Tag: Digital Collections Unit

530K Primary Resources Now Available Online through The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive

The Bancroft Library has recently completed the digitization of nearly 150,000 items related to the confinement of Japanese Americans during World War II as part of a two-year effort to select, prepare, and digitize these primary source records as part of a grant supported by the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. This program helps to support the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. This recent project, The Japanese American Internment Sites: A Digital Archive, represents our fourth grant from this program, which together have culminated in over 530,000 primary resource materials being made available online.

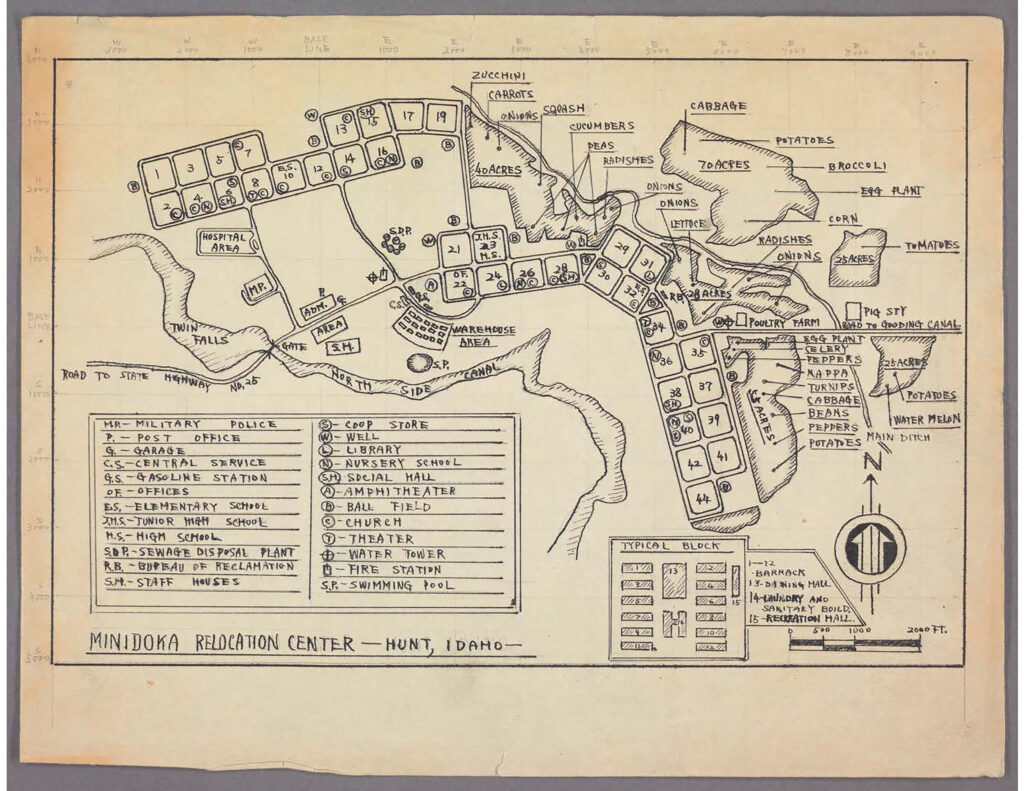

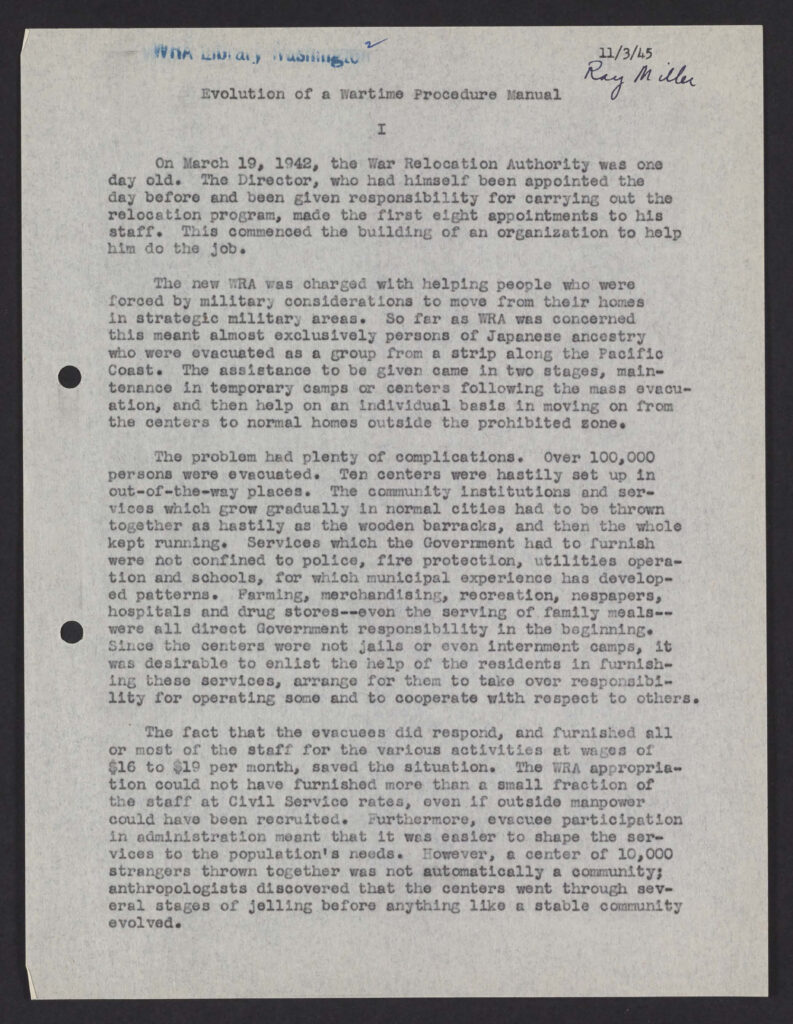

The project focused on the U.S. War Relocation Authority (WRA) files from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (BANC MSS 67/14 c). The WRA was created in 1942 to assume jurisdiction over the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war. Between 1942-1946, the agency managed the relocation centers, administered an extensive resettlement program, and oversaw the details of the registration and segregation programs. These newly digitized records from the Washington Office headquarters and the district, field, and regional offices, formally document WRA management of internment of Japanese Americans in “relocation” centers and resettlement of approved individuals under supervision in the eastern states. Digitized materials document the registration of individuals; disturbances such as strikes; policies and attitudes; daily life in the camps including educational and employment programs; correspondences and other writings by evacuees; Japanese American service in the armed forces; and public opinion.

Since 2011, the Bancroft has been awarded four grants from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The previous grants have digitized records from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study and archival collections selected from individual internee’s personal papers, photographs, maps, artworks, and audiovisual materials. The Bancroft’s Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive website (http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/jacs) brings together all the digitized content and the recently published LibGuide (https://guides.lible.berkeley.edu/internment) that explains how to use and access these collection resources.

As we now embark on our recently awarded fifth grant from this program, we look forward to bringing even more collections online to support researcher access. We are honored and grateful to be able to make these important resources available to help interpret this period in American history and to preserve them for future generations.

The project was led by digital project archivist Lucy Hernandez and principal investigator Mary Elings, Assistant Director of Bancroft and Head of Technical Services. Special thanks to Julie Musson, digital collections archivist at Bancroft and Jennafer Prongos, BackStage Library Works technician for their work on this project, as well as support from Theresa Salazar, Bancroft curator of Western Americana. Many thanks to the Library Information Technology group at the University Library for their work in managing the files, maintaining the information systems used in the project, and ensuring the publication and long term preservation of the digitized collections through our partnership with the California Digital Library.

————

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

How we’ve come to Bridge the Gap

by Sonia Kahn from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

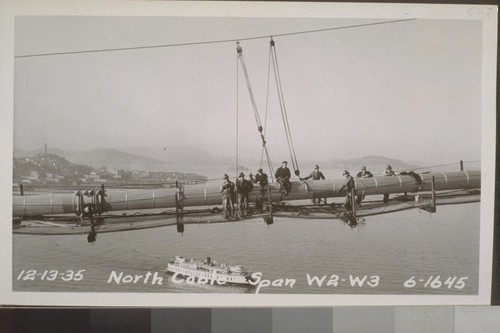

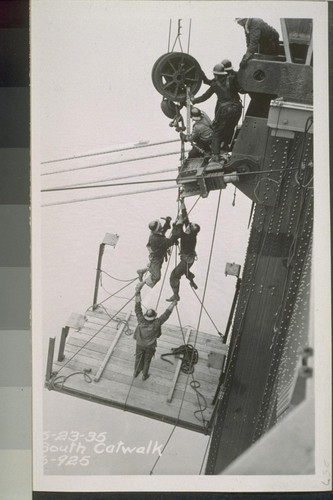

Today the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, known to locals as just the Bay Bridge, is an essential part of many Bay Area commuters’ daily routine, but a mere 80 years ago the bridge many now take for granted as just one more part of their traffic-filled commute did not exist. On November 12, 2016, the Bay Bridge celebrated its 80th birthday, having officially opened to the public on that date in 1936. Today the Bay Bridge is oft overshadowed by its 6 month younger brother, the Golden Gate Bridge, as an iconic sign of San Francisco. But since the 1930s the Bay Bridge has played an essential role in bridging the gap between the East Bay and San Francisco.

It’s impossible. That was what many critics charged at those who explained they wanted to build a bridge across the San Francisco Bay. The idea to construct a bridge connecting Oakland to San Francisco had been around since the 1870s but saw no real progress until the administration of President Herbert Hoover, when the Reconstruction Finance Corporation agreed to purchase bonds to help fund construction which were to be paid back with tolls. But was building such a bridge really possible? In some places, the Bay was more than 100 feet deep, and on top of that, construction would have to take into consideration the threat of an earthquake. Interestingly, engineers planning for the bridge were more concerned with the threat brought about by high winds which could affect the bridge’s integrity.

Ground was broken for the bridge on July 9, 1933, and was welcomed with celebration. The United States Navy Band played at the event, and an air acrobatic left a trail of smoke between Oakland and Rincon Hill where the bridge would connect the East Bay to San Francisco. Celebration was well warranted. The feat of engineering was constructed in just three years, sixth months ahead of schedule! At a total cost of $77 million, the Bay Bridge was an engineering marvel which spanned more than 10,000 feet and was the longest bridge of its kind when it was completed.

From its opening until 1952, cars were not the only passengers on the Bay Bridge. The two-decker bridge saw cars traveling in both directions up top while trains and trucks traveled in both directions on the lower deck. In 1952 trains were scrapped, and in 1958 the upper deck was reconfigured to handle five lanes of westbound traffic as the lower deck accepted passengers headed for Oakland.

Since the 1950s the Bay Bridge has seen many developments. HOV lanes were added for high-occupancy vehicles, and the 1970s saw a decrease and eventual elimination of tolls for these vehicles. A metering system to regulate vehicles entering the bridge was also added which reduced traffic accidents by 15%. In 1989, the infamous Loma Prieta earthquake caused a portion of the upper deck of the Bay Bridge’s eastern span to collapse, proving that the structure was still susceptible to particularly strong tremors despite its strong moorings. This led to retrofitting procedures on the bridge. Most recently a new eastern span was built and was opened to the public in September 2013 after a decade of construction.

Today the Bay Bridge sees more than 102 million vehicles a year cross its decks, more than 11 times the number it carried in its first year. So perhaps next time you cross the Bay Bridge take a minute to appreciate the 80-year-old engineering marvel that makes crossing the Bay a breeze-if you don’t get stuck in the Bay Area traffic!

The Bancroft Library maintains a collection of over 1,100 photographs from the construction of the Bay Bridge.

View the collection: Construction Photographs of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge (BANC PIC 1905.14235-14250–PIC)