Tag: Bancroft

Q & A with Charles Faulhaber on his election to the Royal Spanish Academy

In September, Charles Faulhaber, former director of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, was elected to join 100 scholars and researchers as a foreign corresponding member of the Royal Spanish Academy, or Real Academia Española. Below are excerpts from a Q & A with Faulhaber.

1. What is it that fascinates you most about your work with medieval Spanish literature? How does it fit into the overall arc of your life as a scholar?

It’s the thrill of the hunt. I never know what I am going to find when I sit down in a library and ask to see a manuscript. I may find a text that is utterly unknown. I may find a manuscript of a text previously known only in printed form. When I look at a manuscript I am not looking for anything in particular. What I find is due to pure serendipity.

And I think that serendipity and chance have played major roles in my life as a scholar. It was pure chance that led me to spend junior year in Spain. It was pure chance that the first class I took in graduate school at Yale was on medieval Spanish literature. It was pure chance that one of my professors at the University of Wisconsin would become the director of the Hispanic Society of America and later ask me to catalog its medieval manuscripts.

2. After your busy and productive years as Director of the Bancroft Library, what are you relishing about retirement? What do you miss most about serving as Bancroft Director?

Retirement has given me the opportunity to concentrate on PhiloBiblon (a bio-bibliographical database of medieval texts from the Iberian Peninsula) with the kind of intensity that was simply not possible before. And, of course, it has made it possible to travel much more frequently, both for research trips to Spain and for pleasure, like my and my wife Jamy’s current trip to Greece.

What I miss most from Bancroft are the people, both inside and outside of the library. I still see most of my former Bancroft colleagues since I take a regular turn on the Reference Desk as a volunteer, but I do not see nearly as many of the Friends of the Bancroft Library as I would like.

3. Tell us about the work that earned you the honor of election to the Royal Spanish Academy.

Embarrassing as it is to admit it, part of this is sheer longevity. I have been studying medieval Spanish literature seriously for almost fifty years. I started out by examining the influence of Classical Latin rhetoric on medieval Spanish literature, but I became increasingly aware that my work was partial and incomplete because many important texts existed only as manuscripts that had never even been described, let alone transcribed. In order to study the literature you must first define the corpus.

I did not become fully aware of this until I was invited to catalog the medieval manuscripts of the Hispanic Society of America in 1978. The HSA, in New York, is the largest Spanish library outside of Spain. As a result of that work I was invited to take over the Bibliography of Old Spanish Texts, originally an in-house database of incunabula and pre-1500 manuscripts to provide lexical material for the Dictionary of the Old Spanish Language at the University of Wisconsin. That was in 1981. Since then I have been joined by a group of scholars whose collective efforts have created the PhiloBiblon database for the study of the primary sources of the medieval Iberian literatures — Spanish, Catalan, Galician, and Portuguese — and the individuals and institutions that created and disseminated them. PhiloBiblon currently has over 340,000 entries and has spurred a renewed interest in textual and manuscript studies.

4. What new or new-ish digital tools and resources in your field have opened up research possibilities that didn’t exist before? (And, are there any you’d like to see?)

For decades what used to be called “humanities computing” was practiced by a handful of scholars, but for most humanists the computer was simply a glorified typewriter. What changed it into the Digital Humanities was the explosion of digital resources, starting in the 1990s. The Berkeley Library played a pioneering role in this process under the leadership of former Berkeley librarians Daniel Pitti and Bernie Hurley. I became involved in it almost as soon as I came to Bancroft in 1995, with the Digital Scriptorium project to digitize medieval manuscripts.

However, my sense is that to date Digital Humanities is still more about potential than achievement. It is very difficult to point to a DH project and say, “This has really revolutionized our understanding of Cervantes or Shakespeare.” But DH is in its infancy. Of what use is a new-born baby?

In 1991 I gave a paper at a conference on medieval Spanish literature on desiderata for its study, focusing primarily on digital tools and databases. In 2011 I gave a retrospective paper on the same theme at a conference in Barcelona. Not one of the tools I envisioned 20 years earlier had been created. Why not? Principally lack of money. Humanities scholarship simply does not receive the same level of funding, by several orders of magnitude, as scientific research.

Exhibit: The Gift to Sing: Highlights of the Leon F. Litwack & Bancroft Library African American Collections

I’m sharing this announcement of Bancroft’s new exhibit:

The Bancroft Library just opened its fall/winter exhibition, The Gift to Sing: Highlights of the Leon F. Litwack & Bancroft Library African American Collections. Leon Litwack is a historian and legendary professor who taught here from 1964 to 2007. He won the Pulitzer Prize for History and the National Book Award for his 1979 book Been In the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. He has been collecting books relating to African American history and culture since the 1940s and his collection is now perhaps the best in private hands. Ultimately, it will be coming to The Bancroft Library but highlights, along with related material from Bancroft’s collection, will be on display until February.

Highlights from Professor Litwack’s collection include Bobby Seale’s copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a copy of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave inscribed by William Lloyd Garrison and Ida B. Wells’ incredibly rare and important pamphlet on lynching, The Red Record.

Bancroft highlights include the first printing of Phillis Wheatley’s collection of poems from 1773 and early works printed in California.

The Bancroft Library Gallery is open from Monday to Friday, 10-4.

http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library/current-exhibits

David Faulds

Curator of Rare Books and Literary Manuscripts

Social Problems During California’s Gold Rush Presaged Those We Face Today

by Louisa R. Brandt, an undergraduate student at UC Davis who spent her Summer 2015 break processing manuscripts at The Bancroft Library (originally posted to the “What’s New” blog on 2016/04/20)

Gold Rush-era letters, and others like them, are open for research at The Bancroft Library. Visit the library to conduct your own inquiries into the experiences of Californians living through past booms and busts.

As the Eastern United States met the West in the months and years following the 1848 gold discovery at Sutter’s Mill, California’s shores and gold-filled hills became riddled with problems the eager prospectors might have thought they had left behind: racial tension, concern over rainfall, economic disparities between neighbors, overcrowding and high rent. These sound familiar, don’t they?

At The Bancroft Library, recent acquisitions of letters sent from California during this widely-studied era illuminate through the voices of young men, both optimistic and pessimistic, how they saw this “land of opportunity” and tried to explain it to their relatives and friends back home. Although many of the letter writers in this collection are not famous, and some even unidentified, the aggregate of their experiences and descriptions paint an honest likeness of this not-so-foreign past.

The influx of prospective miners into California after January 1848 brought the racist stereotypes regarding the native population already common in the East to the forefront of western social interaction. Common claims of the day deriding the character of the Indians are seen in the December 25, 1852 letter by Abram Lanphear to his brother in New York as he calls the native population a “poor indolent lazy set of mortals” (BANC MSS 2015/12). Similar ideas drove the state military’s pursuit of revenge for the death of one sergeant during an altercation that had already left eight native people dead, as explained by Brigadier General Albert Maver Winn’s July 21, 1851 letter (BANC MSS 2015/16). Some men were not so blindly willing to believe the prejudice against Indians, and asserted that this hatred was sometimes used to cover for violence between whites. A Virginian miner in Butte County tells a friend of the “band of robbers who committed such wholesale & fiendish murders in our neighborhood” leaving victims with their “throats cut & arrows stuck all over them.” Despite the attempt to make the murders fit the Anglo perception of native warfare tactics, the author does believe that the Indians are blamed “probably falsly [sic]” (BANC MSS 2014/19). This method of exploiting the new immigrants’ fear and ingrained ideas of native people attacking was also used in San Francisco, as carpenter Christopher Toole notes that “the great trouble is with the indians but….the fault is not with indians it is with the whites” (BANC MSS 2015/19). That some people saw through efforts to make them believe in the evil of the native people mirrors today’s concerns over racial profiling.

Due to the need for water to wash gold from the gravel pulled from mines, and the fact that too much water made it impossible to reach the ore-rich hills, the amount of rain and river water was an important subject for men in the fields and in the cities. Miners writing from their claims often wished for a “wet winter” in order to have the rivers filled throughout the spring and summer months (BANC MSS 2014/12). When the rains came at an inopportune time, however, as was the case during the late winter of 1850, it created chaos as a dry February caused “such rush for the mines you never see in your life,” and the succeeding wet March sent the prospectors flooding back into cities (BANC MSS 2015/19). This dependence upon the rain is familiar to today’s Californians, who daily hear about the prolonged drought, and the possible flooding that could occur if the projected El Nino winter proves to be as strong as predicted. Even though many people do not rely solely on water for employment, the concern over water is unabated, and remains as common a topic of conversation today as it was during the Gold Rush.

Like most new careers, digging for gold held its fair share of monetary risk and depended on luck. A man identified only as “Charles” observed in 1850 that “99 out of 100” men get not a cent from mining (BANC MSS 2014/53). While some men struck it rich upon arrival, many were not so fortunate and spent months in squalid conditions. The different financial outcomes between men who dug for gold in the same areas proves just how random success was, and can be reflected in today’s business environment in which one new technology soars while a similar one fails. Frank William Bye, a miner who spent at least a decade in California’s gold fields, noted in 1852 that he “cleared over one hundred dollars per month.” This success did not allow him to forget that he was one of the few, as he follows by conceding that “hundreds of men equally as competent as myself [who] have been here all summer spend the last dollar” (BANC MSS 2014/58). An unidentified miner digging at the Yuba River in the Sacramento Valley perfectly describes how big the difference a short distance can be in his assessment of a claim located less than a mile from his where “there was a company of 20 men making 20 to $30 a day while all around there was many not making their board.” (BANC MSS 2015/3). What are now entrenched issues of economic disparity were already at play in the 1850s.

Rent and the cost of food in California are prime examples of too much demand for not enough land and supplies. Even though there were vastly fewer people in gold rush San Francisco than there are today, numerous letters marvel over the enormous sums asked for rent, which were far larger than anywhere else in the country. Architect Gordon Parker Cummings, whose contributions to California include San Francisco’s “Montgomery Block,” and Sacramento’s capitol building, complains to a friend in Pennsylvania that his two “3rd story rooms” in San Francisco rent for $900 a month, a cost that “would sound extravagant in Phill [but] it is a cheap one here” (BANC MSS 2014/35). The cost of basic foodstuffs also was drastically more expensive in California thanks especially to the difficulty of moving provisions from the port of San Francisco to the mines. In an 1853 letter to a friend, Charles Stone, a miner in Columbia, California (now a state park), notes at the beginning of the letter that flour costs $0.38 per pound, and by the end of the letter, written after a rainstorm, it was raised to $0.75 per pound (BANC MSS 2014/36).

Despite all of the unexpected hardships, California still held its charm for some newcomers who boasted of its “handsome buildings” and health benefits that were “worth all the Gold in California” (BANC MSS 2014/13; BANC MSS 2014/3). Even today, California is a beautiful place to live and generally has salubrious weather. So maybe there is more than one reason that millions continue to call it home.

– Louisa Brandt

Event: Bancroft Roundtable: Dangerous Ground: Squatters, Statesmen, and the Rupture of American Democracy, 1830-1860

The fourth and final Bancroft Library Roundtable of the spring semester will take place in the Lewis-Latimer Room of The Faculty Club at noon on Thursday, May 19. John Suval, Gunther Barth Fellow at The Bancroft Library and doctoral candidate in history at University of Wisconsin–Madison, will present “Dangerous Ground: Squatters, Statesmen, and the Rupture of American Democracy, 1830-1860.”

Squatters were a persistent frontier presence from the earliest days of the United States, yet these illegal settlers emerged as political and cultural lightning rods in the Jacksonian and antebellum periods. Why? This talk explores how squatters in the expanding West came to occupy a central place in U.S. political culture, territorial conquests, and conflicts leading up to the Civil War. California was a particularly violent and disruptive proving ground of squatter politics, and a primary focus of the discussion.

We hope to see you there. The talks are free and open to the public.

Kathi Neal

Bancroft Library Staff

Event: Bancroft Roundtable: Evidencing Boundaries: Text, Image, and Experience in Techialoyan Manuscripts

Please join us for the third Bancroft Library Roundtable of the spring semester.

It will take place in the Lewis-Latimer Room of The Faculty Club at noon on Thursday, April 21. Jessica Stair, Bancroft Library Summer Award recipient and doctoral candidate in History of Art at UC Berkeley, will present “Evidencing Boundaries: Text, Image, and Experience in Techialoyan Manuscripts.”

The textual-pictorial land titles known as the Techialoyans were created by indigenous authors during the later colonial period in Central Mexico in order to provide documentation of community land holdings to viceregal authorities. Written in Nahuatl and painted with depictions of figures and places, the Techialoyans are a subgenre of primordial titles that relies on images at a time when most manuscripts depended on alphabetic text. Surpassing mere illustrations, images play a crucial role in establishing authority in autochthonous claims to land. Ms. Stair examines multivalent roles of text and image, including their toponymic purposes, deictic functions, and references to lived experiences. She argues that the Techialoyans combine alphabetical text, images, and vestiges of indigenous oral traditions in order to embody the physical place of the land, as though one were walking through it. Linguistic features work with images to create a textual-pictorial-experiential nexus for establishing proof and shaping history.

We hope to see you there. The talks are free and open to the public.

Kathi Neal

Bancroft Library Staff

Event: Bancroft Roundtable: The Idle Readers of Piers Plowman in Print

The second Bancroft Library Roundtable of the spring semester will take place in the Lewis-Latimer Room of The Faculty Club at noon on Thursday, March 17. Spencer Strub, Bancroft Library Summer Award recipient and doctoral candidate in English and medieval studies at UC Berkeley, will present “The Idle Readers of Piers Plowman in Print.”

When the medieval English poem Piers Plowman was first printed in the sixteenth century, nearly two centuries after its composition, its readers were Protestant churchmen and scholars interested in mining a famously difficult work for its criticisms of Rome. Or so the story goes. A copy of the 1561 edition of Piers Plowman recently acquired by The Bancroft Library tells a rather different story. Its sixteenth- and seventeenth-century readers were laypeople, never attended university, and lived far from London and its intellectual circles. Over several decades, these modest provincial readers left copious notes and records in the book. Their marginalia include doodles, pen-trials, and jokes, but they also reveal readings that surprise with their inventiveness and insight. The focus of this talk will be on such “idle readers” of the Bancroft Piers and books like it–that is, on the readers who casually flipped the pages, marked their names, and drafted doggerel in the margins, rather than the scholars who read cover-to-cover with publication or career advancement in mind. Taking these idle readers seriously lets us better see the history of books and the afterlife of medieval poetry in the post-Reformation period.

We hope to see you there. The talks are free and open to the public.

Kathi Neal Bancroft Library Staff

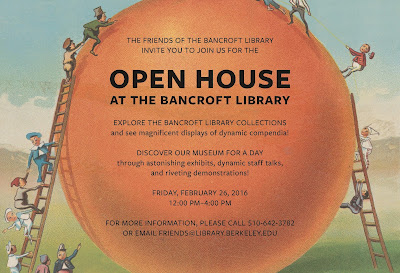

Event: The Bancroft Library’s Open House

Event: Bancroft Roundtable: “The Historical Background of the New Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.”

The first Bancroft Library Roundtable of spring semester will take place in the Lewis-Latimer Room of The Faculty Club at noon on Thursday, February 18. Ann Harlow, an independent scholar, will present “The Historical Background of the New Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.”

Ann Harlow will speak about the rocky road the University of California has been on in developing art museums from the 1870s to today. She will show images of the various buildings where art has been exhibited, as well as others that were imagined on paper but never built. Ms. Harlow is the former director of the art museum at Saint Mary’s College, author of an article on the beginnings of San Francisco’s art museums, and curator of the current exhibition at the Berkeley Historical Society, “Art Capital of the West”: Real and Imagined Art Museums and Galleries in Berkeley. She has used Bancroft resources for all of these projects as well as her book-in-progress, a dual biography of art patron Albert Bender and artist Anne Bremer.

The talks are free and open to the public.

Crystal Miles and Kathi Neal

Bancroft Library Staff

Event: Bancroft Roundtable: “Literary Industries: Hubert Howe Bancroft’s History Company and the Privatization of the Historical Profession on the Pacific Coast.”

Travis E. Ross, a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Utah, will present “Literary Industries: Hubert Howe Bancroft’s History Company and the Privatization of the Historical Profession on the Pacific Coast.” The event will take place in the Lewis-Latimer Room of The Faculty Club at noon on Thursday, November 19.

By the end of the nineteenth century, history writing was in the process of transitioning from a leisure activity for wealthy amateurs into a disciplined profession for a new class of academically trained historians whose research and publishing was underwritten by their university salaries. So the story goes. In the middle of that transitional period, between 1870 and 1890, the destination of professionalization remained uncertain. During that moment, a vertically integrated alternative to the modern historical profession dominated the Pacific Coast, eliciting surprising public support for a private monopoly over historical collecting, writing, and publication. This talk will reframe the professionalization of the historical enterprise by exploring the promise and the ultimate failure of the most (in)famous dead end along the road to our modern, academic profession.

Crystal Miles and Kathi Neal

Bancroft Library Staff

Event: Visualizing History: Mapping the 1915 San Francisco World’s Fair

Join Bancroft Library in celebrating the 100th anniversary of the 1915 San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exhibition by digitally mapping rarely seen photographs of the world’s fair onto a historic map of the fairgrounds using the Historypin platform.

The event will kick off with a gallery tour by Curator Theresa Salazar of the Bancroft Library’s PPIE exhibit: The Grandeur of a Great Labor: The Building of the Panama Canal and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, followed by a reception and brief talk in the beautiful Morrison Library.

Participants will then work together to explore archival images of the world’s fair and try to pinpoint the exact locations where the photos were taken. Using maps and guides as you would have 100 years ago, you’ll virtually find your way through “The Zone” and its sometimes-fatal carnival rides, wander through the massive exhibit halls, and marvel at the architecture of the state and country pavilions. History “pinners” will see their results live on the Historypin PPIE site at the event. We guarantee you’ll never see SF’s Marina neighborhood the same way again!

Thursday, November 19, 2015

4:00-4:30 pm – Location: Bancroft Library Gallery

Bancroft Library Gallery Tour with Curator Theresa Salazar – meet in the Bancroft Library lobby (following the gallery tour, participants will be escorted to the Morrison Library for the remainder of the event)

4:30-7:00 pm – Location: Morrison Library

Welcome Reception and Talk by Laura Ackley, author of San Francisco’s Jewel City: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915.

Demonstration and Pinathon

After a quick tour of the virtual fairgrounds, you’ll have a chance to get hands-on working in groups to help us pin historic images from Bancroft’s collections onto the 1915 fairground map, using clues, fair guides, maps, and more.

Live sharing on Historypin PPIE Site

We will have groups share some of the just-pinned materials Live on the Historypin PPIE site—Tell us what you discovered in your time travels!