Tag: digital humanities

Go from Analog to Digital Texts with OCR

A collection of digitized texts marks the start of a research project — or does it?

For many social sciences and humanities researchers, creating searchable, editable, and machine-readable digital texts out of heaps of paper in archival boxes or from books painstakingly sourced from overlooked corners of the library can be a tedious, time-consuming process.

Scholars using traditional methodologies may find it advantageous to have a digital copy of their source material, if only to be able to more easily search through it. For anyone who wants to use computational methods and tools, converting print sources to digital text is a prerequisite. The process of converting an image of scanned text to digital text involves Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. New developments in campus services are providing additional options for researchers who wish to prepare their texts this way.

What resources does UC Berkeley offer to convert scans to digital text?

- For basic needs, try the Library’s scanners.

- For documents with complex layouts or for additional language support, ABBYY FineReader with Berkeley’s OCR virtual desktop is a solution.

- Finally, Tesseract can handle large scale OCR projects.

Books and simple documents: library scanners with OCR software

All of the UC Berkeley libraries, including the Main (Gardner) Stacks, have at least one Scannx scanner station with built-in OCR software. This software automatically identifies and splits apart pages when you’re scanning a book, and it performs OCR on any text it can identify. You can save your results as a “Searchable PDF” (with embedded OCR output) or as a Microsoft Word document, or you can save page images as TIFF, JPEG, or PDF files (omitting digitized text). For book scanning or simple document scanning, the library scanners can take you from analog to digital in a single step.

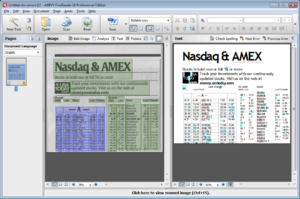

Complex layouts or language support: ABBYY FineReader and Berkeley Research Computing’s OCR virtual desktop

If your source material has a complex layout (like irregular columns, embedded images, and/or tables that you want to continue to edit as tables) or uses a non-Latin alphabet, ABBYY FineReader OCR may get you better OCR results. FineReader supports Arabic, Chinese, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Japanese, and Thai, among other languages.

On campus, FineReader is available on computers in the D-Lab (350 Barrows). From off campus, the OCR virtual research desktop provided through Berkeley Research Computing’s AEoD service (Analytic Environments on Demand, pronounced “A-odd”) allows users to log into a virtual Windows environment from their own laptop or desktop computer anywhere there’s an internet connection. If you’re visiting an archive and aren’t sure that your image capture setup is getting good enough results to use as OCR input, you can log into the OCR virtual research desktop and try out a couple samples, then refine your process as needed. You can also work on your OCR project from home, or on nights and weekends when campus buildings are closed. To use the OCR virtual research desktop, sign up for access at http://research-it.berkeley.edu/ocr.

FineReader is not generally recommended for very large numbers of PDFs because each conversion must be started by hand. However, if you don’t need to differentiate the origin of your various source PDFs (e.g., if your text analysis will treat all text as part of a single corpus, and it doesn’t matter which of the million PDFs any particular bit of text originally came from), you might be able to use FineReader by creating one or more “mega-PDFs” that combine tens or hundreds of source PDFs and letting it run over a long period of time. At a certain point, however, Tesseract might be a better choice.

OCR at scale: Tesseract on the Savio high-performance compute cluster

If you have thousands, hundreds of thousands, or millions of PDFs to OCR, a high-powered, automated solution is usually best. One such option is the open source OCR engine Tesseract. Research IT has installed Tesseract in a container that you can use on the Savio high performance computing (HPC) cluster. For researchers who are less comfortable with the command line, there is also a Jupyter notebook available that provides the necessary commands and “human-readable” documentation, in a form that you can run on the cluster. Any tenure-track faculty member is eligible for a Faculty Computing Allowance for using Savio. For graduate students, talk to your advisor about signing up for an allowance and receiving access.

No matter how large or small your OCR project is, UC Berkeley has the perfect tool for you in scanning equipment, ABBYY FineReader, or Tesseract. Happy converting!

Related Event: From Sources to Data: Using OCR in the Classroom

March 16, 2017

10:30am to 12:00pm

Open to: All faculty, graduate students, and staff

Questions?

Quinn Dombrowski, Research IT quinnd [at] berkeley.edu

Stacy Reardon, Library sreardon [a] berkeley.edu

Thank you to Cody Hennesy for suggestions. Cross posted on the D-Lab blog and the Research IT blog.

Gallica Gives

Online since 1997, Gallica remains one of the major digital libraries available for free on the Internet. With more than 12 million high-resolution digital objects from the collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) as well as from hundreds of partner institutions, it includes books, journals, newspapers, manuscripts, maps, images, audio files, and more. The illustration above “Ça, mon enfant, c’est du pain.. [That, my child, is bread…]” by Fernand-Louis Gottlob was published in one of the first issues of the weekly satirical magazine L’Assiette au beurre (1901-1936) which is also held in print at UC Berkeley. Committed to the ever-evolving needs of its user community, Gallica’s social media outlets include Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and even a BnF app.

Where to Find the Texts for Text Mining

Text mining, the process of computationally analyzing large swaths of natural language texts, can illuminate patterns and trends in literature, journalism, and other forms of textual culture that are sometimes discernible only at scale, and it’s an important digital humanities method. If text mining interests you, then finding the right tool — whether you turn to an entry-level system like Voyant or master a programming language like Python — is only a part of the solution. Your analyses are only as strong as the texts you’re working with, after all, and finding authoritative text corpora can sometimes be difficult due to paywalls and licensing restrictions. The good news is the UC Berkeley Libraries offer a range of text corpora for you to analyze, and we can help you get your hands on things we don’t already have access to.

The first step in your exploration should be the library’s Text Mining Guide, which lists text corpora that are either publicly accessible (e.g., the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America newspaper collection) or are available to UCB faculty, students, and staff (e.g., JSTOR Data for Research). The content of these sources are available in a variety of formats: you may be able to download the texts in bulk, use an API, or make use of a content provider’s in-platform tools. In other cases (e.g., ProQuest Historical Newspapers), the library may be able to arrange access upon request. While the scope of the corpora we have access to is wide, we are particularly strong in newspaper collections, pre-20th century English literature collections, and scholarly texts.

What happens if the library doesn’t have what you need? We regularly facilitate the acquisition of text corpora upon request, and you can always email your subject librarian with specific requests or questions. The library will deal with licensing questions so you don’t have to, and we’ll work with you to figure out the best way to make the texts available for your work, often with the help of our friends in the D-Lab or Research IT . We also offer the Data Acquisition and Access Program to provide special funding for one-time data set purchases, including text corpora. Your requests and suggestions help the library develop our collection, making text mining easier for the next researcher who comes along.

Important caveats:

- Unless explicitly stated, our contracts for most Library databases and library resources (e.g., Scopus, Project MUSE) don’t allow for bulk download. Please avoid web scraping licensed library resources on your own: content providers realize what is happening pretty quickly, and they react by shutting down access for our entire campus. Ask your subject librarian for help instead.

- Keep in mind that many of the vendors themselves are limited in how, and how much access, they can provide to a particular resource, based on their own contractual agreements. It’s not uncommon for specific contemporary newspapers and journals to be unavailable for analysis at scale, even when library funding for access may be available.

Related resources:

- Library Text Mining Guide

- Library Data Acquisition and Access Program

- D-Lab Computational Text Analysis Working Group

- D-Lab Learn Python Working Group

Stacy Reardon and Cody Hennesy

Contact us at sreardon [at] berkeley.edu; chennesy [at] berkeley.edu

Digital Humanities for Tomorrow

Opening the Conversation About DH Project Preservation

By Rachael G. Samberg & Stacy Reardon

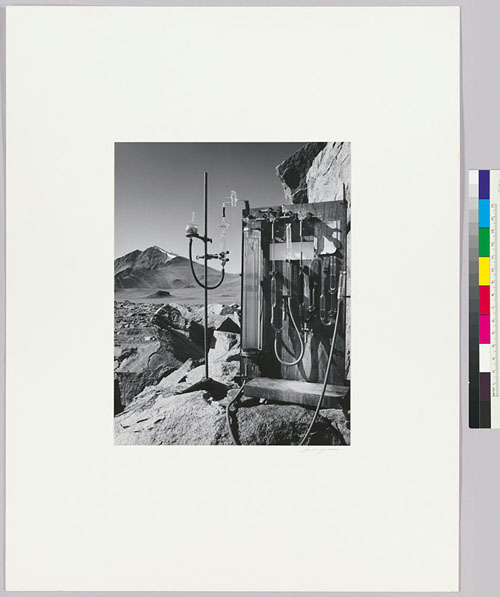

Digital Object Maker. Sayf, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

After intensive research, hard work, and maybe even fundraising, you launch your digital humanities (DH) project into the world. Researchers anywhere have instant access to your web app, digital archive, data set, or project website. But what will happen to your scholarly output in five years? In twenty-five? What happens if you change institutions, or institutional priorities shift? Will your digital project be updated or forced to close up shop? Who should ensure that your project remains available to researchers? Which departments should guide long-term sustainability of your research? Continue reading “Digital Humanities for Tomorrow”

Connect Your Scholarship: Open Access Week 2016

Open Access connects your scholarship to the world, and for the week of Oct. 24-28, the UC Berkeley Library is highlighting these connections with five exciting workshops and panels.

What’s Open Access?

Open Access (OA) is the free, immediate, online availability of scholarship. Often, OA scholarship is also free of accompanying copyright or licensing reuse restrictions, promoting further innovation. OA removes barriers between readers and scholarly publications—connecting readers to information, and scholars to emerging scholarship and other authors with whom they can collaborate, or whose work they can test, innovate with, and expand upon.

Open Access Week @ UC Berkeley

OA Week 2016 is a global effort to bring attention to the connections that OA makes possible. At UC Berkeley, the University Library—with participation from partners like the D-Lab, California Digital Library, DH@Berkeley, and more—has put together engaging programming demonstrating OA’s connections in action. We hope to see you there.

Schedule

To register for these events and find out more, please visit our OA Week 2016 guide.

- Digital Humanities for Tomorrow

2-4 pm, Monday October 24, Doe Library 303 - Copyright and Your Dissertation

4-5 pm, Monday October 24, Sproul Hall 309 - Publishing Your Dissertation

2-3 pm, Tuesday October 25, Sproul Hall 309 - Increase and Track Your Scholarly Impact

2-3 pm, Thursday October 27, Sproul Hall 309 - Current Topics in Data Publishing

2-3 pm, Friday October 28, Doe Library 190

You can also talk to a Library expert from 11 a.m. – 1 p.m. on Oct. 24-28 at:

- North Gate Hall (Mon., Tue.)

- Kroeber Hall (Wed.–Fri.)

Event attendance and table visits earn raffle tickets for a prize drawing on October 28!

Sponsored by the UC Berkeley Library, and organized by the Library’s Scholarly Communication Expertise Group. Contact Library Scholarly Communication Officer, Rachael Samberg (rsamberg@berkeley.edu), with questions.

Event: Editions Inside of Archives: Literary Editing and Preservation at the Mark Twain Project

I’m sharing this event announcement because it may be of interest to you.

The Literature and Digital Humanities Working Group, and the Americanist Colloquium, would like to invite you to join us at the following talk:

Editions Inside of Archives: Literary Editing and Preservation at the Mark Twain Project

Christopher Ohge

Thursday October 13th, 6.30pm

DLib Collaboratory, 350 Barrows Hall

The Mark Twain Papers & Project not only contains the largest collection of material by and about Mark Twain, it also employs several editors working toward a complete scholarly edition of Mark Twain’s writings and letters. The editors in the Project are sometimes involved in archival management, preservation, and “digital humanities” endeavors. Yet the goals of the archive both overlap with and diverge from those of a scholarly edition, especially in that editions produced by the Mark Twain Project use material from other archives, and considering the limit to which editorial work can faithful to physical manuscripts. Archival projects are sometimes done at the expense of editorial projects, and vice versa; each enterprise has its gains and losses.

Digital scholarly editing can also depart from more traditional print editorial enterprises. When editorial policy modifications occur simultaneously with the evolution of digital interfaces, what is an editor to do? Put another way, when “digitizing” an old book with a different editorial policy, is one obliged to “re-edit” the text or compromise about how to present the product of a different set of expectations for editing and designing scholarly editions? How do notions of readability and reliability change with concurrent technological innovations? I shall examine instances where the physical archive, the digital archive, and editions at the Mark Twain Project have illuminated common as well as new ground on reading, editing, and cultural heritage.

Event: HathiTrust Research Center Text Analysis Tools workshop

Digital Humanities and the Library

Are you a humanist working with digital materials to do your research? Are you carrying out your research or presenting your results using digital methods and tools? Are you teaching using digital tools and content? If you answered yes to any of these questions, then your work might be considered digital humanities.

Are you a humanist working with digital materials to do your research? Are you carrying out your research or presenting your results using digital methods and tools? Are you teaching using digital tools and content? If you answered yes to any of these questions, then your work might be considered digital humanities.

Digital humanities has been described as “dynamic dialogue between emerging technology and humanistic inquiry” (Varner, 2016). It is a term that is used to describe a domain within the humanities where researchers are doing most of their work using digital tools, content, and/or methods. Whether this work is partially or exclusively digital, this designation is a way to set these emerging practices apart from more traditional or “analog” ones, though there is no clear distinction.

The scope of digital humanities has been a hot topic in recent years, especially in relation to the library’s role in this new domain. What services does the library provide to digital humanists? What can the library do to support digital humanities on campus?

The Library has always provided services to researchers and will continue to provide those same services, as well as to expand their offerings to encompass new forms of research, publication, and teaching. It is not a question of libraries supporting one or the other. Digital humanities is still evolving, and the Library is evolving right along with it, continuing to offer collections, research support, and instruction in both traditional ways and new ones as this “dynamic dialogue” expands.

The Library collects and creates digital resources at the same time that it continues to build its analog collections. Myriad databases, data sets, and other digital resources are available through the Library catalog and website. In addition, our digitized special collections are available through Calisphere, which provides access to digital images, texts, and recordings from California’s great libraries, archives, and museums.

While the library is busy collecting and organizing digital resources, reference librarians are ready and willing to provide you with research help. The expertise that librarians have in connecting researchers to materials, designing research, and providing instruction on how to evaluate and use new content and tools continues to grow and expand in this new environment.

In addition, the library provides instruction to help those new to the digital humanities to learn about tools and skills needed to do this work. Many librarians have partnered with the D-lab in Barrows Hall on campus to provide instruction on citation management, metadata, and research data management. The D-lab also offers training in various programming languages and data tools, as well as consulting on research design, data analysis, data management, and related techniques and technologies. Library trainings and events are generally posted to the library events calendar.

The Library also works closely with the Digital Humanities @ Berkeley group (a partnership between Research IT and the Office of the Dean of Arts and Humanities) which support digital humanities events, trainings, course support, and graduate student and faculty projects. Their calendar lists talks, workshops, and other events designed to help move the DH community on campus forward.

Keeping the “dynamic dialogue” of digital humanities moving forward is a campus goal, and the relationship between digital humanities and the Library is an evolving one. We are hiring new librarians with digital humanities skills to further develop this relationship and expect to see more growth in the scope of the library’s involvement in digital humanities as the community on campus continues to expand.

Mary W. Elings

Head of Digital Collection, The Bancroft Library

Contact me at melings [at] berkeley.edu

Digital Humanities: Mapping Occupation

Quoted from the project website:

“Mapping Occupation, by Gregory P. Downs and Scott Nesbit, captures the regions where the United States Army could effectively act as an occupying force in the Reconstruction South. For the first time, it presents the basic nuts-and-bolts facts about the Army’s presence, movements that are central to understanding the occupation of the South. That data in turn reorients our understanding of the Reconstruction that followed Confederate surrender. Viewers can use these maps as a guide through a complex period, a massive data source, and a first step in capturing the federal government’s new reach into the countryside.

“From the start of the Civil War and through the 1870s, the U.S. Army remained the key institution that newly freed people in the South could access as they tried to defend their rights. While slaves took the crucial steps to seize their chance at freedom, soldiers helped convince planters that slavery was dead, overturned local laws and court cases, and in other ways worked with freed people to construct a new form of federal power on the ground.

“The army was central to the story of Reconstruction, yet basic information about where the Army was, in what numbers, and with what types of troops, has been difficult to find. Downs gathered this information from manuscript sources in the National Archives and other repositories in preparation for his book, After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2015). Mapping Occupation presents an expanded version of this information in an online interface and as a downloadable data. Downs and Nesbit then used these locations to create rough estimates of the Army’s reach and, importantly, the places from which freedpeople and others could reach the Army in order to bring complaints about outrages and other forms of injustice. The methods by which we created these estimates are discussed here.

“Mapping Occupation presents this history and geography in two ways: as a spatial narrative, guiding the user through key stages in the spatial history of the army in Reconstruction; and as an exploratory map, in which users are free to build their own narratives out of the data that we have curated here. Both afford visitors to the site important tools for mapping the Army’s reach in the Reconstruction South.”

Featured Book: Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope

I’ve just ordered a copy of Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope for the Library, but have also discovered that there is a pre-press version available online.

You can find more information about the book at the publisher’s website.

!["Ça, mon enfant, c'est du pain.. [That, my child, is bread...]" par Gottlob in L'Assiette au beurre (1901)](https://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/accounts/5279/images/assiette-au-beurre.jpg)