Tag: American history

Primary Sources: Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movements

The Library has invested in the creation of Reveal Digital’s Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movement and now has access to the first batch of digitized content on the JSTOR platform. The following information about the collection was shared in Reveal Digital’s announcement:

Covering primarily the 1950s and 1960s, Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movements provides access to primary source documents that focus on how ordinary citizens in the smaller communities viewed, participated in and lived through this historical era. When completed in 2025, the collection will include letters, general correspondence, logs, demonstration plan outlines, transportation logs and plans, meetings, worship services, photographs, newsletters, news reels, interviews and musical recordings from Black, Latine, Native American and Asian American Pacific Islander communities.

The eight compilations from the Atlanta History Center include:

- Alert Americans Association broadside “Martin Luther King…At Communist Training School”

- Atlanta American Council of Christian Churches documents on the Black Manifesto

- Clarence Bacote papers

- Coretta Scott King documents

- Herman L. Turner papers

- Jones family papers of Lovett School

- Roland M. Frye papers

- Southern Regional Council documents

A link to this collection can be found in the History: America guide under Parimary Sources by Topic > Civil Rights and in the Library’s A-Z Database list.

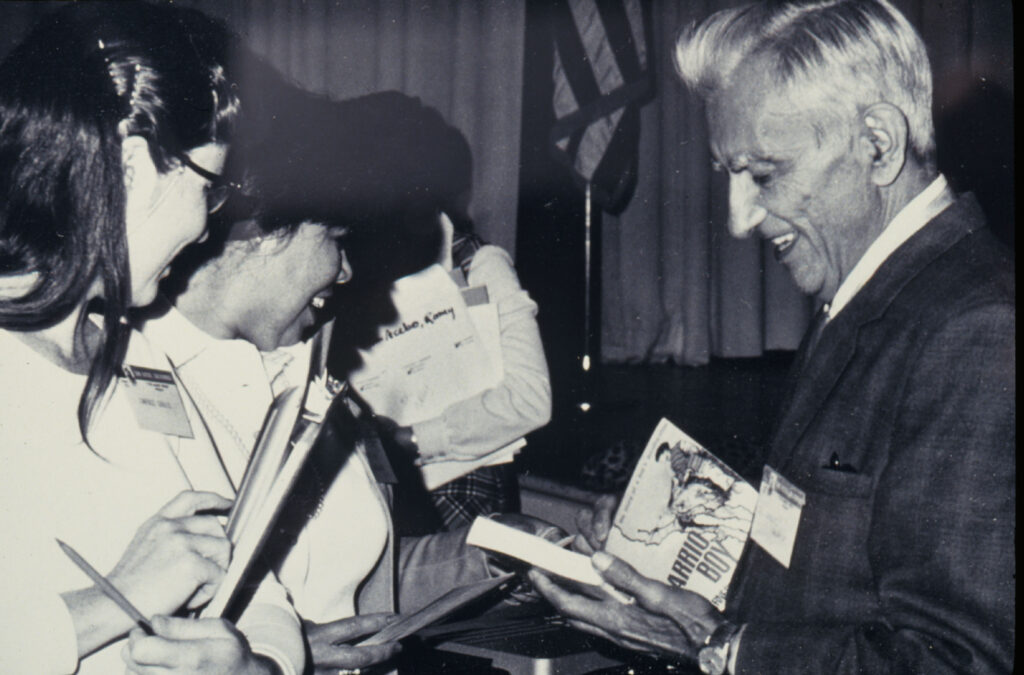

A spearhead for the barrio: the educational activism of Ernesto Galarza

From the Archives

By Adam Hagen

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center houses a number of oral histories that center the lives of Mexican American activists. One such history, Burning Light: Action and Organizing in the Mexican Community in California, contains the recorded speeches and interviews of Ernesto Galarza from the late 1950s through the early 1980s, and provides a glimpse into the life of a man whose commitment to the Mexican American agricultural workers of California never wavered, even when he found himself a continent apart from them.

Galarza’s words, which he imbues with a certain dry poetry, recount a life of extraordinary experience and achievement: Galarza worked as an organizer with the United Farm Workers of America, where he was instrumental in bringing the bracero program to an end; as an educator at the elementary and collegiate levels; and for a time as the chairman of the development of bilingual educational material for the National Committee of Classroom Teachers. He also worked as a consultant for several organizations and institutions, including the government of Bolivia. A recurring theme in Galarza’s oral history, and the subject of this profile, is his efforts on behalf of bilingual education and Spanish literacy advancement in the Mexican American community.

Galarza was born in the village of Jalcocotán in the Mexican state of Nayarit in 1905. But fleeing the tumult of Francisco Madero’s revolution, he and his family came to Sacramento in 1911, when the Central Valley’s patchwork of farm property was not yet its present expanse and its limits did not so easily elude the eye. There, enveloped in a community of agricultural laborers in the Sacramento barrio, a young Galarza would see firsthand the struggles of Mexican Americans and braceros as they tried to navigate the foreign land in which they now found themselves. And, as his family was of modest means—exacerbated by his mother’s death in 1917—he too joined in this work from an early age. One of the recorded talks compiled in the oral history contains a poignant allusion to his communities’ challenges in adapting to life in the United States, and, as it deals with the matter of English language acquisition, reveals the seeds of his future work. In the talk, Galarza recalls that he “became a leader in the Mexican community at the age of eight for the simple reason that I knew perhaps two dozen words of English.”

English proficiency, however, was only one of a number of skills that Galarza exhibited in his youth. His academic prowess was so apparent that Sacramento High School teacher Ralph Everett approached him personally and asked that he reconsider his plan to work at the Sacramento Libby, McNeill & Libby cannery after graduation, insisting that he attend college instead. Everett even went to great lengths to help Galarza gain admission to Occidental College in Los Angeles, the institution he would graduate from in 1927. After Occidental, Galarza would go on to earn a master’s degree in history from Stanford University in 1929 and a doctorate in sociology from Columbia University in 1944.

Galarza’s recollection of his time at these institutions reveals how rare it was for a “Mexicano” to have the opportunity to obtain a higher education in the early twentieth century. He had this to say at a talk for Chicano studies students at UC Berkeley in 1977:

The Chicano students that I knew in the thirties at Columbia and elsewhere were very few in number. At Columbia University I didn’t know another graduate student in the department of history or political science or public law, which is where I did my work. Neither were there many of us in the undergraduate institutions in Southern California where I went to college at Occidental. I remember, I think it was in 1925, out of sheer curiosity I inquired among my friends at UCLA, USC, Pomona, Whittier and all of that cluster of colleges in the south, and I could only identify six of us in all of those places. Of course, possibly that wasn’t a good count because even then there were some Chicanos who had already given up their identity. They had become anything but Mexicans. In those days, we didn’t talk about Chicanos. You were either a Mexicano or you were not.

His skills in English and consequent academic achievements were a relative anomaly among the bracero and Mexican American communities due to there being a dearth of bilingual and English language education resources at the time of his youth. According to Galarza, not until the latter half of the twentieth century did the federal government take the concept of bilingual education and English as a second language (ESL) education seriously and fund it in any substantial fashion. And, as he notes in his oral history, once funding did increase there remained a system that overlooked the intricacies of bilingual education; advisory committees in Washington attempted to regulate the bilingual and ESL instruction from afar, and their distance resulted in curriculum that was incongruent with students’ needs.

Concerned about this oversight, Galarza explains that he and other instructors working in bilingual education were actively challenging the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and the Office of Bilingual Education in the 1970s, and had begun to see success. As he says in the oral history, he felt their work “has been so effective, even modest as it is, that it has created waves that have become very ominous to them.”

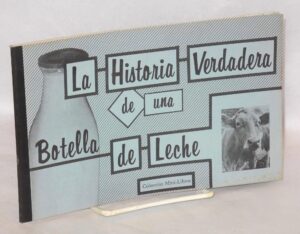

And beyond his pushing for better, more personalized bilingual education curriculum on an institutional level, Galarza—believing that Spanish literacy had to precede English instruction—took it upon himself to craft and publish what he called “Mini-Libros,” easy-to-read Spanish texts that he designed for use in the classroom and hoped would engage young readers. So as to make students as comfortable as possible, the Mini-Libros even contained vocabulary specific to Mexico and the working-class immigrants coming to the United States at the time.

These actions were especially timely because Mexican immigration into the US was greatly increasing in the 1960s and ’70s, a topic thoroughly discussed in the interview. Galarza recognized the wealth of challenges—from housing to employment to education—that came with incorporating such a massive population into the fabric of American society, and identified the issues of literacy and English proficiency as those he was most eager to help resolve.

Each summer in his undergraduate years Galarzo would return to Sacramento to do what he called “bread and butter work” in the farms and the cannery. Later, when he left California to study at Columbia and the path home was no longer so easily negotiated, his community’s want of literacy became a major concern, in part his due to its personal impact:

I began to be disturbed by the lack of news from home. My family and my friends back in Sacramento were not writers. They didn’t know, many of them, how to write…When I realized after my third or fourth year back in the East that this was happening to me, I became very disturbed. And while we stayed in the East another six years, that feeling never left me that what was happening back in California in all the towns that I knew and where I had worked, I was not keeping abreast of.

Galarza believed that the Mexican immigrant children coming into the school system in the mid-twentieth century had to be brought into the fold of American life, to be “acculturated,” in his words, so as to avoid the fate of his own family and community. And such acculturation could not begin with a hard-and-fast imposition of English instruction, something he believed would only further alienate the newly arrived immigrants, accelerate the creation of insular communities, and complicate their path to prosperity in the US. He viewed bilingual education as the obvious answer to this challenge. It would help a child, as he noted in his oral history, to “recognize—to get into—and become familiar with this strange environment into which he’s been dropped.”

Galarza’s oral history is an invaluable glimpse into the subtle divides of his time: for each acknowledgement of how badly the “American hosts” have treated Mexican Americans, he has another remark on the myopia of Mexican American activists due to their protests against acculturation—something he believed was “largely for the purposes of propaganda.” And beyond these commentaries, he proves to be equally invaluable as a representation of a steadfast activism that lacks glamour and prefers actions to words. Galarza identified the challenges of his time and repeatedly asked the central question: what to do about it?

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

Adam Hagen recently graduated UC Berkeley with majors in Spanish linguistics and history. Adam worked as a student editor for the Oral History Center and was also a member of the editing staff of Clio’s Scroll, the Berkeley Undergraduate History Journal.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has more than thirty holdings by Ernesto Galarza, including poems, books, reports, pamphlets, conference proceedings, and audio of talks and panel discussions. From the UC Library Search, go to “Advanced Search,” select “UC Berkeley special collections and archives,” and in the search field, enter Ernesto Galarza.

The Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project provides a rare, firsthand look at the development of the field of Chicana/o studies over the last fifty years, as well as unique insight into the lives and careers of the pioneering scholars who shaped it.

The Oral History Center digital collection contains additional oral histories of Mexican American activists, such as Hope Mendoza Schechter and Herman E. Gallegos. More can be found by searching “Mexican American community” or “Mexican American activism” on the Oral History Center home page.

Ernesto Galarza’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s Advocacy and Philanthropy—Individual Interviews collection. Read more about the collection in the article by Lauren Sheehan-Clark, “Helping Hands: A Guide to the Oral History Center’s Advocacy and Philanthropy Individual Interviews.”

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Primary Sources: Propaganda collections

The Library recently acquired three collections of propaganda materials: two from World War II a collection of anti-Semitic materials published before the war.

This publication collection consists of over 1,000 air dropped and shelled leaflets and periodicals created and disseminated during the Second World War. The majority of items in this collection were printed by the Allies then air or container dropped, or fired by artillery shell over German occupied territory. Many leaflets and periodicals have original publication codes and were printed in over 10 languages. Only shelled leaflets, Germans to Allies (115 items), are in English.

Allied Propaganda in World War II and the British Political Warfare Executive

This collection presents the complete files of the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) kept at the U.K. National Archives as FO 898 from its instigation to closure in 1946, along with the secret minutes of the special 1944 War Cabinet Committee “Breaking the German Will to Resist.”

German Anti-Semitic Propaganda, 1909-1941

Comprised of 170 German-language books and pamphlets, this collection presents anti-Semitism as an issue in politics, economics, religion, and education. Most of the writings date from the 1920s and 1930s and many are directly connected with Nazi groups. The works are principally anti-Semitic, but include writings on other groups as well, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Jesuits, and the Freemasons.

Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley

By William Cooke

The last fifty years might be considered the modern era of intercollegiate athletics management in the United States. Ballooning TV contracts and Title IX have changed the college athletics landscape forever. The growing pains associated with those changes were felt by everyone involved with college sports, including those at UC Berkeley. The Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960–2014, offers cross-sections of the Cal Athletics world during those formative years in the form of interviews with key internal and external actors.

For college sports fans, the history of the management of collegiate athletics at UC Berkeley is a familiar one. The unending conflict between maintaining a solid academic reputation and fostering winning programs, funding dilemmas, NCAA sanctions and the challenges surrounding gender inclusion in sports — common issues for every university athletic department — are all included in UC Berkeley’s storied athletics history.

These tensions and developments are reflected in the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960–2014. Interviews between former UC Berkeley Associate Chancellor John Cummins — who served as interviewer — and a diverse cross sampling of individuals involved in the management of intercollegiate athletics, including athletic directors, chancellors, donors, and senior administrators, make up this collection of 45 publicly released interviews.

Organized by decade, here are a few snippets of the voices represented in this collection of oral histories. Themes in this collection include but are not limited to funding dilemmas, controversies surrounding academic standards for student-athletes, the evolving relationship between women’s and men’s sports, and the sometimes incompatible interests of athletic boosters and University officials.

The 1970s: The beginning of the modern era — Dave Maggard and Luella Lilly

The 40s and 50s were the golden years of Cal football and basketball. Led by legendary head coach Lynn “Pappy” Waldorf, Cal’s football program made three Rose Bowl appearances between 1948 and 1950. In 1959, head basketball coach Pete Newell led Cal to the program’s lone national championship to date.

A relatively disappointing decade followed for both programs. Then, in the early 1970s, catastrophe. When the NCAA found out that football and track athlete Isaac Curtis had failed to take the SAT as required, the intercollegiate governing body came down hard with sanctions.

Dave Maggard, who was appointed Athletic Director in 1972, argued against those in the administration and around Cal Athletics who wanted to fight the sanctions. These included the Golden Bear Athletic Association, an independent booster organization that had sued the NCAA in response to the sanctions. According to Maggard in his oral history:

When I became the athletic director I went to the administration and said, “This is a huge mistake. You cannot fight these people. We need to work to get on the inside, we need to get on committees, we need to be a part of the NCAA. I will tell you that they will rip this place apart, and this is something that you will never win. You will never win.”

The sanctions included probation and four years of bowl game ineligibility, a blow to the revenue stream of Cal’s most profitable program. Thanks to Maggard’s cooperation with the NCAA, though, the sanctions were eventually lifted.

At the same time, intercollegiate athletics at UC Berkeley took a huge step towards achieving gender equity in sports at the University. Following the passage of Title IX in 1972, the University hired its first director of Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics, Luella “Lue” Lilly.

Generating revenue for women’s athletics was a difficult undertaking. But Lilly made it a priority and found creative ways to raise funds and boost support for the newly established programs. Those efforts included the recruitment of a local politician and an Olympic gold medalist.

Then one time when we had— Dianne Feinstein and Ann Curtis were going to help us with the Mercedes raffle that we were giving out… We went over in front of city hall, and we just drove. We looked to see what was going to make the best picture, and there was a fountain behind it. We just drove the thing right up on the sidewalk.

If the 1970s was an era of immense change in athletics management at UC Berkeley, the next two decades would see the University settle its position on the relative importance of athletics and academics.

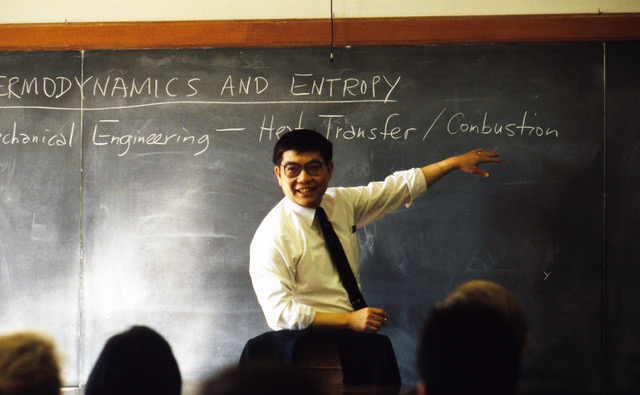

The 1980s and 1990s: The balance between school and sports — Chancellors Ira Michael Heyman, Chang-Lin Tien

When Chancellor Ira Michael Heyman took the reins from Albert Bowker in 1980, he inherited a sound athletics fundraising plan that Maggard had developed the decade prior. In many ways, Heyman supported the success of athletics at Cal, going so far as to allow “Blue Chip Admits” — 20 student athletes per year who would not normally be eligible to attend UC Berkeley.

But even while supporting athletic success at the calculated expense of lower academic standards, Heyman did not avoid criticism from UC Berkeley athletics boosters:

So they [The Grid Club] kept pushing me. “How important is athletics to you in relation to academics?” et cetera, et cetera. And I essentially said, “Academics, they’re really important. And intercollegiate athletics are of importance.” I just tried to make that distinction. And they said, “Well, on an index of one to ten where do athletics stand?” And I said, “Oh, about seven. Six and a half or seven.” That group never really warmed up to me.

In the early 1990s, Earl “Budd” Cheit, who served as the dean of the Haas School of Business, Executive Vice Chancellor and Interim Athletic Director over the course of his time at UC Berkeley, found himself right in the middle of that ongoing tension between winning and maintaining the University’s reputation for being first and foremost an elite academic institution.

Head football coach Bruce Snyder had led the Bears to a 10-2 season and a trip to the Citrus Bowl in 1991. Arizona State University doubled UC Berkeley’s annual salary offer of $250,000 to recruit Snyder.

Long-time supporter of UC Berkeley athletics Walter “Wally” Haas offered to match ASU’s offer along with the help of other boosters. But when Cheit relayed Haas’s message to Chancellor Chang-Lin Tien, the Chancellor shot the idea down and explained his reasoning.

Wally Haas called me during this time, and he said, “There are a number of people, myself included, who will come up with the money to match what he’s being offered. Will the Chancellor go for that?” And I called Chang-Lin and talked to him. And Chang-Lin said, “I can’t justify paying a coach that much more than the highest-paid professor on the campus.”

The 21st century: Changing priorities — Robert Berdahl, Robert Birgeneau

The 80s and 90s saw proponents of academic integrity and responsible spending win out over those who wanted Cal Athletics to accept the national shift toward a culture of commercialism in intercollegiate sports. The potential to rake in huge revenues from TV deals by investing in “revenue athletes” — student-athletes on the football and men’s basketball teams — drove the impetus to sacrifice academic standards for athletic success.

The hiring of Athletic Director Steven Gladstone in 2001 marked the beginning of a short, half-hearted effort to spend money in order to make money. Under Gladstone’s direction, coaching and administrative salaries were increased to attract and retain the very best in the intercollegiate athletics industry, all in the hope of making the two revenue sports — Cal football and men’s basketball — into elite college programs.

But with higher spending came concerns about the growing athletics budget deficit, which was compounded by the ever-growing cost of the newly built Haas Pavilion. In his interview with Cummins, Robert Berdahl, UC Berkeley’s Chancellor between 1997 and 2004, attributes some of the blame for deficit spending on the 1991 Smelser Report, which called for broad-based, highly competitive athletic programs in spite of budget constraints.

I think that the Smelser Report was a real disservice, because it created in the donor and booster community the notion we’re going to be as excellent in athletics as we are in academics, which I think is an unrealistic expectation for any high-quality university. I don’t think there’s any university of high quality that has that aspiration. Maybe Stanford, maybe Stanford’s the only one that does… But they don’t—they are competitive in football and basketball but rarely go to the Rose Bowl or to the NCAA championship.

Robert Birgeneau, who succeeded Berdahl as Chancellor, saw to it that priorities change under his leadership. To the dismay of some donors, Birgeneau replaced Gladstone with Athletic Director Sandy Barbour in 2004. During her tenure, Barbour facilitated the creation of the University Athletics Board (UAB), a committee that included faculty members and student athletes. Its purpose was to increase transparency in athletics spending by sharing this information with faculty for the very first time.

The Great Recession of 2008 made budget constraints even tighter. In 2010, Birgeneau made the difficult and controversial decision to cut four athletics programs — baseball, men’s and women’s gymnastics, and women’s lacrosse — and make rugby a club sport.

Because we had such loyal supporters of [Division] IA sports, I felt that they needed to know that the financial situation really was quite dire and that we needed them to step up, both themselves personally and to organize fundraising campaigns. As I said, that just simply did not happen… So, in this fateful September meeting, after the cold hard financial facts were presented to me, I agreed with the financial and IA people, that there really was not any choice. Specifically, we were never going to be able to achieve our goal of $5-million-a-year support from the campus without eliminating sports.

Supporters of those four sports eventually raised a combined $20 million in order to restore them to Division I status.

We worked out a compromise, basically asking each sport to raise enough funds to close their operating gaps for the next five to seven years… The baseball supporters raised nearly $10 million in six weeks. It is notable that philanthropy to baseball had been negligible for many, many years, and so there was a qualitative change. Indeed, this funding crisis brought the baseball community together, and in fact has resulted in us now having a stadium with lights at night. Thus, for baseball the situation actually is markedly improved.

These quotes represent just a small fraction of what this collection has to offer. Researchers will also find information on intra-departmental relationships, the personal experiences of former administrators in regards to particular decisions, and the retrospective opinions of both external and internal actors in the most crucial formative decades in the history of intercollegiate athletics management, both at UC Berkeley and institutions across the country.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

In addition to these oral histories, The Bancroft Library has related sources on Cal Athletics and intercollegiate athletics management more generally, including books on athletics facilities and fundraising, department records, and newspaper articles.

Read “Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond,” also by William Cooke.

Related oral histories include Brutus Hamilton, Student athletics and the voluntary discipline : oral history transcript / and related material, 1966-1967 and Peter F. Newell, UC Berkeley athletics and a life in basketball.

66 years on the California gridiron, 1882-1948; the history of football at the University of California. Brodie, S. Dan. 1949. Bancroft BANC F870.A96 B7

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. Compiled by Kevin Lilley, Lisa Iancin, and Chris Downey. UC Archives Folio ; 308m.p415.c.2001.

Pamphlets on athletics in California. Bancroft Pamphlet Double Folio ; pff F870.A96 P16.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

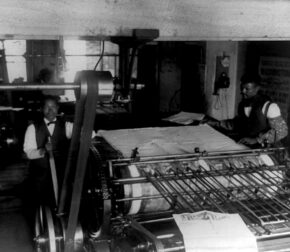

Primary Sources: African American Newspapers in the South, 1870-1926

African American Newspapers in the South, 1870-1926 is a new addition to Accessible Archives. It documents the African American press in the South from Reconstruction through the Jim Crow period. Written by African Americans for African Americans, the first-hand reporting, editorials, and features kept readers abreast of current domestic and international events, often focusing on racial issues. The editors didn’t shy away from exposing racial discrimination and violence, including the emotionally laden topic of lynching. Yet, the newspapers also covered lighter fare, reporting on civic and religious events, politics, foreign affairs, local gossip, and more.

African American Newspapers in the South, 1870-1926 is a new addition to Accessible Archives. It documents the African American press in the South from Reconstruction through the Jim Crow period. Written by African Americans for African Americans, the first-hand reporting, editorials, and features kept readers abreast of current domestic and international events, often focusing on racial issues. The editors didn’t shy away from exposing racial discrimination and violence, including the emotionally laden topic of lynching. Yet, the newspapers also covered lighter fare, reporting on civic and religious events, politics, foreign affairs, local gossip, and more.

It includes all complete runs of representative newspapers from the District of Columbia, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and West Virginia:

Athens Republique, 1921 – 1926

The Banner-Enterprise, 1883 – 1884

The Bee, 1882 – 1884

The Black Dispatch, 1917 – 1922

The Educator, 1874 – 1875

The Langston City Herald, 1892 – 1900

The Louisianian, 1870 – 1871

The Nashville Globe, 1907 – 1918

The National Forum, 1910

Pioneer Press, 1911 – 1917

The Republican, 1873 – 1875

Semi-Weekly Louisianian, 1871 – 1872

The Tulsa Star, 1913 –1921

Western World, 1903 – 1904

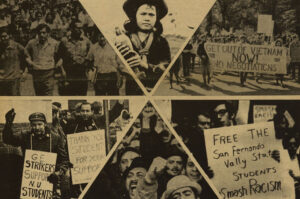

Primary Sources: Student Activism

Reveal Digital’s Student Activism collection aims to provide access to unique, yet essential, primary sources documenting the deep and broad history of student organizing in the United States. It is intended to serve as a scholarly bridge from the extensive history of student protest in the United States to the study of today’s vibrant, continually unfolding actions.

Reveal Digital’s Student Activism collection aims to provide access to unique, yet essential, primary sources documenting the deep and broad history of student organizing in the United States. It is intended to serve as a scholarly bridge from the extensive history of student protest in the United States to the study of today’s vibrant, continually unfolding actions.

The completed collection will contain approximately 75,000 pages drawn from special collection libraries and archives around the country. Materials intended for inclusion are wide-ranging in nature: Circulars, leaflets, fliers, pamphlets, newsletters, campaign materials, protest literature, clippings, periodicals, bulletins, letters, press releases, ephemera; and meeting, demonstration, conference, and event documentation. Currently approximately 58,000 pages are available.

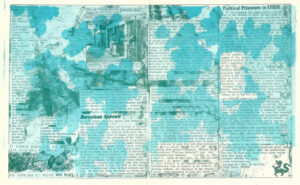

Primary Sources: American Prison Newspapers, 1800-2020: Voices from the Inside

On March 24, 1800, Forlorn Hope became the first newspaper published within a prison by an incarcerated person. In the intervening 200 years, over 450 prison newspapers have been published from U.S. prisons. Some, like the Angolite and the San Quentin News, are still being published today. American Prison Newspapers will bring together hundreds of these periodicals from across the country into one collection that will represent penal institutions of all kinds, with special attention paid to women’s-only institutions.

On March 24, 1800, Forlorn Hope became the first newspaper published within a prison by an incarcerated person. In the intervening 200 years, over 450 prison newspapers have been published from U.S. prisons. Some, like the Angolite and the San Quentin News, are still being published today. American Prison Newspapers will bring together hundreds of these periodicals from across the country into one collection that will represent penal institutions of all kinds, with special attention paid to women’s-only institutions.

Development of the American Prison Newspapers collection began in July 2020 and will continue through 2022, with new content added regularly. The source material for the collection is being provided by numerous libraries and individuals from across the country. Currently there are nearly 100,000 pages available (of a planned 250,000 pages), representing at least one prison in 30 states.

Richard Mendelson, “A Life Lived on the Steep Part of the Learning Curve: Richard Mendelson on Wine Law and History”

by Martin Meeker

Oral History Center Interviewer (retired)

“When we drink a glass of wine, we may enjoy its aromas, consider where it is from, and ideally, care about how it was made and who created it. We might think about the winemaker, along with the vineyard and winery team, and perhaps the brand owner. We most likely don’t consider the people beyond that circle who also play a role in a wine’s existence, ensuring its authenticity, making it more meaningful for consumers, and meanwhile, protecting some of the most sacred places to grow grapes and create wine. For those who are reading this, you are about to meet such a person, one of the most exceptional people in the wine world, and someone who has more passions and layers than the most complex glass of wine you have ever enjoyed,” Linda Reiff, President and CEO of Napa Valley Vintners.

Richard Mendelson is in fact the person about whom Linda Reiff writes, and the Oral History Center is pleased to release this major life history interview with the man. Mendelson is an attorney who has played a pivotal role in creating the field of wine law through his legal practice, historical research and writing, and international leadership on the issue over the past four decades. Moreover, he is a Lecturer in Wine Law at UC Berkeley, School of Law, where he directs the Program on Wine Law and Policy. He also lectures on a variety of vineyard and wine law topics at UC Davis Graduate School of Management and has taught at the University of Aix-Marseille and the University of Bordeaux.

A graduate of Harvard University, Oxford University, and Stanford Law School, Mendelson has handled legal matters involving almost every aspect of the wine business, including liquor licensing, environmental challenges to vineyard development, grape purchase agreements, winery use permits, representation of winery clients before the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control and federal Alcohol & Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, state and federal label approvals, distributor appointments and terminations, and import-export contracts. Mendelson has a special expertise in geographical indications and has been responsible for obtaining recognition for some of the most well-known American Viticultural Areas. He assisted the California legislature with the drafting of legislation to protect the world-famous Napa Valley geographical indication. Subsequently, he successfully defended that law on behalf of the Napa Valley Vintners in the case of Bronco v. Jolly, which he argued before the California Supreme Court. Of his legal work, famed vintner Bill Harlan writes, “His legal mind, business judgment, negotiating skills, discipline, and commitment to his clients are first rate. With great integrity and knowledge and an abiding commitment to be fair and clear, he is able to gain the respect of all parties in practically any setting.”

This oral history is a globe-trotting one, with meaningful stops in England, France, India, and China, but the focus here, as with Mendelson’s work, is California’s Napa Valley. According to Harlan, Mendelson serves “as Napa Valley’s unofficial ambassador, he truly upholds our agricultural heritage and promotes our special place in the world of wine.” Linda Reiff, head of the Napa Valley Vintners, writes, “He helped make Napa Valley one of the most iconic wine regions in the world by mastering groundbreaking initiatives and complex legal challenges. He authors, refines and defends regulations to protect consumers and to ensure a more sustainable wine industry. He is a thinker and a problem solver, a deal maker, a broker.” This oral history goes a long way to explain how over the course of a few short decades “Napa Valley” came to signify and to exemplify environmental stewardship, preservation of agricultural resources, American ingenuity and achievement internationally, and, of course, quality wine.

In this interview, moreover, Mendelson discusses his family’s heritage and his own upbringing in Jacksonville, Florida; his early employment on Capitol Hill; and his attendance at Harvard University, Stanford University, and Oxford University, where he first became enamored with wine in Magdalen College’s wine cellar. Mendelson goes on to discuss his career in wine and wine law, beginning with Bouchard Aîné in Burgundy, France, and continuing in America with the establishment of American Viticultural Areas (AVAs). Other topics discussed in the interview include the research and writing of his books (From Demon to Darling, Law in America: Law and Policy, Spirit in Metal, and Appellation Napa Valley: Building and Protecting an American Treasure), California cannabis law, yoga, tai chi, Hinduism, artistic sculpture and metalwork, and wine law instruction.

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

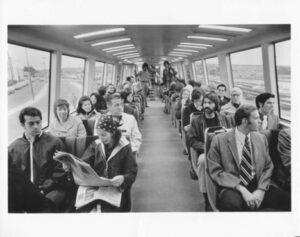

Track changes: how BART altered Bay Area politics

By William Cooke

“It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.” — Mary Ellen Leary, journalist

“The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired.”

— George Christopher, Mayor of San Francisco

On September 11, 1972, an estimated 15,000 people rode Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) on its very first day of operation. The train system, which at that time was a fraction of its current size, has been a vital service to Bay Area commuters for 50 years now. Those with an interest in the history of the Bay Area’s rapid transit system, or regional planning and public transportation more generally, will find a treasure trove of information in the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s (OHC) archive.

But BART’s development is much more than a history of a public planning project. It is also a history of the evolution of government and of local versus regional power sharing. The OHC houses oral histories from big and small players in California’s public administration throughout the entire 20th century. The voices of politicians, journalists, city planners, and others reveal that BART’s development brought about a whole slew of questions regarding the proper role of government at all levels and required a great deal of reciprocity.

Mary Ellen Leary, a journalist who got her start with San Francisco News, studied and wrote extensively about urban planning and development in the early 1950s. In her oral history “A Journalist’s Perspective: Government and Politics in California,” she speaks at length about the origins of BART, and the broader development of regional agencies designed to meet the transportation needs of suburban areas, not just cities. “I felt then and still feel that the degree of local participation generated for BART from the first planning funds to the final bond issue was an extremely interesting and important political development.”

Leary says the impetus to begin work on a regional transit system originated in concerns about traffic congestion in the Bay Area. At the time, however, the idea of an alternative to driving in San Francisco seemed absurd. After all, BART would become the first new regional transit system built in the U.S. in 65 years.

But this worry about compact little San Francisco and the automobile launched this idea about rapid transit. And I laugh now about everybody giving BART such a hard time. It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.

According to Leary, local businessman Cyril Magnin and San Francisco Supervisor Marvin Lewis were among the first to consider the benefits of investing in a public transit system instead of parking garages. Unlike Los Angeles, the Bay Area could not build enough parking lots and garages to meet the needs of a car-reliant city due to limited space. Leary observes:

At any rate, they got a group of some business people to take seriously the idea of “How is San Francisco going to endure the flood of traffic that’s already coming in from the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge? We can’t possibly do it.” The figures were coming out about what percentage of downtown Los Angeles was given over to automobile parking, most of it on the surface. They hadn’t yet begun many multiple-level parking facilities.

Eventually three counties — San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa — committed to the transit system and developed the “BART Composite Report.” This had to be approved by their respective county supervisors in order for a bond measure to be placed on the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District-wide ballot in November of 1962.

In his oral history, longtime Republican politician and former Mayor of San Francisco from 1956–1964, George Christopher, remembers seeking the crucial aye vote of the fifth and still undecided Contra Costa County supervisor, Joe Silva. Silva had been under pressure from his constituents to vote no, because they would not directly benefit from the commuter rail but would bear the high price tag. Without Silva’s vote, the eventual passage of the measure in November and the $792 million bond issue may have been set back by years. According to Christopher, “The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired,” involving a pre-dawn meeting and donuts.

I called him and I said “Supervisor, you’re the important man here. Now what are we going to do about this? All I’m asking is that you put it on the ballot and let the people decide whether they want it or not…. I said, “What time shall we meet?” He said, “Five o’clock in the morning.”… Sure enough we got up at four o’clock in the morning and we went over to Contra Costa County and finally found this restaurant. It turned out to be a little donut shop with no tables, no tables whatever, and we all sat around the counter. Here were all the teamsters, the truck drivers listening to every word we had to say…. I don’t know how many donuts we had, but we certainly filled ourselves.

Many hours and donuts later, Christopher had earned Silva’s crucial “yes” vote in support of the regional rail system. Christopher’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s “Goodwin Knight-Edmund G. ‘Pat’ Brown, Sr. Oral History Series,” which covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966, and is a gold-mine of fascinating anecdotes on city planning and transportation issues during that crucial decade.

Even before the bond issue was put on the ballot and approved in 1962, a consequential battle for regional power over transportation, including BART, was fought, ultimately resulting in a victory for local influence in this regional system. This battle was reflected in the approximately three-year long struggle between the Golden Gate Authority (GGA) and its younger competitor, the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), for control over the planning and operation of transportation infrastructure in the region. Several oral histories from the Oral History Center discuss the importance of ABAG, which refers to itself as “part regional planning agency and part local government service provider.” In the oral history titled “Author, Editor, and Consultant: A Participant from the Institute of Governmental Studies,” Stanley Scott, a research political scientist at UC Berkeley, explains:

It came more from the large business interests, the Bay Area Council, with Edgar Kaiser being the chief proponent and front man, I guess you’d say, to create a Golden Gate Authority. That would incorporate the ports, the airports, and the bridges, the bridges being brought in essentially because they were very profitable organizations. So that one kind of came in, you might say, from the side, but at the same time, also involving regional restructuring.

This really upset the cities and counties, and quite a few others. A lot of people were concerned about it. A lot of people were concerned about just latching on to the bridges and tying them in with the airports and seaports. What are we going to do about all the other transportation problems? There was a great deal of concern.

It also exercised cities and counties that just did not want a major authority coming in from off the wall, so to speak. They began organizing themselves, and that was, in part, the genesis of ABAG. It was not the only reason for ABAG’s creation, but it provided substantial push in that direction. It had a lot to do with it. It scared the local people. That would have been in ’58, ’59, and ’60, that the Golden Gate Authority idea was kicked around. It was over a period of at least two years, and it could have been three, before it finally bit the dust.

T.J. Kent also addresses this theme about local influence and power sharing — with a focus on the role of ABAG — in his oral history, “Professor and Political Activist: A Career in City and Regional Planning in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Kent was a prominent city planner under San Francisco Mayor Roger Lapham in the 1940s, a deputy mayor for development under Mayor John Shelley in the 1960s, served on the Berkeley city council in the 1950s, and was a founder of UC Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning.

According to Kent, former Mayor George Christopher opted to keep San Francisco out of ABAG because he felt that San Francisco was too important a player in the region to enter into an equal-representation regional government. His successor, Mayor John F. Shelley, reversed that policy, bridging the way to cooperation between the Bay Area’s largest city and the influential agency.

Shelley, with the board of supes [supervisors] backing him, he brought San Francisco into ABAG and appointed me as his deputy on the ABAG executive committee. I also served as the mayor’s deputy on the ABAG committee on goals and organization….The Committee prepared the regional home rule bill that was adopted by ABAG in 1966… It called for a limited function, directly elected, metropolitan government. That’s the key report.

Indeed, the publication of the Regional Home Rule and Government of the Bay Area report marked a huge milestone in the actualization of BART. ABAG, which was granted the authority by the State of California in 1966 to receive federal grants, included BART in the four elements of its metropolitan plan. Kent explains:

The first is the central district, enlarged and unified and focused in San Francisco; the second is a regional, peak-hour commuter transit system, which is BART and AC transit, plus the other transit systems serving San Mateo County, San Francisco and Marin and Sonoma counties; third is the open space system, to keep things from sprawling and for basic environmental reasons; and the fourth was comprised of the region’s residential communities, which shouldn’t get too dense, too overbuilt.

ABAG’s ability to receive and use federal money would prove vital to BART’s construction and continued operation. Furthermore, city and county representation on ABAG’s board — as opposed to zero locally elected officials in the defunct Golden Gate Authority — meant that cities likely had more of a say in the planning of BART than they would have had under the administration of the GGA.

Kent, then a Berkeley city councilmember, helped write the ABAG bylaws that balanced regional and local power. Kent believed in the importance of assigning enough power to regional agencies and districts like ABAG and BART, while also maintaining local autonomy. According to Kent — who throughout his oral history stresses the need to protect home rule wherever possible — counties that opted to stay in the Bay Area Rapid Transit District sometimes felt that the District was too restrictive or overbearing. But as a regional representative government with limited authority, conflicts were eventually solved. Kent remembers the back-and-forth between BART and Berkeley prior to the bond issue passing in 1962.

But those [counties] that were left in [the District], there were major battles in the BART legislation because the BART legislation had to give that agency that power and right. I was on the Berkeley council at the time and the battles were serious. There were many things that BART was required to do in consulting the cities and counties before the bond issue was proposed and voted on in 1962 and even after, which I think was good. They required BART to deal with Berkeley as an equal when Berkeley said, “We think—.” Berkeley got tremendous concessions from BART before the bond issue. You may not realize it, but the initial 1956 BART plan for the Berkeley line had it elevated all the way through downtown. Berkeley fought back before the bond issue vote of ʼ62 and got the middle third put underground.

Those counties that decided to stay in the District and cooperate with BART during its construction had a say in the decision-making process. Perhaps due to that fact, the 1962 district-wide bond issue surpassed the required 60% approval threshold, a result that came as a surprise to many political experts. Litigation and negotiations ensued with cities and counties across the Bay Area in the years that followed. But without the initial bond issue, BART could not have even begun construction.

Mary Leary observed that the impetus to create a regional, commuter rapid transit system — as well as the process of planning BART — did much to encourage local participation in politics. Even though ABAG was a regional entity with certain powers over local governments, Leary says that the agency allowed local governments a say in BART’s planning.

I think it was not unrelated that during this same era of local sharing in BART plans on a regional basis the Supervisors Association and the League of California Cities together launched ABAG, Association of Bay Area Governments, a voluntary group of cities and counties to discuss regional problems. It did not become a real regional government. In fact, I always felt it was created by those two groups to thwart moves towards regional government and to make sure cities and counties maintained their own strong voices. But it has been a significant forum and I think cooperation of the various governments around the Bay in planning BART gave it a good start. Interestingly, when planning got underway for where BART’s lines should run and stations should be, this became the first regional planning ever undertaken and local communities could see as some did that they were planning a sewer outfall just where the next-door neighbor town was planning a beach resort, that sort of thing.

In her oral history, Leary also noted a change in public perspective about public transit — away from the idea that no one would visit San Francisco if they couldn’t drive, to voters actually rejecting federal funds for a freeway connecting the Golden Gate and Bay bridges — and the relationship of BART to that.

Anyway, there was a good deal of political pride in the area that they had shared in developing BART from the very start, and it was part of the system’s success. Most other cities sat back and waited for Washington to provide funds for transit. Los Angeles never could get that much regional support. Of course, about that same time San Francisco was so supportive of the transit idea it rejected federal money for a freeway connection between the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge. That really stirred a lot of national attention, saying “no” to millions or maybe billions.

Those interested in exploring the history of BART further, or learning more about the central themes of its history — local and regional government power sharing in the Bay Area, effective organization of regional governing bodies, and local participation in city planning, to name a few — can find much more in OHC’s numerous projects and individual interviews. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria from the OHC home page.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Related Oral History Center Projects

Covering the years 1953 to 1966, the Oral History Center (then the Regional Oral History Office) began the Goodwin Knight-Edmund G.Brown, Sr., Oral History Series of the State Government History Project in 1969. It covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966 and contains 84 interviews with a diverse set of personalities involved in Californian public administration. Topics include but are not limited to the rise and decline of the Democratic party, the impact of the California Water Plan, environmental concerns, and the growth of federal programs. This series includes the multivolume “San Francisco Republicans,” which includes the oral history of George Christopher, “Mayor of San Francisco and Republican Party Candidate.”

The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Oral History Project, launched in May of 2012, is a collection of 15 interviews that cover the construction of the Bay Bridge, maintenance issues, and the symbolic significance of the bridge in the decades after its construction. The majority of interviewees in this project spent their careers working on or around the bridge as architects, painters, toll-takers, engineers and managers, to name a few.

The California Coastal Commission Project traces the development of the only California commission voted into existence by the will of the people, from the campaign for Proposition 20 that created the agency in 1972 to the various development battles it confronted in the decades that followed. These interviews document nearly a half century of coastal regulation in California, and in the process, shed new light on the many facets involved in environmental policy.

Listen to the “Saving Lighthouse Point,” podcast, a collaboration between the OHC and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University. “Saving Lighthouse Point” tracks the successful effort by citizens of Santa Cruz, with the support of the California Coastal Commission, to block the development of a bustling tourist and business hub on one of the last open parcels of land in the city.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

City and regional planning for the Metropolitan San Francisco Bay area, Kent, T. J., 1963. Bancroft Library/University Archives, Bancroft ; F868.S156K42

Open space for the San Francisco Bay area; organizing to guide metropolitan growth, Kent, T. J., 1970. University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Governmental Studies. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft ; F868.S156.57.K4

Regional plan, 1970–1990 – San Francisco Bay region, Association of Bay Area Governments, 1970. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft Pamphlet Double Folio ; pff F868.S156.8 A82

The BART experience: what have we learned? Webber, Melvin M.; University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Transportation Studies. 1976. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m r42 W372 b

Summer Listening

The Oral History Center Director’s Column, June 2022

By Paul Burnett

Interim Director, Oral History Center

For many of us, summer brings the promise of vacation, or at least time off with friends and family to rest, celebrate, or explore the great outdoors.

Whether spending time in parks fits into your summer plans or not, you owe it to yourself to check out the Oral History Center’s new project on the history of Save Mount Diablo, and especially the accompanying podcast. Shanna Farrell, Amanda Tewes, and student research apprentices Anjali George and Andrew Deakin did an amazing job of telling the story of fifty years of this important land conservation organization in the Bay Area and Northern California. The three episodes span key aspects of its history, which involved grassroots organizing; drawing on youthful energy and the expertise from older, larger environmental groups such as the Save the Redwoods League; management of invasive species; competition with developers for land; reintroduction of endangered species; the role of artists in the movement; and the potential fate of the area as the organization battles climate change.

For more interviews on the history of parks and environmental movements, check out the projects on the East Bay Regional Park District, natural resources, and the Sierra Club.

As you are listening to the podcast, we hope you’re lucky enough to get some time to visit some green space near you and appreciate the wonders all around us.

One of the things we’ve also been doing this summer is moving house to a brand new website. However, there are currently no automatic redirects from our old site, so please bookmark our new home page. It will take a while for this new site to come up in search engines, so that will be the best way to reach our great content for now. You can go directly to our blog here.

And as this summer and recent events turn our attention both to sports and women’s rights, one of our student editors William Cooke has written a piece on the 50th anniversary of Title IX, the landmark law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex at schools that receive federal funds, and its impact on athletics at UC Berkeley.

Stay tuned for our next newsletter in August!

Happy summer!

Paul