Author: sfarrell

Stars and Scars: A Historian’s Lessons from 9/11

by Christine Shook

Christine Shook is an independent historian with over a decade of experience in oral and public history. She earned her master’s in history from California State University, Fullerton in 2010. Her previous positions include Museum Assistant at Mission San Juan Capistrano, Exhibits and Collections Associate at the Tahoe Maritime Museum, and Historian and Assistant Vice President at Wells Fargo’s Family & Business History Center.

September 11, 2001 was an incredibly surreal day. Never a fan of mornings, I awoke late on the Pacific Coast, turned on the TV, and found some sort of devastation unfurling in the east. I didn’t know what had happened. The newscasters had temporarily moved on from the footage showing the planes hitting the World Trade Center and were instead discussing the rescue efforts and fears that the buildings surrounding the towers might collapse. Terrified and utterly confused, I turned to the Internet for answers and first saw the footage of the second plane hitting the towers, and learned about the four planes that had crashed. I spent the next hour bouncing back and forth between the computer and the tv in an attempt to discover what I missed while staying on top of the latest events. It felt like one of those days when the rest of the world should have paused while this thing worked itself out, but that wasn’t the case. I had to go to work. I tamped down the overwhelming feeling of uncertainty I was experiencing, put on my work uniform, and prepared to face the public.

As a recent high school graduate, I worked the closing shift as an attendant at a swanky hotel spa in Dana Point, California. The spa was relatively empty that day. The only exception was a couple from New York who found themselves stranded in Southern California. Unable to fly home or contact any of their friends and family, they came to the spa hoping to find a much needed distraction from the things they could not control. They didn’t stay long.

Later that night, the rest of the spa staff and I spent the hours until closing in one of those drab back rooms that only hotel staff sees, adjusting the antenna on a radio so that we could hear the latest news. As I sat listening to the radio waiting for updates about these attacks on 9/11, my mind transported me to sixty years in the past to the attack on Pearl Harbor. I began to wonder if Americans in 1941 also experienced this atmosphere of angst, remorse, anger, and uncertainty. The events of December 7, 1941 led to years of war and sacrifice. Was that where we were heading?

I was not the only one pillaging the past in search of answers about an uncertain present. Politicians, pundits, pastors — everyone seemed to be making the same comparison to Pearl Harbor, and deriving strength and certainty from the virtue with which America responded to that particular wrong. A common message seemed to be: History has taught us that America is good, so our response will follow suit. Of course, I knew from the stories of family and friends that things were more complicated than that. My grandfather earned medals for his participation in WWII but no one in my family has them today. The physical and psychological wounds with which he returned inspired him to throw those medals into the Atlantic Ocean upon receipt. As a grad student in history, I read Stud Terkel’s “The Good War” and discovered more stories like my grandfather’s that casted doubt on the flawlessness of the conflict and the glorified way in which Americans remember it. The United States’s response to 9/11, the realities of war, and the uncertainty of government actions have similarly affected people in a variety of ways over the past twenty years. While the exact failings of the response to that day vary according to political parties, few think that the United States has handled things with the storied righteousness with which it started.

My own observations and lessons about 9/11 over the past two decades have been heavily influenced by my work as a historian. For the past six-and-a-half years I helped ultra-high-net-worth families examine their historic roots in search of values and lessons that they could apply to today — using the past to guide future choices and investments. When I first began this work, the message we offered clients was always one of hope: your family not only survived X, it eventually thrived financially. There’s value to that narrative of resilience, of course, but also a danger in overconfidence. In the past few years, I’ve noticed a promising trend where family members — especially those from younger generations — want to know more and more about the hard and uncomfortable truths from their past. They appear to recognize their ancestors as flawed people with cautionary tales that accompany the celebratory.

I can only hope that this willingness to look at cherished personal histories with a critical eye will expand to include the national narrative. Perhaps the next time America faces another crisis like 9/11, the stories of people like my grandfather, who rejected a jingoistic narrative, won’t be overlooked in order to provide quick answers to the question: what now?

9/11: An Oral Historian’s Personal Recollection

by Shanna Farrell

My memories of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 are vivid. I was sitting in my second period senior English class when my teacher, who was known for his sarcasm, delivered the news.

“Hi, everyone,” he said. “I just heard that a plane hit the World Trade Center.” The class began to laugh awkwardly.

“No,” he said. “I’m serious. I don’t have any more information than that.”

A hush fell over us, but we proceeded with class as normal. I’m sure I was distracted but we were discussing books and I love discussing books. Besides, it wasn’t yet real.

When the bell rang, I walked down the hall to my current events class, where our teacher routinely had a TV playing in the back of the room so he could watch the news while he taught. That’s where I first saw the images of the plane crash. Of the burning buildings. Of people falling through the sky. Of endless smoke. Of the clear blue sky. That’s when I realized I needed to call my mother, immediately. The tragedy was now real to me.

Despite the fact that my family’s residence at the time was in upstate New York, in a small mill town built on the banks of the Hudson River that hugged the Vermont border, my mother worked in New York City. She was in educational sales and her territory covered all five boroughs. She often had appointments at Stuyvesant High School, a building that is just blocks away from the World Trade Center. I knew this because even though my birth certificate indicates something different, I was partially raised in the city. My mom would often point out Stuyvesant High School when we would drive down the West Side Highway or walk around TriBeca or buy tickets for Broadway shows in the atrium of the World Trade Center. That morning, she was on her way there.

As soon as I reached the main office of my school, I pleaded with the administrative staff to let me use the phone to call my mother.

“My mom is there. My mom is there,” I repeated. I remember the horror wash over their faces, how one of them picked up the phone and instantly dialed “9” to get me an outside line. Since my mother spent so much time in her car, she had a hard-wired cell phone, cord and all. I punched in her number, but all I got was a busy signal. I did this over and over with the same results. I called my dad and the first thing he said to me was, “I can’t reach her either.” He promised to call me as soon as he heard from my mother. I hung up the phone and turned to see a few others in line behind me waiting their turn to call family or friends who also lived in the city. I didn’t know what else to do but return to class and watch the news on loop.

I’d felt fear watching major events unfold in the past, like six years earlier when a terrorist blew up a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. That had scared me. But this fear, the type I felt while waiting to find out if my mother was alive or dead, was something entirely different. It was panicked and unrelenting. Time seemed to stand still. I could have moved from room to room or stayed in the same seat. (I do, however, remember relocating to the cafeteria at some point where TVs had been wheeled in so we could watch the media coverage.) And then I heard my name over the PA system. I had a phone call and needed to report to the office.

“She’s okay,” my dad said. “She called me from a payphone. She was in Brooklyn.”

In the days that followed I would learn that my mother was headed to Manhattan from Brooklyn that morning, but got stuck on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway while she was en route. Traffic moved slowly, if at all, and she ended up snaking her way to the part of the expressway that is just under the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, a place known for its iconic view of the lower Manhattan skyline. From there, she watched with hundreds of others as the towers burned and debris floated across the harbor as the wind blew southeast. She was eventually able to make it to Queens, where she pulled over and found a payphone. I would later watch her struggle with what she had seen that day, hear her plead with me not to get on a plane in the coming weeks for a college visit, listen to her talk to colleagues and discover she knew people on the plane that crashed into the Pentagon.

The trauma of the event was lasting for her, for me, and for us as a family. We visited Ground Zero many times and I have memories of the smoldering ashes fading into piles of debris and later becoming a gaping hole in the ground. I remember the photos of the missing people stapled to the fence surrounding the site. I remember the tone of the city and the feeling of community. I remember being so happy that my mother was alive, and so sad that others hadn’t been as lucky. I remember how filled with grief each anniversary of the attacks were each year.

In September 2011, I was starting a master’s program in oral history at Columbia University. The Columbia Center for Oral History Research had started a massive interviewing project ten years earlier, the same day the towers fell. Interviewers–staff, student, and volunteers alike– recorded hundreds of life histories with a wide range of people who were affected by the attacks. They interviewed anyone who wanted to participate and returned to many months later to interview them again. I still consider this to be an innovative model for an oral history project, especially in a field that is constantly asking itself “how soon is too soon?” (For more on this, check out Amanda Tewes’s piece on interviewing around collective trauma.)

This project served as much of the foundation of the Columbia program and the interviews became the basis for a book, After the Fall: New Yorkers Remember September 11, 2001 and the Years that Followed, which was published as I began the Master’s program. As graduate students, we read through transcripts, listened to interviews, engaged with theory related to memory and trauma-informed narratives, learned methodology for approaching sensitive interviews, and expanded our studies into other topics, like genocide and mass-incarceration. We even watched a professor interview a paramedic who had been at Ground Zero that day, live in class, offering us the opportunity to practice our question-asking skills.

It was intense. But it made me into an interviewer who isn’t afraid to shy away from difficult topics. My training also gave me space to process my own grief around the 9/11 attacks. I found myself asking my parents more about that day and how they felt in the years that followed. It gave me a concrete example around which to center my work as an oral historian and how I should approach trauma in my own interviews. How would I want to be asked about these things? How would I feel if I cried in an interview? How would my tone, pace, and velocity of speech change when a difficult subject came up? What were my boundaries and how would I express them to an interviewer? Which of my memories were solid and which were porous?

In the conversations that I had with my parents after the tenth anniversary of the tragedy, I realized that many of my memories, no matter how vividly I remember that day, were not quite accurate. My mother explained that she hasn’t actually been heading to Stuyvesant High School. Instead, she was trying to get to a school on W 33rd Street through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, which enters Manhattan just south of the World Trade Center. This had been part of my narrative for years. My memory wasn’t perfect.

Now, twenty years later, I’m still using these experiences as the basis for how I approach trauma-centered narratives, and, for that matter, any interview where a sensitive subject comes up. It’s remarkable how much I use the same techniques that I learned in grad school, honing them over the past ten years. My pace, my tone, my body language, my ability to pause and give someone space, my interest in putting my feelings aside to privilege a narrator’s story all matters. As oral historians, we often take the life history approach, which can dredge up painful memories from the past, no matter how much we prepare in the pre-interview and planning process. I have to be ready to handle a narrator’s emotions about a troubled relationship with a parent, a divorce that proved formative to a career, a bad review in a newspaper, and yes, a terror attack.

It’s also made me mindful of people’s memories, especially around trauma. Though the historical facts of how I remember 9/11 remain static for me, the details of my mother’s experience were fuzzy. But it’s relevant to how we memorialize events, how we talk about them with our own communities, and what gets documented in the historical record. It’s also made me consider what gets left out of the left out of the story, perhaps because it happened too long ago, was repressed, or doesn’t feel as significant. For example, in talking to my mother about this very article that you’re reading, she told me that I was interviewed by the local newspaper shortly after September 11, 2001 about my experiences that day. I had my picture taken. I said that 9/11 had “changed my life.” Yet, I have no memory of being interviewed until or having my picture taken. And I have no idea why. I only vaguely remember hearing my parents talk about the article. In many of the oral history interviews that I’ve conducted over the last ten years, narrators often say to me, “I can’t remember the last time I thought about this.” That’s exactly how I felt when my mom told me about that newspaper article.

9/11 shaped me in countless ways. That cloudless Tuesday and its aftermath continue to be present in my life, following me from high school to graduate school to my work at the OHC. It’s informed the way I think about life pre-9/11 and over the past twenty years. I’m not sure my memories will ever be less vivid or more pliable, but the impact, personally and professionally, will persist.

Request for Proposals: New Oral History Symposium

Assessing the Role of Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Practice Symposium

Call for Proposals, EXTENDED DEADLINE of November 1, 2021.

Convened by the Ad Hoc Group for Transformative Oral History Practice in collaboration with the Oral History Association and the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley

It has been just over one year since a White police officer murdered George Floyd, sparking the largest call for racial justice in this country in a generation. Support for Black Lives Matter reached an all-time high in June 2020, with nearly 70 percent of U.S. adults holding a favorable opinion of the movement, and support spilling over to all corners of the globe. White Americans also helped take down Confederate monuments and bought books on antiracism in record numbers while corporations pledged millions of dollars to social justice organizations and causes. One year later, however, commemorations of Floyd’s life and legacy asked: “What’s changed since?”

We acknowledge that “Assessing the Role of Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Practice” is taking place amid revitalized demands for understanding – and changing – the systemic racism that enabled a White police officer to murder a Black citizen in daylight without seeming fear of repercussions. But it is also taking place at a time of fierce backlash to any understanding of the oppressive forces that enabled Floyd’s murder. At the time of this writing, some state legislatures have passed laws banning the teaching of critical race theory, even as a majority of states seek to suppress the Black vote and overturn our elections. Recent events such as these are causing many to evaluate the role of structural racism and White supremacy in the arts and humanities, including the practice of oral history.

Building on an enthusiastically received panel that asked “Is Oral History White?” at the 2020 Oral History Association annual meeting, participants in that session (calling ourselves the Ad Hoc Group for Transformative Oral History Practice), in collaboration with the Oral History Association and the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, are convening a symposium that will define, identify, analyze, assess, and imagine alternatives to conventional practices, prevailing ideologies, and institutional structures of oral history in the United States and Canada, as they pertain to historic and current forms of systemic racial discrimination. In essence, the symposium is moving beyond the question the 2020 panel asked – “Is Oral History White?” – to interrogate broader structures and dynamics of race and racialized thinking in oral history.

We are inviting proposals from oral historians and others involved in fieldwork-related interviewing practices, as well as critical race and Whiteness theorists, to submit proposals for symposium papers that pose major questions and offer precise assessments of racial constructs as a factor in all phases of oral history work: project design, research processes, financial and budgetary matters, fieldwork and community relations, interviewing, archival practices, and public presentation and interpretation of narrative materials.

The “Assessing the Role of Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Practice” symposium will take place via Zoom Webinar over a three-day period in June 2022. We expect to convene approximately thirty-five presenters, spread over six to eight sessions of two hours each. With the assistance of a moderator and/or one or more discussants, session presenters will summarize and discuss pre-circulated papers posted on a conference website, which will have also been made available to registered attendees in advance of the symposium. Symposium sessions will allow time for audience questions and comments, vetted and synthesized via the Zoom Webinar “Q&A” function by the session moderator. This format will allow for especially robust and probing discussion during sessions.

This symposium should present a significant opportunity for audience members to reflect personally upon the charged subject of race in oral history in a pedagogically constructive way. Discussions of racialized experience and representations in our field will raise not only important insights but also strong emotions. We expect our audience to have a vast range of racial identities and relationships – including but not limited to Whiteness and Blackness – and varying degrees of experience reflecting upon that. We therefore plan to set shared expectations for constructive conversation rooted in mindful awareness, good faith engagement, and emotional maturity at the very beginning of the symposium and to create opportunities for small-group discussion and individually tailored self-reflection over the duration of the symposium. We hope that the symposium’s virtual nature, with participants in the relative privacy and comfort of their own homes, will contribute to this aspect of the symposium experience. Above all, we plan to keep discussion focused on practical applications of whatever theoretical and conceptual insights into race in oral history our symposium may furnish.

Intended outcomes include publication of revised versions of selected conference papers in an edited volume and a white paper assessing OHA’s racialized history, practices, and programs, to be developed by symposium organizers. Organizers, in cooperation with OHA’s Equity Task Force and Diversity Committee, will also create and promulgate guidelines for racial equity in oral history.

Pending receipt of grant monies, we hope to provide honoraria for symposium presenters.

Proposal Information

Each proposal should include a title, an abstract of no more than 500 words, and a short biographical statement of no more than 300 words. Include your name, institutional affiliation if relevant, mailing address, email address, and phone number. The abstract must outline the research that you either have conducted or intend to conduct in support of your proposed presentation, the sources that you have consulted or will consult, and the collections in which you have conducted or will conduct research. While we anticipate that most proposals will be for a single paper, we welcome proposals for full sessions, also – to include 3-5 papers, moderator and discussant/s. We also welcome inquiries from individuals interested in serving as a session moderator or discussant to include a brief statement of interest and a short summary of work in oral history. Proposals are due October 1, 2021. (See below for more information.)

Some questions and themes we expect symposium participants may address include:

(Please note that we are open to other related questions and explorations.)

Whiteness and White Supremacy

- How should Whiteness be defined, and how do the deep structures and conventions of our practice reflect Whiteness, structural racism, and White supremacy?

- How might an interrogation of unexamined Whiteness be brought to bear on work in oral history? This might be done by assessing a past project or the curation of an existing collection or by considering the planning and implementation of a project currently under development. (Note: While we welcome case studies that audit specific projects, we would also like to see papers go beyond that.)

- How has work that has drawn upon existing collections reproduced racialized assumptions?

- What are some examples of projects that handled or represented racial dynamics, including Whiteness, in a creative, antiracist, or otherwise generative way?

Non-Western perspectives and approaches

- What has oral history learned from Indigenous, African American and other perspectives and approaches that fall outside the dominant Western paradigm?

- What patterns do we see in our own work that can be traced to BIPOC origins and models? What do these BIPOC origins and models have to teach us about the pitfalls of Whiteness and White Supremacy?

- How might specific insights, both theoretical and methodological, generated by the field of Critical Race Studies, help guide practical approaches to oral history?

- How and in what circumstances has oral history operated against the grain of prevailing racial assumptions?

- What can oral historians learn about power dynamics and reflexivity from research in the field of trauma studies?

Invisible Architecture

- How have the institutional and organizational structures underlying work in oral history been racialized? How has the way oral history has been funded and otherwise supported contributed to unintentional racial bias? How has the “history from below” approach perpetuated these biases? And how do White interviewers themselves perpetuate bias?

- Over its fifty-plus year history, how has the work of the Oral History Association been racialized or reflective of broader patterns of White supremacy? In what ways and to what effect has the association functioned as a gatekeeper for oral history and oral historians, including some practitioners, practices, and work, excluding others, through its various products and programs such as the Principles and Best Practices, annual meeting, and publication of the Oral History Review? How has the association addressed racial issues over time, to what effect?

- When and where is it appropriate for oral historians to think beyond our individual projects and consider the role of the institutions we work for in order to tackle structural racism?

Oral history and current events

- How are oral historians and the institutions and organizations with which we are affiliated responding to the current political moment? How might we respond more effectively?

- Oral history is by its nature a civic enterprise and a medium for public engagement. How can oral history mobilize anti-racist constituencies, create dialogue around difficult issues, and/or influence public opinion or policy?

- What are the limits of oral history in combating structural racism?

The deadline for proposal submissions is October 1, 2021.

Notification of acceptance: On or about November 15.

Submit proposals to:

In the subject line of your email, please write, “Last Name Symposium Proposal Submission” and send to: TRANSFORMATIVEORALHISTORY@GMAIL.COM. Proposals should be sent as an attachment in Word or PDF formats and not in the body of the email. Please include a cover page with your name, contact information, and brief bio.

Questions may be directed to:

TRANSFORMATIVEORALHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

Final papers should be submitted no later than April 15, 2022 in order to post them on the conference website for distribution to conference attendants by May 1, 2022.

Final papers should be between 5,000 and 7,000 words and include a bibliography.

Submit final papers to:

In the subject line of your email, please write, “Last Name Symposium Paper Submission” and send to: TRANSFORMATIVEORALHISTORY@GMAIL.COM. Proposals should be sent as an attachment in Word or PDF formats and not in the body of the email. Please include a cover page with your name, contact information, and brief bio.

*The Ad Hoc Group for Transformative Oral History is composed to date of the five panelists who contributed to the OHA’s 2020 conference session, “Is Oral History White?” – Benji de la Piedra, Jessica Douglas, Kelly E. Navies, Linda Shopes and Holly Werner-Thomas.

August 2021 OHC Book Club Pick: Let’s Talk About Hard Things by Anna Sale

Good news for all of you book club fans out there! The Oral History Center is pleased to announce the pick for our Summer 2021 Book Club: Let’s Talk About Hard Things by Death, Sex & Money podcast host, Anna Sale. Anna is also a podcast and audio instructor with the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism’s Advanced Media Institute.

And there’s more! Anna Sale will be joining us for our virtual book club discussion!

We’ll be welcoming Anna as our special guest on Tuesday, August 10, 2021 from 2-3pm PST via Zoom.

If you’d like to join, please send an RSVP to Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu. Once you’ve RSVP’d, Shanna will send you the Zoom information.

You can find Let’s Talk About Hard Things online, at your local bookstore, and at your local library. We look forward to seeing you in August!

From the OHC Archives: Zona Roberts and Learning to Walk Backwards

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

The pocket of Berkeley bounded by Telegraph and Shattuck avenues is generally considered to be quiet and uneventful. Colorful Victorian houses line the blocks, gray apartment complexes full of Cal students loom over sidewalks, and telephone lines crisscross over each other, dividing the sky into irregularly sized rectangles and diamonds. I spend a lot of time in this part of Berkeley. I have my favorite houses, my favorite trees, my favorite views in every direction. I have my favorite alleys and blocks and moments in its history. I can’t pick a single favorite former resident, but Zona Roberts is high on the list.

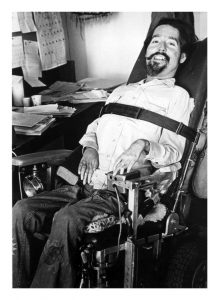

Zona existed in Berkeley as a mother before she existed here as a student. She lived with her sons Ed, Ron, Mark, and Randy in a pale green house she rented on Ward Street, a few blocks west of the hustle and bustle of Telegraph Avenue and a few blocks east of Shattuck. I often walk by her old house. It’s blue now, with red front steps, and it sits unassumingly behind a fence overgrown with flowers in the springtime. When Zona moved in, she had a ramp installed in the back to allow Ed to get inside. Ed Roberts, Zona’s eldest son and a political science major at UC Berkeley, was the first wheelchair user ever admitted to the school, and virtually nothing in the city was wheelchair accessible when he arrived on campus in 1962, including his mother’s home.

Ed Roberts

The green house, as it came to be known, acted as a sort of safe haven for the Roberts family and their friends. It was a family home for the community, not just Zona and her sons.

“It was a neighborhood of older families who’d lived there, a neighborhood of single-family homes, mostly, or two flats,” Zona said of the area, “The neighborhood was just changing as some of the older folks were dying off and some were moving away. A few younger people were moving in, but it was more or less an established neighborhood. But because of the racial composition and students in Berkeley, no one cared who went in and out of my house. The kids who came in or the Black students who visited and some lived, for a while, with me. There was no threat to their lives. There were none of those issues. It was just like a breath of fresh air to me. It was so nice not to have to worry about what might happen. I remember that vividly.”

Roberts Family

Zona, by all accounts, was an unflappable person. When she and her sons came to Berkeley, she was a recent widow, and had been Ed’s primary caretaker since he contracted polio and became a quadriplegic in 1953. She was a fierce advocate for all her sons and their needs and disliked being told what to do—she, as a learned expert in their likes and needs, felt that she knew best.

UC Berkeley promised a new world of opportunity for both her and Ed, when previously, his disability had meant neither of them was optimistic about what the future would hold, and her role as mother and caretaker left little room for imagining a life outside their home. But Berkeley was different; here, Ed was a student and leader, and eventually, so was she. In her oral history, when the conversation veered away from her time in Berkeley, she’d direct it back with references to the green house. The landscape of her college experience seemed to define it. She became acquainted with Berkeley alongside and behind Ed.

“One of the first days when I had taken Ed across and through campus, he was in a pushchair those days. He was quite tall and quite thin. We were going down into Faculty Glade and I had a hold of the back of his chair. It began to slip a little bit and I ran into a tree sort of deliberately to stop the chair, just the side of it, into this tree because I felt I was going to lose it. I don’t know whether my hands were sweaty, or the place was wet or what was happening. I think I finally learned how to do it backwards, where I’d walk down the hill backwards. I had better control.”

This anecdote, in my mind, speaks to the essence of Zona Roberts: ever present and adaptable to the needs of her son, caring and thoughtful, in the heart of Berkeley.

“In my senior year, I’d visit Ed up at Cowell. I remember one of the first times I walked through campus carrying my books, walked by Strawberry Creek, walking up to Cowell instead of coming in the station wagon from home or coming over to visit them. Here I was walking across campus on my way between classes and going up to visit and smiling a broad smile that I was now a student at Berkeley, also, and very proud of myself, and loving the campus and Strawberry Creek coming down through the middle of it. There’s some beauty in that Berkeley campus,” she said.

This feeling of reverence for Berkeley—for the atmosphere of casual intellectualism, for the exciting possibilities of being a student, for the sometimes-unbelievable natural beauty of the campus—is one I am intimately familiar with. I can only imagine how those feelings would be magnified for Zona, who, as a middle-aged widow and mother of four, never thought she’d live in Berkeley or become a student.

Zona was immensely proud to be a Berkeley student and to be Ed’s mother. She encouraged his involvement in activism and saw herself as an important backer of the disability rights movement; she saw herself as, first and foremost, an important backer of Ed.

“I saw my role at the office [UC Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living] as it became known as I did in Ed’s life, pushing Ed in front and being behind him,” she said of her involvement, “This was a place for people with visible disabilities to be visible, to be out in front. I found myself being in a supporting role, seeing that the office functions were going as smoothly as possible, seeing that there was food and heat and counseling and open doors and open access to information from us to the university and from the university to us. But somehow, we were in this together and it was a part of a wonderful movement. The time had come, and we were in the forefront of the movement and we were told this from all over the world. That was a glorious feeling. Hard work and glorious feeling.”

Zona Roberts

Zona Roberts worked hard to be the best mother she could be. Eventually, that meant becoming an integral part of a movement that was so much larger than any of them individually. If Ed Roberts was the father of the disability rights movement, Zona was the grandmother. She worked in the Center for Independent Living for years after its founding, and remains active in disability rights activism today, years after Ed’s death and well into her one hundred and first year of life.

I imagine the learning process of her activism was similar to learning to walk down the hill next to the Faculty Glade backwards, or modifying the old green house on Ward Street to make it accessible: sometimes slow-going, and certainly not without error, but always more than worth the trouble.

Crip Camp and Judy Heumann: Studies in Movement Snapshots

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

I watched the 2020 documentary Crip Camp to get a sense of Judy Heumann, the disability rights icon and architect of a movement that created a more accessible world. I had only recently read her oral history, conducted by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, and I was eager to learn more about the woman behind the words on the page. When she is first shown in the film, she is doing what I’ve learned that she does best: leading a group. She has a big voice and a bigger grin, and talks campers through their options for dinner later in the week. She’s already thought it through—she considered veal parmesan, but found the veal to be too expensive, so next on her list is lasagna, the suggestion of which elicits both cheers and groans from the crowd. She offers everyone a chance to make their case, and then takes a vote. Lasagna wins—barely. This vote, in its consequences, probably meant very little to Judy and very little to everyone else. But in my mind, it makes one thing clear: Judy didn’t make any decisions without considering and consulting the group. She cared what people had to say, and she listened. And so campers had lasagna, and eventually, thanks to her activism, disabled Americans had laws to protect them.

Crimp Camp provides a snapshot of the disability rights movement through the lens of Camp Jened, a summer camp for disabled children and teenagers that opened in upstate New York in 1951. Each summer, about 120 campers moved in for four to eight weeks. The camp, despite often being credited with changing the lives of its campers, had immense financial struggles and closed its doors in 1977, leaving its legacy in the hands of the many campers who passed through. Judy contracted polio and became paralyzed at 18 months old, and for every summer from ages 9 to 18, she was one of those campers. She credited her time at Jened with shaping her approach to activism and life generally.

Jened resembles the woodsy summer camps of my childhood, but it had more of a Summer of Love aura about it—the rec room was boisterous and the softball games were passionately played, but at Jened, counselors were hippies, campers fell in love, and the bunkrooms and mess halls overflowed with eager conversations about the state of disability rights and the world. It was in those conversations, Judy would go on to say, that she learned to listen to a group, lead a group, and speak as a part of a group. To Judy and the other campers, Jened was more than a camp: it was a place to be fully and truly oneself, a place to try out new politics, and often, a place to meet close friends and lovers (Judy even said she never dated outside of camp). It almost seemed sacred.

Jened is both a moment and an enduring feature in the history of the disability rights movement, and Crip Camp seeks to understand it as both: as a physical place, where people gathered and grew, and as a concept, a memory and idea that endured well beyond the summers it operated. Oral history, as a practice, seeks to accomplish something similar. It draws on memories of particular moments, the feelings that make something worth remembering, and unites those memories with broader historical narratives to give a complete picture of a life and a time. But I can’t help but wonder—what does it mean when a story continues after the taping is done? When the end of the recorded narrative turns out to be the midpoint of a real and full life?

Judy Heumann’s oral history focuses on her time UC Berkeley, where she received her master’s in Public Health, and the 504 sit-in of 1977, which she was critical in organizing. For 25 days, Judy and well over 100 disabled people occupied the San Francisco office of the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and demanded enforcement of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which stated that no institution receiving federal funding could exclude people on the basis of their disability. Judy’s activism in 1972 was critical to getting Section 504 written in the first place, and she and other disabled people were tired of it being completely unenforced—schools, cities, and buildings were still inaccessible despite the law’s promise. Schools lacked elevators to allow disabled students to get to their classrooms; sidewalks lacked defined dips in the corners and thus often forced wheelchair users to take inconvenient, circuitous routes to their destinations or left them stranded. In response, disabled people occupied government buildings across the country in protest. The San Francisco demonstration was the longest lasting and arguably the most successful, largely thanks to the motivating force that was Judy Heumann.

Judy Heumann

In Crip Camp, Corbett O’Toole, a disabled activist and one of Judy’s contemporaries at the Center for Independent Living at UC Berkeley, said that “we were more scared of disappointing Judy Heumann than we ever were of the FBI or police department arresting us.” This was because Judy served as the central organizing force of the occupation—she held down the fort, ensured people’s needs were met (no easy task when many occupiers required around-the-clock physical assistance), and negotiated with government figures to advance the cause. I’d be scared to disappoint her, too.

There’s no debate about her status as an organizing powerhouse. In the early days of the disability rights movement, everyone in her orbit seemed to recognize that she had a knack for getting people together, getting people to listen, and perhaps most crucially, getting people to act. Mary Lester, a staff member at the Center for Independent Living spoke about Judy in her own oral history and credited her with the movement’s expansion.

“Judy was the one who brought in deaf services and was the one who always wanted to expand the population we were serving. She was pushing us in those directions to broaden the coalition. She was a networker supreme,” she said, “Judy wanted to push CIL as far as it could go in terms of being a model and being a pioneer and bringing all of the different disability factions, if you will, together.”

Judy was meticulous and thoughtful in her activism; no stone went unturned, no idea went unexplored, and no voice went unheard.

“We had the civil rights aura, but we had the facts,” she said of the Independent Living Movement, which she helped develop in Berkeley, “I mean, I think the civil rights aura without the facts actually doesn’t get you where you need to be. But the facts without the civil rights perspective doesn’t necessarily get you there either.”

Berkeley, as a city and community center, played a critical role in shaping the 504 sit-ins and the disability rights movement more broadly.

“Well, you know Berkeley is a small community, period. And many of the people certainly at that time were activists. And you lived on the same block with somebody, or a couple of blocks away,” she said, starting to laugh, “And that’s just the way it is. It’s a town.”

UC Berkeley was to Judy and her friends what Jened had been to them in their youth. Crip Camp gets at this: many of Judy’s friends from her camp days eventually made the same westward journey that she did, and ended up in and around the UC Berkeley community. There, they took the community they’d built in upstate New York and turned to activism. Jened taught them the importance of their community; Berkeley taught them how to fight for it.

Judy Heumann recorded her oral history with UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center in 2007, decades after her time at Camp Jened and some of her most well-known organizing efforts. Since then, she’s lived nearly another decade and a half—enough time to feature in an Oscar-nominated documentary, host a podcast, produce a research paper on improving media representation of disabled people, publish a memoir, and work on advancing disability rights internationally as a special advisor to President Obama in the State Department.

She spoke about her international ambitions and hopes for the disability rights movement in her oral history, before Barack Obama was even the Democratic nominee for president; before there was even an inkling that her role as his special advisor on international disability rights would ever exist. In this way, oral history provides us with a window into her mind, a snapshot of a moment in the unfinished history of the disability rights movement. This, perhaps, is part of the value of an oral history conducted before the end of someone’s life—it reveals the in the moment motivations and thoughts behind future actions, and is definitionally more than just temporally distanced reflection or speculation about how and why something occurred.

Judy Heumann at the 2021 Academy Awards

In the same way that Crip Camp sought to capture multiple dimensions of Camp Jened and its legacy, looking at Judy Heumann’s oral history in light of the more recent years of her life allows for a complex and interesting portrait of her and her accomplishments. As a history major, the people I study often never lived to see the worlds that they created, so it is especially wonderful to know that Judy Heumann saw the disability rights movement from its inception to a piece of storied history behind the world as we know it now.

“But you know, you walk up Telegraph Avenue, you go to Rasputin’s, and you see this history of the disability movement, and the owner of the store proudly displaying history of the disability rights movement on a building,” she said in her oral history, “You see, I go into a restaurant yesterday and there are two young disabled people coming in from Berkeley sitting down and having lunch together. The waiter’s moving the chairs out, and I’m like, oh, I guess two people in chairs are coming. And these things are natural now, because there is such a large number of people here that the community itself has become more accepting. It’s normal.”

I am a student at UC Berkeley and I live a block from Telegraph Avenue; between me and Judy’s tangible legacy sits a sidewalk that slopes down at the corners for wheelchair access. The world is not perfectly accessible, and there is still much to be done to ensure that disabled people’s rights are protected, but I like to think about how my normal is the product of Judy’s life’s work.

From the OHC Archives: Linda Perotti, Apolitical Advocate

By Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

Linda Perotti didn’t mean to join a movement. She arrived in Berkeley a year after the Free Speech Movement got its raucous start on the steps of Sproul Hall, the university’s now-famous administrative building on the southern edge of campus, and she was more concerned with keeping up with her coursework than with any of the growing number of antiwar and civil rights movements that would come to characterize Berkeley in the late 60s.

“[T]he thing I remember most is the Sproul steps, just sitting there and watching people go by,” she said of her freshman year. She regarded herself as an observer, never a participant. But as these things tend to happen, a movement found Linda anyway.

As a freshman at Cal, Linda was surrounded by the energy of the movements unfolding across campus. Sproul Plaza seemed perpetually occupied by someone giving an impassioned speech about any number of political issues to a crowd of eager students, her male friends constantly fretted about being drafted, and sometimes, police vans and teargas would descend on campus, their motivations largely unbeknownst to her. On any given day, her Sproul people-watching might have included a lecture on the value of political speech on college campuses, a demonstration against the Vietnam War, or a march down Telegraph Avenue, which led from campus into the city. UC Berkeley, to her, was a thrilling, semi-utopic reprieve from a culturally homogenous childhood spent in Michigan and the San Fernando Valley; a place where everyone and everything could be reached on foot; a place where she could be an individual; a place where everyone was intellectually serious, but no one took themselves too seriously.

Sproul Plaza during the Free Speech Movement

Linda remained uninvolved in campus politics for her first two years at Cal, but that doesn’t mean she wasn’t paying attention to things happening around her.

“I remember one of the eeriest sights, when I really became aware of what a political hotbed Berkeley was,” she said of witnessing a stand-off outside her freshman dorm, just south of campus, “What turned out to be a SWAT team. They were all cops, just gathering, with shields and helmets and batons. I had never seen anything like that. It was extremely scary. Now if you saw that, you might just shrug and say, ‘Oh, something’s going on.’ But in 1965, it was a real phenomenon.” She didn’t have to be involved in a movement to understand that they were everywhere in Berkeley.

She moved to a new apartment on Ward Street at the beginning of the summer of ‘68—the summer of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, the Poor People’s Campaign, and Nixon’s nomination—and soon found herself spending a lot of time with the Roberts family, whose comings and goings via van and motorcycle she’d observed for weeks before discovering that one of the motorcyclists was her acquaintance, Mark Roberts. The small, green Roberts house was a peculiar one for a college town, and Linda was drawn to the fact that the Roberts family actually acted as a family unit. Linda had many friends, but they were just as independent as she; she didn’t yet have a family in Berkeley.

Zona Roberts and her sons were different. Zona zipped off to class on her motorcycle each morning, and there seemed to be a constant rotation of young people cycling in and out of the house.

“The whole family—they’re a very friendly family. Very, very friendly people. And just very unassuming. At the time, Zona was a student at Berkeley herself. Her husband had died a few years earlier. I don’t know how she did it financially. She was always on the edge, but somehow she managed,” Linda recalled.

She was attracted to the hum of energy radiating from the house and soon befriended Mark’s older brother Ed Roberts, the first wheelchair user admitted to UC Berkeley and the eventual father of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement. He suggested that she stop by Cowell Hospital and lend a hand. Cowell, while a fully functioning campus infirmary, also functioned as a dormitory of sorts for physically disabled students. It was unlike any program that existed anywhere else, and while Linda’s recollection of her early days there was hazy, she spent her summer on the northwest side of campus, doing odd jobs at Cowell.

Cowell Hospital

As a woman, the help she could offer was limited—only men lived in Cowell at that point, and she recalled that “the men only had other young men working for them,” so she found herself doing laundry, typing up various documents, pushing wheelchair users around campus, and hauling enormous pots of chili and spaghetti across campus for Friday night dinners. Gender continued to define Linda’s relationship to Cowell and the budding Disability Rights Movement writ large; to her, the politics of the movement were for the boys.

“I never was interested in the political aspects of it,” she said, “It was just a byproduct as far as I was concerned. I even used to laugh at the guys. See, ‘the guys.’ It just happened to be that way.”

This disinterest was not from lack of care, but rather what Linda described as a naturally apolitical disposition. It wasn’t as if she wasn’t also interested in the pro-disability rights causes “the guys” were organizing for; of course she was. She spent her days working at Cowell and with the leaders of the Disability Rights Movement, albeit never in the context of their activism.

“This was really good for me,” she said of her proximity to their activism, “because it suited my level of political interest or awareness.” To Linda, her work was most significant when it was on the ground and person-to-person. Someone else could handle writing to the Chancellor.

“I had gone through the Cowell Hospital movement where people got organized and found their own strength and actually made their demands in such a way that the university responded to them and actually established a program just to serve the physically disabled,” she recalled, “That was very interesting.”

In the fall of 1968, the Cowell Program admitted its first female resident, and just as he had earlier in the summer, Ed Roberts encouraged Linda to go on up and introduce herself. Perhaps, Ed thought, Linda could serve as this new resident’s attendant, and help her with day-to-day tasks like bathing and getting dressed for class. Cathy Caulfield, Cowell’s first female resident, arrived in time for the fall semester, and sure enough, Linda became one of her attendants. At the same time, Linda recalled, the conversations that would serve as the foundation of the disability rights movement started picking up on the third floor of Cowell, where the program residents lived. Something was in the air.

But Linda was focused on her work. She had never been an attendant before, and the job was demanding. She deeply cared about being a good attendant for Cathy, and even beyond that, she cared about being a friend to her. So Cathy taught her how to change a urinary catheter, and how to dress and bathe her, and in turn, Linda learned how to be caring and gentle and composed. Her experience was typical; none of the attendants had formal training beyond what the people they worked for taught them. Cathy soon became deeply involved in the political organizing happening on the third floor, and she and Linda became good friends.

“I didn’t see myself as part of an attendant group because the rest were guys, and they worked for the guys, and my two friends and I worked for Cathy, ‘the woman,’” Linda said, referring to her two close friends who also worked as attendants. Her focus was Cathy, not finding community with other attendants or Cowell residents, and to her, that was just as well.

The next few years of Linda’s life track nicely alongside the development of the Disabled Students’ Program (DSP) and the Center for Independent Living (CIL)—she stopped taking classes during what would have been her senior year, and spent a lot of time with the organizers behind DSP and CIL as the programs swelled in size and scope. Still, though, movement politics were uninteresting to her. She cared about streamlining attendant referral services—everything was still word of mouth—and developing peer counseling services for disabled students, and helping the organizers accomplish other goals that they had, but she understood her role to be primarily administrative.

Linda Perotti never thought of herself as an activist. Her work was work, even if that work was also groundbreaking and life-changing and empowering for more people than she ever probably knew she could reach. The Sproul steps that she remembered so fondly have since witnessed many more movements, and many more generations of students who have benefitted from the activism—and semi-passive support—of Berkeley students that came before them. Linda may not have meant to join a movement, and maybe she would contend that she never actually did, but she certainly made a difference—for Cathy and the other Cowell residents, for herself, and for the generations of Berkeley students that followed her.

Preserving Spaces and Stories with Save Mount Diablo

by Samantha Ready

Samantha Ready is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes during the Spring ’21 semester to help them prepare for their upcoming oral history project celebrating Save Mount Diablo’s 50th anniversary.

From Samantha: My name is Samantha Ready (she/her) and I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas. I am currently a third-year at Cal double majoring in Ethnic Studies and Geography with a minor in Race and the Law. Some of my favorite pastimes are hiking, traveling, and listening to Johnny Cash.

This semester, I had the privilege of joining the Oral History Center’s Save Mount Diablo Project as a background researcher under the mentorship of Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes. Despite growing up in the ‘Natural State’ of Arkansas, I didn’t learn much about environmental preservation. Coming into this research project, my personal definition of preservation was limited to the scope of society and culture. I’ve focused my studies on supporting and amplifying the perspective of marginalized communities, because they are often overshadowed by dominating narratives. Working on this project taught me about two important things that were missing from my definition of cultural preservation: land conservation and oral histories. Because I learned about the deeply rooted connections between environmental preservation and personal narratives, I now see clearly how important these facets are to the preservation of cultures and histories from all voices.

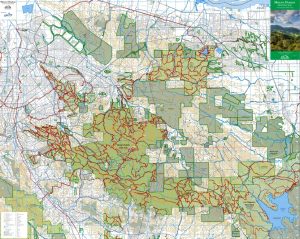

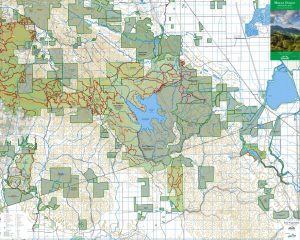

Save Mount Diablo (SMD) is a nationally accredited land trust organization and has been working to conserve the land around Mount Diablo in the East Bay since 1971. The preservation of natural land is a main goal of SMD, and has thus far been achieved through consistent advocacy, dedicated stewardship, thoughtful land-use planning, and educational programs. Mount Diablo’s biodiversity, historical and agricultural significance, and natural beauty are important to both the area’s general quality of life and natural resources. SMD works to provide ways for people to interact with the environment at Mount Diablo through recreational opportunities that consistently protect the region’s natural resources and open spaces, such as their Discover Diablo public hiking program, educational classes with local schools, and the annual Four Days Diablo backpacking trip through the mountain. Below are two maps of 2020 The Mount Diablo Regional Trail Map, which both feature the Diablo Trail that spans across the entire regional area. Of the 338,000 total acres shown between both maps, more than 120,000 acres have been preserved and protected thanks to Save Mount Diablo. Seth Adams, SMD’s Land Conservation Director, says that “No other map shows all of the Diablo area parks in a unified design and in regional context. The map illustrates what has been accomplished and what private lands still need to be protected.” (SMD website) The first map features Mount Diablo State Park and surrounding parks, and the second features Los Vaqueros and surrounding parks.

Mount Diablo & Surrounding Parks:

Los Vaqueros & Surrounding Parks:

Image Credits: maps produced by Save Mount Diablo

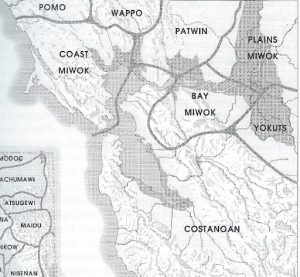

In my research about Save Mount Diablo, it became apparent that working alongside surrounding community members -including SMD membershipSMD membership, various outside organizations, and political leaders/institutions- has been vital to maintaining their mission of preserving the environment. My first point of interest here was learning more about which communities and organizations SMD has worked with, how, and why. I immediately thought of Indigenous communities connected with Mount Diablo. Bev Ortiz, a Native American historian and SMD newsletter contributing author, wrote an article entitled “Mount Diablo as Myth and Reality: An Indian History Convoluted,“ in which she describes the mountain’s cultural and religious significance to Native Nations. Mount Diablo is meaningful for the Nations of the Miwok, Maidu (Nisenan), Ohlone (Chochenyo), Pomo, and Wintun Nations. Ortiz connected with members from these Native Nations in her work of preserving their cultural connections with Mount Diablo, from whom she learned about these connections, which included creation stories of several Nations. Creation stories are the original forms of oral history, and have helped preserve Indigenous cultures for thousands of years. Below is a map by Mount Diablo State Park of languages spoken by Native Americans from the region of Mount Diablo.

Image Credit: Mount Diablo State Park

Save Mount Diablo has often recognized Native cultural connections with Mount Diablo throughout its efforts to protect the mountain, such as in SMD Director of Land Programs Seth Adams’ timeline of the History of Mount Diablo, SMD’s stance to protect Tesla Park, and SMD Executive Director Ted Clement’s event to discuss SMD’s work with Indigenous communities to preserve cultural resources. Native American culture strongly connects with the environment, as they were the Earth’s first caretakers and the first to sustainably manage the world’s natural resources. Indigenous Nations around the world have maintained that stewardship of their ancestral homelands would be the first step to restoring their relationship with the land after colonization. In this sense, the inclusion of Native communities in environmental preservation would also aid in the preservation of their culture(s). To me, Save Mount Diablo’s work with Native communities thus far indicates their sincere recognition of how important the preservation of Native connections with Mount Diablo are to preserving the region’s land. Though there is definitely recognition, I remain curious as to the extent Indigenous communities are directly involved in SMD’s stewardship and conservation of Mount Diablo lands.

Another part of the community Save Mount Diablo works within is the political sphere. SMD has been heavily involved in, or at least taken stances on, several ballot measures throughout its50 years of fighting for environmental preservation. SMD also spends a lot of time tracking proposals by potential developers to ensure they follow the environmental rules and protections set by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) of 1970. The main purpose of CEQA is to prevent and decrease environmental damage by developments and to allow a public decision-making process, which enables community members to discuss their concerns regarding development projects’s environmental effects. This work has led to SMD’s working with local political leaders and alliances with conservation networks in order to defend Urban Limit Lines (ULLs) against developers of preserved space in the Mount Diablo region. These ULLs preserve and protect open spaces, and are often threatened by developers, corporations, and some politicians. In their encouragement of public engagement with these issues, SMD provides email templates to send to local and state political leaders about issues at hand. Save Mount Diablo has been successful in these political methods of environmental preservation largely due to their active involvement and communication with outside persons, organizations, and institutions. Through its years of interactions with political representatives, public organizations, and parks districts, I wonder how, if at all, SMD’s standing as a private organization has affected the outcomes of these interactions. Additionally, I’m curious about how situational outside influences affected these interactions.

Image Credit: EnvironmentalScience.org

When learning about stories of the past, even those of organizations like Save Mount Diablo, it’s important to think about the perspective from which the story is being told. Learning about oral history played a big role in helping me realize that because of its practice to amplify and preserve individual voices so as to learn about their personal and lived experiences of historical occurrences. UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center (OHC) continues this mission across a variety of projects, including in this Save Mount Diablo Project. An ultimate goal of the SMD oral histories is to understand how the organization promotes a thoughtful relationship between people and the environment to inspire positive growth for the natural land and society as a whole. The background research I was able to contribute this semester barely scratched the surface of this story, and the rest lies in the stories soon to be told in the oral histories of Save Mount Diablo.

Learning about notable contributions of Save Mount Diablo to land conservation and environmental preservation taught me about how intersectional preservation is with most, if not all, facets of life. Not only do they work to conserve land that is sacred both biologically and culturally, SMD consistently provides recreational and educational resources for teaching and learning about the environment and the importance of preserving it. Now, it’s time for the preservation of Save Mount Diablo’s stories.

OHC’s Director’s Column: April 2021

Martin Meeker’s April 2021 Director’s Column

With the month of May fast approaching, I have been thinking a great deal about motherhood in general and my Mom in particular. Growing up, Mother’s Day was a big deal around my house — and my Mom wasn’t shy about letting us know that she appreciated the day off (from work at the office and home) and didn’t mind a little fuss being made for her. And she deserved it. My two sisters and I put her (and my Dad) through the paces. The entry of her kids into adulthood wasn’t so easy, either, with our cultural and political clashes, divorces, and career uncertainty. But our family persisted, largely due to my Mom, who willingly, or perhaps expectedly, assumed a peacemaker role. Lately, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the family more closely together with regular Zoom reunions and an active, if usually silly, text group.

This week will mark the first time I get to lay my eyes on my mom in about 18 months — too long, considering that she’ll turn 80 this year. So, I’m thinking about the many, often difficult, roles that mothers are compelled to play and how those roles have changed. And, with COVID, have become more fraught and challenging.

When I begin to ponder something, arcane or universal, I’ll often turn to the OHC archive of 4000 oral histories with an eye to hearing first person accounts of real experiences on a given topic. Thankfully, our archive is replete with mainstream and remarkable stories of women who reflect on the joys, the work, the meaning, and the trials of motherhood.

Beverly Hancock Bouwsma, who was interviewed in 2001 for the UC Berkeley History Department project as a faculty wife, mused throughout her oral history of familial division of labor and the work of motherhood — in her case raising five children. When asked by OHC historian Ann Lage, “Did you enjoy motherhood?” Bouwsma replied, “Oh, I loved it. I did. I mean, sometimes it’s the worst thing in the world, but I always had a nice time with the children and cared desperately about them growing up. It seems like I didn’t, because when I hear now what they did, and I never knew about it, it seems like I must have been an awful mother. But I remember, at the time, I did what I thought you should do, and I really cared a lot.” This brief response articulates the love and frustrations and ambiguity many narrators in our collection reveal about motherhood — their recollections are rarely pat, especially when given the opportunity to reflect and speak at length.

Bay Area businesswoman Margaret Liu Collins, who was interviewed in 2011, recalls having two children with a husband who was abusive. Eventually the marriage ended and she raised the kids on her own, which kept her busy trying to build a business during the daytime, attending prayer meetings in the evening, and soccer games on the weekends. Then tragedy struck: her seven-year-old son was hit by a drunk driver. Collins recounted the moment, “It was 1979 sometime in October. I heard a siren going past my house because our house was on Belmont Canyon Road. The school was just across the street. We moved there from Cupertino because I had to travel a lot to Texas to do all my real estate, as well as go to Hong Kong and meet all my clients. I heard footsteps running onto the deck of our driveway, and somebody banged on the door. I had a really bad feeling that something was happening. The girl next door came and said, ‘Mrs. Liu, your son has been hit by a van and has been taken by the fire department to a hospital nearby’.” She continued, “When I went to Mills Hospital, he was in a coma. The doctor said he might never wake up. I was in pain. He was a brilliant child. It was my child. How could he pre-decease me? He had a whole future ahead. He had always lived with such enthusiasm, such curiosity. He loved people, and everybody loved him. He was generous. He was kind. He was giving. He could always solve problems. I still remember at that moment, I was feeling very sad.” Several months of treatment, uncertainty, and fear followed. Eventually, her son emerged from his coma and made a full recovery. She thanked God for his blessings but it was her devotion and love that brought her son back from the brink.

As well as recollections from women about their own experiences of motherhood, OHC’s collection contains thousands of memories of mothers by daughters and sons. Shirley Henderson, who was interviewed for our Rosie the Riveter / World War II Home Front project, remembered growing up in Berkeley in the 1930s admiring her mom for engaging in service activities outside the home: “My mother was the original community volunteer. She was a very capable and bubbly, outgoing woman. She did Girl Scouts; she was indefatigable at the church. I wonder what churches are going to be like when there are no more women to work as volunteers, which is about where the churches are now, almost. She ran a Sunday school class, a very large class of girls, because the girls were all so enthusiastic about the class that they brought their friends. My mother had them from the fourth grade through the twelfth grade, the same girls for that whole time. My mother had a very good third ear, and some of those girls had family troubles, and they were lucky to have my mother. I can remember being jealous of them because my mother gave them more attention than she gave to me. But I didn’t need it. That’s, of course, the other half, the flip side.”

These passages represent the slightest hint at the extensive archive of stories of mothers and motherhood in the OHC collection. While OHC has never embarked on an “oral history of motherhood,” by using our search tool, you can construct your own such archive by uncovering many more of these remarkable narratives of exceptional mothers. And we hope you do this Mother’s Day and beyond.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

One Shot for Gold: Developing a Modern Mine in Northern California

by OHC Emeritus Historian/Interview Eleanor Herz Swent

An account of the creation of a modern, environmentally sensitive mine as told by the people who developed and worked it, from the University of Nevada Press Spring 2021 catalog.

In connection with this, Swent will be presenting her work as part of the American Society for Environmental History’s Environmental History Week. Her panel will be on Earth Day, and more information can be found here.

……………………………………………………………………………………..

As this was written, the Mars Rover Perseverance landed, thanks in part to research conducted at the mine in Napa County that was the subject of this book.

This is a different kind of oral history – not the life of a person, but of a mine – California’s most productive gold mine of the twentieth century. Between 1985 and 2002, the mine produced about 3.4 million ounces of gold, transforming the state’s poorest county and changing the industry around the world. OHC’s Knoxville/McLaughlin project, the basis for this book, comprised forty-eight interviews conducted over ten years.

In 1965, James William Wilder had a successful earth-moving and hauling business and decided to try mining. His research led him to buy the Manhattan mercury mine in the Knoxville District of Napa County. “We called it One Shot. If we don’t make it on this one, we’re out of the mining business.”

In 1974, Willa Baum, director of what is now the Oral History Center, was advisor for an Oakland neighborhood history project endowed by the NIH, and Eleanor “Lee” Swent was a volunteer, interviewing residents of the Fruitvale district and Chinatown. When Willa learned that Lee had spent most of her life living in mining towns, and that both her father and husband were mining engineers, it seemed that the time had finally come to document one of the most important aspects of California history – mining. In 1986, with the support of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers [AIME], the Mining Society of America [MSA], and the Woman’s Auxiliary to the AIME [WAAIME], the oral history series on Western Mining was established, and from then until 2001, Lee conducted 46 full-length oral histories with significant figures in the industry. They were men, with three exceptions: Helen Henshaw, the wife of the president of Homestake Mining Company; Catherine Campbell, geologist, editor, and widow of Ian Campbell, California State Geologist and Director of the California Division of Mines and Geology; and Marian Lane, aka Winnie Ruth Judd, wife of a mine doctor.

In 1978, a young geologist working for Homestake Mining Company, California’s oldest corporation, explored the One Shot mercury mine. “It was just a joy to look at. It has to be one of the best exposed, zoned gold deposits that ever was. It was just a type example of the mercury-hot-springs-gold association; a classic example.”

It was accessible only from Lake County, at that time, the poorest in the state, with a median household income of $5,266 and a population of 19, 548. By 1989, when the gold mine was in production, the income had about quadrupled, to $21,794, and in 1990 the population was 50,631. With funding support from Homestake, a community college branch was subsidized to train local workers, a hospital expanded its services, telephone and electric utility service was extended, and roads were paved. Many of these improvements were lasting benefits to the county.

The life of the mine was projected to be about twenty years, and most of the key players were available for interviews. It was a rare opportunity to document the discovery, development, and reclamation of a mine while it was happening. In 1991, the Knoxville District/McLaughlin Mine oral history project was launched.

Between then and 2005, forty-eight interviews, from two to seventeen hours long, were conducted with the owner of the One Shot Mine; Homestake officials and a wide range of employees; supervisors and planners from Napa, Lake, and Yolo counties; the Lake County school superintendent, local historians, mercury miners, merchants, and ranchers, as well as some of the most vocal opponents of the mine. Their voices help to tell the story of the mine and a changed community.

An engineer from New Zealand was manager for the construction. “This was the biggest nonunion construction project that had ever been done in California. It was thirty-odd miles long and we did 3 million man-hours. We engineered the dickens out of everything.” A rancher’s wife appreciated her job as a mine surveyor. ”I’ve learned invaluable stuff on the computers that I had never had any experience with before.”

“One Shot for Gold” documents the effort to win public support and to obtain an unprecedented number of 327 permits from the federal, state, regional, and local agencies that had jurisdiction. Homestake engineers tell of their research from Finland to South Africa to develop the method of high-pressure oxidation to recover gold from ore without polluting air or water; it has now been copied around the world.

The mine was named for Donald Hamilton McLaughlin, chairman emeritus of Homestake and a regent of the University of California. In 1961, his wife, Sylvia Cranmer McLaughlin, founded Save San Francisco Bay, one of the first grassroots environmental organizations, that sparked national awareness and led to the first Earth Day, celebrated in San Francisco in 1974. This movement forced Homestake to incorporate environmental protection into its business model. From the beginning, plans for the mine included reclamation as the Donald and Sylvia Nature Reserve, part of the University of California Natural Reserve System. He died at the age of 93 on December 31, 1984, and Sylvia McLaughlin dedicated the mine to him in a ceremony on Saturday, September 28, 1985. The natural reserve named for them is a fitting coda to the story of a modern mine: extracting one precious resource, gold, and preserving another, the natural environment, its air and water.

In 2001, the mine geologist recalled, “NASA Ames research showed up at the door to look at samples of rock from our hot springs terraces that contained fossilized bacterial remains, evidence for the most primitive live on earth, to think through how landers on Mars would go about sampling and looking for evidence of life.”

“One Shot for Gold” begins with the mercury mine at Knoxville and ends with the Donald and Sylvia McLaughlin Nature Reserve. On February 11, 2021, the director of the reserve wrote, “Since around 2010, we’ve had a team from NASA and biogeochemists from various universities working on understanding the bacteria that live in geologic water deep inside serpentine rock, and how those studies can inform exobiologists where to look for life on other celestial bodies.”

As this was written, the astrobiology Rover Perseverance landed on Mars, ready to hunt for signs of life like those preserved at the depths of the Mclaughlin mine.