Tag: Getty Trust

Senga Nengudi: Black Avant-Garde Visual and Performance Artist

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative (AAAHI), Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted several oral history interviews with the avant-garde artist Senga Nengudi. This interview is one of several AAAHI oral histories exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and highlights Nengudi’s contributions to visual and performance art.

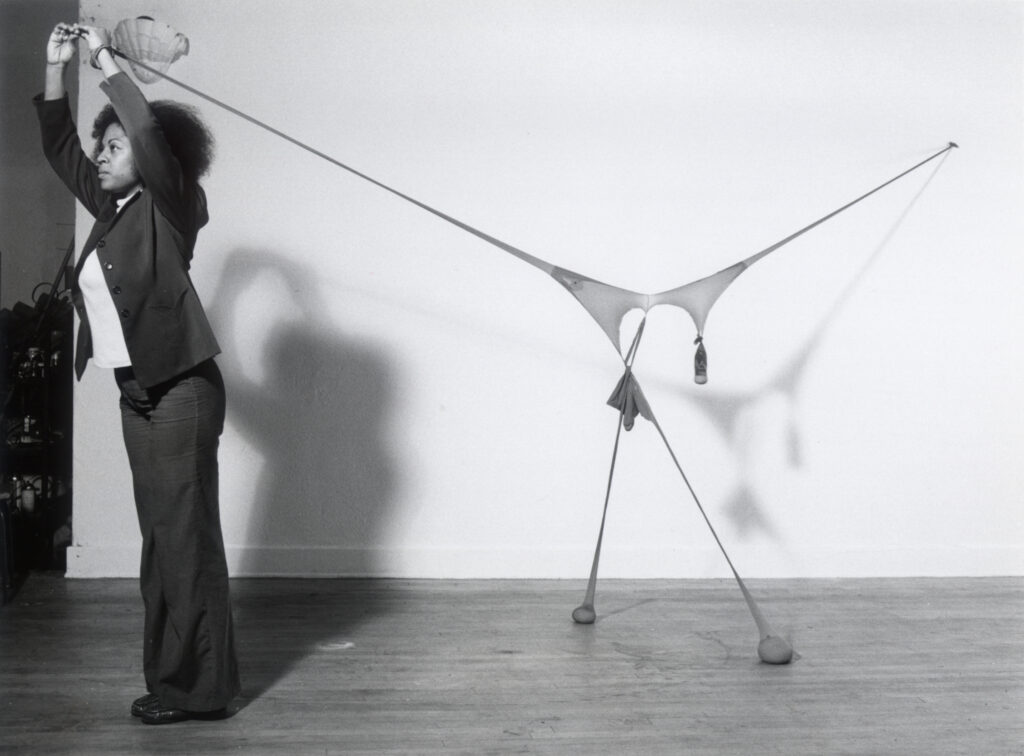

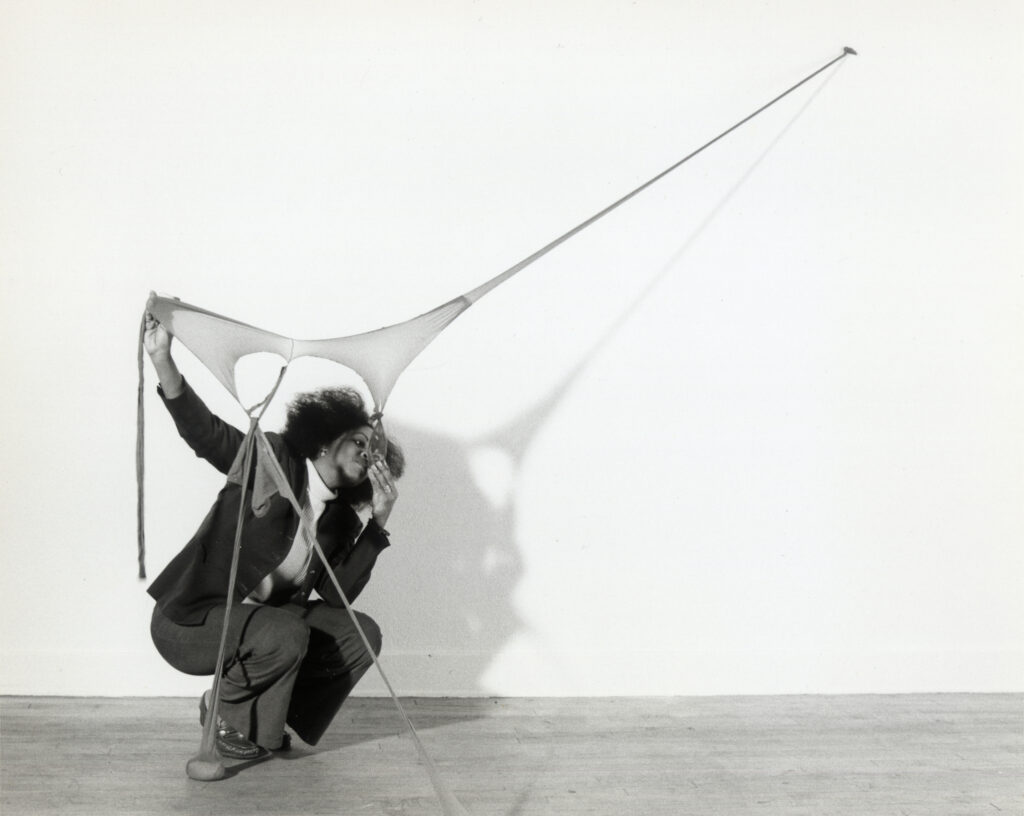

Senga Nengudi is an avant-garde artist best known for her abstract sculpture and performance art. Nengudi was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943 and moved to Los Angeles, California, at a young age. She attended California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA) for both her undergraduate and master’s work, as well as completed a program at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan. Nengudi was active in the avant-garde Black art scenes in Los Angeles and New York during the 1960s and 1970s, and was a member of the Studio Z Collective. She is best known for her R.S.V.P. (Répondez s’il vous plaît) Series featuring pantyhose, which she began in 1975. Nengudi is the recipient of many awards, including the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award in 2005, the Anonymous Was a Woman Award in 2005, the Denver Art Museum Key Award in 2019, and was elected as a member to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2020. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Senga Nengudi was still in elementary school when she and her mother moved to Los Angeles in the early 1950s. Despite a brief stint in New York, for more than thirty years she lived in the greater Los Angeles area first as a child; as a student at CSULA; as an artist and active member of the Studio Z Collection; and as a young mother. That Nengudi called Los Angeles home for so long meant that her formative years of creative expression and early artistic networks sprang from the Southland.

Looking back, Nengudi credits her mother with providing a creative foundation.

“…she was very, very, very conscious of the home and making something home, and so she would decorate the house. And then, say like three years later, she would repaint the walls, she would change the upholstery, she would do all those kinds of things. She was very aesthetically aware, as well as needed a particular beauty in her home to feel good.”

And Nengudi expressed her own creativity through several outlets, remembering, “It’s always been a deal between art and dance with me…” Indeed, during her undergraduate years at CSULA, she chose to major in art and minor in dance—a pairing which supports much of her work.

In the mid-1970s, Nengudi found an outlet to express her love of performance through the Studio Z Collective—a collective of artists interested in improvisation that continued into the 1980s. In addition to Nengudi, Studio Z was comprised of Houston Conwill, David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, and occasionally other artists including Franklin Parker and Ulysses Jenkins. Her relationships with these artists also had a great impact on Nengudi’s artistic career. Thinking of Studio Z’s contribution to her 1978 performance Ceremony for Freeway Fets, which took place under a freeway overpass on Pico Blvd., she muses that “we all kind of supported each other in our efforts.”

Nengudi also found early support from Los Angeles-based gallery owners like Greg Pitts at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery, as well as Brockman Gallery’s Alonzo and Dale Davis. In fact, Brockman Gallery’s dispersal of CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] funds helped employ artists like Nengudi and Maren Hassinger.

Hassinger remains Nengudi’s longtime creative collaborator. Nengudi recalls that the connection between the two was immediate, “We just kind of instantly became friends, because there was this commonality. She was involved with dance, she was involved with sculpture, all that kind of stuff.” And to why this collaboration with Hassinger has sustained both the passing of years and geographical distance, Nengudi explains:

“Because we believe so much in collaboration. We believe in unity. We believe in bringing the best out in each other…Even though our background is different, our interests are the same. It’s always been dance, performance, sculpture, movement, and this commitment to our art. And when we had some really funky times and we were 2,000 miles apart, the thing that held us together was this commitment to art. And so that kind of carried us through the most difficult things…So all these life events were going on, but the constant was our ability to connect and think and make happen.”

Nengudi’s most recognizable series of work is R.S.V.P., which she started in the mid-1970s. The R.S.V.P. Series, or Répondez s’il vous plaît (respond, please), demonstrated Nengudi’s experimentation with nylon pantyhose. Importantly, Nengudi began working in this medium after the birth of her first son, when she was especially interested in the elastic nature of a woman’s body. She recalls,

“So yes, the explorations were really exciting. I put eggs in them, I broke eggs in them…I used white glue, I used hot glue, which obviously didn’t last that long. I tried everything—resin. Again, it dissolved in the resin. So really, as I was developing the series, it was all about exploring the material…And it took a while to get to…the sand, where I just noticed that…once in the nylons, it had such sensuality to it, because it had this kind of natural body form from the weight of the sand.”

Given the experimental nature of her sand-filled nylon pieces, Nengudi explains, “I thought about them as sculpture first. I did not develop them thinking that I would perform in them.” But Nengudi eventually did embrace the performative potential of these sculptures, even engaging Hassinger to perform with them at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery in 1977 by entwining her body with the material, manipulating it, even dancing with it.

Nengudi has lived in Colorado since the 1980s, and continues to stimulate audiences by creating work that plays with the line between sculpture, installation, and performance in space. However, she has also made significant contributions as an arts educator, especially at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and as an advocate of the arts. Namely, she established a community art gallery called ARTSpace in Colorado Springs so that “artists could show their work” and learn “what it takes to have an art exhibit.” The added bonus, of course, was that “the community could come in and see the artwork. It was right there for them.” For someone whose early exposure to creative expression was so formative to her artistic practice, this is a logical next step to engage new generations of artists and viewers. It also connects with her decades-long entreaty to audiences: “respond, please.”

To learn more about Senga Nengudi’s life and work, check out her oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

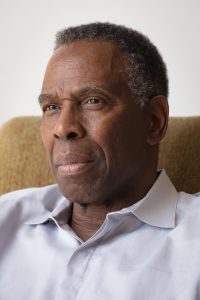

Richard Mayhew: Painting Mindscapes and Searching for Sensitivity

In March 2019, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I had the pleasure of conducting a series of oral history interviews with artist and educator Richard Mayhew for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative. Mayhew’s most recognizable work includes paintings of abstract and brightly-colored landscapes—what he calls mindscapes.

Richard Mayhew is a painter, as well as a retired professor of art. He was born on Long Island, New York, and displayed an early interest in art. He studied at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, the Art Students League of New York, the Pratt Institute, and Columbia University. Mayhew received a John Hay Whitney Fellowship in 1958 to live and study in Europe in the early 1960s. He joined Spiral in 1963 and was a member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC). Mayhew has taught at many universities and art institutions, including Hunter College, Pennsylvania State University, San José State University, Sonoma State University, and University of California Santa Cruz.

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Mayhew’s interview detailed his incredible life and inventive work, as well as his deep connections to communities of artists across the country, and indeed across generations. For instance, Mayhew was a member of a group of Black artists called Spiral, which met to discuss both their work and their connection to the Civil Rights Movement. Spiral started in 1963 at the urging of A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to “form a contingent of artists for the March on Washington” that same year.

Mayhew recalls that “the original group of elders” in Spiral included Charles Alson, Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Felrath Hines, and Hale Woodruff. But this soon became an intergenerational group. In speaking about the formation of Spiral, Mayhew also remembers its network of visual and performing artists across the country:

“But also, [A.] Philip Randolph wanted not just the visual artists, he wanted all African American artists that wouldn’t be in the New York area. So we called the artists in Missouri and Chicago and also Los Angeles about this idea that Philip Randolph wanted a contingent of artists. So they made contact with them over there. We didn’t have all the people together, so Ralph Ellison came there and he was talking about—I don’t remember all the names now of the composers, and also directors of the theaters in New York which were Afro-American. That was part of the idea, the contingent not just be the visual artists, but all the areas of arts in that area.”

Another unique aspect of this interview was Mayhew’s reflection on his African American and Indigenous backgrounds, and how they influenced his relationship to art and nature. In thinking about how his identity connected to his artistic vision, Mayhew explained,

“Mine was more out of the African American and Native American heritage, in terms of the love of nature and also the respect for nature, because nature’s involved in reinventing itself. That was what’s going on, in terms of African American and Native American sensibility. They constant[ly] reinvented themsel[ves] and constantly grew and matured and survived. That was my connection to nature and the fascination, almost until today. I’m still trying to paint that feeling.”

To learn more about Richard Mayhew’s life and work, read his oral history transcript here. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Merritt Price: Building the Design Department at the Getty

I’ve been interviewing for the J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Project for several years, and it is a continual pleasure to learn about employees and operations across this large organization. But rarely do I come across a longtime employee whose work for the Getty Trust has taken them across departments, programs, and even physical sites. This is what made my interview with Merritt Price so unique. In fall 2020, I conducted a series of oral history interviews with Merritt Price, the former head of the Design Department (now Museum Design Department, 1995-2020).

Merritt Price is the former head of the Design Department (now Museum Design Department) at the J. Paul Getty Trust, which he ran from 1995-2020. Price grew up in Belleville, Ontario, Canada, and moved to Toronto in 1980 to attend the Ontario College of Art (now Ontario College of Art and Design). Price worked for several design firms in Toronto, including starting his own practice called Tangram, before accepting a position with the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1990. He began his work with the J. Paul Getty Trust in 1995, founding what was then the Exhibition Design Department.

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

When Merritt Price joined the Getty in 1995, he needed to build the then-Exhibition Design Department from the ground up. This involved defining the Department’s work as not only about aesthetic concerns like text labels and display cases, but also about a larger visitor experience—where museum goers walk and sit, and how they interact with the space. As such, Price assembled a multidisciplinary team to create “one-stop shopping” for design at the Getty Trust.

In thinking about why it was important for the Getty to establish the Design Department, rather than rely on design consultants, Price explained,

“I think it’s also noteworthy that working in-house at a museum, as opposed to being in a consulting office that might be doing design for museums or galleries, that you have a different perspective, because you’re right in it and you’re in it all the time. It’s a little bit more laboratory-like where your work product is right there outside the door in the gallery. You can walk through it, you can see visitors using it.”

Over the twenty-five years he worked at the Getty, Price and his team handled designs for major projects in the organization’s history. Indeed, Price’s first task included design work for the Getty Center, which opened to the public in 1997. In addition to addressing gallery spaces, Price also created a wayfinding system with signposts to orient visitors on the large Getty Center campus. He later worked on the redesigns at the Getty Villa.

Price and his team also designed for exhibitions across the Getty Trust, including Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen, Foundry to Finish: The Making of a Bronze Sculpture, and Michelangelo: Mind of the Master. However, Price was particularly involved in the exhibition J. Paul Getty Life and Legacy, for which he pitched the concept and led a team of curators in creating content. Listen as he explains the idea behind the show:

I have a background in museum work, and I felt confident speaking with Mr. Price about his vision for museum spaces and the practical necessities like spacing around pedestals. However, I still learned a great deal about technical innovations, as well as the impact of design both on exhibitions and on the other spaces in which visitors use—from trams to gift shops to restaurants. This interview was both personally enjoyable and is a great source of information about the construction and redesign of the Getty Center and the Getty Villa.

To learn more about Merritt Price’s life and work, read his oral history transcript here. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Charles Gaines: The Criticality and Aesthetics of the System

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted a series of oral history interviews with the conceptual artist Charles Gaines. This interview was the first of several exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and celebrates Gaines’s extraordinary artistic contributions.

Charles Gaines is an artist specializing in conceptual art, as well as a professor of art at California Institute of the Arts. Gaines was born in South Carolina in 1944, but grew up in Newark, New Jersey. He attended Arts High School in Newark, graduated from Jersey City State College in 1966, and earned an MFA from the School of Art and Design at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1967. Beginning in 1967, he taught at several colleges, including Mississippi Valley State College, Fresno State University, and California Institute of the Arts. Gaines has written several academic texts, including “Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism” in 1993 and “Reconsidering Metaphor/Metonymy: Art and the Suppression of Thought” in 2009. His influential artwork includes Manifesto Series, Numbers and Trees, and Sound Text; and he exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2015. Gaines is the recipient of several awards, including Guggenheim Fellowship in 2013 and REDCAT Award in 2018. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Hearing about Charles Gaines’s upbringing was especially helpful in framing his approaches to art. For example, he spoke about his mother’s influence on his life–particularly her musical inclinations. Though Gaines concentrated his early artistic studies on the visual arts, he also had a passion for music, eventually becoming a professional drummer. This connection to musicality and music theory features prominently in his conceptual works like Snake River and Manifestos. Indeed, in his Manifestos Series, Gaines turned the text of political manifestos into musical compositions based on a system he devised. He recalled, “Unconsciously, I began thinking about music as a kind of mathematics and this connection with text and language; I began to see the connection to language and systems.”

speakers, hanging speaker shelves. Photograph by Frederik Nilsen.

Further, Gaines shared about his exploration of conceptual work in the 1970s, and his consequential transition from an abstract painter to a conceptual artist:

Well as I said, those big abstraction paintings turned into these process-oriented works, and so that work demonstrated an interest in a systematic approach. It was a part of my research. I was looking for an alternate way of making work that was not based upon the creative imagination, was not based upon subjective expression.

This transition period also coincided with an eighteen-month sabbatical from teaching at Fresno State University from 1974 to 1975, when Gaines, his wife, and infant son moved to New York to explore his professional art practice. He recalled of the conceptual artists he met there:

But I did at that time, during that time in New York, become much more familiar with conceptualists, with what the conceptualists were doing. At that time, it provided a context for me. It was just before I started working with numbers but I was working with systems already, and so I felt that it’s true that, of anybody, my work, the language of my work fits best with those conceptualists.

Another major theme in Gaines’s interviews was his many years teaching art at colleges across the country, including the challenges of teaching at what he deemed conservative institutions. Despite these challenges, Gaines always looked for ways to mentor his students by not only helping them improve the quality of their work, but also by sharing his own insights into how to navigate the art world. He explained:

The thing I would always give my students advice about is that you can’t control career. That’s something that you shouldn’t even be thinking about. You should only think about the work, and you should also think about exhibiting the work, which I think is different from a career. You need to show people the work, so you make the work and try to get people to see it. In that process, something might happen, you can’t make it happen. In almost every story about how careers get kicked off, it’s because you happen to be at a right place at the right time, and somebody who matters notices something, and then things sort of roll into place…Ultimately, it’s the work that’s going to get you the exposure.

In addition to his own works and teaching career, Gaines has also made many important contributions to the art world through his theoretical writing and curation of exhibitions. In 1993, he co-curated Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism with Catherine Lord at the University of California, Irvine in 1993. This show, and Gaines’s catalog piece, explored racism in the art world by displaying Black artists’ work alongside reviews from (largely white) art critics, and questioned how and why they misread this work. Of this important exhibition, Gaines explained:

Well, I chose artists who were actively producing in the art world, and known to people. In a couple of cases, I showed a couple of people who were at an early part of their career, like Renée Green, for example, just started her career. But there were other people like Lorna Simpson and Fred Wilson, Adrian Piper, were completely well-known. The fact that they’re well-known artists was important to me because it allowed me to underscore this point that I was making: that is that there’s not much writing on the work of artists, even if they’re well known. The writing that there is [is] marginalized around the idea of race. The writers who wrote about [them] often thought they were writing positively about the work. They didn’t think that the way they approached the work was, in fact, marginalizing.

To learn more about Charles Gaines’s life and work, check out his oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

David C. Driskell: Life Among the Pines

In April 2019, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I had the privilege of conducting a series of oral history interviews with artist and educator David C. Driskell for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative. David and his wife, Thelma, welcomed us into their home, where we spent hours speaking with David about his singular life and extraordinary contributions to art and African American art history. It was a surreal experience to sit behind the camera and look around at beautiful works of art while David skillfully engaged us with stories from his life and work. In recounting his past, David employed accents and well-timed jokes that had us in stitches. It was a pleasure to watch a gifted storyteller at work.

One year later, I learned from Bridget that this kind, funny, and smart man had passed away from complications due to the coronavirus on April 1, 2020. In a year filled with so much loss and change, David’s passing still hit hard. With David’s passing, the world lost not only a bright personality, but also a brilliant mind who championed the field of African American art history. And despite the uncertainty of these early days of the pandemic, I am happy to say that the Oral History Center was able to expedite the finalization of David’s oral history transcript, which is now available to the public.

Now another April has arrived. At the Oral History Center our work remains remote, but people across the country have been vaccinated against the coronavirus, and there is hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. It is past time to take stock and reflect on those we have lost and the stories that remain with us. For me, David Driskell’s interview is one such story with staying power.

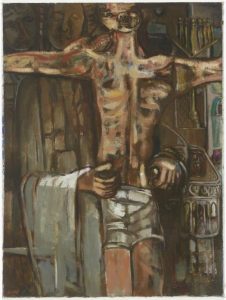

David C. Driskell was an artist and professor of art. He was born in Georgia in 1931, but mainly grew up in North Carolina. Driskell graduated from Howard University with a degree in painting and art history in 1955, attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1953, and earned an MFA from Catholic University in 1962, as well as a study certificate in art history from Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie in 1964. Beginning in 1955, he taught at several colleges, including Talladega College; Howard University; Fisk University; and the University of Maryland, College Park. His influential artwork includes Young Pines Growing, Behold Thy Son, Of Thee I Weep, and Ghetto Wall #2. Driskell has curated important shows highlighting African American art history, including Two Centuries of Black American Art and Hidden Heritage: Afro-American Art, 1800-1950. He also helped establish The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, College Park, in 2001. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Throughout his many years making art, David experimented with different media and subjects, often with the recurring theme of pine trees. Yet one of his most memorable pieces is Behold Thy Son from 1956, which is now at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. David painted this pietà – a subject in Christian art depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus – in response to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. For many observers, this image captured the zeitgeist of the early Civil Rights movement.

Listen as David speaks about making this important piece:

When Bridget asked how David felt about Behold Thy Son over sixty years after painting it, he replied, “I think it is dated and tied to a time and period, but the fight goes on. It’s also showing you that time hasn’t changed that much. [Eric Garner and] ‘I can’t breathe.’ ” Indeed, the subject of violence against Black bodies remains tragically evergreen.

And yet, in part because of this turmoil for African Americans at midcentury, David found renewed artistic inspiration in the serenity of nature – especially pine trees. Listen as he explains this shift in his work:

David was indeed a talented artist and important educator, as Bridget eulogized so well in her obituary on ArtForum last year. But our oral history interviews with him also highlighted the fact that he was a deeply religious man, one who connected his spirituality and creativity with his passion for gardening. During an interview session after church on Palm Sunday, David said of these links between nature and religion, “From dust and dirt thou came, and so dust to dirt thou goest. I’ve got to be part of that process.”

He further explained:

“So gardening is to me like painting, in a way. It’s a part of the process of this creative spirit that I feel so close to. Can’t wait to get [to the house in Maine] and I often go to the garden before I go to the studio…Gardening is a part of my life. It’s a part of that kind of spiritual regeneration that comes with the natural process. It isn’t for me so much the biblical reference.”

As a further measure of the man, when we were wrapping up our final interview session, we asked David for his concluding thoughts, and he said, “Well, maybe the final say is none of this I could be doing without family.” He went on to praise his wife, Thelma, in particular for supporting his art career when it was just a dream.

To learn more about David C. Driskell’s extraordinary life and work, read his oral history transcript and watch his interview in full here, here, and here. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Kenneth Hamma: Antiquities and Technology at the Getty

Kenneth Hamma is a former employee of the J. Paul Getty Trust, where he held several positions, including associate curator of Antiquities and executive director of Digital Policy and Initiatives. He attended Stanford University and Princeton University, specializing in art and archaeology. Hamma taught at the University of Southern California, and became associate curator of Antiquities at the Getty Museum in 1987. He then held several positions in information technology at the Getty from 1997 to 2008 before consulting in the same field.

Hamma’s oral history is part of an ongoing series of interviews for the J. Paul Getty Oral History Project. As Hamma worked in many positions in various parts of the Getty Trust for over twenty years, he had a unique perspective about the growth of the institution and its various challenges.

Hamma began his professional career in academia, teaching archaeology and art history at the University of Southern California while also participating in a years-long dig of the ancient city of Marion in Cyprus. Yet, he made connections with the Getty Museum while teaching in the Los Angeles area, and pursued a position as associate curator in the Antiquities Department in 1987, where he worked for ten years. During this time, Hamma helped grow the Getty’s antiquities collection through acquisitions, and even managed a program that brought classical Greek theater like The Odyssey to life at the Getty Villa.

But eventually, Hamma felt it was time to move on and to pursue his interests in information technology. Listen to Hamma describe this professional transition at the Getty:

Hamma’s work in information technology led to him several positions at the Getty: head of Collections Information Planning at the J. Paul Getty Museum (1997-1999); assistant director for Collection Information at the J. Paul Getty Museum (1999-2004); senior advisor for Information Policy at the J. Paul Getty Trust (2002-2004); and executive director of Digital Policy and Initiatives at the J. Paul Getty Trust (2004-2008). In these positions, Hamma fought to create a more cohesive approach to technology and systems Trust-wide at the Getty, as well as for open access to information about its collections. Part of these challenges included changing the Getty’s approach to copyright management. Hamma sometimes faced pushback in allowing more open licensing for the Getty’s collection, but he explained,

“I was always of the opinion that the more open the Museum was, the better…what that meant to me changed over time, partly as I thought about it more but partly also as technology provided opportunities to be more open and more fluid with information. It seemed to me that it was the responsibility of the Museum to take advantage of those in every way that it possibly could.”

Hamma retired in 2008, and worked as an independent consultant for a decade, extending the ideas about information technology management he developed at the Getty to other arts institutions around the country. During his more than twenty years at the Getty, Hamma brought new ideas and changing technologies to the forefront of the Getty’s work, building the foundations for the institution’s current embrace of open content for arts education and research.

To learn more about Kenneth Hamma’s work at the Getty, check out his oral history!

Tradition and Innovation in the J. Paul Getty Trust Paintings Conservation Department

One of the pleasures of interviewing for an ongoing project such as the J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Project is being able to draw connections between ideas and moments in time, and to the individuals who helped shape them. The Paintings Conservation Department at the Getty Trust is one such example. The development of this department mirrors the growth of the Getty from a small museum perched above the Malibu coast to its current iteration as a large organization with international reach. Over the last several years, I have been delighted to interview three people who not only saw this transformation and its impact on the Paintings Conservation Department, but helped build it up: Yvonne Szafran, Mark Leonard, and Joyce Hill Stoner.

Yvonne Szafran was the head of the Paintings Conservation Department from 2010 until her retirement in 2018. She joined the Getty Museum in 1976 through a work-study program in the Antiquities Conservation Department. In 1978, she became a conservator in the Paintings Conservation Department. (Yvonne Szafran: Forty Years of Paintings Conservation at the J. Paul Getty Museum)

Mark Leonard was the head of the Paintings Conservation Department from 1998 until his retirement in 2010. He worked as an assistant conservator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art before joining the Getty as an associate conservator of paintings in 1983. (Mark Leonard: Building New Traditions in Paintings Conservation at the Getty, 1983-2010)

Joyce Hill Stoner is a professor of material culture at the University of Delaware, Director of the University of Delaware Preservation Studies Doctoral Program, and painting conservator for the Winterthur/UD Program in Art Conservation. Dr. Stoner has a long history with the J. Paul Getty Trust, including as a visiting scholar to and traveling with the Paintings Conservation Department in the 1980s, working as the managing editor of Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts, and serving on committees with the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI). (Joyce Hill Stoner: My Life in Art Conservation and Intersections with the Getty)

Through memories that span four decades, these interviews help illuminate the passion, skill, and vision that conservators at the Getty Trust have used to treat some of the world’s finest paintings, and to grow the Paintings Conservation Department into a world-renowned operation.

The years after Mr. Getty’s 1976 passing and the subsequent money his will provided his namesake museum proved to be a heady time to be at the Getty. Szafran recalled that the new capital offered unique opportunities for conservators that they might not have found elsewhere. She explained,

“They were the times at the Getty when the money finally came, acquisitions started rolling in, shall we say. It was such an exciting time to be at the Getty because new paintings were being acquired frequently. So as the youngest member of the Department, I was given great things to work on, just because we were so busy.”

Certainly money opened doors for the Paintings Conservation Department, but in thinking about what made it unique amongst its counterparts at other museums, Szafran, Leonard, and Stoner all spoke about its philosophical approach to conservation—one which differed from the “objective” way many taught art conservation in the mid-century United States. Listen as Leonard explains this subjective approach,

This approach to art conservation started to take shape in the mid-century United States, thanks in part to the influence of European practitioners like John Brealey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—who also happened to be Leonard’s mentor. This style was also reinforced by Andrea Rothe, the former head of the Getty Paintings Conservation Department (1981-1998).

Another experience all three narrators shared was joining the Department for research trips that Rothe planned to Italy in the late 1980s. Stoner, who was already working at Winterthur, joined Rothe, Szafran, Leonard, and longtime Getty conservator Elisabeth Mention on one of these trips. Listen as Stoner recalls these trips that Rothe arranged:

Stoner and the others observed firsthand the differing conservation styles in Italy and engaged in conversation about what approach worked best for not only the Getty, but also for new students in the field. Stoner was actively teaching at Winterthur at the time, and discussed returning to the Getty for specialty training a few years later, videotaping the sessions in order to share them with her students. This willingness to invite non-staff conservators to such events indicates the importance of the Getty in fostering continuing education among its own staff and disseminating these ideas into the rest of the field.

These research trips to Italy also demonstrate that the Getty had an interest in cultivating talent, especially in the Paintings Conservation Department. This may be why a core group of four conservators—Rothe, Szafran, Leonard, and Mention—stayed together for around twenty years.

One thing that became apparent in the course of these interviews is that not all museums have in-house paintings conservation departments. And the fact that the Getty has supported this department from the beginning points to a dedication to succeeding in the field and to support the growing paintings collection in the Getty Museum.

During his tenure as head of the Department (1998-2010), Leonard continued to think about how to build public support for this work and expand international partnerships, especially in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the new access to museums and art collections to the West. His solution was to establish the Paintings Conservation Council. Listen as Leonard discusses his decision to create the Council,

Before joining the Getty Trust Oral History Project, my understanding of art conservation was limited. But in the course of interviewing Szafran, Leonard, and Stoner, I learned not only about treatment and techniques, but also about the important role the Paintings Conservation Department plays in the Getty Trust. Further, an in-depth look at this department underscores the transformation of the Getty into an international arts organization, as well as the people, talent, and innovation that pushed it forward.

To learn more about the Paintings Conservation Department at the Getty Museum, check out oral history interviews with Yvonne Szafran, Mark Leonard, and Joyce Hill Stoner!

Oral History Year in Review: Lessons I’ve Learned

In my years working as an oral historian, I’ve come to learn that the most important skill I have in my professional toolbelt is humility. Even after years of study and completing interview-specific research, I know that in any given oral history, I am never the expert in the room. In recording life histories with narrators, I always walk away with new information and fresh perspectives. Oral history folks call this “sharing authority,” but I also like to think about it as an opportunity for personal growth. And part of this growth requires jumping into new subjects and interview situations that challenge me.

One project that continues to challenge and delight me is the J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Project. I have been working on this project since I joined the Oral History Center (OHC) in 2018, interviewing employees and trustees about the organization’s important contributions to the arts. Also in 2018, the partnership between the Getty Trust and the OHC expanded in order to document the history of prominent African American artists as part of the Getty Research Institute’s (GRI) African American Art History Initiative. Between the two subject areas, the Getty Trust Project represents most of the interviews I have conducted over the last year.

I love that the Getty Trust Project has prompted me to use my background in museums and art history, sometimes forcing me to literally dust off old textbooks. Even so, these interviews have taken me outside my personal art historical comfort zone of Renaissance Italy (I once took an entire course on the works of Michelangelo!), and introduced me to fields from medieval Flemish illuminated manuscripts to twentieth-century American video and performance art. This introduction to various art history specialities has required much study, but also humility in knowing when to defer to the expert.

In the case of the GRI’s African American Art History Initiative, I have had the pleasure to work with one such expert as a co-interviewer: art historian and University of California, Irvine professor Bridget R. Cooks. Cooks has been a delightful addition to the team and a wonderful resource about the artists we interview together. Her academic work in display and criticism added crucial framing to each artist’s story, and her interest in and respect for the people we interviewed shone through every oral history, creating positive experiences for all.

However, approaching these interviews with two interviewers has challenged me as an oral historian. Typically, it is the job of one interviewer to direct an oral history and help guide narrators through the discussion. I.e. Should I ask a follow-up question here or move on? How much time should we spend on this one topic? But working with two interviewers means I am not the sole person in control of the oral history, even when working off the same interview outline. At any given time, one interviewer might want to leave a topic, while another wants to ask more questions.

In order to alleviate some of this confusion, Cooks and I have had to not only build rapport with narrators, but also with each other. And after conducting several interviews together, we have worked out our own system of how to communicate during oral histories – non verbally or with sticky notes – and in how to collaborate in preparing interview outlines. For instance, before I approached a narrator for a pre-interview conversation, Cooks and I had conversations about why the individual was chosen to participate in the project, what themes we hoped to address in the oral history, and what resources I as the non-expert should consult. After completing the pre-interview with the narrator, I used that discussion to build out the interview outline, which I shared with Cooks. We used a Google Docs file to have a back-and-forth about interview structure, language to use, and even subjects to avoid or emphasize. As we decided Cooks should take the lead in these oral histories, this early collaboration was key to their success.

While working on the GRI’s African American Art History Initiative, I have also been challenged to better center the underrepresented voices in these oral histories. In a project that in part seeks to investigate race and power in the art world, this was especially important for me to get right. After all, I’m a white woman who works for an elite university – UC Berkeley – and such institutions have sometimes silenced the contributions of African Americans. In order to combat this historical power dynamic, I privileged extensive pre-interview conversations with narrators about what they wanted to discuss, including the potential to break from the way art historians, critics, or journalists have previously interpreted their lives or work. This is a meaningful practice for any oral history, but these interviews taught me to be acutely sensitive in helping individuals narrate their life stories in the ways that they prefer.

Navigating all these issues in interviews from both subject areas in the Getty Trust Project has challenged me to be a better and more flexible interviewer, and to appreciate the humility required along the way. I hope you enjoy learning from the interviews in this project as much as I have!

Here some finalized Getty Trust interviews I have conducted over the last year:

Here are some other Getty Trust interviews I have conducted that you can to look forward to in the coming months:

David Driskell

Charles Gaines

Thomas Kren

Joyce Hill Stoner

Other non-Getty interviews I’ve conducted in the past year:

Mary Hughes- Bay Area Women in Politics

Zachary Wasserman- Law and Jurisprudence Individual Interviews

Howardena Pindell: Artist, Teacher, and Social Observer

Howardena Pindell is a painter and mixed media artist, as well as a professor at State University of New York at Stony Brook. She earned a BFA from Boston University in 1965 and an MFA from Yale University in 1967. Pindell worked at the Museum of Modern Art from 1967 to 1979, where she held several positions, including exhibit assistant, curatorial assistant, and associate curator. She cofounded the A.I.R. Gallery in 1972. Pindell has taught in the Department of Art at State University of New York at Stony Brook since 1979.

Pindell’s interview is the first in a series of oral histories with prominent African American artists for the Getty Research Institute’s (GRI) African American Art History Initiative. These oral histories complement the GRI’s ongoing work to collect, preserve, and interpret the art and legacies of these artists.

Pindell was born in 1943 and grew up in segregated Philadelphia. Thanks to the support of her parents and her demonstrable talent, Pindell had a great deal of exposure to art early in life. She went on to study at Boston University and Yale University, then moved to New York in the 1960s. In New York Pindell began working at the Museum of Modern Art while also continuing to paint. She recalled, “…I was working five days a week, and I was used to having natural light, and I didn’t have natural light.” As natural light is so important to a painter, and her work schedule cut into daylight hours, Pindell started experimenting with mixed media in these years – a practice she has continued to expand.

Perhaps Pindell’s best-known work is Free, White and 21, a video performance piece from 1980 that is a commentary on her experiences with racism and sexism. Listen to Pindell recount the logistics of creating the piece.

Free, White and 21 also relates to many of Pindell’s ongoing challenges with racism in the women’s movement and the art world at large. Though she was a cofounder of A.I.R. Gallery in 1972 – the first artist-run gallery for women in the United States – as an African American woman, she often felt marginalized in discussions about how to expand opportunities for women artists.

Pindell also spoke at length about her work as a professor of art, and her approach to teaching. Having been academically trained, she worked with many different professors and knew what teaching styles she would and would not emulate. Further, she saw working with students as important to her practice as a working artist. Pindell explained, “I think teaching helps me a lot, just so it keeps me fresh, because I can help the younger students – and in some cases, older students – with their work with formal issues. That keeps me informed about how I should think about my work, as well.”

Pindell’s story highlights the challenges of being a working artist, the importance of teaching others, fighting racism and sexism in the art world and beyond, as well as the long-overdue recognition of African American artists.

To learn more about Howardena Pindell’s life and work, check out her oral history!

Kathleen Dardes and the Global Impact of the Getty Conservation Institute

The Getty Oral History Project includes interviews with individuals across the spectrum of the Getty Trust, including the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), which does international work to advance the field of art conservation. Of the four programs in the Getty Trust, the GCI stands out both for its scientific collaboration with other Getty entities, and its dedication to sharing conservation information worldwide. Kathleen Dardes’ lengthy career working in various GCI training programs is emblematic of this mission.

Kathleen Dardes is the head of Collections at the Getty Conservation Institute. She studied art history and classics at Temple University in the 1970s, and then went on to study art conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the 1980s, specializing in textile conservation. Dardes then worked as a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She joined the GCI in 1988 as the senior coordinator for the Training Program.

When Dardes joined the GCI in 1988, this Getty program was only three years old and trying to establish itself in the field. Dardes recalls working to build credibility as an international art conservation organization, and struggling against “skepticism” about this new Getty entity:

“I think part of it had to do with the fact that we were so darn rich, and we could buy pretty much anything we wanted and could do anything we wanted, and we weren’t beholden to anyone except our trustees. That gave us a certain freedom, which I think was sometimes resented in the broader field. So we had to prove ourselves.”

Part of the way the GCI proved itself was investing heavily in the international training programs Dardes helped create to share conservation best practices worldwide. These included the idea of preventive conservation, or delaying the deterioration of objects through procedures like managing collections environments. Dardes explained the need for this training, saying,

“In the field, you’d hear these funny stories about people making all sorts of elaborate measures to control environments in a gallery space or storage area, but the roof was leaking [laughs] or there was a pest issue or something. So we were looking at the small details, and not the larger system that the museum is.”

In recent years, the GCI has undertaken a project called MEPPI or Middle East Photograph Preservation Initiative. Dardes explained that the GCI and several partners worked hard to establish much-needed photograph preservation courses throughout the Middle East to help institutions protect these collections. This project included many challenges, not the least of which is political instability. In her interview Dardes shared the inspirational story of one MEPPI participant’s dedication to conservation, even in the midst of the Syrian Civil War:

“When we arranged a follow-up course in Lebanon, which was open to people from throughout the region, one of the participants in Syria, at great personal risk, got on a bus with her father, who was there to protect her, and took a bus from Syria to Beirut. Took her two days to do that, a trip that normally takes half a day. Couldn’t fly because it was too difficult to go to the airport, too risky, but came to Beirut to be with her old colleagues and take a course—which we all found absolutely stunning. But that’s how committed she was, not only to the course itself, to the collections she was in charge of, but also to the network that was forming. She wanted to see her old colleagues and be involved in this thing called MEPPI. So it sounds very pollyannaish, but it was a wonderful thing. People who don’t often have the opportunity to be involved in projects like this don’t take them for granted. It was something that we all thought was remarkable.”

Though she has not explicitly used her skills as a textile conservator while at the GCI, Dardes has found opportunities to engage with the larger implications of cultural heritage around the world. Indeed, being a part of the Getty Trust has opened global opportunities for her—and the GCI—to share and teach conservation best practices on an incredible scale.

To learn more about her work with the Getty Conservation Institute, check out Kathleen Dardes’ oral history!