet who transformed both the form and content of Romanian poetry, creating a school of poetry that strongly influenced Romanian writers and poets in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eminescu was educated in the Germano-Romanian cultural centre of Cernăuţi (now Chernovtsy, Ukraine) and at the universities of Vienna and Berlin, where he was influenced by German philosophy and Western literature. In 1874, he was appointed school inspector and librarian at the University of Iaşi but soon resigned to take up the post of editor in chief of the conservative paper Timpul. His literary activity came to an end in 1883, when he suffered the onset of a mental disorder that led to his death in an asylum.

Eminescu’s talent was first revealed in 1870 by two poems published in Convorbiri literare, the organ of the Junimea society in Iaşi. Other poems followed, and he became recognized as the foremost modern Romanian poet. Mystically inclined and of a melancholy disposition, he lived in the glory of the Romanian medieval past and in folklore, on which he based one of his outstanding poems, “Luceafărul” (1883; “The Evening Star”). Eminescu’s poetry has a distinctive simplicity of language, a masterly handling of rhyme and verse form, a profundity of thought, and a plasticity of expression which affected nearly every Romanian writer of his own period and after. His poems have been translated into several languages, including an English translation in 1930, but chiefly into German. Among his prose writings, apart from many studies and essays, the best-known are the stories “Cezara” and “Sărmanul Dionis” (1872).[1]

Romanian, or Rumanian, is one of the Romance languages that is spoken in Eastern Europe, principally in Romania and the Republic of Moldova. It evolved in very different circumstances from its western sister languages such as Spanish and Italian, and was profoundly affected by the Orthodox Church, the Greek and Slavonic languages, and the Ottoman Empire. It has a lexical affinity with Old Church Slavonic.[2] For the latter half of the 20th century, UC Berkeley had a very active program in Romanian. The Russian-born Romance etymologist and philologist Yakov Malkiel, who taught at Berkeley for over 55 years, mentored students who specialized in Romanian linguistics. In 1947, he became founding editor of the prestigious journal Romance Philology which is still published today. ProQuest’s Dissertation & Theses lists more than 227 doctoral dissertations from UC Berkeley that are related in one way or another to Romania and the Romanian language.[3] However in light of funding cuts, Romanian has not been taught at Berkeley in over two years. Graduate students in the interdisciplinary Romance Languages and Literatures (RLL) program may choose Romanian as one of their languages.[4]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- “Mihail Eminescu: Romanian Poet” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. (accessed 5/1/20)

- Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998.

- Proquest Dissertations & Theses (accessed 5/1/20)

- Romance Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley (accessed 5/1/20)

- Cimpoi, Mihai (coord.), 2020, Eminescu—Opere (vol. I-VIII), Editura Gunivas.On the matter of the assassination and those involved:

- Lepuş, Miruna, 2021, Dosarele de interdicţie ale lui Mihai Eminescu, Editura Cartex.

- Barbu, Constantin, 2008, Codul invers, Editura Sitech.

- Georgescu, Nicolae, 2014, Boala şi moartea lui Eminescu, Editura Floare Albastră.

- Georgescu, Nicolae, 2011, Eminescu: ultima zi la Timpul, Editura ASE.

- Vuia, Ovidiu, 1997, Despre boala şi moartea lui Mihai Eminescu—studiu patografic, Editura Făt-Frumos.

On the matter of the birthdate:

- Marin, I.D., 1979, Eminescu la Ipoteşti, Editura Junimea.

- Ştefanelli, Teodor V., 1983, Amintiri despre Eminescu, Editura Junimea.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Poezii complecte

Title in English: Complete Poems

Author: Eminescu, Mihai, 1850-1889.

Imprint: Iași, Editura librărieĭ frațiĭ Șaraga [188-?].

Edition: n/a

Language: Romanian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Harvard University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100545314

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Poezii / M. Eminescu ; antologie, prefață și tabel cronologic de George Gană ; ilustrați de Dumitru Verdeș. București : Editura Minerva, 1999.

- Poezii / M. Eminescu ; ediție critică de D. Murărașu. București : Editura Minerva, 1982. v.1-3

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)