In Episode 2, we explore Save Mount Diablo’s present. From supporting ballot measures and fundraising efforts to cultivating relationships with nature enthusiasts and artists to collaborating with outside partners, Save Mount Diablo continues to “punch above its weight.” This episode asks: now that Save Mount Diablo has conserved the land, how does it take care of it? How does Save Mount Diablo continue to build a community? How are artists activists, and how do they help support Save Mount Diablo? How does Save Mount Diablo sustain partnerships to conserve land?

In season 7 of The Berkeley Remix, a podcast of the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, we head to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County. In the three-part series, “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo,” we look at land conservation in the East Bay through the lens of Save Mount Diablo, a local grassroots organization. It’s been doing this work since December 1971—that’s fifty years. This season focuses on the organization’s past, present, and future. Join us as we celebrate this anniversary and the impact that Save Mount Diablo has had on land conservation in the Bay Area and beyond.

This season features interview clips from the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project. A special thanks to Save Mount Diablo for supporting this project!

LISTEN TO EPISODE 2 ON SOUNDCLOUD:

PODCAST SHOW NOTES:

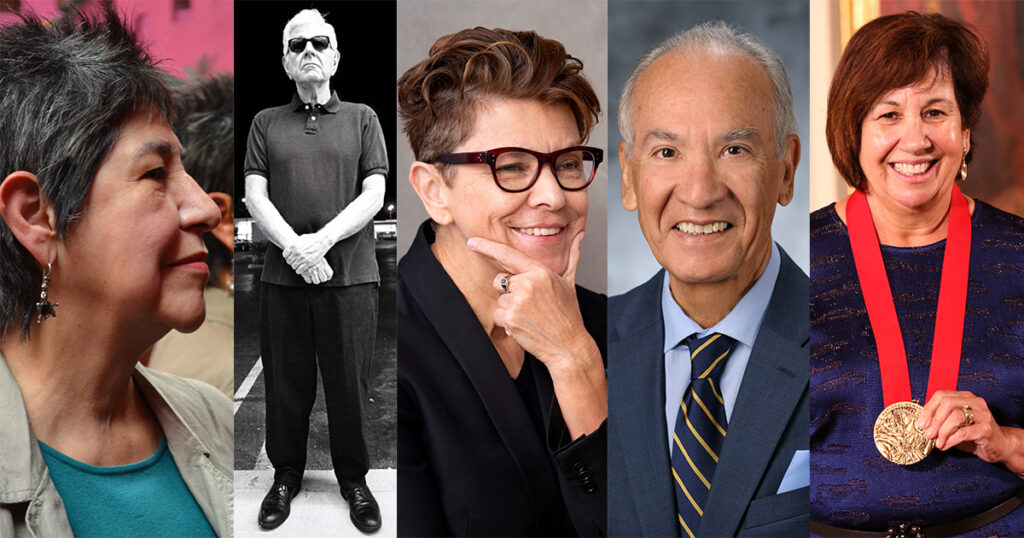

This episode features interviews from our Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project and includes clips from: Seth Adams, Bob Doyle, Ted Clement, Abby Fateman, Jim Felton, John Gallagher, Scott Hein, John Kiefer, Shirley Nootbaar, Malcolm Sproul, and Jeanne Thomas. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

This episode was produced by Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes, and edited by Shanna Farrell. Thanks to Andrew Deakin and Anjali George for production assistance.

Original music by Paul Burnett.

Album image North Peak from Clayton Ranch. Episode 2 image Lime Ridge Open Space. All photographs courtesy of Scott Hein. For more information about these images, visit Hein Natural History Photography.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT:

Amanda Tewes: EPISODE 2: Save Mount Diablo’s Present

[Theme music]

Shanna Farrell: Welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center at the University of California, Berkeley. You’re listening to our seventh season, “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo.”

Farrell: I’m Shanna Farrell.

Tewes: And I’m Amanda Tewes. We’re interviewers at the Center and the leads for the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project.

Tewes: This season we’re heading east of San Francisco to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County. In this three-part mini-series, we look at land conservation through the lens of Save Mount Diablo, a local grassroots organization.

Farrell: It’s been doing this work since December 1971—that’s fifty years. This season focuses on the organization’s past, present, and future. Join us as we celebrate this anniversary and the impact that Save Mount Diablo has had on land conservation in the Bay Area and beyond.

Farrell: In this episode, we explore Save Mount Diablo’s present.

Tewes: ACT 1: Now that Save Mount Diablo has conserved the land, how does it take care of it?

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Tewes: As we heard in our last episode, Save Mount Diablo was successful in accomplishing its original goal of expanding the Mount Diablo State Park from 6,788 acres to 20,000. It was also able to protect 90,000 acres of land that surrounded the mountain. These dreams were hard fought. Now that the organization had saved this land, how did it care for it? As we know, at first it relied on volunteers and supporters. Some of the volunteers who wanted to help beyond giving money found their way to different committees, like Stewardship and Land Acquisition.

Jim Felton: When I first started, we used to get together maybe four times a year, all the stewards, and talk about the problems and things that needed fixing. And of course, I’d go to a site that wasn’t mine to watch and help with the fence or help with some problem that needed fixing. Near Curry Canyon, there’s another property out there where the culvert got full of trees, and we all just had to climb in there and pull them out.

Farrell: That’s Jim Felton, who was a member of the Stewardship Committee before becoming president of Save Mount Diablo’s board. Each member of the Stewardship Committee is responsible for maintaining a parcel of land.

Felton: Well, it was once a month to check it out. So most of the time it was checking things out, but then there were jobs to do. We found bamboo or Arundo it’s called, Arundo in the creek in our property, and we wanted to get it out of there because it tends to spread, and it’s a very invasive species. So I spent quite a few hours digging and using a pick just getting that out of the river, and it hasn’t come back.

[Soundbed- river rushing]

Tewes: Some of the land hadn’t been maintained in some time, so it required a fair amount of cleanup. John Gallagher got involved with Save Mount Diablo in the year 2000. He started on the Land Committee and then moved to the Stewardship Committee. Here he is talking about the work he put in to care for neglected properties.

John Gallagher: I can’t tell you the number of trailers full of old car tires that we had hauled off, for example. Piles of pipe, barbed wire, and so forth that we’ve hauled off to the recycle center or whatever.

[Soundbed- construction, truck hauling garbage]

Farrell: There was no cost to being involved with Save Mount Diablo in this way. Jim Felton remembers it was just “gas and time.”

Felton: For old guys, it was pretty messy projects, but no, no cost but just gas, but time, really, and a sore back.

Tewes: But there was joy in this hard work. John Gallagher says:

Gallagher: And of course it’s all outdoors. You know, we get to go places where other people don’t get to go, and I like that.

Farrell: As Save Mount Diablo moved beyond its original function as an advocate for land conservation, it realized it needed to build relationships with people who owned property near its land parcels. Here’s land conservation director Seth Adams.

Seth Adams: Well, the unusual thing about Save Mount Diablo is that we started as an advocacy organization and then added acquisition functions.

[Soundbed- door knocking]

Adams: If we buy a piece of property, we’re going to be in contact with the neighbors, and more likely than not, we’re going to protect land next door to that property because they get to know us, and they see that we’re upfront and responsible and do what we say we’re going to do and we’re nice and we’re not confrontational. And buying a property is always a gateway to the surrounding properties.

Tewes: These relationships mattered, especially when it came to land acquisition. Here’s board member and former president Scott Hein.

Scott Hein: The idea is to try to develop relationships with long-time landowners who may have property that you would like to acquire at some time, so that when they’re ready to sell they’ll think about you. You know, they might not give you a bargain, but at least they won’t be opposed to thinking about doing a deal with you, and so that’s the sort of general idea. And so it takes developing relationships and maintaining those relationships over time and communicating. It’s something you have to be proactive about. The landowners aren’t going to come and find you; in most cases, you have to go find them, and then figure out what kind of relationship they want to have.

Adams: When a landowner is going to sell their property, they typically want the highest value. There are some that are really enlightened, and they have come to you because they want to see their properties protected, and that’s growing, but it wasn’t the norm in the early years. There’s a lot of land-rich, cash-poor landowners around Mount Diablo.

Farrell: That was Seth again. The organization has to prioritize which properties it wants to acquire. Here’s Seth talking about how to consider those decisions.

Adams: Let’s say we know that our priority list has 180 properties on it, and we have a Landowner Outreach Subcommittee that meets monthly, and we go over to the top twenty of those priorities.

Tewes: The volunteers in the Land Committee still play a big role in acquiring land. Here’s John Gallagher again.

Gallagher: We keep a list about that and then try to decide if the cost of the property is worth it. Just as you and I might decide to buy a new couch or something like that, you just have to make that calculation. Well, I really like it, but is it worth it, do I need it that badly? And the Land Committee makes those decisions and recommendations. “Hey, listen, there’s a nice piece of property, but it’s totally surrounded by houses, and even though it adjoins a state park, it will never be a place for access or anything else, it would just be another parcel. If it’s really cheap, let’s go for it.” Or we say, “We need this one, this is something we’ve looked at, it’s been on our list for twenty-five years.”

Farrell: Here’s Seth again.

Adams: And then you wait for those times in people’s lives when they either put it up on the market or you know something is going to happen. This landowner’s husband died and so that’s a life change, which probably is going to result in opportunity. It’s the four D’s: death, divorce, disaster, disease, [laughs] and those are the times when conservation is most likely to happen.

Farrell: Jim Felton also explains that building relationships with neighbors is part of Save Mount Diablo’s stewardship model.

Felton: We’ve had events for neighbors, some of our sites, and barbecues and things. And some people really like Save Mount Diablo in the neighborhood and some people just don’t like them at all, and they were really nasty. It’s too bad because, I mean, what we’re doing is preventing somebody from building ten houses next door to them, but they didn’t like it. They saw it almost as government intrusion, that type of behavior.

Tewes: The organization knows how to strike when the iron is hot. In the late 2000s, during the recession, it saw an opportunity. John Gallagher remembers:

Gallagher: We didn’t have very many properties anyway, and then during the recession, we acquired a whole bunch of them, bang, bang, bang, bang. And they were often distressed properties that had junk on them or gates that didn’t work or fire abatement that wasn’t being done.

Farrell: Save Mount Diablo doesn’t just acquire new lands, it supports political action as a way to conserve open space. This means it also backs local ballot measures that limit growth of new development in Contra Costa County. Here’s Scott Hein.

Hein: Prior to the establishment of the urban limit line, there was a lot of speculative development going on around the County in all the cities in the County, and it was really difficult for Save Mount Diablo or anyone interested in protecting that land to get their hand around it.

[Soundbed- construction]

Tewes: Urban limit lines are important. They stop development from happening, which can in turn, protect plants and animals.

[Soundbed- bird noises]

Tewes: In 1990, County voters approved Measure C, the 65/35 Ordinance, which required at least 65 percent of land be preserved for agriculture, parks, and other open space. In 2006, Contra Costa County residents voted to extend this limit for up to another 30 years.

Farrell: As Save Mount Diablo got more involved with local politics, it became more visible. As a result, it drew more people to the organization.

[Theme music]

Farrell: ACT 2: How did Save Mount Diablo continue to build a community?

John Kiefer: I love the mountain, but in reality, it’s more accurate to say I love the people that love the mountain.

Tewes: That’s longtime Save Mount Diablo supporter John Kiefer. It takes a whole community to rally around the organization, and this includes those with varying interests in the natural space. One group that loves the mountain include those who support wildlife like falcons.

[Soundbed- peregrine falcons]

Farrell: The chemical DDT had been a commonly-used insecticide since the 1940s. It was sprayed all over, mainly to kill mosquitoes. But DDT caused a lot of damage, including around Mount Diablo. It destroyed bird populations because it thinned the eggshells of baby birds like peregrine falcons, killing them before they could hatch. By 1950, peregrines had disappeared from Mount Diablo. And in 1970, they were listed as an endangered species in California. DDT was nationally banned in 1972 after the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson brought its dangers to light. That same year, there were only 2 nesting pairs of peregrine falcons left in the entire state of California.

[Soundbed- sad sounds of birds]

Tewes: Over a decade later, in 1989, peregrine falcons were reintroduced to Mount Diablo by wildlife biologist Gary A. Beeman. Seth Adams and Save Mount Diablo played a key role in this work by gathering volunteer supporters and helping to fund it. Here’s Shirley Nootbaar, who lives near the mountain and loves peregrines.

Shirley Nootbaar: [laughs] The Peregrines, you know, were first started back on the mountain back in the end of the eighties. They tried to encourage nesting. They would have prairie falcons incubate the vital eggs of peregrines that they had produced in probably zoos, and that was the way they finally got the wild peregrines to start in Pine Canyon, which is right near where I live.

Farrell: These falcons have an ardent group of supporters, including the Peregrine Team in Pine Canyon, which was founded in 2015. This is a natural history group that assists park rangers during nesting season. Thanks to its efforts, there are now about 400 pairs of peregrine falcons in California, which matches estimates from pre-DDT levels. Shirley is actively involved with this group.

Nootbaar: Last year, they did not produce any chicks. This year, they did, and it was exciting. The Peregrine Team was overjoyed. The pair of peregrines had four eggs that blossomed into chicks, and everybody was so excited, but a great horned owl came along and ate them.

[Soundbed- peregrine falcons]

Malcolm Sproul: Everybody loves peregrine falcons; you know, it’s a sexy, you know, dynamic bird.

Tewes: That was Malcolm Sproul, who works in environmental planning. He was also Save Mount Diablo’s board president when the organization started to participate in BioBlitz. BioBlitz is a day-long event where naturalists and citizen scientists inventory all species of plants and animals living in a designated area. Malcolm plays a big role in Save Mount Diablo’s BioBlitz.

Sproul: I’m a participant, a very willing participant. You go out to an identified area, and you’re trying to document as many species as you possibly can in a twenty-four-hour period. And my expertise is birds and mammals, you know, a little bit of plants. If I see something interesting, I can record it and tell people. But primarily, I’m out there because of wildlife, and it’s just fun to get out in the field. And it’s a chance to get together with other people with similar backgrounds and interests, and share that. Then the organization loves to use it as a way to say how valuable properties are.

[Soundbed- birds and frogs]

Farrell: During BioBlitz, the group often identifies over 700 species that live in the Diablo Range.

Sproul: To me, that’s the real value of it. It’s when you find something that you didn’t know was there, and you can find maybe why it’s there, but that’s a little piece of information that we didn’t have before.

Tewes: BioBlitz brings new people to the mountain. They also act as a gateway to another Save Mount Diablo educational event: Four Days Diablo. Here’s Scott Hein talking about this.

[Soundbed- gravel crunching, people walking through dirt]

Hein: So it’s, you know, thirty to forty miles, depending on the side trips we take. Three nights we hike entirely on public lands the whole way, except for in more recent years we’ve detoured onto our Curry Canyon Ranch Property, and we get permission to hike out through a private ranch on that day. You can hike from Walnut Creek to Brentwood and immerse people in the work that we and our partners have done for, you know, the last fifty years. There’s no better way to expose people to the work we do and the importance than getting them out on the land.

Tewes: John Gallagher says:

Gallagher: At the time, Seth was leading every hike, so he was able to brag and brag and brag about what Save Mount Diablo had done with this property and that property.

Sproul: We take people out for four days. They get spoiled—I mean, they have to hike. It’s hot sun and things like that, and you get blisters, and some people can’t make it. It’s some work. But it’s taking people out into the areas that have been protected, and showing them what they have helped protect.

Tewes: That was Malcolm Sproul.

[Soundbed- people walking]

Farrell: Indeed, this event also helps develop relationships with potential donors. Another event that brings these donors back to the land is Moonlight on the Mountain. This fundraising dinner every September takes place at an area called China Wall. And it takes effort to get out there.

Felton: So it’s on a flat mesa area on this ridge right next to what’s called China Wall, which is a geological formation that’s pretty unique, a lot of just outcroppings. We’d light that up with spotlights, so as the sun goes down, it is all beautifully lit, and the visuals are really amazing. And of course some years, you get the moon, some years, it doesn’t always work out that way.

Tewes: That’s Jim Felton. Here’s Scott Hein again.

Hein: So the idea with Moonlight on the Mountain is: bring 500 of our closest friends up onto the mountain and have a white tablecloth sit-down dinner, sitting outside, not under tents or anything like that, and have an evening of, you know, learning about the organization and making contributions and bidding on artwork and experiences and things like that. So it’s completely unique, right? I don’t know of any other events like it in the Bay Area, where you bring that many people outside in the environment, sitting in front of the mountain.

Tewes: This is a beloved event. It draws volunteer support from many. For instance, John Gallagher helps set up for the event. The night before, he sleeps in his truck on the mountain.

Gallagher: Once in a while, the cows will come around and stick their nose in my nose while I’m asleep, you know, in the bed of my truck.

[Soundbed- cow noise]

Gallagher: [laughs] And of course I hear the coyotes calling, which is always a delight. But you know, the wind comes up and the fog comes in or something like that, and it’s just nice and quiet and serene.

Farrell: While some of these events bring in money, they all build community around Save Mount Diablo. Another way the organization does this is through educational efforts. If you don’t know about the land, you can’t love it enough to preserve it. Here’s executive director Ted Clement talking about the program on Mangini Ranch Educational Preserve, where community groups and schools can explore the land.

Ted Clement: I started to hear more and more from teachers that were doing our Conservation Collaboration Agreement Program that it was powerful for the students. And they really liked that students were out on our properties having these intimate experiences in nature and there was no one else there, not like a state park with lots of outsiders and other people wandering around. The teachers said it just felt very safe and intimate. And we want to make it as easy as possible and as affordable as possible for all these different groups of people to get out there and have a really special, intimate experience in nature. It’s their property for the day.

[Theme music]

Tewes: ACT 3: How are artists activists, and how do they help support Save Mount Diablo?

[Soundbed- river flowing]

Tewes: Mount Diablo is a beautiful place, with its sprawling vistas and rolling hills, where grasslands give way to wooded areas. It’s been a source of inspiration over the years for many artists. And Save Mount Diablo has been lucky to attract a community of these artists, like Shirley Nootbaar, Scott Hein, Stephen Joseph, and Bob Walker, who care about the mountain enough to capture it in their paintings and photographs.

[Soundbed- camera clicking]

Tewes: These pieces illustrate the beauty of the range, and why it’s worth preserving.

Farrell: Shirley Nootbaar, who lives in Walnut Creek, started painting the mountain in the 1970s. She sees the landscape through an artist’s eyes.

Nootbaar: The trees are a rich green and right now the grasses are golden and the sky is blue, I mean those colors, green, kind of a raw umber or raw sienna kind of color, and the beautiful blue of the sky. So as far as the colors of painting the mountain, it kind of depends on what your mood or your idea at the time is, and it changes all the time.

Tewes: Shirley taught watercolor classes and brought her students to the mountain to paint what they saw. She also got involved with the Mount Diablo Interpretive Association.

Nootbaar: In 1983, I think it was, they were able to open up the museum at the top of the mountain after it was closed for a number of years. We formed an art committee through the Mount Diablo Interpretive Association, and the art committee created these various shows, probably four times a year, and hung work of the various people that would submit work, and it was different themes of either a particular area or maybe it was a high school group or whatever; could be photography, as well, of course. Yeah, I thought it was very successful.

Farrell: Photographs are also an important part of Save Mount Diablo’s advocacy. Scott Hein is a nature photographer and takes photos for the organization. Seth Adams even sends him out on assignment to photograph land around the mountain.

[Soundbed- more camera clicking]

Hein: Not all the lands we protect are easily accessible, and not every person has the time or the ability to get out on the land, and so photographs are the next best thing. They’re the way that we can communicate that beauty to people who can’t experience it in person, and conservation photography has been a critical tool going almost all the way back to the beginning of land conservation.

Tewes: Scott’s work has many admirers, like Shirley.

Nootbaar: Scott Hein in the Save Mount Diablo organization does a beautiful job with photographs.

Farrell: Before Scott was Bob Walker. Remember him from episode one?

Hein: Bob Walker was involved with the organization and doing nature photography and conservation photography from 1982 to 1992, when he passed away. He was a real environmental advocate, who was also a fantastic photographer. He was just relentless in photographing, and taking people out there to hike and learn about it.

Jeanne Thomas: His photography told a story. And the mountain, you looked down and could see development coming up and say, “Oh, if it weren’t for the park, the development wouldn’t stop.”

Tewes: That’s longtime volunteer and donor Jeanne Thomas. She also loves to take photographs on the mountain, including of local wildflowers. There’s a strong connection between Mount Diablo and these artists. Here’s Shirley Nootbaar again, talking about what the land has meant to her.

[Soundbed- bird and animal noises]

Nootbaar: I love where I live, I love to hear the birds, and I love the animals, and when I go up into the park, I’m always aware of that. I’m not a botanist, I’m not a biologist, I’m not a zoologist, I’m not a geologist, but I do appreciate all of those things. It’s much my therapy and my love.

[Theme music]

Farrell: ACT 4: How does Save Mount Diablo sustain partnerships to conserve land?

Farrell: From the beginning, Save Mount Diablo has been an organization that’s worked collaboratively with outside partners. This has become an even more important part of its model. The organization works with the California State Park system, as Mount Diablo is a state park. It also collaborates with the East Bay Regional Park District and the East Contra Costa Habitat Conservancy to accomplish its goals.

Tewes: In 1988, Save Mount Diablo original member Bob Doyle started working for the East Bay Regional Park District. Though he was working for the Park District, which was founded in 1934, he never forgot about his roots with Save Mount Diablo. Bob and Seth Adams worked together to pass a local bond measure that would provide funding to both entities. Here’s Bob discussing the impact of that measure and the longevity of that relationship.

Bob Doyle: As the state got less and less money for expanding the state park system, the Park District was getting more. In 1988 was the big change, and Bob Walker and along with Seth and everybody else, really worked to pass the first bond measure in the history of the Park District, and I co-wrote it and wrote the acquisition section. And you don’t invent it, you create it with people who are going to fight for it. And so I made sure that there were money for those regional parks surrounding Mount Diablo and for new ones. And I think we need every environmental group, every land trust to be walking in the same direction to get more money not just for their cause, but for everybody’s cause, which is called saving this planet.

[Soundbed- nature and animal noises]

Farrell: Another of Save Mount Diablo’s significant partners is the East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservancy. The Conservancy was formed in 2007 and grew out of the Habitat Conservation Plan, or the HCP. Planning for the HCP began in the late 1990s. It was written as a way to satisfy the federal Endangered Species Act, with a lot of help from John Kopchik, director of conservation and development for Contra Costa County.

Tewes: The nuanced goals of the HCP are to protect open space, enhance over 30,000 acres of habitats and natural systems, and to streamline wetland and regulatory compliance. The Conservancy was formed to help make these goals a reality. The way it accomplishes these goals is by buying, restoring, and protecting large parcels of land in East Contra Costa County that are home to hotspots for biodiversity. It issues permits for the land it owns and reinvests the money in buying even more land to protect. Often, the Conservancy will buy land in the Diablo Range and work with Save Mount Diablo to manage and preserve it.

Farrell: Abby Fateman, who is now the executive director of the Conservancy, works closely with Save Mount Diablo. She was hired by John Kopchik in 2002 to help with the next steps of writing the HCP and forming the Conservancy. Here she is talking about how instrumental John Kopchik was in forming those partnerships.

Abby Fateman: I think one of the reasons why the HCP worked or was adopted was really because he was able to build trust with all these different groups. He had relationships with the private landowners, with the developers, with Save Mount Diablo and other groups, and they were genuine.

Tewes: One of the ways that Save Mount Diablo and the Conservancy work together is by looking at maps and assessing which parcels of land are most critical to preserve. They start small and build from that foundation.

Fateman: We like to bite things off in smaller pieces and understand them and work on them and then that’s an achievable goal. And then when that’s sort of handled, then we can expand our understanding of our goals. And “Save Mount Diablo” as a slogan was something that people could relate to. They could see the mountain, they could see development, they could see people trying to develop on the mountain, and they could rally around that.

Farrell: The partnership between Save Mount Diablo, the East Bay Regional Park District, and the Conservancy is crucial. All three entities bring different strengths to the table to accomplish a common goal.

Fateman: Properties become available once a generation, and if somebody wants to sell it to you, if you have a willing seller or you’re able to compete for it, then you should go for it. Save Mount Diablo plays a huge role in actually executing on those things, making land acquisition happen, as does the East Bay Regional Park District. And they move very differently. You know, Save Mount Diablo is a nonprofit organization that can move very quickly and they’re much more nimble than my agency or East Bay Regional Park District. We might have more money available in the longer term, but we can’t show up at a land auction and bid on something. We can’t, there’s no way that that could happen, but Save Mount Diablo can.

Tewes: These strengths benefit all three partners, though sometimes with differing points of view.

Fateman: Save Mount Diablo fights certain development projects that they think are bad, and just because we have an HCP and just because they are our stakeholder doesn’t mean that they don’t fight those. We still provide permits for projects that they don’t agree with, and that’s okay, they don’t give that up, there are people fighting that fight. What we’re saying is we’re removing this one place, which is in compliance with the Endangered Species Act and how people mitigate for that from that battle.

Farrell: Here’s Bob Doyle again, talking about it from the Park District’s perspective.

Doyle: Even though I was in charge of the Land Acquisition Program for the District, and it had money at that time, there were things that I just couldn’t do as the manager or the public agency side. Save Mount Diablo and Greenbelt Alliance and People for Open Space were all doing those things. The landowners always accused us of a grand conspiracy, and to some degree, there was an effort to work together, absolutely, to preserve as much property as possible.

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Tewes: The partnership between these three entities benefit the cause of land conservation in Contra Costa County.

Doyle: You can’t do these things, no matter how great the effort is and the talent is in an institution, without activism and public support.

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Fateman: We have a successful, active, engaged nonprofit like Save Mount Diablo that is well funded and positioned; and we have this larger, regional agency, East Bay Regional Park District; and then the Habitat Conservancy. And I think we have managed to be able to work together in a way where we really thrive on each other’s strengths. You know, we don’t coordinate on every single action or movement we make, but we know when we can tap each other’s superpower and use it, and I think that separates us from other regions, it really does. And that’s why we see so much conservation happening in Contra Costa County versus other regions is that we sort of have it dialed in. It’s not perfect, but it’s way better than not having each other to work with.

Doyle: That collaboration is the only way that we can take on such a difficult, difficult task politically and economically of climate change.

Fateman: We haven’t finished that goal of saving the mountain, but gosh, we’re so much closer than we were fifty years ago when all this started. It’s kind of amazing.

Tewes: Save Mount Diablo also appreciates these relationships. Here’s executive director Ted Clement thinking about the importance of working in teams, even within the organization.

Clement: Ultimately, good land conservation is good teamwork, and it’s only going to last long term if it is about a team, and a strong team that can carry the work on going forward.

Farrell: Join us next time as we learn about the future of Save Mount Diablo.

[Theme music]

Farrell: Thanks for listening to “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo” and The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1953, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world. This episode was produced by Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes.

Tewes: This episode features interviews from our Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project and includes clips from: Seth Adams, Bob Doyle, Ted Clement, Abby Fateman, Jim Felton, John Gallagher, Scott Hein, John Kiefer, Shirley Nootbaar, Malcolm Sproul, and Jeanne Thomas. A special thanks to Save Mount Diablo for supporting this project. Thank you to Andrew Deakin and Anjali George for production assistance. To learn more about these interviews, visit our website listed in the show notes. Thanks for listening and join us next time!