Tag: primary sources

Primary Sources: The Atlantic Magazine Archive

Through the California Digital Library, the Library has access to the Atlantic Magazine Archive that includes the years 1857-2014.

Through the California Digital Library, the Library has access to the Atlantic Magazine Archive that includes the years 1857-2014.

The Atlantic was originally created with a focus on publishing leading writers’ commentary on abolition, education and other major issues in contemporary political affairs at the time. Over its more than 150 years of publication it has featured articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, science and more.

Some of the founding sponsors of the magazine include prominent writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Greenleaf Whittier.

Primary Sources: International Herald Tribune Archive, 1887-2013

The Library now has access to the The International Herald Tribune Historical Archive (1887-2013), which features the complete run of the International Herald Tribune from its origins as the European Edition of The New York Herald and later the European Edition of the New York Herald Tribune. The archive ends with the last issue of the International Herald Tribune before its relaunch as the International New York Times.

Primary Sources: Women’s Studies Archive

Through the California Digital Library, our Library has access to three modules of Gale’s Women’s Studies Archive.

Women’s Studies Archive: Women’s Issues and Identities provides the opportunity to witness history from the female perspective. Offering coverage of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the digital archive allows for the serendipitous discovery of commonalities among a variety of archival collections. Global in scope, it presents materials covering the social, political, and professional aspects of women’s lives and offers a look at the roles, experiences, and achievements of women in society. A wide range of primary sources provide a close look at some of the pioneers of women’s history, a deep dive into the issues that have affected women, and the many contributions they have made to society. Within the archive can be found historical records from Europe, North and South America, Africa, India, East Asia, and the Pacific Rim with content in English, French, German, and Dutch.

Women’s Studies Archive: Women’s Issues and Identities provides the opportunity to witness history from the female perspective. Offering coverage of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the digital archive allows for the serendipitous discovery of commonalities among a variety of archival collections. Global in scope, it presents materials covering the social, political, and professional aspects of women’s lives and offers a look at the roles, experiences, and achievements of women in society. A wide range of primary sources provide a close look at some of the pioneers of women’s history, a deep dive into the issues that have affected women, and the many contributions they have made to society. Within the archive can be found historical records from Europe, North and South America, Africa, India, East Asia, and the Pacific Rim with content in English, French, German, and Dutch.

Women’s Studies Archive: Voice and Vision explores critical areas of study including the abolition of slavery, alcohol and temperance movements, pacifism and political activism, domestic service, education, health and hygiene, divorce and social reform, and much more. A vast range of primary sources from 1780 to 2000 span multiple geographic regions, providing an abundance of perspectives on women’s experiences and impact on society around the world.

Women’s Studies Archive: Voice and Vision explores critical areas of study including the abolition of slavery, alcohol and temperance movements, pacifism and political activism, domestic service, education, health and hygiene, divorce and social reform, and much more. A vast range of primary sources from 1780 to 2000 span multiple geographic regions, providing an abundance of perspectives on women’s experiences and impact on society around the world.

Women’s Studies Archive: Rare Titles from the American Antiquarian Society (1820-1922) covers the nineteenth and twentieth centuries across multiple disciplines, including literature studies, women’s history, gender studies, cultural studies, critical theory analysis, American history, media and journalism, politics, and sociology.

Women’s Studies Archive: Rare Titles from the American Antiquarian Society (1820-1922) covers the nineteenth and twentieth centuries across multiple disciplines, including literature studies, women’s history, gender studies, cultural studies, critical theory analysis, American history, media and journalism, politics, and sociology.

Primary Sources: China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology, & Literary Publications

China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology, and Literary Periodicals, 1817–1949 is a collection of seventeen English-language periodicals published in or about China during a period of over 130 years extending from 1817 until 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was founded. This corresponds to the periods of the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican Era (1911-1949), when China experienced radical and often traumatic transformations from an inward-looking imperial dynasty into a globally engaged republic with modern approaches to politics, literature, education, public morality, and intellectual life.

China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology, and Literary Periodicals, 1817–1949 is a collection of seventeen English-language periodicals published in or about China during a period of over 130 years extending from 1817 until 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was founded. This corresponds to the periods of the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican Era (1911-1949), when China experienced radical and often traumatic transformations from an inward-looking imperial dynasty into a globally engaged republic with modern approaches to politics, literature, education, public morality, and intellectual life.

Periodicals included in the collection:

- The Chinese Recorder (教務雜誌, 1867–1941) was produced by the Protestant missionary community in China that enjoyed a run of 72 years, longer than any other English-language publication in that country. The complete set of the journal, along with its predecessor, the Missionary Recorder, is available in this collection. The journal is regarded today as one of the most valuable sources for studying the missionary movement in China and its influence on Western relations with and perceptions of the Far East.

- West China Missionary News (華西教會新聞, 1899–1943) was established and published in Sichuan, China by the West China Missionary News Publication Committee. The journal aimed to enhance communication among missionaries based in western China and published many articles on the missionary activities in the region.

- The China Mission / Christian Year Book (中國基督教年鑑, 1910–1939) was published under an arrangement between the Christian Literature Society for China and the National Christian Council of China. It started in 1910 as The China Mission Year Book and changed its title to The China Christian Year Book in 1926. This digital version also includes The China Mission Hand-book (1896) and A Century of Protestant Missions in China (1807–1907).

- Educational Review: continuing the monthly bulletin of the Educational Association of China (教育季報, 1907–1938) was the official journal of the Educational Association of China which later changed its name to China Christian Educational Association. Founded in Shanghai in 1907, it was published first as a monthly during 1907–1912 and then as a quarterly during 1913–1938. The journal publishes minutes of the meetings of the Association and reports of affiliated local associations. There were also articles covering Christian colleges and universities founded across China.

- The Canton Miscellany (廣州雜誌, 1831) was a literary journal published in Guangzhou (Canton) between May and December 1831. Anonymously edited, it targets the well-educated English elite. The last two issues contain lengthy articles on the history of Macau, the first ever to be written in English.

- Chinese Miscellany (中國雜誌, 1845–1850) was founded by Walter Henry Medhurst (1796–1857), an English Congregationalist missionary to China. The journal consists of four volumes, introducing China’s silk and tea industry, geography, manufacturing, trade, and customs.

- The Chinese and Japanese Repository of Facts and Events in Science, History, and Art, Relating to Eastern Asia (中日叢報, 1863–1865) was edited by James Summers (1828–1891), a professor of Chinese language of the University of London. The journal documents China and Japan’s often violent reactions to the presence of foreigners from a Western perspective.

- Notes and Queries: on China and Japan (中日釋疑, 1867–1869) was one of the earliest sinology journals. Edited by Nicholas Belfield Dennys (1840–1900) and published in Hong Kong, it focuses on topics such as Chinese history and culture. Japan and Korea are also covered.

- The China Review: or Notes and Queries on the Far East (中國評論, 1872–1901) was arguably the first major Western sinology journal; many of the renowned sinologists of the nineteenth century contributed articles, including James Legge, Herbert A. Giles, Joseph Edkins, John Chalmers, Ernst Faber, Edward L. Oxenham, W. F. Mayers, Alexander Wylie, Edward Harper Parker, and Frederic Henry Balfour.

- The New China Review (新中國評論, 1919–1922) was established by British sinologist Samuel Couling in Shanghai in 1919, aiming to inherit the mantle of The China Review, which was discontinued in 1901. Contributors to its four volumes include such prominent sinologists as Herbert A. Giles and Edward H. Parker.

- The Indo-Chinese Gleaner (印中搜聞, 1817–1822) was a quarterly journal founded by Robert Morrison (1782–1834) and William Milne (1785–1822) in Malacca in 1817. This periodical covered missionary activities, reported on the social, political, religious, military, economic, and cultural affairs of China and other Asian countries, and introduced the literature, philosophy, and history of Asian countries, especially those of China and Southeast Asia.

- Bulletin of the Catholic University of Peking (輔仁英文學志, 1926–1934) was founded in September 1926 and published a total of nine volumes. Each volume contains articles on the university’s developments and achievements, as well as sections devoted to the study of Chinese culture. It ceased publication in November 1934 and gave way to a purely academic journal titled Monumenta Serica.

- The Yenching Journal of Social Studies (燕京社會學界, 1938–1950) was founded in June 1938 and published semi-annually. This journal, which ceased publication in 1950 after releasing the first part of Volume five, provides significant research materials on the history of social studies in China during the Republican period (1911–1949).

- The China Quarterly (英文中國季刊, 1935–1941), founded and run jointly by the China Institute of International Relations, the Pan-Pacific Association of China, and the Institute of Social and Economic Research, was an authoritative journal discussing topics on China’s internal and external affairs. The journal had a stellar editorial and contributor team, including such prominent scholars as Tsai Yuan-pei (蔡元培), Chungshu Kwei (桂中樞), Wu Lien-teh (伍連德), John Benjamin Powell, Hollington Tong (董顕光), and Lin Yu-tang (林語堂).

- T’ien Hsia Monthly (天下月刊, 1935–1941) was published under the auspices of the Sun Yat-sen Institute for the Advancement of Culture and Education. Editors included John C. H. Wu, Wen Yuan-ning, Lin Yu-tang, and others. This cultural and literary journal was dedicated to introducing and interpreting Chinese literature and art for the West and promoting understanding between East and West.

- The China Critic (中國評論週報, 1928–1946) was a weekly founded on 31 May 1928 by a group of Chinese intellectuals who had studied in the United States. Despite the editors’ avowed preference for “nonpolitical” discourse, The Critic’s editorials and articles frequently discussed the presence of imperialism in Shanghai, debated the abolition of extraterritoriality, and advocated equal access to public facilities in the concessions. The editors also participated in wider-ranging discussions about urban affairs.

- The China Year Book (中華年鑑, 1912–1939) was edited by British journalist and publisher H.G.W. Woodhead (1883–1959) with H.T.M. Bell to provide information on China for Westerners. It was published from 1912 to 1939, incorporating documents related to each year’s events in China. Woodhead was the editor of the Peking and Tientsin Times from 1914 to 1930 before moving to Shanghai to write for the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury and later edit his own journal, Oriental Affairs.

Primary Sources: Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movements

The Library has invested in the creation of Reveal Digital’s Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movement and now has access to the first batch of digitized content on the JSTOR platform. The following information about the collection was shared in Reveal Digital’s announcement:

Covering primarily the 1950s and 1960s, Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movements provides access to primary source documents that focus on how ordinary citizens in the smaller communities viewed, participated in and lived through this historical era. When completed in 2025, the collection will include letters, general correspondence, logs, demonstration plan outlines, transportation logs and plans, meetings, worship services, photographs, newsletters, news reels, interviews and musical recordings from Black, Latine, Native American and Asian American Pacific Islander communities.

The eight compilations from the Atlanta History Center include:

- Alert Americans Association broadside “Martin Luther King…At Communist Training School”

- Atlanta American Council of Christian Churches documents on the Black Manifesto

- Clarence Bacote papers

- Coretta Scott King documents

- Herman L. Turner papers

- Jones family papers of Lovett School

- Roland M. Frye papers

- Southern Regional Council documents

A link to this collection can be found in the History: America guide under Parimary Sources by Topic > Civil Rights and in the Library’s A-Z Database list.

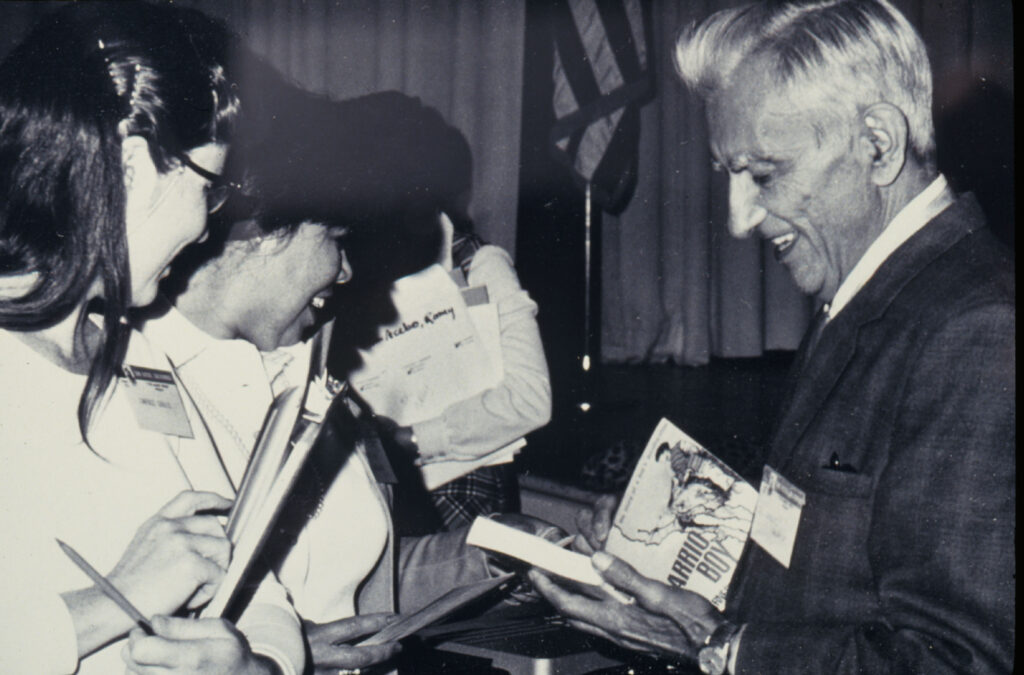

A spearhead for the barrio: the educational activism of Ernesto Galarza

From the Archives

By Adam Hagen

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center houses a number of oral histories that center the lives of Mexican American activists. One such history, Burning Light: Action and Organizing in the Mexican Community in California, contains the recorded speeches and interviews of Ernesto Galarza from the late 1950s through the early 1980s, and provides a glimpse into the life of a man whose commitment to the Mexican American agricultural workers of California never wavered, even when he found himself a continent apart from them.

Galarza’s words, which he imbues with a certain dry poetry, recount a life of extraordinary experience and achievement: Galarza worked as an organizer with the United Farm Workers of America, where he was instrumental in bringing the bracero program to an end; as an educator at the elementary and collegiate levels; and for a time as the chairman of the development of bilingual educational material for the National Committee of Classroom Teachers. He also worked as a consultant for several organizations and institutions, including the government of Bolivia. A recurring theme in Galarza’s oral history, and the subject of this profile, is his efforts on behalf of bilingual education and Spanish literacy advancement in the Mexican American community.

Galarza was born in the village of Jalcocotán in the Mexican state of Nayarit in 1905. But fleeing the tumult of Francisco Madero’s revolution, he and his family came to Sacramento in 1911, when the Central Valley’s patchwork of farm property was not yet its present expanse and its limits did not so easily elude the eye. There, enveloped in a community of agricultural laborers in the Sacramento barrio, a young Galarza would see firsthand the struggles of Mexican Americans and braceros as they tried to navigate the foreign land in which they now found themselves. And, as his family was of modest means—exacerbated by his mother’s death in 1917—he too joined in this work from an early age. One of the recorded talks compiled in the oral history contains a poignant allusion to his communities’ challenges in adapting to life in the United States, and, as it deals with the matter of English language acquisition, reveals the seeds of his future work. In the talk, Galarza recalls that he “became a leader in the Mexican community at the age of eight for the simple reason that I knew perhaps two dozen words of English.”

English proficiency, however, was only one of a number of skills that Galarza exhibited in his youth. His academic prowess was so apparent that Sacramento High School teacher Ralph Everett approached him personally and asked that he reconsider his plan to work at the Sacramento Libby, McNeill & Libby cannery after graduation, insisting that he attend college instead. Everett even went to great lengths to help Galarza gain admission to Occidental College in Los Angeles, the institution he would graduate from in 1927. After Occidental, Galarza would go on to earn a master’s degree in history from Stanford University in 1929 and a doctorate in sociology from Columbia University in 1944.

Galarza’s recollection of his time at these institutions reveals how rare it was for a “Mexicano” to have the opportunity to obtain a higher education in the early twentieth century. He had this to say at a talk for Chicano studies students at UC Berkeley in 1977:

The Chicano students that I knew in the thirties at Columbia and elsewhere were very few in number. At Columbia University I didn’t know another graduate student in the department of history or political science or public law, which is where I did my work. Neither were there many of us in the undergraduate institutions in Southern California where I went to college at Occidental. I remember, I think it was in 1925, out of sheer curiosity I inquired among my friends at UCLA, USC, Pomona, Whittier and all of that cluster of colleges in the south, and I could only identify six of us in all of those places. Of course, possibly that wasn’t a good count because even then there were some Chicanos who had already given up their identity. They had become anything but Mexicans. In those days, we didn’t talk about Chicanos. You were either a Mexicano or you were not.

His skills in English and consequent academic achievements were a relative anomaly among the bracero and Mexican American communities due to there being a dearth of bilingual and English language education resources at the time of his youth. According to Galarza, not until the latter half of the twentieth century did the federal government take the concept of bilingual education and English as a second language (ESL) education seriously and fund it in any substantial fashion. And, as he notes in his oral history, once funding did increase there remained a system that overlooked the intricacies of bilingual education; advisory committees in Washington attempted to regulate the bilingual and ESL instruction from afar, and their distance resulted in curriculum that was incongruent with students’ needs.

Concerned about this oversight, Galarza explains that he and other instructors working in bilingual education were actively challenging the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and the Office of Bilingual Education in the 1970s, and had begun to see success. As he says in the oral history, he felt their work “has been so effective, even modest as it is, that it has created waves that have become very ominous to them.”

And beyond his pushing for better, more personalized bilingual education curriculum on an institutional level, Galarza—believing that Spanish literacy had to precede English instruction—took it upon himself to craft and publish what he called “Mini-Libros,” easy-to-read Spanish texts that he designed for use in the classroom and hoped would engage young readers. So as to make students as comfortable as possible, the Mini-Libros even contained vocabulary specific to Mexico and the working-class immigrants coming to the United States at the time.

These actions were especially timely because Mexican immigration into the US was greatly increasing in the 1960s and ’70s, a topic thoroughly discussed in the interview. Galarza recognized the wealth of challenges—from housing to employment to education—that came with incorporating such a massive population into the fabric of American society, and identified the issues of literacy and English proficiency as those he was most eager to help resolve.

Each summer in his undergraduate years Galarzo would return to Sacramento to do what he called “bread and butter work” in the farms and the cannery. Later, when he left California to study at Columbia and the path home was no longer so easily negotiated, his community’s want of literacy became a major concern, in part his due to its personal impact:

I began to be disturbed by the lack of news from home. My family and my friends back in Sacramento were not writers. They didn’t know, many of them, how to write…When I realized after my third or fourth year back in the East that this was happening to me, I became very disturbed. And while we stayed in the East another six years, that feeling never left me that what was happening back in California in all the towns that I knew and where I had worked, I was not keeping abreast of.

Galarza believed that the Mexican immigrant children coming into the school system in the mid-twentieth century had to be brought into the fold of American life, to be “acculturated,” in his words, so as to avoid the fate of his own family and community. And such acculturation could not begin with a hard-and-fast imposition of English instruction, something he believed would only further alienate the newly arrived immigrants, accelerate the creation of insular communities, and complicate their path to prosperity in the US. He viewed bilingual education as the obvious answer to this challenge. It would help a child, as he noted in his oral history, to “recognize—to get into—and become familiar with this strange environment into which he’s been dropped.”

Galarza’s oral history is an invaluable glimpse into the subtle divides of his time: for each acknowledgement of how badly the “American hosts” have treated Mexican Americans, he has another remark on the myopia of Mexican American activists due to their protests against acculturation—something he believed was “largely for the purposes of propaganda.” And beyond these commentaries, he proves to be equally invaluable as a representation of a steadfast activism that lacks glamour and prefers actions to words. Galarza identified the challenges of his time and repeatedly asked the central question: what to do about it?

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

Adam Hagen recently graduated UC Berkeley with majors in Spanish linguistics and history. Adam worked as a student editor for the Oral History Center and was also a member of the editing staff of Clio’s Scroll, the Berkeley Undergraduate History Journal.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has more than thirty holdings by Ernesto Galarza, including poems, books, reports, pamphlets, conference proceedings, and audio of talks and panel discussions. From the UC Library Search, go to “Advanced Search,” select “UC Berkeley special collections and archives,” and in the search field, enter Ernesto Galarza.

The Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project provides a rare, firsthand look at the development of the field of Chicana/o studies over the last fifty years, as well as unique insight into the lives and careers of the pioneering scholars who shaped it.

The Oral History Center digital collection contains additional oral histories of Mexican American activists, such as Hope Mendoza Schechter and Herman E. Gallegos. More can be found by searching “Mexican American community” or “Mexican American activism” on the Oral History Center home page.

Ernesto Galarza’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s Advocacy and Philanthropy—Individual Interviews collection. Read more about the collection in the article by Lauren Sheehan-Clark, “Helping Hands: A Guide to the Oral History Center’s Advocacy and Philanthropy Individual Interviews.”

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Connection, Insight, Inspiration, Truth: Berkeley undergraduates reflect on oral history

“I was just one of thousands of people over the years who have done the little things necessary to create and to pass on personal narratives of the past.” —Mollie Appel-Turner

Introduction: Thoughts on the Production of Oral History and Its Importance

by Serena Ingalls, class of 2023

Like many of my student co-workers at the Oral History Center (OHC), I have recently graduated from UC Berkeley. Graduation from college is a major milestone, and I find myself looking back at all of my different experiences at Cal: classes, clubs, the pandemic, and my job as a student editor and researcher at the Oral History Center. My job in oral history in particular is a point of contemplation, as I’ve spent many hours in this role and it’s a unique experience that only a handful of other students can relate to. I find myself wondering, how has this job impacted me and my view of the world? How has my work in this role contributed to the field of history?

Before closing the UC Berkeley chapter in our lives and moving on to other post-grad interests, we as the student editors took the time to reflect upon our work at the Oral History Center and what it means to us. We hope that you’ll enjoy stepping into our world as student editors in oral history, just as we have enjoyed the experience of getting to know the many fascinating individuals in our oral history archive.

Editor’s note: Our team’s student editors serve critical functions in our oral history production, analyzing entire transcripts to write discursive tables of contents, entering interviewee comments, editing front matter, writing abstracts, and more. They do the work of professional editors and we would not be able to keep up our pace of interviews without them.

Mollie Appel-Turner: Oral History and Connection

Working for the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library while pursuing a history degree was both deeply rewarding and extremely unfamiliar. My area of interest when it comes to history has always been western medieval Europe. While there are plenty of sources from the era where people recount their life experiences, I always had an awareness of the massive separation—temporal, cultural, and physical—between myself and the speaker. At the Oral History Center, I was keenly aware that the work that I was doing on oral histories was with the ultimate goal of preserving knowledge for future generations. But for the time being, that gulf I was used to, which to me practically defined the work I did as history, was simply not present. In my time outside of work, I also spent a fair chunk of time reading people’s personal accounts. While these accounts differed in many ways from the oral histories that I worked on, as time passed, I came to see these different kinds of personal accounts as reflections of one another. I would frequently stop in the middle of my shift, cursor blinking next to a spelling error, and think about how I was just one of thousands of people over the years who have done the little things necessary to create and to pass on personal narratives of the past. The immediacy, and modernity of the accounts that I worked on at the Oral History Center, rather than widening the distance I felt between me and the medieval people I studied, made me feel closer to them in a way that I did not expect.

Mollie Appel-Turner joined the UC Berkeley Oral History Center as a student editor in fall 2021. She recently graduated with a degree in history with a concentration in medieval history.

Shannon White: Oral History and Inspiration

In my time at the Oral History Center, I have worked on and witnessed the publication of interviews from an innumerable variety of narrators, including artists, writers, curators, academics, conservationists, and otherwise “ordinary” people with extraordinary stories to tell. I recall the first oral history I worked on upon joining the Center: Thomas Gaehtgens, former director of the Getty Research Institute, whose interview was not only incredibly detailed but also quite interesting to read. More recently, I have helped edit interviews from the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project, the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program.

As a member of the OHC’s editorial team, most of my work is behind the scenes and prior to publication. I see these interviews at almost every stage in production. By the time an oral history transcript is finalized, I have generally read through it in its entirety several times and am quite familiar with the contents; as such, I interact with oral history at multiple levels. This experience has ultimately helped form and maintain my view of oral history as an inherently dynamic, interactive record—a form of living history.

The final oral history is a labor of many people to produce, with several rounds of edits and review that heavily draw from the narrator’s own input, and as such possesses a strong sense of the narrator’s personal style: how they speak, what they consider important or even essential for understanding their stories, their sense of humor, and what elements of the initial oral interview they would prefer to keep private.

The result is a distinctively humanizing portrayal of the narrator that arises from the nature of oral history as a lightly edited, audio-based interview format. The reliance on the “oral” aspect of oral history means that, bar serious editing, the published transcripts of interviews from the OHC tend to preserve a great deal of the tone of the original audio recording, including quirks of speech unique to each narrator. My personal favorite detail is always the bracketed notes included by the transcriber to indicate when someone is laughing, a phenomenon that often accompanies the conversation between interviewer and narrator and, in my opinion, highlights the deeply personal nature of these interviews.

By sheer virtue of the volume of in-progress oral histories I interact with, I find that in time they become almost a part of you—there are so many narrators whose words and stories I remember, and whose work I have actively sought out after encountering their oral histories. For example, I became interested in Bay Area arts institutions after reading the interview of a San Francisco Opera board member; my own undergraduate research has been informed in no small part by border theory, a concept I was first introduced to by the narrators of the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project; and my work on the oral histories of California politicians has contributed to my awareness of the history of the state’s politics. Oral history is intimate and alive, and its existence has the unique ability to inform and inspire those who engage with it.

Shannon White is a recent UC Berkeley graduate in the Department of Ancient Greek and Roman Studies. They were an undergraduate research apprentice in the Nemea Center under Dr. Kim Shelton and a member of the editing staff for the Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics. Shannon worked as an editorial assistant for the Oral History Center.

Serena Ingalls: Oral History and Insight

Before working at the Oral History Center as a student editorial and research assistant, my interactions with oral history were limited. As a history major, it was a topic occasionally mentioned in my classes at Cal. I could understand the value in oral history as a way of filling in gaps in the historical record and giving a voice to those who were excluded from the written record. After I began my work with the OHC, however, I gained a new appreciation for oral history. This change in perspective came after seeing firsthand the immense effort that goes into producing oral histories to be shared with the public, and from reading the oral histories in our archive.

At the Oral History Center, I’ve worked in two roles. One of my roles is as a research assistant. In order to promote our archive and share our interviews with the public, we post on social media about relevant historical anniversaries (25th, 50th, 75th, 100th). I research these anniversaries and then search the archive to see if we have content that references these historical events. It’s surprising how many specific events are mentioned by interviewees, so I never discount an event without checking first with the archive. If there is one event that is very historically significant and has several interviews that reference it, sometimes I’ll write an article on the subject for the OHC. My other role is as an editorial assistant. Editorial assistants are part of the process of readying an oral history for publication. Student editorial assistants have a range of responsibilities during the editorial process which include inputting corrections from narrators, writing the table of contents, and more. Editing the oral history is a collaborative process, and it can take months or even years before an oral history is fully ready for publication. Once an oral history is completed and shared with the public, all who have worked on a particular oral history know the narrator inside and out.

The OHC has an enormous archive of interviews with narrators who have incredible insight on the history of California and beyond. Their voices provide knowledge, but more critically, they add life to these historical periods. The interviews are at times surprising, heartbreaking, and even funny, and no two interviewees have the same story. Each interview is a unique combination of the mundane and the extraordinary, just like the life of any person.

“Each interview is a unique combination of the mundane and the extraordinary, just like the life of any person.” —Serena Ingalls

Serena Ingalls recently graduated UC Berkeley with majors in history and French. She is an editorial and research assistant for the Oral History Center. Serena came up with the idea for an article about what it’s like to work on oral histories when she worked on an article about the seventy-fifth anniversary of the tape recorder.

William Cooke: Oral History and Truth

A few short months ago, I graduated from UC Berkeley. I have completed 12 political science courses; written dozens of sports articles for Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian; struggled my way through one too many required science classes; and penned more than a few essays en route to a minor in history.

As a journalist and student, determining and advancing truth was at the heart of everything I did. For example, in order to make a sound political science argument about the role of agency in a democracy, I could not reinvent what Harriet Jacobs wrote in her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Desiderius Erasmus had something specific to say about tyranny. What was it, exactly? Did Cal’s football team run or pass the ball more often on third down? If the United States federal government really did assume a different position towards organized labor after World War II, what evidence supports that claim?

The answers to my own questions, or the questions my professors asked of me, had to be completely truthful. I certainly couldn’t say that I didn’t have an answer to an essay prompt.

Oral history is a little bit different. When I first began working here last year, I couldn’t help but be skeptical. An interviewee in her eighties cannot with absolute accuracy remember her childhood years during the Great Depression, or her immediate reaction to the assassination of President Kennedy. Memory fails people all the time. A story might be true on the whole, I thought to myself, but the details might not. And what use was the answer “I don’t know?” That might be the truth, but what good is an oral history in which there are gaps?

In short, how could a researcher possibly find use in an incomplete, possibly inaccurate story told by someone fifty years after the fact?

Of course, these questions are not on my mind as I write a table of contents or fix formatting issues on a transcript. My work can be tedious at times. As someone whose mind likes to stay busy, I don’t mind. But every now and then I will stop and think critically about what I’m reading and how it relates to my role as a student, journalist, and assistant at the Oral History Center; namely, promoting truth.

I soon came to terms with the fact that oral histories cannot be totally accurate and that in an important way they are true. While the historian attempts to explain how people in the past saw themselves, their situation or others in very broad terms, the oral history provides insight into how a creator of history currently thinks of her past self, a valuable perspective for social scientists of all stripes. An interviewee might have felt more anxious than nervous at a certain moment in history, but how he remembers the past is also an important part of history. What good is there in knowing the true happenings if we do not know how the living, breathing makers of history think about what happened?

And for that reason, I have come to realize that oral history isn’t impure, or less true. I do still read the oral histories I work on with a wary eye. But I don’t worry about their truthfulness like I first did back in the spring of 2022. Instead, each time I complete my portion of a project, I feel a sense of gratification for having helped keep history alive. Because true history is not a fixed thing. It lives in the minds of everyone who has experienced it.

William Cooke recently graduated UC Berkeley with a major in political science and minor in history. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Works

Serena Ingalls, Saving the Spoken Word: Audio Recording Devices in Oral History

Mollie Appel-Turner, Shirley Chisholm, Women Political Leaders, and the Oral History Center collection

William Cooke, Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond and Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley

Shannon White, “I take this obligation freely:” Recalling UC Berkeley’s loyalty oath controversy

Jill Schlessinger, editor, A peaceful silence: Berkeley undergrads reflect on remote employment during the pandemic

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Primary Sources: Reports of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry Palestine, 1944-1946

A recent acquisition of the Library, Reports of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry Palestine, 1944-1946, provides access to the papers of this committee created in 1945 to “study the situation of Jewish survivors in Europe and the problems connected with their resettlement in Palestine.

“The committee was charged with gathering information and making recommendations on 1) the effect of Jewish immigration and resettlement on the political, economic, and social conditions in Palestine; and (2) the position of surviving Jews in Europe and the possibility of relieving the problem by repatriation or resettlement of the survivors in Palestine and other non-European countries. The committee called for a unitary state rather than partition based on ethnicity or religious profession. The records include AACI reference files, evidence submitted to the committee, transcripts of hearings, AACI reports, and papers of the Anglo-American Cabinet Committee.”

Primary Sources: Testaments to the Holocaust, Documents and Rare Printed Materials from the Weiner Library, London

A recent acquisition, Testaments to the Holocaust, Dococuments and Rare Printed Materials from the Weiner Library, London, provides access to the “first archive to collect evidence from the Holocaust and the anti-semitic activities of the German Nazi party. It contains documentary evidence collected in several different programmes: the eyewitness accounts which were collected before, during and after the Second World War, from people fleeing the Nazi oppression, a large collection of photographs of pre-war Jewish life, the activities of the Nazis, and the ghettoes and camps, a collection of postcards of synagogues in Germany and eastern Europe, most since destroyed, a unique collection of Nazi propaganda publications including a large collection of ‘educational’ children’s’ books, and the card index of biographical details of prominent figures in Nazi Germany, many with portrait photographs. Pamphlets, bulletins and journals published by the Wiener Library to record and disseminate the research of the Institute are also included. 75% of the content is written in German.”

Primary sources: Russian language historical ebook collections

This post highlights some of the Library’s acquisitions of Russian-language historical ebook collections that may have escaped your notice.

Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda ebook collection

Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda ebook collection

East View has digitized a collection of 280 e-books that are most emblematic of Soviet anti-religious fervor. They were published mainly in the 1920s and 1930s on a variety of atheist or anti-religious topics, with titles including Christianity versus Communism, Church versus Democracy, and The Trial of God.

Another collection from East View of 116 ebooks, originally published from 1928 to 1948, relating to the golden age of Soviet Cinema.

An ebook collection of 778 works from Brill Online. It represents works of all Russian literary avant-garde schools, most published betwen 1910-1940. According to the publisher, “the strength of this collection is in its sheer range. It contains many rare and intriguingly obscure books, as well as well-known and critically acclaimed texts, almanacs, periodicals, literary manifests. This makes it a gold mine for art historians and literary scholars alike. Represented in it are more than 30 literary groups without which the history of twentieth-century Russian literature would have been very different. Among the groups included are the Ego-Futurists and Cubo-Futurists, the Imaginists, the Constructivists, the Biocosmists, and the infamous nichevoki – who, in their most radical manifestoes, professed complete abstinence from literary creation.”