Arts & Humanities

Black History Month 2024

This February, check out our 2024 Black History Month picks from cultural contributions, relatable stories, and historical moments.

James McBride

Sadeqa Johnson

Donovan Ramsey

Matthew Delmont

Jonathan Abrams

Zadie Smith

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

Charmaine Wilkerson

Tembe Denton-Hurst

Il Tolomeo: rivista di studi postcoloniali

Hard to imagine the UC Berkeley Library as one that may soon not be able to afford new journal subscriptions but for better for worse, that’s where we are heading with serials reduction projects such as the one we undertook last year. It’s a good thing thing the open access movement is still gaining traction. It’s also a good thing universities like the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice are boldly choosing to publish their journals and some of their books this way.

Il Tolomeo: rivista di studi postcoloniali first saw the light of day in 1995, thanks to the work of a group of postcolonial scholars at Ca’ Foscari. The journal publishes peer-reviewed articles, reviews, interviews, and previously unpublished original contributions in the fields of francophone, anglophone and lusophone literatures. It investigates the postcolonial literary phenomenon in all its manifestations, but is particularly interested in contributions which take a comparative, interdisciplinary approach: dialogues between literature and the arts, investigations of hybrid forms such as comic strips and cinema, research which links literary studies with the social sciences, or innovative approaches such as digital and environmental humanities.

For its next issue, Il Tolomeo invites all interested scholars to send their contributions for the upcoming 2024 issue (no. 26). The issue will be divided into a generalist section (on any theme) and a thematic section dedicated to asylum, refugees and postcolonial literatures. The deadline for submitting complete contributions is May 20, 2024.

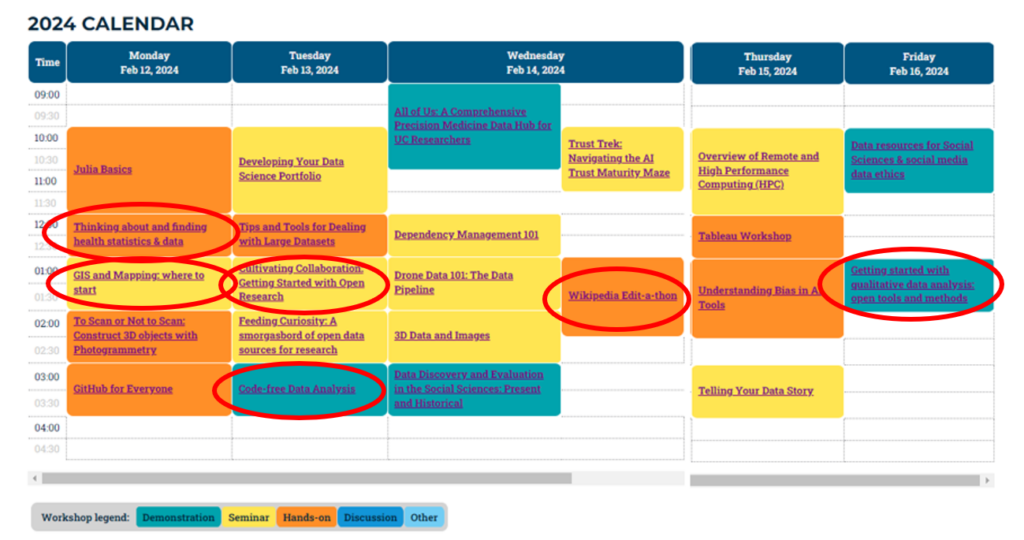

Wikiphiliacs, Unite! (At our Wikipedia Editathon, on Valentine’s Day, 2024)

I am a proud Wikiphiliac. At least, according to the Urban Dictionary, which defines Wikiphilia as “a powerful obsession with Wikipedia”. I have many of the signs it warns of, including “accessing Wikipedia several times a day…spending much more time on Wikipedia than originally intended [and]… compulsively switching to other Wikipedia articles, using the hyperlinks within articles, often without obtaining the originally sought information and leaving a bizarre informational “trail” in his/her browsing history” (but that last part is just normal life as a librarian).

How else do I love Wikipedia? Let me count the ways! As a librarian, I always approach crowd-sourced information with a critical eye, but I also admire that Wikipedia has its own standards for fact-checking, and in fact some topics are locked to public editing. It takes its mission very seriously. It also has an accessible and neutral tone. Especially when I want to learn about a technical topic, it can give me a straightforward and helpful way to approach it. I also use it pretty routinely as a way to look at collections of sources about a topic; when I was a medical librarian, I was asked for data on the condition neurofibromatosis, and at that time the best basic links I found were in the references for the Wikipedia article. Last and maybe most importantly, the fact that anyone can edit is a huge strength…with challenges. Wikipedia openly admits its content is skewed by the gender and racial imbalance of its editors, and knowing this is part of approaching it critically, but it also means that IT CAN CHANGE, and WE CAN CHANGE IT.

Given that philia, a word taken from Ancient Greek (according to the philia Wikipedia article), means affection for or love of something, it’s fitting that our 2024 Wikipedia Editathon is part of UC’s Love Data Week, and happens on Valentine’s Day. If you would like to learn to contribute to this amazing resource, and perhaps even help diversify its editorial pool, we can get you started! There isn’t yet a Wikipedia page on Wikiphilia, but maybe you could create one! There already is a podcast series…

If you’re interested in learning more, we warmly welcome you and invite you to join us on Wednesday, February 14, from 1-2:30 for the 2024 UC Berkeley Libraries Wikipedia Editathon. No experience is required—we will teach you all you need to know about editing! (but, if you want to edit with us in real time, please create a Wikipedia account before the workshop—information on how to do that is on the registration page). The link to register is here, and you can contact any of the workshop leaders with questions. We hope you will join us, and we look forward to editing with you!

NOTE: the Wikipedia Editathon is just one of the programs that’s part of the University of California’s Love Data Week 2024! Don’t forget to check out all the other great UC Love Data Week offerings—this year UC Berkeley Librarians are hosting/co-hosting SIX different sessions! Here are those UCB-led workshop links, and the full calendar is linked here:

Thinking About and Finding Health Statistics & Data

GIS & Mapping: Where to Start

Cultivating Collaboration: Getting Started with Open Research

Code-free Data Analysis

Wikipedia Edit-a-thon

Getting Started with Qualitative Data Analysis

PhiloBiblon 2024 n. 1 (enero): Vulnus amoris: vulnerabilidad más acá del Tratado de amor atribuido a Juan de Mena

Salvador Cuenca

Valencia

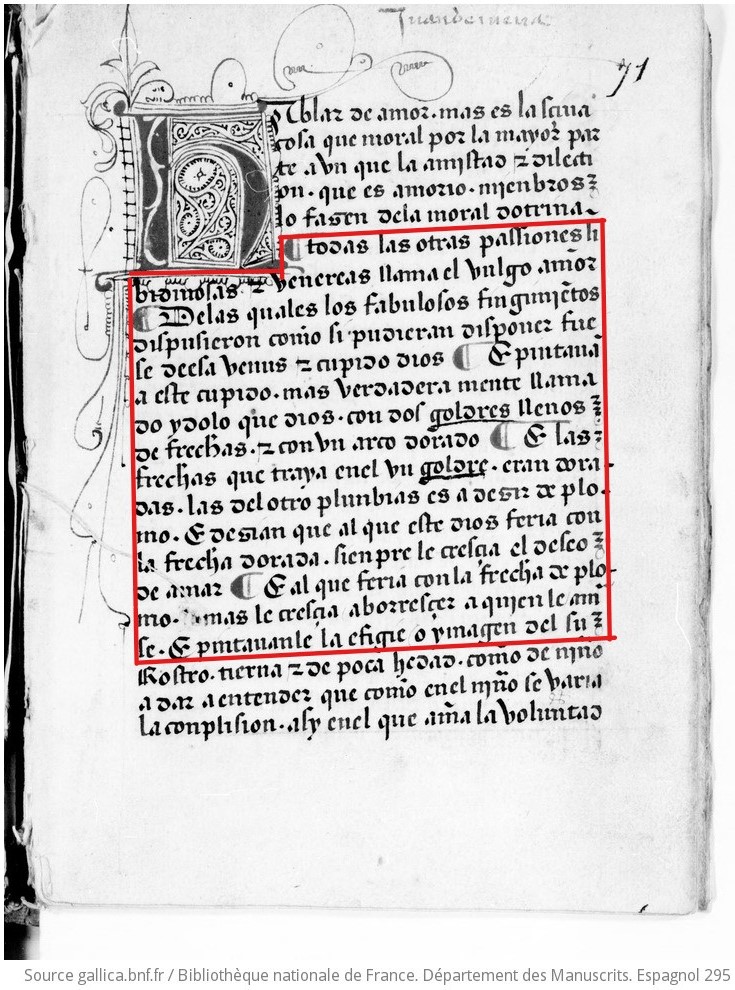

En una reciente visita a la Biblioteca Nacional de Francia pude consultar el manuscrito que contiene el Tratado de amor (BnF esp. 295) [BETA manid 2478], atribuido por una mano moderna a Juan de Mena (1411-1456).

Las notas allí tomadas y la celebración de la natividad de Jesús propician la redacción de este texto acerca del tópico del vulnus amoris en particular y acerca de la vulnerabilidad humana en general. Esta entrada de blog, por tanto, se articula entre las proyecciones de un texto tardomedieval y sus todavía posibles lecturas y lectores del siglo XXI; como si nos halláramos en medio de un juego de espejos que nos sitúa entre el vulnus amoris causado por las flechas de Cupido y nuestra propia vulnerabilidad, como entre los infinitos reflejos de nuestras figuras en los espejos de un ascensor. Seguiremos, pues, el sentido de las flechas de oro y de plomo de los goldres de Cupido, disparadas desde un códice cuatrocentista hasta nuestro espíritu navideño y hasta su reinterpretación desde las aportaciones de la neurobiología a la descripción de las relaciones humanas. Entre el siglo XV y el siglo XXI, se multiplicarán nuestros reflejos.

1. En las celebraciones navideñas, la vulnerabilidad del niño Jesús nos podría hacer recordar el niño que todos hemos sido. Todos hemos sido traspasados por flechas de oro que nos han llevado a perseguir el afecto y a captar la atención de aquellas personas de las que hemos dependido y de las que, en algunas ocasiones, para bien o para mal, todavía dependemos. Esa vulnerabilidad nos ha hecho ser humanos, animales sociales y políticos. Ese primer vulnus amoris de nuestra niñez lo causaría, desde la perspectiva adoptada para escribir este texto, otro dios con forma de niño: Cupido.

En el inicio del Tratado de amor se reproduce su imagen:

Todas las otras passiones li|ibidinosas

て venereas llama el vulgo amor

⸿Delas quales los fabulosos fingimjentos

dispusieron commo si pudieran disponer fue|se

deesa venus て cupido dios ⸿ E pintauan

a este cupido. mas verdadera mente llama|do

ydolo que dios. con dos goldres llenos

de frechas. て con vn arco dorado ⸿ E las

frechas que traya enel vn goldre . eran dora|dos.

las del otro plunbias es a dezir de plo|mo.

E dezian que al que este dios feria con

la frecha dorada.sienpre le cresçia el deseo

de amar ⸿ E al que feria con la frecha de plo|mo.

mas le cresçia aborresçer a qujen le amªse

No sería Cupido, sin embargo, el dios de las tres maneras básicas de querer—“amistad, dilectión, que es amorío, e amor” (Valero 2001: 35)—, sino solo de una de ellas, a saber, de la pasión de amor. Por tanto, no sería el arquetipo de las relaciones escogidas e igualitarias de la amistad ni de las relaciones dilectas del amorío de los superiores para con sus inferiores, como el amorío del Creador para con sus criaturas, de la madre para con sus hijos o de “la yegua cuando pare el potrico” (Valero 2001: 47). ¿Qué tipo de pasión se establecería con el amor de Cupido? Una pasión “libidinosa e venérea” entre inferiores y vulnerables, que a su vez “se subdivide en dos partes: la una es en amor líçito e sano; la otra en no líçito e insano” (Valero 2001: 36). El amor lícito es el conyugal, al cual “non solamente la dotrina christiana alaba e bendize, mas aun la dotrina [de la] gentilidad” (Valero 2001: 36). La vieja solución pagana al desafío del desorden que puede producir el deseo libidinal, expresada por el mito clásico de Cupido y Psique, se cristianizaría con el amor conyugal del matrimonio lícito. Dicho de otro modo, el Tratado de amor subraya la coincidencia entre la solución gentil y la cristiana al alabar las bondades del matrimonio para solucionar los trastornos ocasionados por el vulnus amoris. Pero esa solución no cautiva la atención del autor del Tratado; son más interesantes, en cambio, los problemas que surgen del otro miembro de la bipartición, a saber, de la parte del amor no lícito. El Tratado además subraya que el amor, aparte de aumentar la vulnerabilidad de los amantes, provoca que estos no puedan escoger el tipo de pasión que les embarga, es decir, que no puedan elegir si persiguen o si son perseguidos, si son atraídos o atraen. De aquí que el modo de vulnerabilidad no sea elegido y de aquí que podamos entender la imagen del “amador çiego” como un trasunto de una voluntad débil que no elige o como—y aquí va la primera intersección de literatura y neurobiología—una motivación que nos impulsa a actuar desde determinadas áreas del sistema límbico y que escapa al control racional del córtex prefrontal, en el cual se concentran los circuitos cerebrales conectados con los procesos de la elección deliberada. Dicho de otro modo, la deliberación se puede entender como un proceso de la corteza cerebral que controla los impulsos procedentes de las zonas más internas del encéfalo, como se puede inferir a partir de la lectura de “Decision-Making and Consciousness” (Kandel et alii 2021: 1392-1419).

La pasión amorosa, en suma, se liga con el sistema límbico, la impulsividad irracional y la vulnerabilidad humana a través de la imagen literaria de los dos goldres de flechas de Cupido, unas de oro, otras de plomo: “E dezían que al que este dios fería con la frecha dorada, siempre le cresçía el deseo de amar. E al que fería con la frecha de plomo, más le cresçía aborresçer a quien le amase. E pintávanle la efigie o imagen del su rostro tierna e de poca hedad, como de niño, a dar a entender que como en el niño se varía la conplisión, así en el que ama la voluntad.” (Valero 2001: 35)

Por ello, el Tratado de amor equipara la herida de la pasión amorosa con la carencia infantil de juicio y con la debilidad de la voluntad o incontinencia, en consonancia con algunas doctrinas aristotélicas divulgadas en ambientes cortesanos ibéricos por el Compendio de la Ética nicomáquea (ca. 1463-64) [BETA texid 1294]. En efecto, su descripción de la incontinencia como debilidad de la voluntad proporciona un ejemplo coetáneo de la problemática latente en el arranque del Tratado de amor: “continente solamente es dicho el que finca e permanece en recta razón e elección. E incontinente es su contrario” (Cuenca 2017: 151). Sin embargo, el amor hace variar la razón de tal manera que impide la deliberación y sus efectos, a saber, las elecciones racionales, e imposibilita, por consiguiente, la práctica de los hábitos electivos que son las virtudes morales, tal como se explica en el capítulo 5 del libro segundo del Compendio: “Capítulo quinto pone tres notificaciones de virtud. La primera, que virtud es perfección de la cosa. Segunda, que es mediedad entre dos extremos. Tercera, que es hábito electivo.” (Cuenca 2017: 51)

De acuerdo con esta cita, podemos indicar que la inclusión de la virtud en la lista de las once causas de amor que, según el Tratado, “despiertan e atrahen los corazones a bien querer” es paradójica. Es decir, si en el arranque del Tratado se estipulaba que la pasión de amor es ciega e irresistible, después se argumenta lo contrario, a saber, que “como el camino del amante sea libertad para descoger lo que más le plaze, el hábito electivo de amor viene en ábito de elegir antes al virtuoso que a un otro” (Valero: 37-38). Aquí el Tratado no es estricto en el uso de la terminología filosófica y parece que copia irreflexivamente el sintagma “hábito electivo”, porque el término ético más adecuado para referirse al hábito virtuoso—y, por ello, electivo, en relación con la selección activa del mejor compañero—sería “amistad” y no “amor”, cuyo uso se restringiría a la pasión irresistible, o sea, no escogida, no selectiva, pasiva (Cuenca 2019). Es como si las flechas doradas de Cupido no cegaran al herido por ellas, como si el único “amante çiego” fuera aquel magullado por las flechas de plomo, o como si las flechas doradas activaran la selectividad y las plúmbeas fomentaran la pasividad de la pasión. ¿Cómo podemos entender la paradoja del vulnus amoris de las flechas doradas?

2. Gracias a las investigaciones de David J. Anderson (Californa Institute of Technology) sobre las conexiones neuronales que ponen en marcha nuestras interacciones como animales sociales, podemos reinterpretar el gozo de los heridos por las flechas doradas, o sea, el gozo provocado por la vulnerabilidad selectiva o por la vulnerabilidad que escoge. Anderson, especialista en las funciones del hipotálamo, nos permite entender la paradoja con la que hemos concluído el apartado anterior, a saber, la paradoja que resulta de combinar la herida y el gozo, la pasión del amor y la selección activa del amante virtuoso.

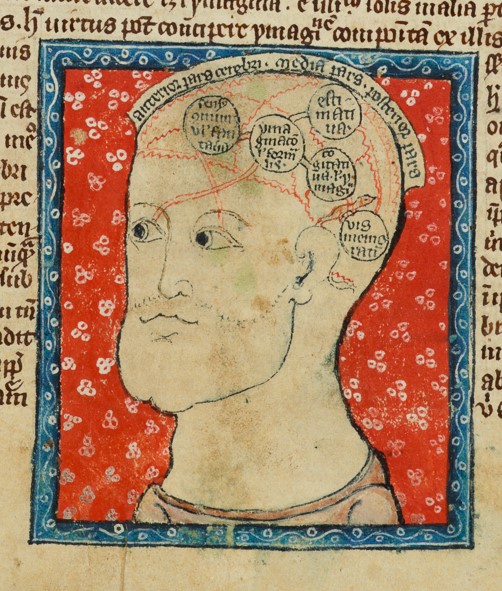

Todos los animales poseen un repertorio de conductas instintivas que pueden ponerse en práctica sin una enseñanza previa, es decir, que, desde la perspectiva en este texto adoptada, pueden manifestarse sin una elección racional y, por ende, asemejarse a las conductas descritas e identificadas con la etiqueta literaria de la pasión amorosa o vulnus amoris. Según Anderson, no se sabe aún si estas conductas están mediadas por circuitos neuronales diferenciados anatómicamente y/o genéticamente. Sus investigaciones, a partir de las imágenes de las conexiones neuronales del hipotálamo del ratón, concluyen que las conductas que impulsan a establecer vínculos con otros especímenes están modeladas por determinadas experiencias sociales—en humanos podríamos añadir “culturales”. De tal manera que las mismas neuronas (Esr1+: Oestrogen receptor 1-expressing neurons) de una área concreta del hipotálamo (VMHvl) controlan tanto el apareamiento como la dominación y agresión en los roedores machos (Anderson et alii 2017). Si damos el salto mortal de ratones a hombres y hacemos el ejercicio de aplicar estas investigaciones al tópico de las flechas de Cupido, podemos intuir que su disparo indiscriminado podría describir la conducta innata que a todos nos impulsa a establecer vínculos sociales, o sea, nadie elige las flechas que le hieren, las doradas o las plúmbeas, pero todos estamos expuestos a alguno de sus tipos de herida. Es decir, todos estamos cableados con los mismos circuitos neuronales que nos hacen someternos al influjo de Cupido. Ahora bien, ese influjo está moldeado por las experiencias sociales y los modelos culturales, de manera que las mismas neuronas pueden estar involucradas en las conductas de la seducción y persecución activa provocadas por las flechas doradas y en las conductas de aversión y evitación provocadas por las flechas plúmbeas. Resaltemos una curiosa coincidencia: la medicina medieval localizaba en un único ventrículo de la media pars cerebri la sede de la facultad estimativa, encargada de las conductas de persecución y de evitación, de manera semejante a la actual localización en el midbrain de los circuitos conectados con las conductas de fight or flight asociados al hipotálamo.

Tomás de Aquino, basándose en el Liber de anima de Avicena (I, 5 y II, 2), proporciona uno de los listados más conocidos de los sentidos interiores en Summa Theologiae, Iª, q. 78, a. 4: “Avicenna, in suo libro de anima, ponit quinque potentias sensitivas interiores, scilicet sensum communem, phantasiam, imaginativam, aestimativam et memorativam”. El dominico describe que la facultad estimativa es imprescindible para explicar las conductas animales de buscar/querer y de huir/evitar, como el huir de la oveja cuando ve al lobo: “necessarium est animali ut quaerat aliqua vel fugiat, non solum quia sunt convenientia vel non convenientia ad sentiendum, sed etiam propter aliquas alias commoditates et utilitates, sive nocumenta, sicut ovis videns lupum venientem fugit, non propter indecentiam coloris vel figurae, sed quasi inimicum naturae”. Subrayamos, también en este mismo artículo de la Summa, que el Aquinate explicita que la medicina medieval localizaba en la media pars capitis la facultad estimativa –cogitativa en los humanos– : “alia animalia percipiunt huiusmodi intentiones solum naturali quodam instinctu, homo autem etiam per quandam collationem. Et ideo quae in aliis animalibus dicitur aestimativa naturalis, in homine dicitur cogitativa, quae per collationem quandam huiusmodi intentiones adinvenit. Unde etiam dicitur ratio particularis, cui medici assignant determinatum organum, scilicet mediam partem capitis”. (Tomás de Aquino: 1889)

Volviendo a las investigaciones de Anderson, podríamos pensar que, aunque sean las mismas zonas del hipotálamo las involucradas en los procesos de persecución y aversión, en ellas se podrían activar circuitos neuronales distintos—como ha probado el profesor de CalTech en relación con los circuitos neuronales activos en las conductas sexuales de los roedores machos, que son distintos de aquellos activos en las conductas de dominación. Es decir, aunque la conducta masculina de montar y dominar sea muy parecida a ciertas conductas sexuales, se activan circuitos neuronales distintos en cada una de ellas, aun estando localizados en el hipotálamo todos esos circuitos. Podríamos pensar, volviendo al tópico del vulnus amoris, que la conducta de dominar y herir y la conducta de seducir y amar están muy cerca la una de la otra, aun siendo diferentes.

Ahora podemos responder a la pregunta formulada al final del segundo apartado: no elegimos nuestra anatomía, no escogemos tener circuitos neuronales que puedan encender un ánimo propenso a sentir el amor; lo único que podemos escoger en algunos casos es si orientamos esos circuitos del hipotálamo hacia personas virtuosas. Dicho de otro modo con la terminología del Tratado de amor, no elegimos ser heridos por las flechas de Cupido; lo único que podemos escoger, si nos ha perforado una flecha dorada, es orientar nuestra persecución hacia una persona virtuosa o que reúna alguna de las otras diez condiciones que motiven una constante persecución, ya que “muchas cosas se vençen por el seguimiento que en otra manera non se acabarían” (Valero 2001: 44). El que la seguía antes la conseguía, aunque en los últimos años ya no es así: primero con el paradigma del “no es no” y después del “solo sí es sí”. Podemos estar asistiendo, quizás, a una de esas experiencias sociales que modelan la conducta y cortocircuitan los impulsos procedentes del hipotálamo, gracias a la actividad deliberativa del córtex prefrontal.

3. Lo interesante del Tratado de amor es que muestra cómo la cultura bajomedieval ya diferenció el tipo de interacciones sociales del herido con las flechas doradas de aquellas del herido con las flechas plúmbeas. Las flechas doradas mueven a perseguir y las plúmbeas a evitar. La paradoja que hemos pretendido explicar con este breve texto es que las flechas de plomo no nos hieren, sino que nos hacen invulnerables y, por tanto, menos humanos. Sin embargo, esa invulnerabilidad es muy dolorosa, porque nos aísla y nos mueve a evitar las relaciones que nos hacen ser más humanos: las relaciones del amor. De aquí surge una última paradoja expresada por el tópico del vulnus amoris : todos somos propensos a un determinado tipo de herida, a un modo de vulnerabilidad, incluso aquellos que anhelan la invulnerabilidad. La dulce herida se abriría en la carne perforada por la flecha dorada y la herida amarga, en cambio, magullaría la dura piel contusionada por la flecha plúmbea. La invulnerabilidad, en conclusión, resultaría paradójicamente más dañina y dolorosa que la dulce vulnerabilidad infantil. Por eso adoramos a los niños, y no solo en Navidad.

Obras citadas:

Anderson et alii 2017: David J. Anderson, Ryan Remedios, Ann Kennedy, Moriel Zelikowsky, Benjamin F. Grewe, Mark J. Schnitzer: “Social behaviour shapes hypothalamic neural ensemble representations of conspecific sex”, Nature, 550: 388-92.

Cuenca 2017: Salvador Cuenca (ed.), Compendio de la Ética nicomáquea. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza.

Cuenca 2019: Salvador Cuenca, “Φιλία › amor, amicitia › ¿amor, amistança, amicicia o amistad? Las traducciones de φιλία en las traslaciones hispánicas de la Ética a Nicómaco en el siglo XV”. Cahiers d’études hispaniques medievales, 42:85-95.

Kandel et alii 2021: Eric R. Kandel, John D. Koester, Sarah H. Mack, Steven A. Siegelbaum (eds.), Principles of Neural Sciences, 6th edition: McGraw-Hill.

Qualiter caput hominis situatur. Cambridge University Library, Ms. Gg.1.1, ff. 490r-491r.

Roman de la Rose. National Library of Wales, Ms. NLW 5016D.

Tratado de amor. Bibliothèque national de France, Ms. Espagnol 295, ff. 71r-84v.

Valero 2001: Juan Miguel Valero (ed.), ¿Juan de Mena? Tratado de amor. En Tratados de amor en el entorno de la Celestina (Siglos XV-XVI), coord. Pedro M. Cátedra. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal España Nuevo Milenio: 31-49.

Tomás de Aquino 1889: Corpus Thomisticum. Sancti Thomae de Aquino Summa Theologiae

Revamped Guides for French/Francophone and Italian Literatures

A recent overhaul of the two literary research guides for French and Francophone Literatures and Italian Literature & Criticism first created quite a long time ago will improve navigation and discovery in these vast print collections. Over the course of the past year, we have critically reviewed the former guides, weeded outdated resources, and replaced them with more current content with links to digital resources when available.

These two literature research guides are now benefiting from the LibGuides platform, which makes it much easier to revise than the former PDFs. Each guide is structured by sections for article databases, general guides and literary histories, reference tools, poetry, theater & performance, and literary periods. They interface seamlessly with related guides published by the UC Berkeley Library. For example, on the home page of each LibGuide, there is a prominent link to the lists of recently acquired publications in both French and Italian, making it even easier to stay current on new books in any particular call number range.

Because the guides are much easier to update, they encourage user interaction and invite community suggestions for inclusion (or deletion).

If you have time over the winter break, please take a whirl and let us know what you think. We’ll be unveiling a similar guide for Iberian Literatures & Criticism this spring!

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 7 (diciembre): Subastas y literatura medieval (II). Nuevos manuscritos: Sumario del despensero; Historia del Rey Don Pedro, de Gracia Dei; Libro del juego de los escaques; y la Historia de los hechos de los cavalleros de Xerez de la Frontera

Como aguinaldo navideño, ofrecemos a lectores y lectoras de nuestro PhiloBlog una continuación de la primera entrada, publicada en marzo de 2021, en la que dimos a conocer algunas obras literarias encontradas en catálogos de subastas. En aquella ocasión describimos la existencia de una nueva Crónica de Enrique IV manuscrita (BETA manid 6089) y de tres impresos quinientistas: el Carro de las donas de Eiximenis traducido al castellano (BETA copid 9237) e impreso en 1542; la Crónica ocampiana (BETA texid 1141) de 1543; y las Siete Partidas alfonsíes (BETA copid 9240) impresas en 1576. En esta segunda entrega vamos a ofrecer otra vez un breve resumen de las últimas fichas incorporadas a nuestro proyecto procedentes de subastas y ventas de librerías de las que hemos tenido noticia.

La primera de ellas es una nueva fuente manuscrita de la obra que recibe el título de Sumario del despensero (BETA texid 2851), que se encuentra la venta en la Librería Anticuaria El Camino de Santiago (Catálogo 76, febrero de 2021, nº 85). A pesar de contar con una moderna edición (Jardin, 2013), el enorme laberinto ecdótico del Sumario todavía está por descifrar al completo, sobre todo lo que respecta a sus adiciones posteriores, así como a sus segundas y terceras redacciones, con la dificultad añadida del cotejo de supresiones o modificaciones del texto. La importancia de esta versión resumida del modelo narrativo cronístico emanado del escritorio alfonsí es su amplia presencia a lo largo de todo el Cuatrocientos, lo que a su vez conforma una magnífica prueba de la buena salud de la que gozaban estas recopilaciones abreviadas siglos más tarde de que fueran compuestas (Gómez Redondo, HPMC, III, 2098-2099).

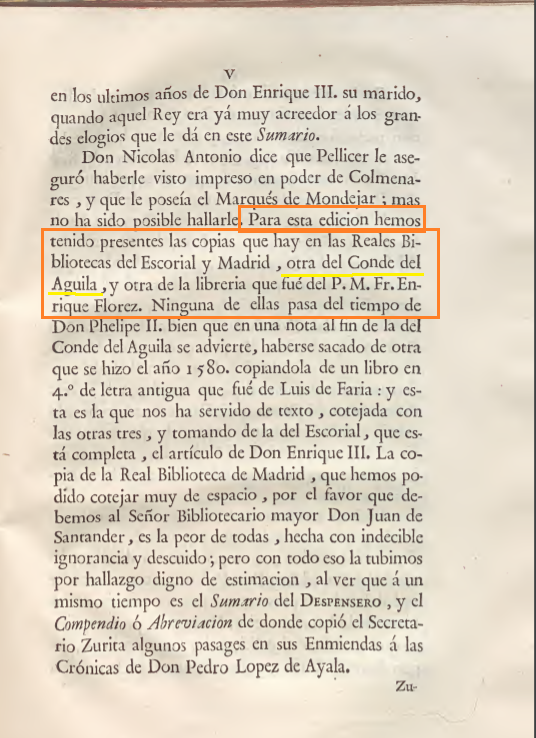

El códice del Sumario del despensero a la venta en la librería leonesa se presenta, como suele ser frecuente, con otra obra más: la Historia del Rey Don Pedro (BETA texid 1547), escrita por Pedro de Gracia Dei (BETA bioid 2995), un autor cuya obra y biografía conforman uno de los mayores laberintos de la literatura castellana de los siglos XV y XVI, a pesar de los recientes esfuerzos recorriendo sus vericuetos efectuados por González de Fauve, Las Heras y De Forteza (2006); por Mangas Navarro (2020a; 2020b); y por Perea Rodríguez (2024). En la descripción del catálogo del manuscrito—del cual no disponemos de imágenes—nos indica un detalle esencial para trazar su procedencia si lo relacionamos con la introducción de la primera edición moderna (1781) del Sumario del despensero, efectuada por Llaguno Amirola. En ella (p. V, reproducida más abajo), el erudito alavés dijo haber cotejado, entre otros, un códice perteneciente al conde de Águila, Juan Bautista de Espinosa Tello de Guzmán (BETA bioid 8671). El manuscrito a la venta en la Librería Anticuaria El Camino de Santiago indica que se copió en Sevilla en el año 1775 y tuvo como antígrafo a aquella misma copia utilizada por Llaguno Amirola procedente de la biblioteca del conde de Águila.

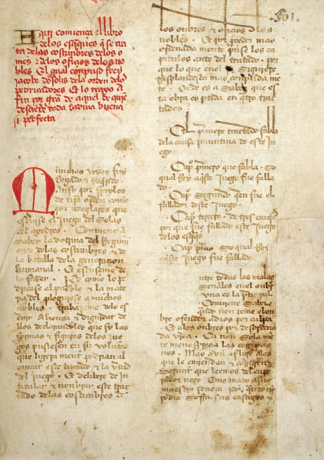

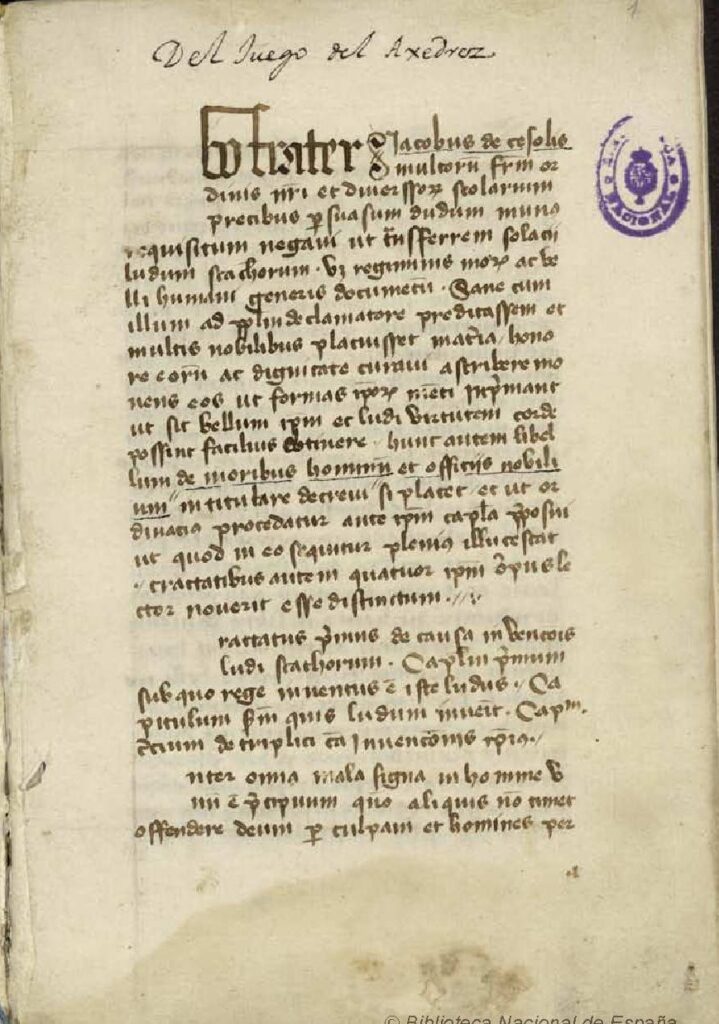

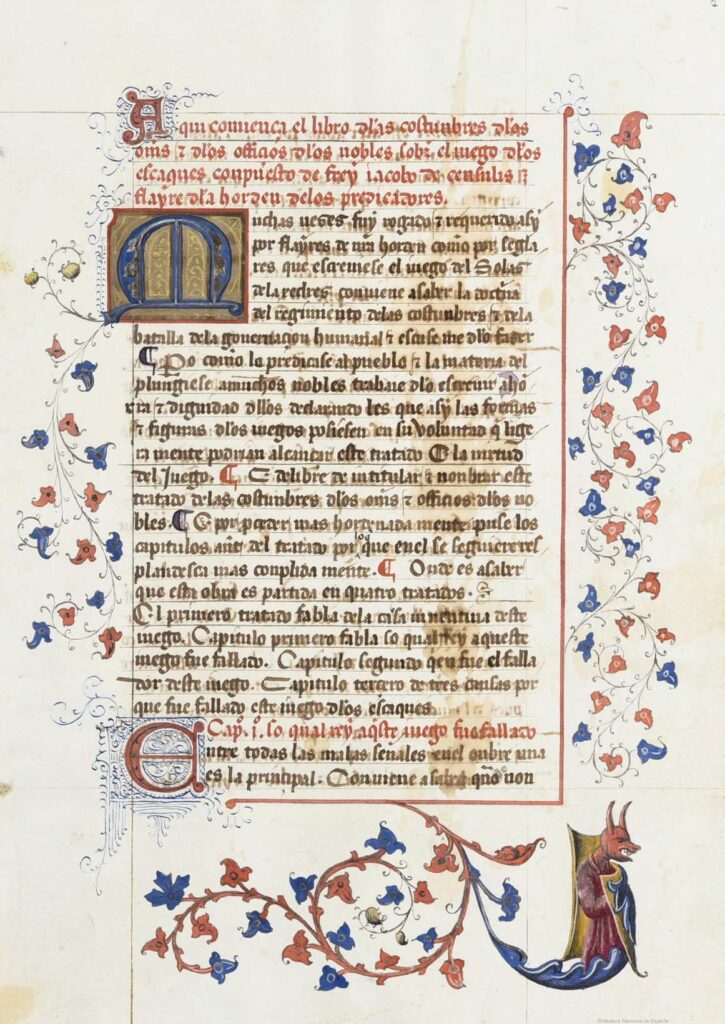

El siguiente manuscrito, del que sí disponemos de imágenes, pertenece a la madrileña sala de subastas El Remate, y fue anunciado en su catálogo de junio de 2023. Se trata de una nueva y hasta ahora desconocida copia del Libro de los esquaques (BETA CNUM 16143), que a veces aparece con un título más largo: Libro de las costunbres de los ommes e de los offiçios de los nobles sobre el juego de los escaques (BETA texid 11294). El códice subastado que aquí describimos (BETA manid 6461), de tamaño folio, se encuentra en muy buen estado de conservación, pues apenas contiene dos o tres folios con pequeñas manchas de humedad que en ningún modo impiden el disfrute de la lectura del contenido.

Estamos ante una traducción al castellano del más importante tratado ajedrecístico de la Baja Edad Media en su vertiente románica occidental. Se atribuye su redacción al italiano Jacopo da Cessole, o Jacobus de Cessolis (BETA bioid 3290), que era la forma que llevaba su nombre en el tratado original, escrito en latín. Compuesta en el primer tercio del siglo XIV, la obra circuló con bastante profusión por toda Europa, como se deduce del amplio número de ejemplares de esta obra registrados por Patricia Cañizares Ferriz y Montserrat Jiménez San Cristóbal en la base de datos MANIPULUS. De hecho, la Biblioteca Nacional de España ha conservado varios de estos manuscritos del De ludo scachorum, entre ellos uno (MSS/8919) que tal vez sirviera como texto base para acometer algunas de las traducciones que hemos conservado. No obstante, téngase en cuenta que hay otros estudios, como los de Bataller Catalá (2000), que sugieren la atractiva hipótesis de que, en realidad, los romanceamientos castellanos de esta obra no fueron traducidos directamente del latín, sino que se basaron en una traducción previa ya existente del latín al catalán.

Gran parte del éxito del De ludo scachorum se debió a que, en realidad, al margen de describir las destrezas del juego del ajedrez, también era un manual de buenas costumbres de la aristocracia medieval, de ahí que muy pronto fuera traducido a otras lenguas. Por lo que respecta al castellano, se han conservado dos diferentes traducciones: la primera, la ya mencionada Libro de las costunbres de los ommes e de los offiçios de los nobles sobre el juego de los escaques (BETA texid 11294); y una segunda, de la que solo hemos conservado una traducción parcial del tercero de los tratados (BETA texid 3781). Esta última, la versión incompleta, se conserva junto a obras de Diego de Valera y Juan Rodríguez del Padrón en el manuscrito B2705 de la Hispanic Society neoyorquina (BETA manid 4024). De la versión completa conocemos dos manuscritos más: el primero es el códice 80 de la biblioteca de la Fundación Ducal de Alba (BETA manid 4880), mientras que el segundo es el RES/299 de la Biblioteca Nacional de España (BETA manid 6080).

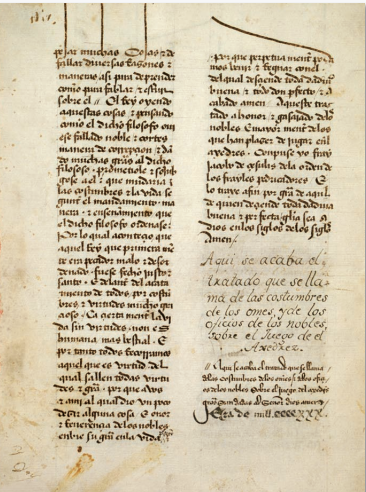

A falta de una más minuciosa exploración y cotejo de los textos contenidos en las fuentes, el manuscrito subastado por El Remate parece pertenecer a la misma tradición textual que los dos códices antes mencionados, el de la BNE y el de la Fundación Duque de Alba, si bien presenta un estado más tosco, sin tan profusa decoración como el de la BNE ni tan esmerados adornos gráficos y caligráficos como el de la Biblioteca ducal de Alba. Pese a este menor interés artístico, el manuscrito de El Remate aporta un dato fundamental para avanzar nuestro conocimiento de cuándo se realizó la traducción al castellano, puesto que está fechado en la “era de mill. cccc. xxx.”, tal como se observa al final de la columna de la derecha de la siguiente imagen.

Como es sobradamente conocido, a la calendación en era hispánica hay que restarle 38 años para obtener la equivalencia en nuestro actual sistema de calendación, el de la era cristiana. Por lo tanto, el manuscrito estaría fechado en 1392, que es cuando la traducción ya se habría completado. Hasta ahora, se pensaba que había sido traducido mucho después, hacia mediados del siglo XV, conforme a la habitual tendencia de la crítica literaria medieval hispánica en hacer más tardías las fechas de traducciones de lo que en realidad son.

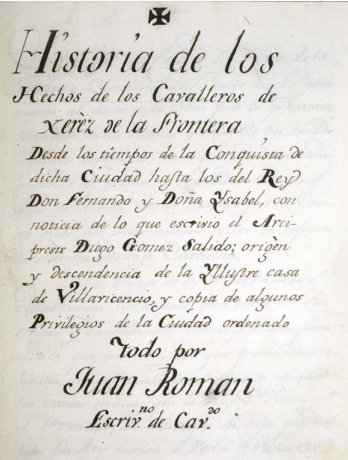

El último manuscrito al que nos referiremos en esta entrada también ha sido subastado por El Remate y lo más inmediato que hay que destacar de él es que, aparentemente, se trata de una obra que ha estado en paradero desconocido desde el siglo XVIII: la Historia de los hechos de los cavalleros de Xerez de la Frontera, que aparece con el nº 205 en el catálogo de subastas 239, correspondiente al mes de julio de 2023.

En su edición y estudio de El libro del alcázar, el profesor Abellán Pérez afirmó la existencia de un manuscrito del arcipreste local, Diego Gómez Salido, que en su momento fue muy utilizado por el medivalismo hispánico por su aparente contenido coetáneo a los tiempos medievales. Sin embargo, se perdió la pista de este libro entre 1705 y 1710. ¿Se trata del códice subastado por El Remate? Para asegurarse de que es, en efecto, el manuscrito de Gómez Salido, habría que contrastar su contenido con el del códice M/37 de la Biblioteca Municipal de Jerez de la Frontera. Parece bastante factible que puedan tener las mismas obras, sobre todo por las referencias que se hacen en ambos manuscritos a cierta genealogía sobre el linaje Villavicencio que se añadió con posterioridad a la primigenia redacción. El códice que reposa hoy en la librería pública jerezana ha sido recientemente restaurado, según informa Rafael de Leonor Molina en este artículo, y fue donado a la biblioteca por Pedro Gutiérrez de Quijano y López, que a su vez lo compró a Carmen de Cala, viuda de Juan Cortina de la Vega, conocido político y alcalde de Jerez de la Frontera en 1909. Es evidente que son de distinta procedencia, puesto que el subastado por El Remate, de 362 folios en total y con encuadernación holandesa del siglo XIX, presenta un exlibris de Feliciano Ramírez de Arellano (1826-1896), marqués de la Fuensanta del Valle, hermano de otros no menos destacados bibliófilos, los Ramírez de Arellano cordobeses. El marqués es conocido en el mundo de la erudicción hispánica decimonónica por haber sido durante muchos años, junto a José Sancho Rayón y a Francisco de Zabálburu, editor de la Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España.

Por nuestra parte, solo esperamos a que los expertos se pongan de acuerdo sobre los contenidos de los últimos dos códices comentados para incorporar su contenido de creación medieval a nuestra base de datos y asignarlos los correspondientes identificadores. Pero eso será ya el año próximo, el mismo en el que deseamos a nuestros lectores y lectoras la mayor de las felicidades.

Óscar Perea Rodríguez

(PhiloBiblon BETA – University of San Francisco)

Obras citadas

Abellán Pérez, Juan. El Libro del Alcázar. De la toma de Jerez a la conquista de Gibraltar. Siglos XIII-XV. Jerez de la Frontera: EH Editores, 2012.

Bataller Catalá, Alexandre. “Les traduccions castellanes del Liber de moribus de Jacobus de Cessulis“, en Actas del VIII Congreso de la Asociación Hispánica de Literatura Medieval, eds. Margarita Freixas et al., Santander, AHLM, 2000, I, pp. 337-52.

Cañizares Ferriz, Patricia (dir.) ELME: «Los exempla latinos medievales conservados en España» (2016-2023).

El Camino de Santiago. Obras impresas y manuscritas. Católogo de Librería Anticuaria nº 76 – Febrero de 2021.

El Remate Subastas. Catálogo 15 de junio de 2023.

González de Fauve, María Estela; Isabel Las Heras; y Patricia de Forteza. “Apología y censura: posibles autores de las crónicas favorables a Pedro I de Castilla”. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 36.1 (2006): 111-44.

Gómez Redondo, Fernando. Historia de la prosa medieval castellana, III: Los orígenes del humanismo. El marco cultural de Enrique III y Juan II. Madrid: Cátedra, 2002.

Jardin, Jean-Pierre (ed.) Suma de Reyes du Despensero. París: e-Spania Books, 2013.

Leonor Molina, Rafael. “La restauración del manuscrito denominado El libro del alcázar.” Revista de Historia de Jerez 16-17 (2014): 31-50.

Llaguno Amirola, Eugenio de (ed.) Sumario de los Reyes de España, por el despensero mayor de la reina Leonor. Madrid: Antonio de Sancha, 1781.

Mangas Navarro, Natalia. “La figura de Pedro de Gracia Dei: un bosquejo biográfico.” Estudios Románicos, 29 (2020a), pp. 297-318.

––– “Nuevas fuentes para la poesía de Pedro de Gracia Dei.” Revista de Cancioneros Impresos y Manuscritos, 9 (2020b), pp. 44-75.

Perea Rodríguez, Óscar. “El Libro de los pensamientos variables como ejemplo de utopía y disidencia en el siglo XV.” Cuadernos del CEMyR 32 (2024): 105-29.

CANCELLED Book Talk Sunday December 3rd from Art History Faculty Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson, Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art, will discuss her new book, Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Color, Join, Face , with Leigh Raiford, Professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies, at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive on Sunday, December 3rd at 2pm. Click the link for more information.

From the publisher’s website:

“A daring reassessment of Louise Nevelson, an icon of twentieth-century art whose innovative procedures relate to gendered, classed, and racialized forms of making

“Here is a book that is not only a transformative study of a single artist but also a record of the scholar’s own labor—and her devotion.”—Artforum

In this radical rethinking of the art of Louise Nevelson (1899–1988), Julia Bryan-Wilson provides a long-overdue critical account of a signature figure in postwar sculpture. A Ukraine-born Jewish immigrant, Nevelson persevered in the male-dominated New York art world. Nonetheless, her careful procedures of construction—in which she assembled found pieces of wood into elaborate structures, usually painted black—have been little studied.

Organized around a series of key operations in Nevelson’s own process (dragging, coloring, joining, and facing), the book comprises four slipcased, individually bound volumes that can be read in any order. Both form and content thus echo Nevelson’s own modular sculptures, the gridded boxes of which the artist herself rearranged. Exploring how Nevelson’s making relates to domesticity, racialized matter, gendered labor, and the environment, Bryan-Wilson offers a sustained examination of the social and political implications of Nevelson’s art. The author also approaches Nevelson’s sculptures from her own embodied subjectivity as a queer feminist scholar. She forges an expansive art history that places Nevelson’s assemblages in dialogue with a wide array of marginalized worldmaking and underlines the artist’s proclamation of allegiance to blackness.”

Celebrating more than 150 years of World Languages at Berkeley

New banners celebrate 150+ years of Berkeley’s prominence in teaching world languages

At least 60 languages — from Mongolian and Old Norse to Polish, Catalan, Ancient Egyptian, Arabic and Biblical Hebrew — are taught at UC Berkeley, one of the nation’s top institutions for the breadth and depth of its world languages program. A growing emphasis also is being placed at Berkeley on revitalizing and preserving endangered languages, most of them spoken by Indigenous peoples.

To help honor more than 150 years of global languages at Berkeley, 63 colorful banners will begin flying throughout campus today, and for the next 18 months, that feature facts about the campus’s language programs, as well as 21 bilingual and multilingual faculty members, students and alumni.

Among the messages on the banners:

- Collectively, undergraduates at UC Berkeley speak more than 220 different first languages.

- More than 500 language learning classes are taught at Berkeley annually.

- More than 6,000 Berkeley students enroll in those classes each year.

- In 1872, the first endowed chair in the UC system was created — for the study of East Asian languages at Berkeley.

- Students at all UC campuses can take online African language classes at Berkeley, which is well-known for Amharic, Igbo and Swahili instruction.

Reposted from Berkeley Letters & Science 10/25/23

See also: https://artshumanities.berkeley.edu/celebration-world-languages-uc-berkeley

Graphic Narrative Art by Emily Ehlen from OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

Below are ten graphic narrative illustrations created by artist Emily Ehlen that she drew from stories and themes in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project, recorded by the Oral History Center, or OHC.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and for Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork below, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories. To save a digital copy of any illustration below for fair use, right click on the image and select “Save Image As…” The text description that accompanies each illustration below aims to provide accessibility for the visually impaired in lieu of Alt-Text limitations, which does not easily accommodate graphic narrative images. In a separate blog post, you can learn more about the artist Emily Ehlen and her processes while creating these dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators.

Artist’s statement

Emily Ehlen’s illustrations for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project convey compelling narratives and imagery, with impactful shapes and color, by crafting traditionally and translating images into digital pieces. She uses text and imagery to balance the composition and support storytelling elements. Her work encompasses themes of identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. The collection navigates the impact and experiences of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and its effects on future generations.

WAVE by Emily Ehlen

This image titled WAVE consists of two panels. The top panel depicts text that relates to the number of generations of Japanese descents surrounding a family portrait using barbed wires as arrows. The text is in romanized Japanese and kanji. It reads: “Issei,” meaning first generation; “Nisei,” meaning second generation; “Sansei,” meaning third generation; “Yonsei,” meaning fourth generation; and “Gosei,” meaning fifth generation. The bottom panel depicts a large wave and guard tower behind barbed wire with text above that reads, “Your generation is just one part of the wave, and you do your best to build what you can for the next generation in your family.”

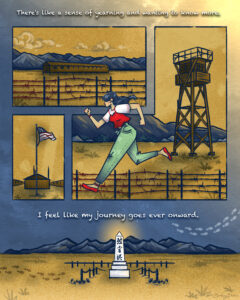

MANZANAR by Emily Ehlen

This image titled MANZANAR consists of four different panels. Each panel depicts a part of an incarceration camp and features barbed wire, the American flag, and the buildings in the camp. Above the top panel there is text that reads, “There’s like a sense of yearning and wanting to know more.” In the middle right panel, a woman in a red top layered over a white T-shirt and green pants runs towards the left of the image. The bottom panel depicts the cemetery monument at Manzanar National Historic Site, with Japanese kanji written on top, which reads, “I REI TO,” or “soul consoling tower.” Below the bottom panel there is text that reads, “I feel like my journey goes ever onward.”

STORIES by Emily Ehlen

This image titled STORIES consists of four panels. The top panel depicts a growing boy talking to his mother. An incarceration camp appears behind the mother. Above this top panel, the text reads, “My mom would not speak of things in camp. Maybe she didn’t want to or couldn’t at the time. It wasn’t ’til I was older did she begin telling me stories of camp.” Under this top panel, the text reads, “I got to know more about my mom, about a part of her life when I wasn’t there.” Two middle panels follow, depicting a green puzzle piece and crying eyes behind barbed wire. The text between these panels reads, “The missing piece she kept. The sadness she concealed.” In the bottom panel, tears from the eyes above fall into a plant on the ground that is growing. The text on this panel reads, “Talking about it didn’t make the pain disappear, but letting her experiences come to light brought a place for healing.”

TEACHER by Emily Ehlen

This image titled TEACHER consists of four panels. The top left panel shows a male teacher next to a chalkboard. The text on the chalkboard reads, “In middle school, we were learning about the Holocaust, and our teacher was telling the whole class like, ‘Well, Jewish people were put in camps…'” The top right panel depicts a raised hand with text that reads, “And I was like, ‘Wait, my grandmother was put in a camp.’ So I raised my hand.” The middle panel depicts a girl sitting at a desk, a male teacher standing, and a large crack between them. On the left of the panel, the girl says, “My grandparents were put in a camp, but they were put in a camp by America.” The text in the large crack reads, “And there was this awkward silence.” The teacher responds, “Well, we didn’t kill people.” The word “kill” has a red strikethrough on it. The bottom panel depicts the girl at the desk alone in the dark. The text reads, “I remember that as the first time I felt like my experience was disparaged or put down, but I was too young to really understand that.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Miko Charbonneau’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

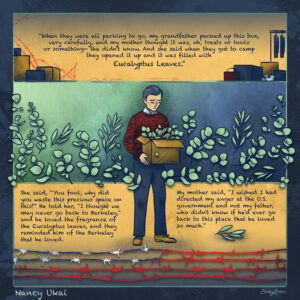

EUCALYPTUS by Emily Ehlen

This image titled EUCALYPTUS consists of three panels. The top panel depicts suitcases and boxes of various sizes, and includes text which reads, “When they were all packing to go, my grandfather packed up this box, very carefully, and my mother thought it was, oh, treats or tools, or something—she didn’t know. And she said when they got to camp and opened it up and it was filled with Eucalyptus Leaves.” The words “eucalyptus leaves” are larger than the other words. In the center, the grandfather stands in front of all of the panels with a box of eucalyptus leaves. He is looking down with a sad expression. The bottom panel depicts some eucalyptus leaves as well as barbed wire that mimics the red, white, and blue of an American flag. This panel includes text which reads, “She said, ‘You fool, why did you waste this precious space on this?’ He told her, ‘I thought we may never go back to Berkeley,’ and he loved the fragrance of the Eucalyptus leaves, and they reminded him of the Berkeley he loved. My mother said, ‘I wished I had directed my anger at the U.S. government and not my father, who didn’t know if he’d ever go back to this place that he loved so much.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Nancy Ukai’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

SPLASH by Emily Ehlen

This image titled SPLASH consists of two panels on the top and two on the bottom. The top left panel depicts a younger woman and an older woman in a boat. Text above the top two panels reads, “The U.S. Government told my mother, ‘It is advisable that you move as far away from California as you can. Stay away from other Japanese. Try to become even more American than you think you are, than you already are.'” The top right panel depicts the two women holding hands and standing in the boat. The text below these panels reads,”‘Just quietly go about your business even though this horribly unconstitutional thing has just happened to you and you’ve suffered all this trauma. But try to be American. Try to fit in.'” The bottom left panel depicts a close-up of the women holding hands above the boat and a ripple in the water. Beneath the hands, the text reads, “We were told, ‘Don’t rock the boat, do not make waves.” Beneath the boat, the text reads, “Nonsense. Let’s go make a Big Splash!” The bottom right panel depicts the two women holding hands and jumping into a sea of waves. Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jean Hibino’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

TOPAZ by Emily Ehlen

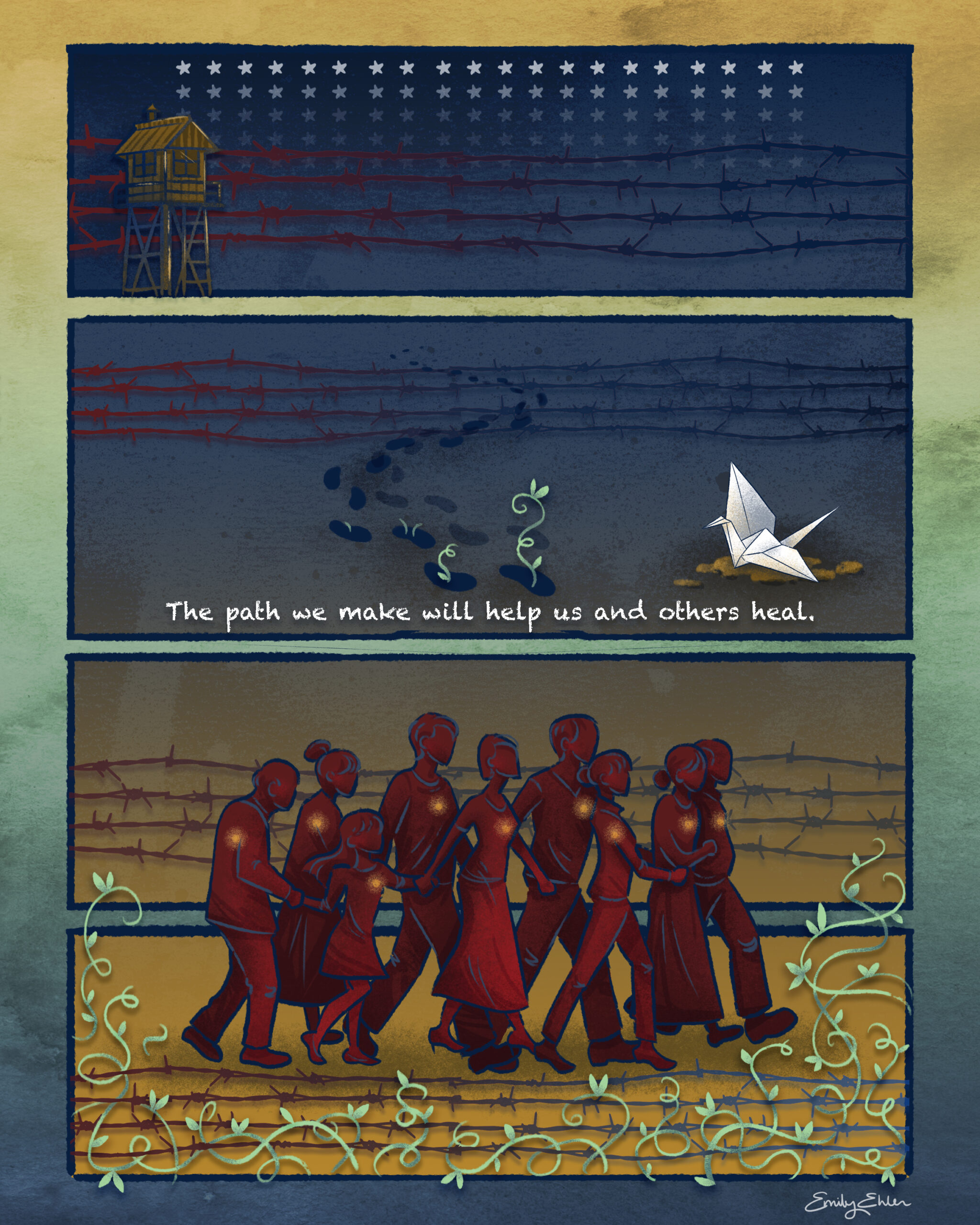

This image titled TOPAZ consists of four panels. The top panel depicts white stars behind barbed wire in red and blue that mimics the American flag, as well as a guard tower. The next panel depicts footsteps with plants sprouting from the final four steps. To the right of the footsteps, a white paper crane rests on soil. Red and blue barbed wire appears in the background. Text at the bottom of this panel reads, “The path we make will help us and others heal.” The bottom two panels depict barbed wire at the top and bottom, which frame a group of people all holding hands walking to the right. The group of people, which includes a range of ages, spans both panels. The individuals have glowing lights over their hearts. Plants sprout from the bottom of this panel.

SILENCES by Emily Ehlen

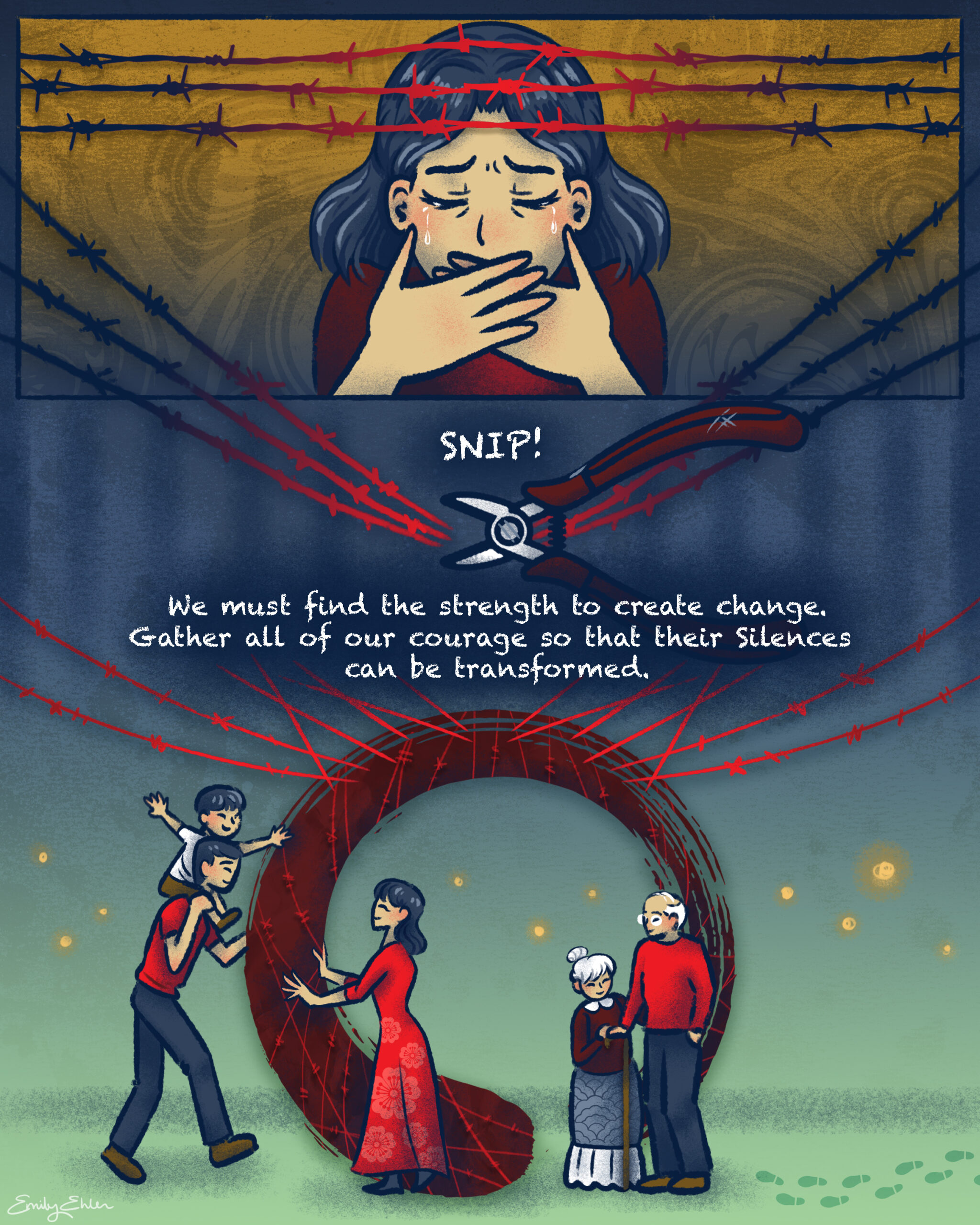

This image titled SILENCES consists of two panels. In the top panel, a woman cries while framed by red barbed wire. The bottom panel depicts wire cutters snipping the red barbed wire. Text reads, “SNIP!” Beneath the barbed wire is text that reads, “We must find the strength to create change. Gather all of our courage so that their silences can be transformed.” Beneath this text is a scene depicting a man with a child on his shoulders moving toward a woman with open arms. To the right of them are an elderly woman and man. Behind the group of people, there is a large, red circular ensō formed from the barbed wire. Glowing lights also appear in the background.

TREE by Emily Ehlen

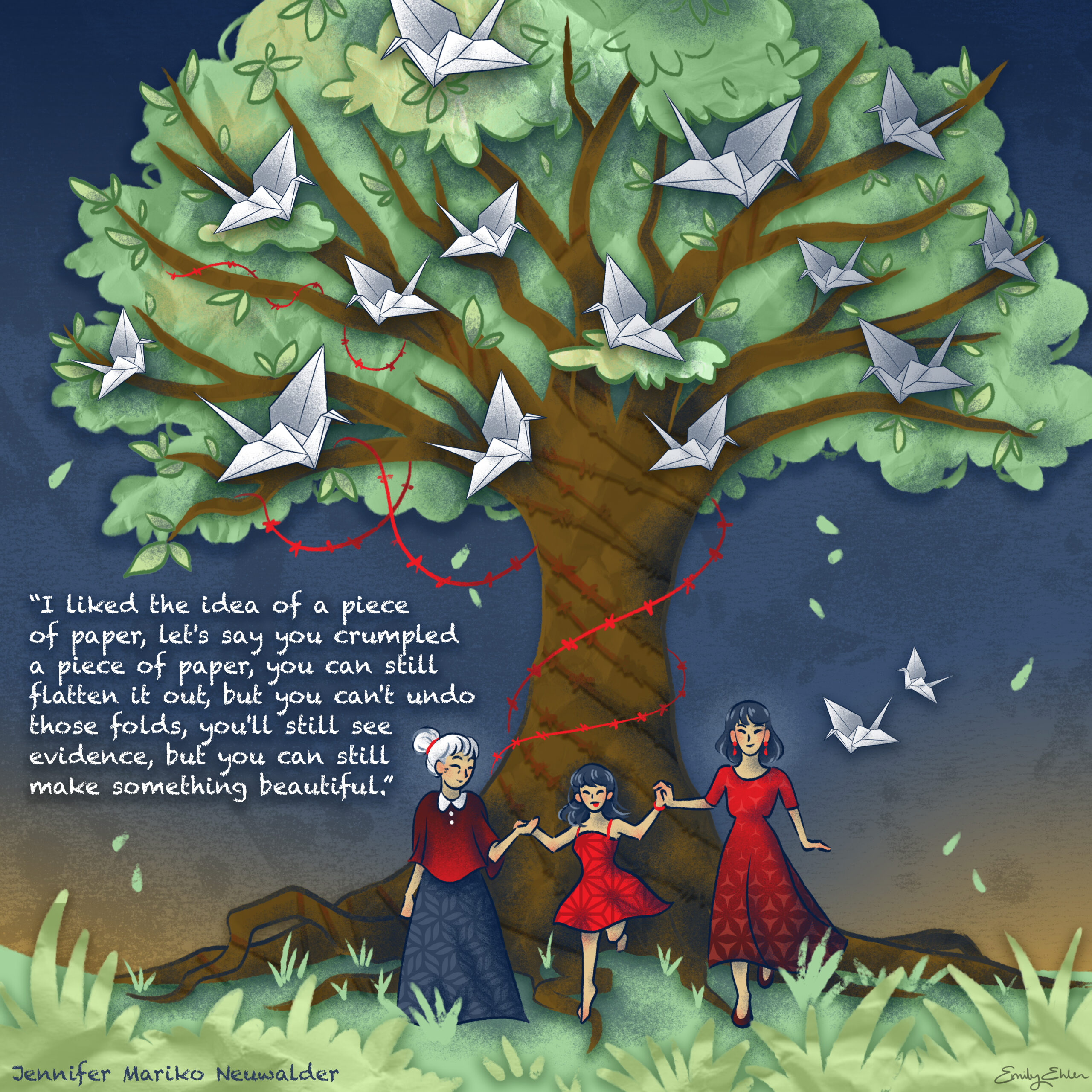

This image titled TREE consists of one panel, depicting three women of different generations holding hands in front of a large tree wrapped in red barbed wire and filled with white paper cranes. This image includes text which reads, “‘I liked the idea of a piece of paper, let’s say you crumpled a piece of paper, you can still flatten it out, but you can’t undo those folds, you’ll still see evidence, but you can still make something beautiful.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

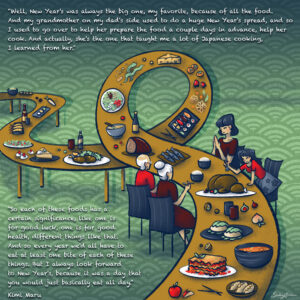

FEAST by Emily Ehlen

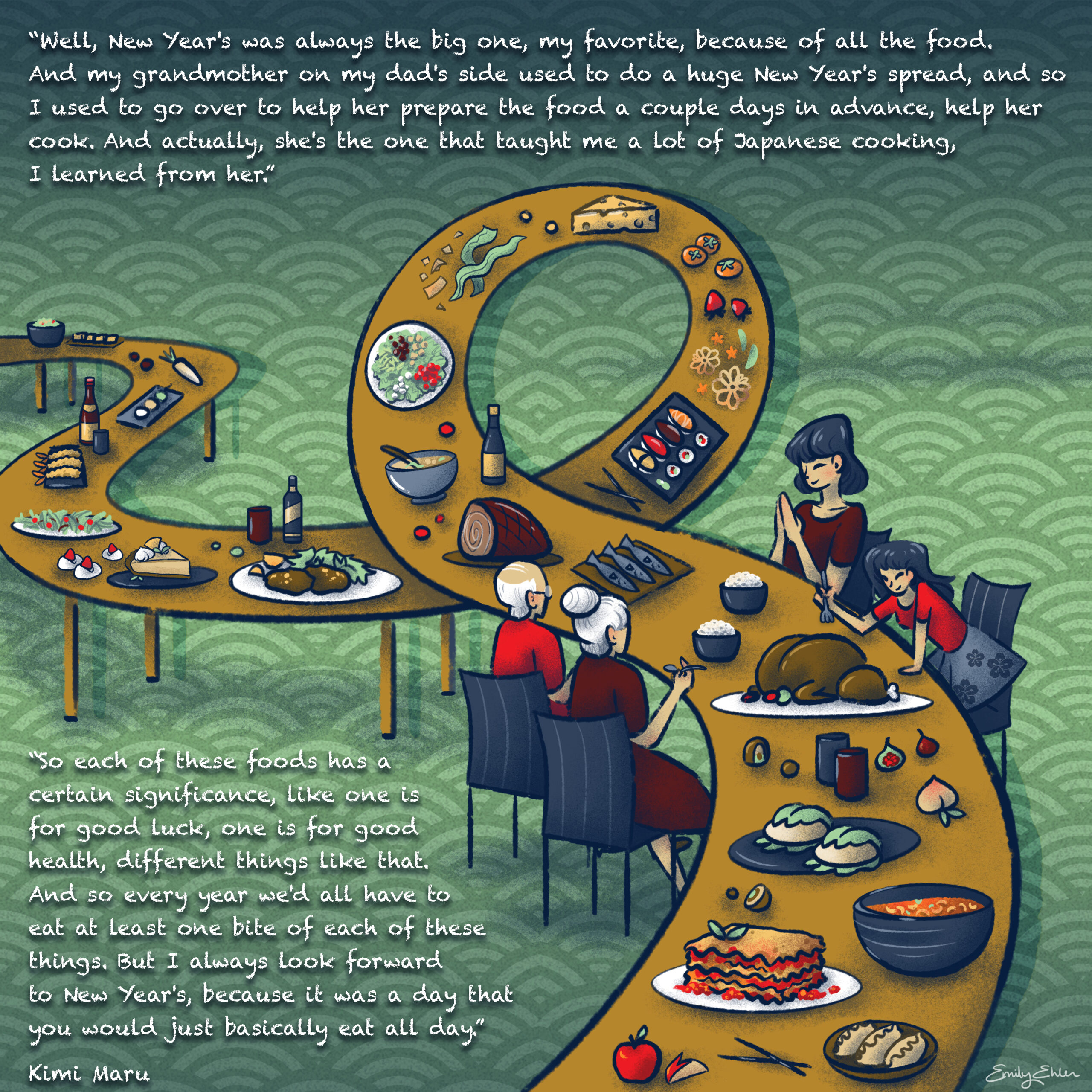

This image titled FEAST consists of one panel that depicts a long table that stretches from the left side to the bottom right which loops before reaching four people of different generations eating. The food on the table includes a variety of foods like sushi, lasagna, salad, turkey, and dumplings. Text at the top of the image reads, “‘Well, New Year’s was always the big one, my favorite, because of all the food. And my grandmother on my dad’s side used to do a huge New Year’s spread, and so I used to go over to help her prepare the food a couple days in advance, help her cook. And actually, she’s the one that taught me a lot of Japanese cooking, I learned from her.'” Text on the bottom left of the image reads,, “‘So each of these foods has a certain significance, like one is for good luck, one is for good health, different things like that. And so every year we’d all have to eat at least one bite of each of these things. But I always look forward to New Year’s, because it was a day that you would just basically eat all day.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Kimi Maru’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

Explore the oral history interviews in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, listen to The Berkeley Remix podcast season “’From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” and discover related resources on the Oral History Center website.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Q&A with Artist Emily Ehlen on Illustrating the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

For the first time, the Oral History Center, or OHC, partnered with an artist named Emily Ehlen, who created ten graphic narrative illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project. The JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

Below is an interview with Emily Ehlen about her processes in creating such dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators. You can see and save copies of larger images of Emily’s artwork for the JAIN project in a separate blog post.

Artist Bio:

Emily Ehlen is best known for her colorful and whimsical illustrations using mixed media. Watercolor, ink, spray paint, and gouache are the primary mediums she uses for her traditional works, and she also integrates them in her digital pieces. She loves being positive and expressing her interests while using her surroundings as inspiration. To invoke curiosity and imagination, her drawings reflect an open view of the subject and are framed with pieces of expression and reality. Change and adaptability are a constant as she goes through various experimentations and approaches to her art.

Q&A with artist Emily Ehlen:

Q: What was your process for creating the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives artwork?

Emily Ehlen: My process started with selecting powerful imagery and phrases in relation to connecting themes found throughout the oral history transcripts. I composed thumbnails with the intent to represent the information clearly and use symbolism to convey the narrative. I wanted to use as much text from the source as I could, but I wanted to avoid it being too word heavy. It was a balancing act of editing the text and imagery to support each other in the composition and narrative. After developing and consolidating the initial drafts I moved on to tighter linework and color concepts. Once the colors were established, I inlaid patterns and handmade textures to add contrast between objects, panels, and the background. The handmade textures were made with ink washes and spray paint. The final step was applying shading and details to enhance the focus of each element while also keeping the flow throughout the entire composition.

Q: How was your work on this project similar or different to your prior art projects?

Emily Ehlen: This Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives art project was similar to the comic series Drawn to Art: Tales of Inspiring Women Artists that I worked on in 2021 for the Smithsonian American Art Museum. For that Smithsonian project, I drew a three page comic called “Weaver’s Weaver,” featuring Kay Sekimachi, a Japanese American artist. My process for both projects were pretty identical. Although, I think I had a little more freedom with expanding the storytelling elements working on the JAIN project comics. Overall, they were mutually great experiences that I am so grateful to have been a part of.

Q: How did engaging with the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives oral history transcripts shape the stories you chose to tell and some of the imagery you used in your graphic art?

Emily Ehlen: When drafting the concepts of the illustrations, I wanted to use imagery that would convey the message the stories presented. Reading the oral history transcripts, I found lots of interesting details to include, like with the different types of food to include in the FEAST composition. It was inspiring to hear everyone’s unique voice sharing aspects about their and their family’s lives.

Q: How did you choose the various scenes and stories that you eventually depicted? What stories in the transcripts most stood out to you? Why?

Emily Ehlen: I illustrate with the goal to portray a story the audience can connect and respond to. I wanted to choose stories with lots of emotions that I could highlight in each drawing. The piece I got the most emotional while drawing was Nancy Ukai’s grandfather in EUCALYPTUS. I sympathized with the longing and sadness of missing Berkeley that her grandfather felt. I understood the rationality behind using the box for something else, but that emphasized just how important Berkeley was to him. It was heartbreaking to read, so I knew I had to draw it.

Q: What are some of the story themes that you worked to express throughout your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: The focus was how the Japanese American incarceration during World War II impacted themselves, their families, and how they responded to it. The themes were identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. I wanted the weight of the words to be carried through to the art accompanied with them.

Q: Can you describe some of the visual themes or repeated imagery that you incorporated throughout the various pieces you created? How and why did you develop these visual themes?

Emily Ehlen: The color palette I used helped create the tone and atmosphere of each piece separately while also keeping the collection cohesive. The red was used with duality: the bright saturated hue represented youth, rebelliousness, and intensity; while the dark maroon represented authority and repressed quietness. The soft green color was used to depict change and positivity that connects to the healing theme. The navy blue signifies unity and freedom, but it is used with a sense of serenity and heaviness. For example, the blue in TEACHER extrudes an overbearing presence in contrast to when it’s used in TREE. The ochre yellow has different meanings for its surroundings, like in TEACHER it signifies uncertainty, and in STORIES it’s used to display hope.

The water pattern, waves, and watercolor texture are used with family elements, and it contrasts the dry gritty spray paint texture that references the environment of Topaz and Manzanar. Waves are symbols of growth, renewal, and transformation. They also represent the unpredictability of life, to which people learn to navigate its ups and downs. The plants and paper cranes also relate to family connections, development, and healing, going through many stages and flourishing together.

For darker imagery, I wanted the red barbed wire to be synonymous with the red stripes we see on the American flag. To show the lack of freedom and injustice that the Japanese Americans faced, those stripes became wire that entrapped and left scars on following generations. The guard towers were a beacon of looming authority and danger at the incarceration camps. They became a mental block for some that were confined in their silences.

Q: While creating the JAIN art, what did you learn that was new to you?

Emily Ehlen: I really enjoyed learning about everyone’s perspectives and experiences with being Japanese American. I am Chinese American, so I empathize with the stories about identity and the sense of belonging. This project lit up my desire to discover more about my culture. My motivation for drawing is to see how my art mirrors my development as a person. I think art is a record of growth and change. Like time, it never stops moving forward.

Q: Can you describe one or two of your favorite pieces that you created for this project? Why does this one stand out for you?

Emily Ehlen: This is like asking the question, “Who’s your favorite child?” It’s super difficult because I love each piece for different reasons. I had the most fun drawing the piece SPLASH, about Jean Hibino and her mother. I think it has the most dynamic composition with how the imagery flows together with the text. I like the sequence of stillness to movement, and how a ripple can start a wave.

Q: What are your hopes for how people engage with your art for this project? Who do you hope sees it? What do you hope people take away from your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: My hope for how people engage with the comic is to have open conversations about them or topics related to it. It would be nice to see what sticks out to people the most and what connections they make through their perspectives. I hope people are able to feel the sentiments in each piece and learn new aspects of its history. I can’t think of anyone specific I’d want to see it, but I strive to be someone who inspires others by taking creative approaches to new ideas. So, I hope other artists who are interested in drawing and story-telling see it

You can see and save copies of larger images of the graphic art that Emily Ehlen created for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project in a separate blog post. We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.