Author: Tor Haugan

Which American presidents have visited UC Berkeley? 🇺🇸

![After Theodore Roosevelt's visit to UC Berkeley, he toured Yosemite. Here he is seen at Glacier Point with naturalist John Muir. (Courtesy of The Bancroft Library [full credit below])](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ROOSEVELT-MUIR.jpg)

In honor of Presidents Day, here’s a list of the sitting presidents who have visited Cal. We’ve tried our best to be comprehensive, but for brevity, we’ve excluded visits by presidents before or after their time in office, as well as the president who had an official visit scheduled but canceled — we’re looking at you, William McKinley.

Much of this information appeared in a past Library exhibit called All Hail to the Chief, and the Library resources related to each president listed are by no means comprehensive.

1. Benjamin Harrison (1891)

During the spring of 1891, Benjamin Harrison came out for a visit, along with his wife and some of his cabinet members. After spending time in Southern California, his welcome in San Francisco “was a tremendous one of blazing lights, firing of cannon, tooting of whistles and pyrotechnics galore.”

On May 2, Harrison visited Berkeley, delivering a brief speech at the university, heralding the importance of institutions of higher learning. Later that day, he headed to Oakland, but the crowds were so unruly there that he couldn’t make it to the stand where he was supposed to speak. Instead, he delivered his speech while standing up in his carriage.

More: An account of Harrison’s travels, Through the South and West with the President, April 14-May 15, 1891, compiled by John S. Shriver, is available at The Bancroft Library.

2. Theodore Roosevelt (1903)

Theodore Roosevelt visited UC Berkeley in 1903, while he was president, as well as after his presidency, in 1911.

Roosevelt was friends with UC President Benjamin Ide Wheeler dating back to when Roosevelt was the governor of New York and Wheeler was teaching at Cornell University. When Roosevelt was planning a trip to California, Wheeler invited the president to speak at that year’s commencement ceremony. Roosevelt — a loyal pal — obliged.

The president was escorted to campus by mounted African American “Buffalo Soldiers” and gave the commencement address in the Greek Theatre, which, at the time, was not yet finished.

Afterward, Roosevelt, ever the outdoorsman, toured Yosemite, bonding with legendary conservationist John Muir.

More: The picture of Muir and Roosevelt that is shown above is part of Bancroft’s pictorial collection. Letters between Roosevelt and Muir are available on Calisphere.

3. William Howard Taft (1909)

William Howard Taft visited Berkeley in October of 1909, not long after taking office, an occasion marked by tragedy.

He was supposed to have been greeted by Beverly L. Hodghead, Berkeley’s first mayor, and mathematics professor Irving Stringham, who served as dean of faculties.

But that’s not what happened.

Stringham — who had fallen ill — died the morning Taft arrived. But despite that tragic turn, Taft’s visit otherwise went smoothly, with the president making a grand entrance — complete with a cavalry troop and university cadets — at the Greek Theatre, where he delivered an unplanned 10-minute address.

More: Bancroft holds an invitation from Taft’s reception during the visit. And many of the papers of then Oakland Mayor Frank M. Mott relate to Taft’s visit to Alameda County.

4. Woodrow Wilson (1919)

Woodrow Wilson — with the fitting nickname of The Professor — visited UC Berkeley as president in September of 1919, on a tour meant to garner support for America’s participation in the League of Nations, the international peacekeeping organization established after World War I.

At the time, Wilson was eyed as a potential successor to the recently retired UC President Benjamin Ide Wheeler.

Wilson, who apparently had been instructed by his physician to avoid speaking, made an unexpected speech at the Greek Theatre.

Not too long afterward, Wilson’s health began to decline. After a series of strokes, Wilson ended his tour early. Plagued by health problems, he spent the rest of his term secluded in the White House.

More: Photos from Wilson’s visit are held at Bancroft and are available on Calisphere.

5. Harry S. Truman (1948)

President Harry S. Truman delivered the commencement address here in 1948. Professor Garff Wilson, in charge of ceremonies and protocol, estimated 60,000 attended the event, but a local Republican-owned paper ran a photo of seats that were left empty on purpose, stating the stadium was “sparsely filled.”

More: BAMPFA Film Archive has an 11-minute film documenting the commencement.

6. John F. Kennedy (1962)

The last sitting president to visit Cal, John F. Kennedy spoke in 1962 on Charter Day, which marks the founding of the university. A crowd of nearly 100,000 descended upon Memorial Stadium, making it the largest audience Kennedy had addressed, and Kennedy was awarded an honorary law degree.

More: The Library holds the binder and manuscript of the speech used by Kennedy. The Library also has video recordings of the speech, which is also available to view digitally on Calisphere.

Who else?

In more recent times, Barack Obama’s oldest daughter, Malia, scouted UC Berkeley on her college tour — but her father was nowhere to be seen.

Malia eventually opted to attend Harvard, her parents’ alma mater.

But, hey — at least it wasn’t Stanford.

California Faces: The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection, Muir, John–POR:65. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

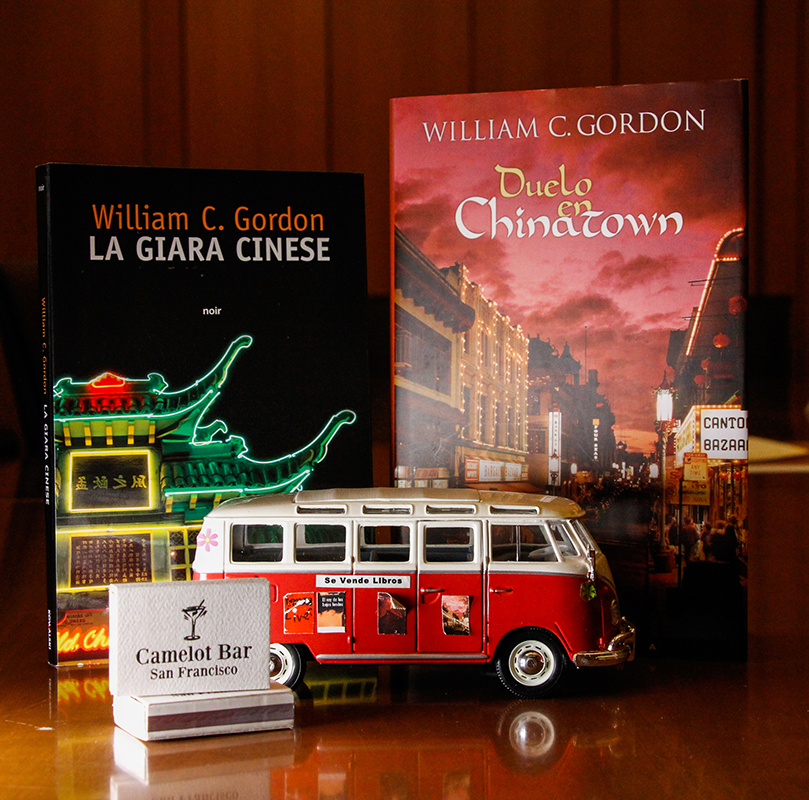

Stranger than fiction? UC Berkeley alum Willie Gordon’s life story comes quite close.

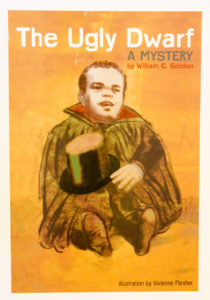

In his novels, Willie Gordon writes about people on the fringes of society: an oversexed dwarf, a dominatrix, an albino sage.

But it’s when discussing his real life that things start to get truly strange.

Gordon once hitchhiked across the globe, sleeping in cemeteries to save money. He had a 27-year marriage with international best-selling Chilean-American author Isabel Allende. His father was a preacher, having invented his own religion, called The Infinite Plan.

“The story of my life is more interesting than anything I could ever write,” says Gordon, 80, in a phone interview.

Gordon, who calls Marin County home, also is a supporter of the UC Berkeley Library. A recent donation will provide a “significant boost” to The Bancroft Library’s burgeoning California Detective Fiction Collection — which numbers about 3,000 (and counting) mystery novels set in the Golden State or written by California authors.

“Not only will we be able to add important titles to the collection, but this gift also provides funds for cataloging and processing, enabling us to make the materials available for research much sooner than would otherwise be possible,” says Randal Brandt, who curates the collection, in addition to serving as the head of cataloging at Bancroft.

Gordon also donated manuscripts, ephemera, and 22 volumes of his books in foreign languages.

Having his work immortalized in Bancroft’s collection is “like getting the Nobel Prize,” he says.

“When they make you part of the Library and there’s a chance to give something back, I don’t know, it was just perfect,” he says. “It was just unbelievable. I was so happy with that. Even now, I can’t tell you how wonderful it is.”

A safe haven

Gordon’s affinity for libraries began unexpectedly.

His father died when Gordon was only 6, and after his death, the family moved to a depressed area of East Los Angeles.

“We were broke,” Gordon recalls.

On his first day of school, Gordon walked out of the school’s gate to a startling sight: A gang of five boys were waiting to beat him up. They began to chase him. Gordon, seeking safety, ran into a church.

“I kept yelling for God to help me,” he says.

But Gordon didn’t stand a chance. The boys, he says, “beat the (expletive) out of me.”

Sure enough, the next day, the gang of boys were waiting for him again.

“I figured I could run fast and avoid these guys again,” Gordon says.

And he did run — but this time, he darted straight to a library he noticed on a side street on his way to school. This time, safe inside the library, Gordon avoided a second beating.

And then the learning started.

He asked the librarian to show him the kids section — and to teach him the alphabet — to which she obliged.

“I would go there every day after school,” he says. “And she taught me how to read.”

Man of mysteries

If there’s a typical path to becoming a mystery writer, Gordon didn’t take it.

“I knew (from) the time I was 6 years old I was going to be a writer,” Gordon says. “I knew I was going to be 60 years old. So it all worked out.”

As a second-grader, an enterprising young Gordon shined shoes to make a buck. He would take his shoeshine box, which he built, hop on a streetcar to downtown Los Angeles, and peddle his services on Main Street, “where all the winos were,” he says.

“On the streetcar you would find dime novels that people would leave — discarded mysteries,” he says. “So I would read those.”

And so began his love for the genre.

Gordon gravitated toward writers such as W. Somerset Maugham and Erle Stanley Gardner. As a mystery writer, Gordon describes his fondness for using plot twists in his own work as being inspired, in part, by Maugham (“I like to surprise the reader,” Gordon says). And Gardner, best known for his stories revolving around criminal defense lawyer Perry Mason, was a lawyer, a career Gordon would go on to pursue. “I loved him,” Gordon says of Gardner. “I thought he was fantastic.”

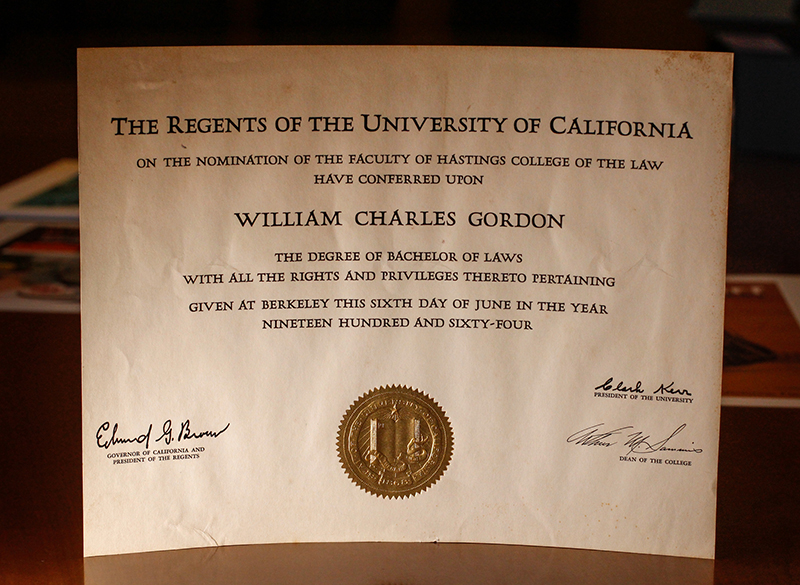

Gordon’s own law career began in 1965, after graduating from UC Hastings College of the Law, in San Francisco, a year earlier. By that time, Gordon had graduated from UC Berkeley with an English degree (“I loved it,” he says) — and had served a stint in the Army. From 1965 to 2002, Gordon represented people with workplace injuries — including many poor Latinos.

“When I was a lawyer, I basically took care of the little guy,” Gordon says. “Those were the people I knew.”

And, perhaps not coincidentally, the “little guy” — characters at the margins of society — eventually made their way into Gordon’s work, after he retired from his legal career and started a second act as a mystery writer — at age 60, as he predicted.

Two decades into his career as a writer, Gordon has released six books in a series of noir mysteries set in 1960s San Francisco that chronicles newspaper reporter Samuel Hamilton. Gordon made Hamilton’s profession a reporter — instead of a cop or an investigator, or even a lawyer — because, as he puts it, “I needed someone who needed to get help from everybody.”

“You have all kinds of people who have no names to the rest of the world,” he says, “but they’re the ones who help you get through life.”

The characters in Gordon’s book include an albino Chinese sage, inspired by a real person Gordon saw in San Francisco; a dominatrix, modeled after his father’s real-life assistant; and an oversexed dwarf, based on Gordon’s father, who he describes as “emotionally a dwarf.”

“Everyone has a place,” he says.

In addition to drawing from real life, Gordon also attributes much of his ideas to what he calls “creative realization.”

“I have to visualize it before I can write about it,” he says. “Because I write about what I see.”

This approach, he says, is something he shared with the celebrated writer Isabel Allende (who in 2014 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama). Allende’s 1991 novel, “The Infinite Plan,” largely draws from Gordon’s life. The book, Gordon says, is “emotionally accurate.”

“You visualize things as they’re needed in your work,” he explains. “I noticed that Isabel did that, too. I was totally shocked that we shared that. As a writer, that’s all you need.”

Gordon had already known how to tell a story, but, during his relationship with Allende, she helped him hone his craft. Each character has to have a meaning, she taught him, and “how you describe a character emotionally is as important than anything else.”

“And then you do what you’re good at,” he says.

‘All my dreams’

These days, Gordon is working on a collection of short stories. He’s about halfway done.

But at this stage in life, Gordon’s impact extends beyond that of his written work. As a philanthropist, he has given back to causes near to his heart.

In Southern California, he has contributed to the libraries at Whittier High School, where he served as student body president many years ago, and Los Nietos Middle School (Gordon is a Los Nietos alum), and he provided funding for a learning center in Santa Fe Springs. With his donations to Bancroft, he says, “I wanted to save the best for last.”

Gordon is bursting with stories. And after listening to him tell some of them, one thing becomes clear: He has lived a full — and successful — life.

Is there anything he has yet to accomplish?

“I’ve fulfilled all my dreams,” he says.

“I’ve completed everything I’ve wanted to complete,” he adds. “And I’m not finished.”

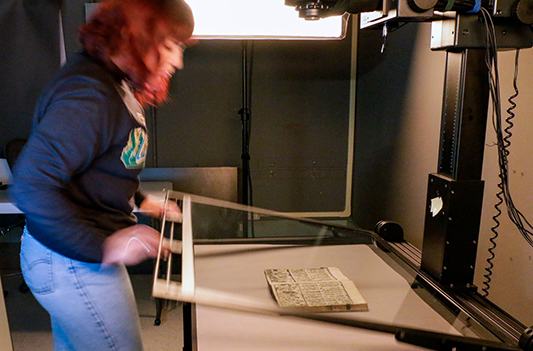

Watch: Rare book gets vibrant new life with help from Library

How can the UC Berkeley Library help breathe new life into old materials?

Just ask Jonathan Zwicker.

Over the course of the fall semester, Zwicker and students from his Seminar in Classical Japanese Texts worked on translating and historically annotating a rare book from the Library’s collections.

The goal? To make a factually enriched translation of the book available online, where it can be used by scholars across the world.

The original book, digitized in Moffitt Library, is a travelogue by Japanese author Kyokutei Bakin, chronicling the people he met and the strange things he saw on his travels from Edo — modern Tokyo — to Osaka and Kyoto in the early 1800s. (One interesting thing he encountered? A robotlike mechanical crab that holds a sake cup, made to deliver rice wine to guests. Bottoms up!)

In researching and annotating the text, Zwicker and his students tied the book to other Library materials, such as 19th-century maps, to bring the work to life and provide historical and geographic context.

This project marks the first time the book has ever been translated and historically annotated.

“I didn’t actually have a definite idea of what I wanted to come out of (the project) other than that it would be somehow available online in some way — to leverage these new technologies to make what we were doing both open to people but also to show the interconnections between the different materials,” said Zwicker, associate professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. “That’s, to me, the most interesting part of the book.”

Zwicker’s project is just one part of a broader collaborative effort guided by the Library that offers grants to help make educational resources openly available to students at UC Berkeley — and to scholars everywhere.

“Our program has a dual focus — first, on the creation of open textbooks to yield cost savings for students,” said Rachael Samberg, scholarly communication officer at the UC Berkeley Library, who is directing the effort, “and second, for other courses, it’s more about how incentivizing the creation of open books encourages pedagogically and scholarly innovative projects that benefit not just Berkeley students, but also researchers around the world.”

Zwicker said he hopes that going through the process of creating a new text will help provide a model for others who are pursuing similar projects. He’s already planning to pursue more projects like this one in the future.

And, he said, he couldn’t have done it without the support he received from the Library.

“It’s incredibly rewarding to feel that there’s this much enthusiasm for this kind of work and institutional support, and people are really — they’re not just providing help, but they’re also providing moral support,” he said. “And that’s invaluable.”

Happy holidays! Here’s a musical gift from the UC Berkeley Library.

The holiday season is a time for joy, gratitude, and, of course, music. This year, we asked a special guest — and Bach enthusiast — to play a composition from the Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library, home to some 200,000 volumes of books and printed music.

The Music Library is just one of 25 libraries that inspire, empower, and serve the scholars of this great university, with your support.

We hope you enjoy this musical treat!

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove, a Pulitzer Prize winner, fills Morrison Library with poetry

“It does the heart good to be among books and people who love them,” former U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove said to a packed Morrison Library audience.

As part of the Lunch Poems series, Dove read from a diverse selection of her work Thursday afternoon — recent poems and ones from further back in her extensive catalog, which includes Thomas and Beulah, winner of the 1987 Pulitzer Prize in poetry.

“It is so wonderful to see this room so full of people who love poetry,” Chancellor Carol Christ said during her opening remarks to a standing-room-only crowd of about 250 people. Christ, fittingly, began her academic career in the English Department, teaching poetry. “I have never been to an event here where there are people literally hanging from the balcony, so that says a lot about Rita Dove and says a lot about this community’s love for poetry.”

Dove was not only the first African American to be elected U.S. Poet Laureate — at 40 years old, she was the youngest, too. She now teaches at the University of Virginia.

The work Dove read Thursday included poems about family; an homage to the library near where she grew up, in Akron, Ohio; and the creatively alliterative Ode to My Right Knee (which opens, “Oh, obstreperous one, ornery outside of ordinary”).

Among those in attendance was Chelsea Muir, a public policy graduate student. She popped in for part of the reading after seeing a flyer.

“I liked the creativity and the playfulness,” she said, citing, in particular, a flowing prose poem Dove read. Muir said she was impressed by the reading and was inspired to read more of Dove’s work. She also enjoyed Morrison Library, which she was visiting for the first time.

Dove expressed a similar sentiment: “It just feels good in here,” she said.

ABOUT LUNCH POEMS

Lunch Poems is a noontime poetry reading on the first Thursday of the month. Admission to the Morrison Library event is free. Check out the spring semester schedule. Watch videos of past readings. Support for this series is provided by Dr. and Mrs. Tom Colby, the Library, The Morrison Library Fund, the Dean’s office of the College of Letters and Sciences, and the Townsend Center for the Humanities. These events are also partially supported by Poets & Writers Inc., through a grant it has received from The James Irvine Foundation.

‘Llama love’ makes its way to Memorial Glade at UC Berkeley, outside Doe Library

It might be the start of Dead Week, but Memorial Glade was more alive than usual Monday afternoon, thanks to four special guests.

Their names? Quinoa, Ollantaytambo, Amigo, and Wykee.

For about four years, llamas have been descending on campus, offering students a much-needed respite from their studies — and soft coats to pet.

Monday’s event, called Return of the Llamas — sponsored by the ASUC’s Office of the Academic Affairs Vice President — drew large crowds of students, who came to pet the llamas and take pictures with them, with some onlookers climbing on each other’s shoulders to get a better vantage point.

“They are an institution,” said George Caldwell, or Geo, who has brought his fluffy friends from Sonora, more than two hours away in Tuolumne County, to the UC Berkeley campus for various events and activities, including events raising awareness about wellness and suicide prevention.

Caldwell teaches classes in Oakland about the ungulates. Afterward, he said, he comes to campus with the creatures “to share the llama love.”

“My whole goal is to have llamas here 365 (days of the year),” he said. “It would be a great thing for people who have stress to go see the llamas.”

Ana Mancia, department head of the Office of the AAVP for the ASUC, has been instrumental in bringing the llamas to campus for the past year and a half — which equates to three rounds of llamas.

“I really hope (students) get the chance to … ease the pressure before finals,” said Mancia, a third-year business major. The llamas, she said, could help students “put things in perspective.”

So how are students reacting to the creatures?

“They’re crazy and fun,” said Wei Zhou, an economics major who was there with her friend Nancy Zhu, an applied math major.

“It’s a good way to de-stress,” Zhu added.

So long, Twitter and Facebook: UC Berkeley students take a timeout from social media

Forgoing Facebook? Taking a timeout from Twitter? The prospect of a social media sabbatical may seem unthinkable to some millennials.

But on the fourth floor of Moffitt Library on Monday morning, a throng of students were lined up to surrender their smartphones — voluntarily — for a social media blackout.

A collaboration between the REST Zones Project and the Office of the Academic Affairs Vice President, the Blackout Challenge encourages students to fork over their phones in exchange for prizes, depending on how long they participate. One hour will get you a sleep mask. Two hours, and you’ll get a stuffed bear. Three hours will earn you a pillow. And if you last four hours, you’ll get a blanket. While supplies last, of course.

“We hope to enhance the productivity of students during Dead Week,” said Genevieve Slosberg, an intern for the Office of the AAVP, who was working the event Monday morning. “We also hope to be a part of creating a culture where social media is not as prevalent.”

How do UC Berkeley students feel about giving up social media?

“It’s probably going to make me study more,” said Cameron Chee, a sophomore majoring in chemistry.

“I cannot last longer than three hours,” said Anna Mazur, who is studying Environmental Economics and Policy, citing a review session she was attending later.

Some students were in it for the long haul. Joseph Sahyoun, a grad student studying mechanical engineering, said he was aiming to participate for the full four hours — at least.

“I support it,” he said of the effort to unplug from social media. Plus, he said, “I love sleep gear.”

Turnout Monday morning was “extremely high,” Slosberg said. About 25 minutes in, 30 people had surrendered their phones — a rate of more than one phone per minute.

How did so many students find out about the event?

“Facebook,” said Chee, echoing other students’ replies. “Which is kind of ironic.”

The Blackout Challenge started at 10 a.m. at Moffitt Library and lasts until 10 p.m.

Net neutrality, Trump’s tweets, and the rise of wireless culture: UC Berkeley professor’s new book illuminates modern issues by exploring the past

“Sound is really important in the history of literature, technology, and culture,” Tom McEnaney said. “It’s not merely a metaphor.”

And McEnaney knows a thing or two about sound.

The UC Berkeley professor, who earned his Ph.D. from Berkeley in 2011 and returned this year to teach in the Comparative Literature and Spanish and Portuguese departments after six years at Cornell University, has researched and written extensively on the subject.

He has a forthcoming piece about how This American Life has set a new standard for voices on the radio. (The vocal fry and uptalk you hear on NPR? That wasn’t always so common.)

And he has taught classes on punk rock, co-curated an exhibit about punk history, and has made noise in many punk bands over the past 20 years.

So it’s fitting that sound factors heavily into McEnaney’s new book, Acoustic Properties: Radio, Narrative, and the New Neighborhood of the Americas.

On Dec. 4, Morrison Library is hosting an event — a conversation with McEnaney, Emory University’s José Quiroga, and UC Riverside’s Freya Schiwy (“two really wonderful scholars whose work I admire,” he said) — that celebrates the book.

McEnaney’s book explores the “coevolution” of the radio and the novel amid influential movements in populist politics in three countries in the mid-20th century: the New Deal in America; Peronism in Argentina, and the Cuban Revolution. The book illustrates how governments, activists, and artists have struggled for control to represent the voice of the people within a changing media landscape.

“This is really the intersection of a turn to populism on the left” — liberalism in the United States, socialism in Argentina, and communism in Cuba — “with wireless (technologies) that open the possibility, not always actualized, of giving power to the people,” McEnaney said.

His book talk will shine a light on the “unknown and unrecognized history of the hand-in-hand development of two strong media of public discourse” — radio and the novel — during pivotal moments for these three countries, said Liladhar Pendse, a librarian who is helping organize the event, along with Natalia Brizuela, a professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

McEnaney wears many hats. In addition to his research and teaching, he founded the Latin American Journals Project, established through a grant he received while at Cornell, which, in part, aims to provide scholars and the general public with free and open access to Latin American journals, many of which are otherwise be difficult to find.

McEnaney’s work on Acoustic Properties was bookended by two major political groundswells in the United States. He started the book, which evolved from his dissertation, in 2008, the year that Barack Obama was elected to his first term as president. The book came out in 2017, the year Donald Trump took office.

McEnaney’s book is timely, given today’s climate, and provides context for the current discussion about net neutrality. “The debates of how to regulate radio are the same debates we’re having with the internet,” he said.

“It’s about many things,” McEnaney said of his book. “It’s attempting to understand our present moment through histories of technology, literature, and politics.”

The book covers Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “fireside chats,” which saw the president embracing the relatively new platform of radio to convey his message. It’s not unlike the way Trump has embraced Twitter — setting aside the differences in tone.

“(It’s) a different type of politics but very much connected to the way the president of the United States uses wireless technology to create the illusion he’s speaking directly to the people,” he said.

While Trump is known for his shoot-from-the-hip candor, Roosevelt’s style was intimate and controlled. (Roosevelt and his advisers were so concerned with the president’s tone, as the book notes, that they had him use a dental bridge to close a gap in his teeth to prevent the whistle in his voice during his radio addresses.)

With his knowledge of populist movements of the past, did McEnaney foresee the upswell that ultimately catapulted Trump into the White House?

“Did I predict it? No,” he said. “It’s a new, troubling twist in the story.”

The book talk, called “Sound, Media, and Literature in the Americas,” will be held in Morrison Library on Dec. 4, and it starts at 5 p.m.

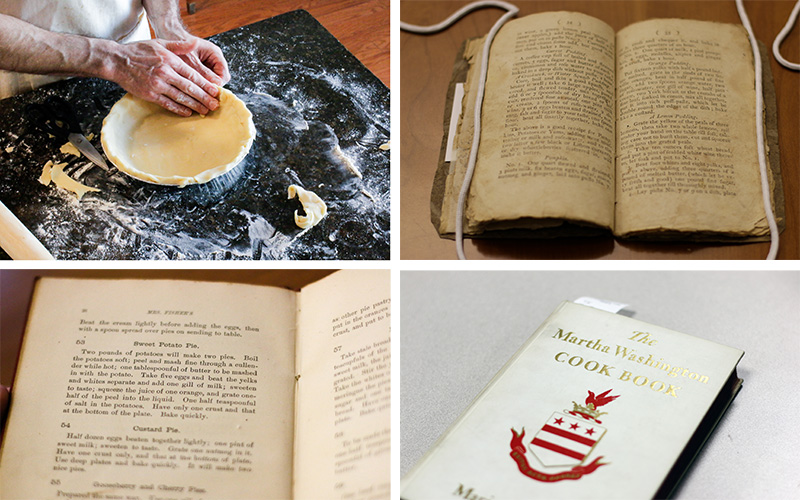

For Thanksgiving, we tried 3 historical pie recipes. How do they hold up today?

Thanksgiving is almost upon us. And you know what that means.

That’s right: It’s pie season. After all, mustering up the mental fortitude to feast alongside that obnoxious out-of-town uncle you see once a year should be rewarded with a decadent dessert, right?

We think so.

So we turned the clock back — way back — by baking and taste-testing three historical pie recipes from our collections to see if they would satisfy the modern palate.

The three recipes we chose come from books published in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries — well before Pinterest and the advent of the celebrity chef. That’s right — you won’t find Rachael Ray’s or, heavens forbid, Paula Deen’s names on any of these recipes.

Instead you’ll find three distinct, delectable desserts, each one holding its own historical significance — and each giving you a taste of the Library’s offerings and even, perhaps, baking inspiration for Thanksgiving.

A holiday classic

We started with the grandaddy of them all: pompkin pie. That’s no typo — “pompkin,” it turns out, is an old-timey way of saying “pumpkin.” And no Thanksgiving would be complete without this holiday favorite.

The recipe comes from The Bancroft Library’s second-edition copy of American Cookery — one of about 900 cookbooks in Bancroft’s collection. It’s a modest-looking volume, published in 1796, that came to Bancroft within the past decade or so.

“It came in, and no one realized the significance of it,” said David Faulds, curator of rare books and literary manuscripts at Bancroft.

The book packs historical significance: It is the first known cookbook written by an American. “It was the standard American cookbook,” he notes.

It’s also incredibly rare.

Just how rare is it? Well, Bancroft’s copy is believed to be one of five or six copies in the world. After living a quiet life at the Northern Regional Library Facility in Richmond, it now is kept in Bancroft’s vault and was recently featured in New Favorites, an exhibit highlighting recent additions to Bancroft’s major collections.

But let’s cut to the chase: How does this pompkin pie actually taste?

To find that out, we put the pie in front of a tasting panel including Faulds and four students (full disclosure: All are avowed pie fans) whose majors — and opinions — ran the gamut. All in the name of research, of course.

“It doesn’t taste quite modern,” one taster said, noting the lack of cloying sweetness.

It does, however, contain many of the hallmark pumpkin pie spices — nutmeg and ginger, among them — which have become ubiquitous in recent years. (Pumpkin pie spice potato chips, anyone?)

Perhaps the most notable difference is the lattice crust on top, which is absent in commonly used pumpkin pie recipes today.

But would the pie hold its own alongside more modern fare?

That’s a resounding yes, according to our panel.

Another classic — with a twist

Next up is another holiday staple: Sweet Potato Pie.

Like the pompkin pie, this one tastes familiar. But it also has an unexpected, zippy twist.

“I like the tang it has to it,” a taster said. “I’ve never had that in a pie.”

One panelist said it tasted like pumpkin and orange, while another swore it was carrot and lemon. (The “citrus-y” taste they noticed actually comes from orange juice and zest.)

The recipe traces back to What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, from 1881 — copies of which are held at both Bancroft and the Bioscience & Natural Resources Library.

Written by a former slave and plantation cook who moved from Mobile, Alabama, to San Francisco, it is thought to be one of the first cookbooks written by an African American. (It was believed to be the first cookbook written by an African American until the rediscovery of Malinda Russell’s Domestic Cook Book, published in 1866.)

And it was award-winning, too: At the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Fair in 1880, it won awards for best pickles and sauces as well as best assortment of jellies and preserves. (The author ran a pickle business.)

According to a later edition of the book, the namesake Mrs. Fisher — Abby Fisher — didn’t know how to read or write. Instead, she dictated the recipes to a group of prominent San Francisco and Oakland residents.

Of all the recipes, the terminology in this one had us scratching our heads the most. We felt that we could safely assume that a “cullender” was a colander. And “yelks,” it seemed, clearly referred to “yolks.”

But what is a “gill” of milk?

It turns out, it’s an antiquated measurement equaling half a cup — and does not, as one taster guessed, involve filling a fish with milk.

Presidential treatment

Then there’s the Quince Pie.

This one comes from the family cookbook of our very first first lady, Martha Washington. That’s right — move over, Melania Trump.

A quince, if you’re not familiar, is a yellow fruit that looks like a pear but tastes like a “woody apple,” as one taster put it.

A note: We’re using the word “pie” loosely here, because, although it looked beautiful in the pie tin, our attempts to cut it turned it into a crumble. That combined with the reddish tint of the cooked quinces seemed to confuse our tasters — and the resulting presentation looked almost gorey.

“It looks like body horror,” as one taster subtly (yet accurately) put it.

Other responses included that it looked like rhubarb, grapefruit, papaya, or even sashimi.

Though the texture was firm, the tasters agreed the pie was better than it looked, with at least one panelist declaring it the best of the bunch.

The recipe comes from 1940’s The Martha Washington Cook Book, adapted from Washington’s family cookbook. It’s one of the more than 5,000 cookbooks housed at the Bioscience & Natural Resources Library.

Notably, it’s the only recipe we tried that includes exact measurements. According to Faulds, the old practice of omitting measurements was actually quite common.

“That was the standard,” he said. “They assumed we knew what we were doing. They weren’t thinking about 200 or 300 years later.”

The recipe is straightforward enough, with the filling calling for just three simple ingredients: sugar, water, and quinces.

The pie, once ready, can be topped with whipped cream, but, as the recipe sternly notes, “Martha Washington did not do this.”

But this is not the time for holding back. Go ahead and pile on some whipped topping, and enjoy. After all, Thanksgiving happens only once a year.

Martha Washington would understand.

Note: We used recipe No. 1. This recipe refers to other recipes that can be found in the digitized version of “American Cookery,” found here.

No. 1. One quart stewed and strained, 3 pints cream, 9 beaten eggs, sugar, mace, nutmeg and ginger, laid into paste No. 7 or 3, and with a dough spur, cross and chequer it, and baked in dishes three quarters of an hour.

No. 2. One quart of milk, 1 pint pompkin, 4 eggs, molasses, allspice and ginger in a crust, bake 1 hour.

From: American Cookery, 1796

Two pounds of potatoes will make two pies. Boil the potatoes soft; peel and mash fine through a cullender while hot; one tablespoon of butter to be mashed in with the potato. Take five eggs and beat the yelks and whites separate and add one gill of milk; sweeten to taste; squeeze the juice of one orange, and grate one-half of the peel into the liquid. One half teaspoonful of salt in the potatoes. Have only one crust and that at the bottom of the plate. Bake quickly.

From: What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking, 1881

8 quinces

1 ¼ cup sugar

1 ½ cups water

Pastry

Wash the quinces. Cut in quarters, remove cores, and peel. Put in a pan together with one cup sugar and water, and let stew very slowly until tender. Turn fruit often. Line a pie plate with pastry and arrange the quinces in it in a neat design. Pour on the syrup and sprinkle with remaining one-fourth cup sugar. Lay criss-cross pieces of pastry on top and bake until a golden brown. The top pastry may be omitted and the pie covered with whipped cream before serving. Martha Washington did not do this.

From: The Martha Washington Cook Book, 1940

Life, gene editing, and rock ’n’ roll: 5 things we learned from Jennifer Doudna’s talk

When Jennifer Doudna was in high school, a guidance counselor called her into his office to talk to her about her career.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” Doudna recalls him asking.

“I want to be a scientist,” Doudna said.

“Girls don’t do science,” she remembers him saying.

She has been proving him wrong ever since.

For one, the UC Berkeley professor co-invented CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, hailed as the biggest biological breakthrough since the discovery of DNA’s molecular structure in the 1950s. The technology comes with the possibility of curing devastating diseases and improving lives but also raises ethical questions.

“If you have a tool that allowed precision changes to DNA to be made,” she said, “that provides a way that, in principle, one could alter human evolution by making changes that could become inherited by future generations.”

In the years that followed, Doudna has become instrumental in raising awareness and broadening understanding — within the scientific community and beyond — about the technology. It’s a duty Doudna doesn’t take lightly. “It’s something I feel deeply passionate about,” she said.

Doudna sat down in front of an audience Tuesday in the Bioscience & Natural Resources Library for a chat about her book (“A Crack in Creation” is out this year), her life, and her scientific breakthrough.

Here are five things we learned.

1. Her upbringing in Hawaii influenced her career path.

Growing up, Doudna lived in Hilo, a “small, rural town,” on the big island of Hawaii. It was living in Hawaii, surrounded by diverse wildlife (“blind cave spiders and all kinds of interesting plants,” she said) that sparked her lifelong love of science.

“When I think back on how I got interested in science and biology and chemistry,” she said, “it really, I think, stems from growing up in that island environment and wondering about how organisms can evolve to live in a setting like that.”

And in 10th grade, Doudna’s interest in science deepend, thanks to a chemistry teacher, Miss Wong, who “taught us kids that science was about solving puzzles — it was about asking questions and figuring out how to answer them.”

“I absolutely loved it,” she said. “It was fun, and I started imagining that it would be really great to grow up and have someone pay me to do what I thought was just kind of fun — playing around in a lab.”

2. Even bioscientists get the blues.

In her 40s — and well into her second decade of running her lab — she started to question whether her work was going to have an impact.

“I really almost had sort of a midlife crisis,” she said.

She took a leave of absence at Berkeley for an opportunity at a company — which, in retrospect, was the wrong move.

Although it was a great company, she began to realize, “It was just the wrong fit for me,” she said. “I felt it in my gut. This is not where I’m meant to be.”

“I realized that I just loved working with students. I loved being at a public university,” she said. “I really believed in that mission of having education available to anyone who can come and wants to learn and wants to work at this wonderful place that we have here.”

She asked her former colleagues at UC Berkeley if she could return.

“They took me back,” she said.

3. She didn’t like the name of her book at first.

Neither Doudna nor co-author Samuel Sternberg liked the title “A Crack in Creation,” which their editor suggested.

“It sounded very ominous, somehow,” she said.

Neither could think of a better title, and they were eventually won over.

“It does sort of convey this idea that … we’re sort of at a fork in the road, in a way, and it really does feel kind of profound at times to me,” she said. “We’re at a point where now we as a species have a tool that will allow us to control … who we are.”

4. She has a complicated relationship with the spotlight.

“People have called me the public face of CRISPR, and I’m sort of shocked by it,” she said.

But with glare of the spotlight comes the opportunity to raise awareness and educate the public.

“I feel sort of a sense of honor that I’ve been sort of thrust into this position of being a spokesperson for science, and it’s something that I feel deeply passionate about,” she said.

5. She had a brush with rock royalty.

With her profile having reached new heights come opportunities that she had never previously imagined.

“I was at a thing in London not long ago, and I turned around, and behind me was (rock guitarist) Jimmy Page,” she said. “We just struck up a conversation. We started talking about science, and about guitars, and Led Zeppelin.

“And I said to him, ‘I’m such a fangirl. I mean, I listened to your music growing up. Would you mind if I took a picture with you?’

“And (now) I have a picture with Jimmy Page.”