Digital Humanities

Podcast episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit” in The Bancroft Gallery exhibit VOICES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT: A CENTURY OF BAY AREA ACTIVISM

Listen to podcast episode 1, “A Preservationist Spirit,” or read a written version of this podcast episode below.

Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism is a gallery exhibition in The Bancroft Library that charts the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area through the voices of activists who advanced their causes throughout the twentieth century—from wilderness preservation, to economic regulation, to environmental justice. The exhibition is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library. Curated by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, this interactive exhibit is the first in-depth effort to showcase oral history along with other archival collections of The Bancroft Library.

This exhibition includes three podcast episodes that offer deeper narratives to supplement the archival posters, pamphlets, postcards, photographs, oral history recordings, and film footage that are also presented in the gallery. Please use headphones when listening to podcasts in The Bancroft Library Gallery.

A written version of podcast episode 1 is included below.

Listen to episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit” on SoundCloud.

PODCAST EPISODE SHOW NOTES:

Episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit.” This podcast episode accompanies a section of the Voices for the Environment exhibition that explores how, after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, demands to rebuild San Francisco targeted the state’s ancient and fire-resistant redwood trees, while desires for a reliable water supply called for damming the Hetch Hetchy Valley within Yosemite National Park. In the decades that followed, an outpouring of activism shaped the ensuing conflict between economic development and environmental protection, and fueled a preservationist spirit in the Bay Area that would only grow over the century.

This podcast episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities” collection recorded in the late 1970s by Frederick M. Wirt, as well as oral history interviews with Carolyn Merchant recorded in 2022, with Ansel Adams recorded in the mid-1970s, and with David Brower recorded in the mid-1970s. The oral history of William E. Colby from 1953 was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar from 1958 was voiced by Ross Bradford. This episode also features audio from the film Two Yosemites, directed and narrated by David Brower in 1955. This episode was narrated by Sasha Khokha of KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine.

This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, with help from Sasha Khokha of KQED. The album and episode images were designed by Gordon Chun.

WRITTEN VERSION OF PODCAST EPISODE 1: “A Preservationist Spirit”

Anonymous Witness 1: The older people were running around wild! They thought it was the end of the world. Everything was shaking.

Anonymous Witness 2: Kind of a low roar. You had the feeling that the roof was coming off.

Anonymous Witness 3: It was a six-story brick building. We were on the third floor. When we finally got out of the building, we were on the top floor. The top three had gone off.

Anonymous Witness 2: By night the city was—it looked like the whole downtown area was on fire

Anonymous Witness 1: Everything was burned, you couldn’t—the home was gone. Everything was gone.

Sasha Khokha: Those are voices of people who survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. And they’re just some of the rare recordings you’re going to hear in Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism.

[music]

This podcast accompanies an exhibition in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley that’s the first major effort to bring together both the oral history and archival collections of The Bancroft Library. You’re about to hear more voices recorded by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, founded in 1953 to record and preserve the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century, and highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—starting with efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. We’ll also learn about the midcentury fight for state environmental protections, and demands to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color across the Bay.

You’re listening to the first episode of Voices for the Environment. We’re calling it “A Preservationist Spirit.” I’m your host, Sasha Khokha, from KQED.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: A beautiful vista, an ancient forest, a flooded valley. Our relationships with the world around us define who we are, from the air and water that sustains us, to the natural spaces we enjoy, to the creatures we share our surroundings with. Together, we refer to these intertwined elements as “the environment.” Sometimes we struggle with how to change those relationships. We call that work “environmentalism.”

[piano music from the early twentieth century]

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a new environmental spirit was flourishing in the first decade of the twentieth century. The catalyst for this public activism was not pollution, oil spills, or climate change. Not yet. Back then, it was the 1906 earthquake and fire.

On the morning of April 18, 1906, a massive earthquake struck just two miles off the coast of San Francisco, then California’s largest city. The quake, with an estimated magnitude of 7.9, was absolutely devastating. Thousands of buildings crumbled to the streets, reducing vast sections of the city to rubble. The recordings you’re about to hear are rare, firsthand accounts of people from the Bay Area who survived the harrowing event. These interviewees were children back in 1906, and they recounted their experiences decades later.

Anonymous Witness 5: I was ten years old, I’d just had a tenth birthday, but I had never heard of an earthquake, I didn’t know the word.

Anonymous Witness 6: We woke up. It’d shake, shake you right out of bed, but we couldn’t get out. The house boxed and the doors jammed, and we had a heck of a time.

Anonymous Witness 5: My mother got us into the doorway and stood us there. And she said, “now stand right here.” And she stood us right in the doorway, “Stand right here.” I said, “Well, what is it?” And we could look across the room and out the building and see the buildings collapsing out there.

Anonymous Witness 1: But when the earthquake came in 1906, the day of it, my mother had a baby girl on that morning. She was ill all evening, all night. The earthquake was so strong that, we lived on the first floor, and on the third floor, the balcony and everything fell down. And fire, our kitchen caught fire, there was my father. So finally, the people—there was a little Irish lady who lived next door with her two young sons, I think they were seventeen and nineteen at that time. Her sons broke the windows and took mother, the mattress, baby and all, brought them outside on the sidewalk. I remember that like yesterday.

Anonymous Witness 3: We were four people living in one large room in what was called the Old Supreme Court Building, which was diagonally situated across or located across from the City Hall. Larkin and McAllister Streets. It was a six-story brick building. We were on the third floor. When we finally got out of the building, we were on the top of it. The top three had gone off.

Anonymous Witness 2: So my father said, “You’ve got to get up. You’ve got to get up and dress.” First thing, we went out in the street and you could smell gas. People were all out of their homes in their pajamas and their nightshirts, and so forth, wanted to see what’s happening. Well, it wasn’t too later in the morning when we fully dressed and went out and down the street. And the street car on Geary [Street], the rails were all up in the air and bent. Big gaps, you didn’t, couldn’t—you wondered how far down it went, big gaping holes.

Anonymous Witness 5: And we watched people go by with empty bird cages, and wheeling empty baby buggies, and you know, in a state of complete shock.

[sound effect: fire bell ringing]

Sasha Khokha: As devastating as the earthquake was for San Francisco, it was fire that caused most of the damage. The quake ruptured gas main all throughout the city, sparking nearly three dozen fires, producing an inferno that burned for three-days straight. To make matters worse, firefighters and residents in San Francisco soon ran out of water.

Anonymous Witness 2: And then, about Noon time, we got word that city’s on fire and there’s no water

Anonymous Witness 1: We didn’t have a stitch of clothes on, just an up-top shirt, couldn’t get anything. He went back, thinking he’d be able to save something. Everything was burned, you couldn’t—the home was gone. Everything was gone, so we didn’t.

Anonymous Witness 5: We had gotten some blankets from my aunt. And of course, we went out with nothing from our building except what we were wearing. And we got some blankets from my aunt, and we slept in that—we stayed in that lot. That’s my first recollection of the fire, because from there we could watch everything burn.

[sound effect: dynamite demolition explosions]

Sasha Khokha: No water and a raging fire left city officials only one option: to create fire blocks by dynamiting the buildings that stood in the fire’s path so there would be nothing left to burn.

Anonymous Witness 5: We watched them blast down on Valencia Street and down on Mission Street, sort of backfiring, watched them blast the old theater out there, the Valencia Theater. We slept under the blankets that night, and had to wake every once in a while and shake them because they were heavy with ashes.

Anonymous Witness 4: I recall going to where the Mint is today to watch the fire from where the Mint is on that hill. We could see the fire burning downtown from there on Baker.

Anonymous Witness 2: There’s the school up—it’s right up the hill here—the Lone Mountain College. It was a bare hill at that time, that’s where the name Lone Mountain came to be. So, we walked up there, and by night the city was—it looked like the whole downtown area was on fire.

Anonymous Witness 6: Mr Shields had an automobile, he was the third neighbor to us. So we went down on Market Street. Here was the Palace Hotel, and we were here. And we saw the windows go boom-boom from the heat.

Sasha Khokha: Here’s more recollections of what became known as the Great Fire of 1906.

Anonymous Witness 7: We could see the flames, the fire, from the hills that were burning, all the houses. And the Fairmont Hotel was being built at the time, and it wasn’t finished. And the fire was all around there, but I don’t think it did that much damage there. But just like it was over the sky above us.

Anonymous Witness 2: I can recall the first night when the city was on fire, saying nothing, just staring there next to my father. And I cried and cried. He finally looked down at me and he says, “Well, what can you do about it?” I said, “There goes San Francisco.”

Sasha Khokha: When the last fire was finally extinguished, San Francisco lay in ruins. The earthquake and fire had claimed over 3,000 lives and destroyed 80 percent of what was then the largest and richest city west of Chicago. Within weeks, the mission to rebuild San Francisco got underway.

What you may not know is that the plan to rebuild involved cutting down some of California’s ancient redwood forests. Coastal redwood trees (known scientifically as Sequoia sempervirens) are among the largest and oldest organisms living on Earth. They’ve survived along California’s coast for at least 20 million years, some of them reaching more than 300 feet high and twenty feet wide. That giant size made them a prime timber source to rebuild the devastated city, especially because redwood is pretty fire resistant.

That started a logging frenzy. Timber interests like the Redwood Car Shippers Bureau circulated promotional photos showing buildings constructed out of redwood still standing amid a burned-out San Francisco skyline. [sound effect: sawing wood] In the years that followed, lumber mills up and down the coast worked overtime to meet the city’s endless demand. And record shipments of redwood made their way to San Francisco Bay.

And here’s where the earthquake and fire led to an early call for environmental preservation. Bay Area residents, including John Muir and other members of the newly formed Sierra Club, spearheaded the effort to stop logging redwoods. Muir was an immigrant from Scotland who fell in love with the Sierra Nevada. In the late 1800s, he settled in the Bay Area city of Martinez. In 1892, he and other Bay Area residents founded the Sierra Club with an early mission to explore, preserve, and protect California’s mountains and forests. They feared the logging frenzy to rebuild San Francisco had already taken its toll on the region’s redwoods.

Take the area around Palo Alto. Located 30 miles south on the peninsula, the city got its name from surrounding redwood forests. Palo Alto means “tall tree” in Spanish. In the years after the earthquake and fire, that reference would be lost though, because rebuilding San Francisco depleted those “tall tree” forests.

Concerned residents throughout the Bay Area reacted quickly. They started lobbying the state and federal government to protect the region’s remaining redwood groves. State officials responded by expanding the boundaries of Big Basin Redwoods State Park in the Santa Cruz mountains. It’s California’s first and oldest state park, founded in 1902. Over the decades, the protected area of Big Basin would steadily expand to include some 18,000 acres. That’s 6 times as big as the park’s original boundaries.

Federal officials took action to preserve the redwoods, too. In 1908, Bay Area Congressman William Kent led the charge to federally protect 295 acres of redwood forest in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. The preserved area is known as Muir Woods National Monument. Here’s what John Muir wrote to Kent shortly after the Monument’s creation: “Saving these redwoods from the axe and saw, from money-changers and water-changers, and giving them to our country and the world is in many ways the most notable service to God and man I’ve heard of since my forest wandering began.”

John Muir and other men became figureheads of environmental preservation. But women played a critical—yet often overlooked—role in early environmental activism, too. Women provided much of the grassroots momentum to save California’s redwoods through letter writing, lobbying, fundraising, and leading various organizations. Women in the Sempervirens Club and California Club were instrumental to the creation of protected areas like Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Muir Woods National Monument, and Calaveras Big Trees State Park. The creation of these protected areas forced timber companies to concentrate their operations in more remote regions along the North and Central coasts. But the activists in women’s organizations, from the California Federation of Women’s Clubs to the Women’s Save the Redwoods League, kept pushing to protect those regions, too.

Men may have cast the votes in congress and state government to protect redwood forests, but it was the activism of women throughout California that helped put these issues on the table in the first place. Here’s UC Berkeley environmental historian Carolyn Merchant:

Carolyn Merchant: Women had power, but they had power through their roles in a traditional patriarchal society, so that they could do more things within that patriarchy than had been thought of before. And so women began to feel a sense of power, a sense of what they could do. And they can actually assert that power in order to help save the planet, and how women themselves can become important forces in the whole role of conservation and resources.

Sasha Khokha: The tug-of-war between the development of cities like San Francisco and preservation of California’s redwood forests—that was a fight that would continue for decades, putting the focus on humans, rather than fire or pests, as the primary threat to these ancient trees and their environments. This battle helped ignite and expand the preservationist spirit that would shape environmental activism in the Bay Area for the next century.

[music]

San Francisco had long impacted environments well beyond its city boundaries. In the wake of the 1906 earthquake and fire, the city’s efforts to rebuild began to affect more remote regions of the state, including areas previously protected by preservationists. And as rebuilding San Francisco continued, the city began to need not just trees, but water.

In 1908, city leaders proposed a project to provide a reliable water source for San Franciscans. The scale of the idea was unprecedented. They wanted to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley, which was then preserved as part of Yosemite National Park. The plan was to engineer a system to carry the water 160 miles to San Francisco—what used to be a 2 day stagecoach ride before the Yosemite Valley Railroad opened in 1907.

The proposal to dam Hetch Hetchy sparked a five year debate, from San Francisco city hall to the steps of congress in Washington DC. The preservationists who opposed the dam were led by John Muir and other Sierra Club officials. They argued Hetch Hetchy Valley was a sacred piece of Yosemite National Park. If it were sacrificed to bring water to San Francisco, that would set a dangerous precedent for tapping into resources in all kinds of protected areas.

William E. Colby: Another outstanding matter that came before the Sierra Club for action, and John Muir was strongly behind it, was what we refer to as the Hetch Hetchy fight. The Hetch Hetchy Valley had been included in Yosemite National Park largely as a result of John Muir’s efforts.

Sasha Khokha: That was Anders Hauge [How-gee] reading the oral history of William E. Colby, who stood on the frontlines with John Muir during the Hetch Hetchy campaign. Colby, who was born and raised in the Bay Area, held the post of Secretary of the Sierra Club for more than forty years. He led campaigns to expand Sequoia National Park, as well as create Olympic and Kings Canyon National Parks. Here is Hauge again reading from Colby’s 1953 oral history about how he cut his political teeth in the fight to keep Hetch Hetchy preserved.

William E. Colby: San Francisco became interested in acquiring this as a municipal water supply. When we heard of it, of course John Muir was tremendously exercised to think that a great part of his work would be undone. And so the Sierra Club very strongly opposed this application by the city of San Francisco. We were successful in preventing the grant for a number of years.

Sasha Khokha: But city developers pushed back. Creating a viable water supply? That was progress. It would help bring fresh water to a thirsty city. Developers also drew heavily on the imagery of a vulnerable San Francisco left without water in the face of a raging fire. The 1906 earthquake and fire was the first natural disaster captured on film. So advocates for the dam had lots of material to help make their case.

William E. Colby: But the tide turned when Woodrow Wilson became president, because he named Franklin K. Lane, who had been City Attorney of San Francisco when the application for the Hetch Hetchy site had been made, Secretary of the Interior. Because of this change in the political situation, we found that we were at a great disadvantage. We had tremendous support from many sources. But this political change was too powerful for us. We even enlisted the support of civil engineers, hydraulic engineers, who aided us in preparing reports showing that there were half a dozen other sources of supply that San Francisco could have obtained. And that was absolutely demonstrated later on by the fact that Oakland went over to the Mokelumne River and obtained a very fine water supply and brought it into Oakland long before San Francisco got the Hetch Hetchy supply. We were handicapped in every direction.

Sasha Khokha: In the end, Congress sided with the city of San Francisco, passing the 1913 Raker Act, which permitted the flooding of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite. And the construction of the massive O’Shaughnessy Dam, with an extensive water-delivery system. Colby recalled in his 1953 oral history how this decision impacted his friend and mentor, John Muir.

William E. Colby: The loss of Hetch Hetchy Valley was a tremendous blow to John Muir. I’m quite sure that this loss of the Hetch Hetchy Valley had a great deal to do with Mr. Muir’s subsequent Illness and ultimate death. He probably died in advance of the time that he would have if the attempt to save Hetch Hetchy had not gone against him. Muir didn’t mince any words in expressing his ideas of the tremendous loss to the nation by reason of the flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Sasha Khokha: John Muir died in December of 1914 – one year after congress voted to authorize San Francisco’s plan to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley.

[piano music]

Decades later, native San Franciscan and famed photographer Ansel Adams shared his grief over the loss of Hetch Hetchy. Adams joined the Sierra Club shortly after Muir’s death and would build his career photographing Yosemite National Park.

Ansel Adams: We lost the Hetch Hetchy. And one of the great disappointments there was Gifford Pinchot’s support of it. You see, he really turned the trick with the secretary of the interior.

Sasha Khokha: Gifford Pinchot as America’s first professionally trained forester. From 1898 through 1910, he served three American presidents in the US Department of Agriculture as the nation’s chief of forestry. He also became a major supporter of damming the Hetch Hetchy Valley. If John Muir became a figurehead for the preservation of nature, Pinchot’s early leadership of the US Forest Service symbolized the corporate and multi-use model of natural resources.

Ansel Adams: People forget the Forest Service is primarily a commercially oriented, really, a controlling administration. It’s just recently that they’ve been stressing “many uses” for political reasons. It sounds very fine, and in many ways is all right. But when you get into very beautiful areas that should have park or wilderness status, see, it doesn’t work.

Sasha Khokha: As Adams recalls, the Hetch Hetchy site was not just about getting water, but hydroelectricity for the growing city of San Francisco. That would help build the power grid of the utility giant Pacific Gas and Electric, or PG&E.

Ansel Adams: The Hetch Hetchy—where are you going to get your water? In San Francisco, that’s our water supply. And San Francisco, that is a big community. And the Russian River was considered. See, what happened there was that there was another site further down that would be much bigger in expanse but not so deep. And we worked for that very hard, but that could not provide enough power. There wouldn’t be enough “fall.” But the whole Hetch Hetchy was put where it is, in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, because of the favorable power situation.

Sasha Khokha: Some of the defenders of Hetch Hetchy came from San Francisco’s business community, like Francis Farquhar [Far-kwar]. He was a Harvard-educated accountant who joined the Sierra Club a year after moving to San Francisco in 1910. He would serve more than 25 years on the Club’s board of directors, including two terms as Sierra Club president. Here is Ross Bradford reading from Farquhar’s 1958 oral history.

Francis Farquhar: I never participated in the Hetch Hetchy matter. I was in Boston at the time the bill finally passed. I had seen it in 1911 when I came out to the Sierra Club outing with Jim Rennie. We came all the way down the Tuolumne canyon and camped in the Hetch Hetchy Valley a day or two. I recognized its beauty.

Sasha Khokha: For Farquhar, the devastating loss of Hetch Hetchy had a silver lining. Because – although tragic – it may have provided one of the most powerful and lasting influences for what would become the environmental movement in the U.S.

Francis Farquhar: I think that it is too bad that the national park idea had not developed further at the time to prevent the surrender of such an important portion of a national park. Possibly, the fact that Hetch Hetchy was surrendered strengthened the whole national park idea with the slogan, “Never another Hetch Hetchy.”

[music crescendo]

Sasha Khokha: Few activists in America likely used that slogan as effectively as David Brower. Many consider him the godfather of the modern environmental movement. He’s from Berkeley, and served as the first executive director of the Sierra Club from 1952 to 1969. He oversaw a tenfold expansion of the Club’s membership and led campaigns to establish ten new national parks. Brower also pioneered the use of film, books, and other media to advocate for environmental causes. One of those was the fight against a proposed dam on the Colorado River in Dinosaur National Monument.

David Brower: I didn’t go to Dinosaur until 1953. That was the year the Sierra Club started to run river trips that were patterned after a river trip that Harold Bradley had taken his family on the year before. He went there to make a film, and made a family film, and showed around. That was certainly one of the things that awakened my interest in what was there.

Sasha Khokha: When the dam proposal came to congress, Brower and other environmentalists waged an all-out campaign to preserve Dinosaur National Monument.

David Brower: It did—at least it was important to the Sierra Club. It was important to a lot of the conservation organizations, where they could really take on the establishment and stop it. There were all kinds of—that is, whatever led Newton Drury to say, “Dinosaur is a dead duck,” was a force that was reversed, and it was reversed with a battle that had a nationwide audience. And we persuaded a good many of the people whose voices were heard in Congress. They’re a lot of people, but you find a few of the leaders and get them to go, and you’re in fairly good shape.

Sasha Khokha: In his oral history, Brower says the similarity of the dam project in Dinosaur to Hetch Hetchy was striking. He highlighted that parallel in his advocacy film, “The Two Yosemites.”

David Brower: There was one other thing that worked pretty hard, worked well in our lobbying effort. And that was the lowest budget film on record. The one I did on Two Yosemites. The budget was, I guess, five rolls of Kodachrome film and my own time. I did the editing, and I wrote the script, and then I recorded it. We put out this film, it’s an eleven-minute film. We made six copies of it. I showed those in a good many places. And it had quite an impact. That is, what had been done to Hetch Hetchy, and all the claims that were made of how beautiful a lake it would be and how great a recreational resource. Of course, it wasn’t. It isn’t. It wasn’t necessary. And the parallel with Dinosaur was so beautiful that we worked on that constantly.

David Brower in the film Two Yosemites: The other Yosemite was only a little less beautiful than this one, and a few miles to the north: Hetch Hetchy Valley. John Muir, the Sierra Club, and other conservation groups fought hard against this destructive park invasion. San Francisco argued that, without this water, they would wither; it must have this cheap power; there were no good alternatives; and the dam would enhance the beauty of the place and make it more accessible; the greatest good for the greatest number; teeming San Francisco against the few people who had yet visited Yosemite. Not one of the city’s claims has proved valid.

Sasha Khokha: David Brower’s activism, along with efforts of other preservationists, did prove successful. In 1955, the Secretary of the Interior withdrew the proposal for the dam at Dinosaur National Monument. And that campaign was just one of many environmental efforts Brower would lead from Sierra Club headquarters in the Bay Area. By the late 1960s, Brower’s leadership would elevate the Sierra Club’s national profile, transforming it from a California-based group to one of the largest and most influential environmental organizations in North America.

[music]

We’ve heard how a new and bustling San Francisco arose from the ashes of the 1906 earthquake and fire. So did a robust and ever-growing spirit of preservation, a force that would shape environmentalism in the Bay Area, and beyond, for well over the next century. The activism that began to preserve the state’s ancient redwood forests would result in forty-nine state and federally protected redwood parks in California. And the legacy of the Hetch Hetchy fight helped inform the preservation of landscapes across the U.S.—423 federally protected areas to be exact.

Yet, in the middle of the twentieth century, environmentalism in the Bay Area once again found itself at a crossroads.The Postwar development boom forced a choice between protecting the environment and using natural resources to meet the needs of a growing population. You can hear that story in our next episode of Voices for the Environment.

You’ve been listening to “A Preservationist Spirit,” the first of three episodes in the podcast Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism. It’s part of an exhibition in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley that runs from October 2023 through November 2024. This episode featured historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities Project” recorded by Frederick M. Wirt; and oral history interviews with Ansel Adams, Carolyn Merchant, and David Brower. The oral history of William E. Colby was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar was voiced by Ross Bradford. To learn more about these interviews and the Oral History Center, visit the website listed in the show notes. This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor, with help from me, Sasha Khokha. Thanks to KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. I’m your host, Sasha Khokha. Thanks for listening!

End of Podcast Episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit.”

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including for each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 5 (julio): Los Lucidarios de Sancho IV y otros manuscritos hispánicos de interés

Mario Cossío Olavide

Universidad de Salamanca/IEMYRhd

University of Minnesota/Center for Premodern Studies

Los Lucidarios

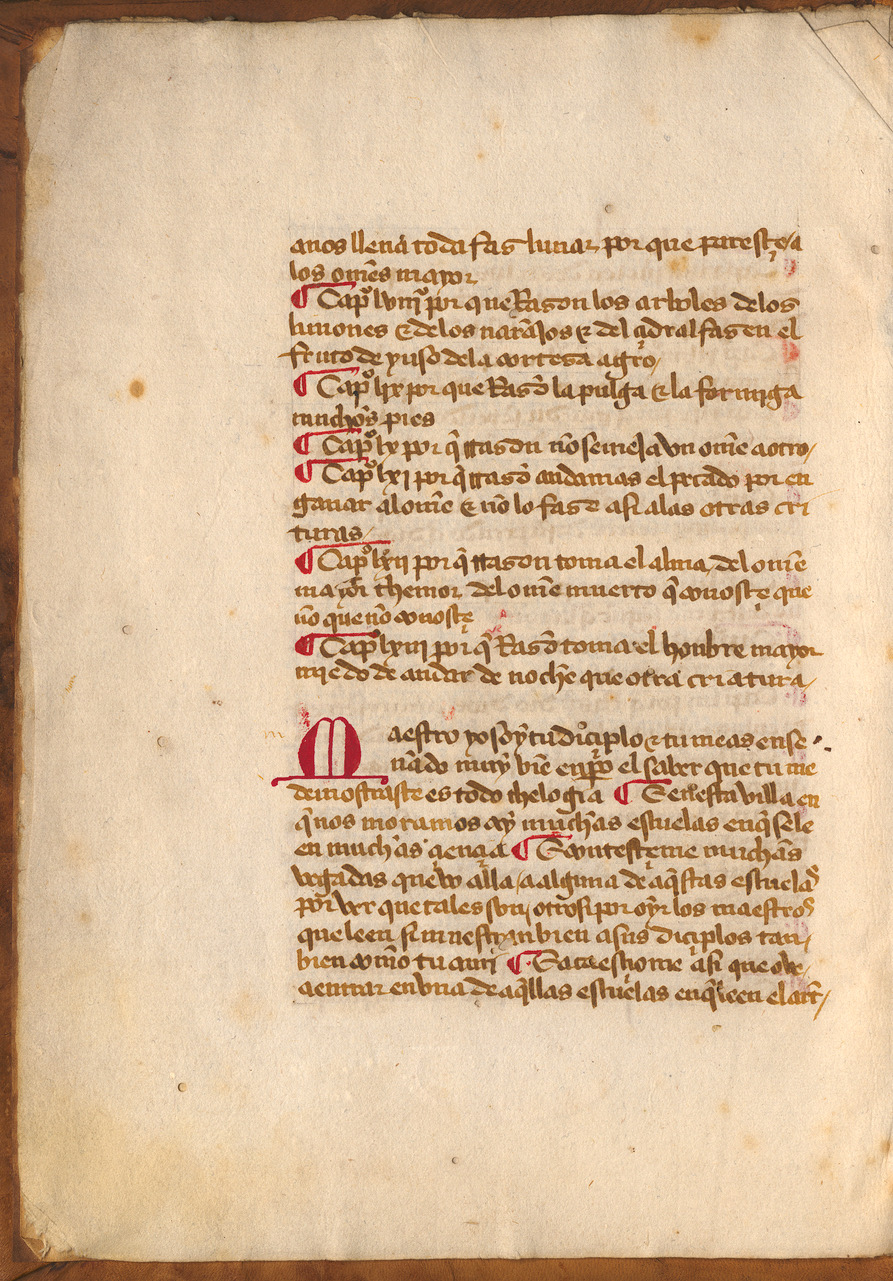

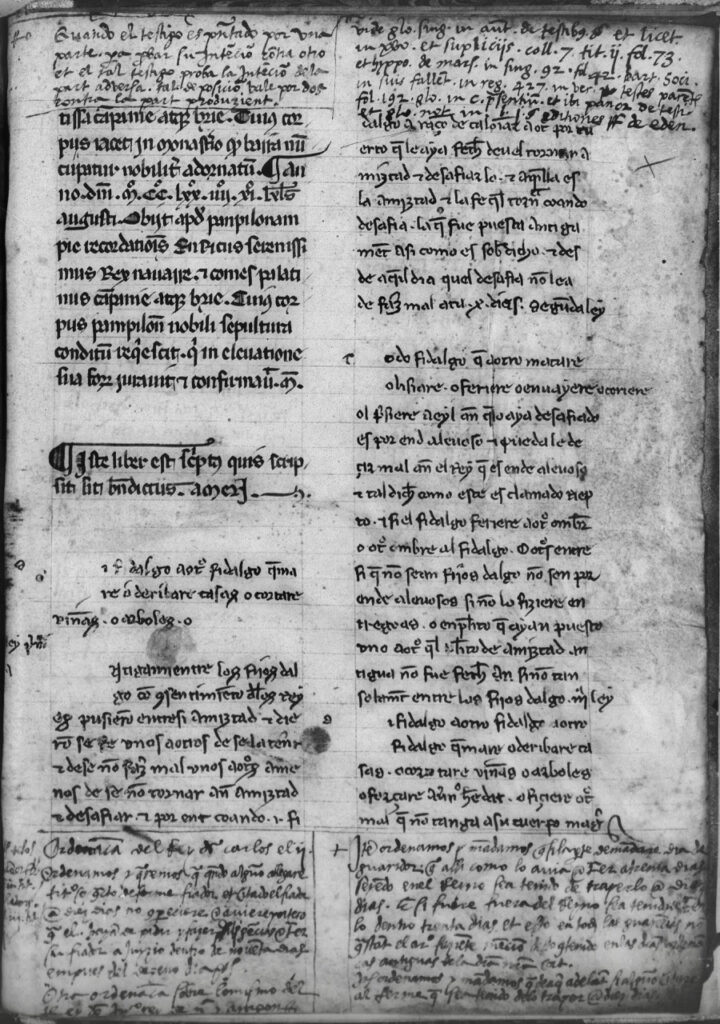

Cuando el célebre inspector de bibliotecas Henri Omont realizó el catálogo de los fondos de las bibliotecas públicas de Rouen, anotó que el manuscrito A283 de la Bibliothèque municipale –hoy Bibliothèque patrimoniale François Villon–, era un texto castellano del siglo XV al que le faltaba el título y que comenzaba en medio de la tabla de rúbricas. Tras la tabla, seguía el contenido de la obra, cuyas primeras líneas copió fielmente: “Maestro, yo soy tu discípulo e tú me as enseñado muy bien” (Catalogue générale, 184). El texto corresponde con el inicio del marco narrativo del Lucidario (BETA texid 1242).

Imagen 1. Rouen: Bibliothèque municipale, Ms A283, f. 2v

El manuscrito transmite el octavo testimonio conocido de esta obra auspiciada por Sancho IV, al que le he dado la sigla H (BETA manid 6360). Se trata de una copia posiblemente realizada en los talleres napolitanos de los reyes de Aragón y que llegó a Rouen gracias a la compra de manuscritos de Federico I de Nápoles realizada por el cardenal Georges d’Amboise durante el exilio del monarca en Tours (para una descripción completa de su contenido, véase Cossío Olavide, “Un nuevo manuscrito”).

A H hay que sumarle un noveno testimonio, I (BETA manid 3067), que identifiqué hace unas semanas. La existencia de este texto también pasó desapercibida por mucho tiempo. Se encontraba en la Biblioteca Ducal de Medinaceli y de él había dado cuenta Antonio Paz y Meliá con una enigmática nota en su parcial catálogo del fondo, entre los “manuscritos curiosos”: “Libro del rey Sancho IV – Diálogo entre maestro y discípulo (Letra del siglo XV)” (Serie 2: 537). Entre todas las obras de Sancho IV, esta descripción solo puede ser aplicada al Lucidario. Después de la venta de la biblioteca en 1964, el manuscrito pasó a la colección de Bartolomé March en Madrid y, tras la muerte de este, fue trasladado, junto al resto de manuscritos, a la Biblioteca de la Fundación Bartolomé March de Palma (sobre este manuscrito, véase Cossío Olavide, “Un nuevo testimonio”).

Resulta interesante resaltar que se trata de un testimonio tardío del Lucidario, de mediados del siglo XVI por su letra y filigranas, mientras que el cuatrocientos acumula seis testimonios de la obra. Hay dos fechados, A (BNE MSS/3369 [BETA manid 1434]) de 1455 y C (Real Bibl. II/793 [BETA manid 1435]) de 1477. D, el códice Puñonrostro (RAE Ms. 15 [BETA manid 1424]), puede ser datado por sus filigranas entre 1450 y 1460 (Cossío Olavide, “D (RAE 15)”). G (RAH Cód. 101 [BETA manid 2285]) es de finales de siglo, mientras que H (Rouen BM A283 [BETA manid 6360]) es de mediados de la centuria.

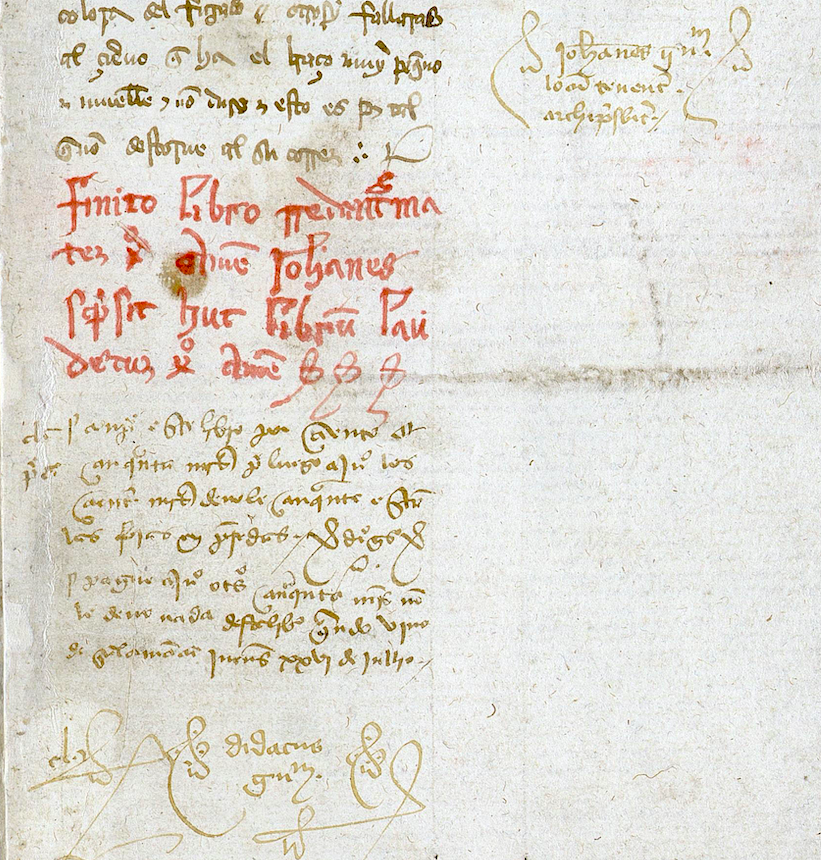

El testimonio B (Salamanca BU Ms. 1958 [BETA manid 1433]) fue durante largo tiempo considerado de este siglo, pero sus filigranas y la letra empleada –muy similar a la cancilleresca– apuntan que fue producido entre 1380 y 1410. Esto es reconfirmado por una nota de compra-venta en los últimos folios, acompañada por las firmas de sus antiguos posesores, dos maestros salmantinos de las primeras décadas del siglo XV. Didacus Gundisalvi, Diego González, catedrático de derecho en la Universidad de Salamanca hacia 1433, y un Johanes Gundisalvi, locum tenentem archipresbiter, que bien podría ser Juan González de Segovia, catedrático de derecho canónico, teólogo y representante de Juan II en el Concilio de Basilea.

Manuscritos hispánicos en colecciones europeas

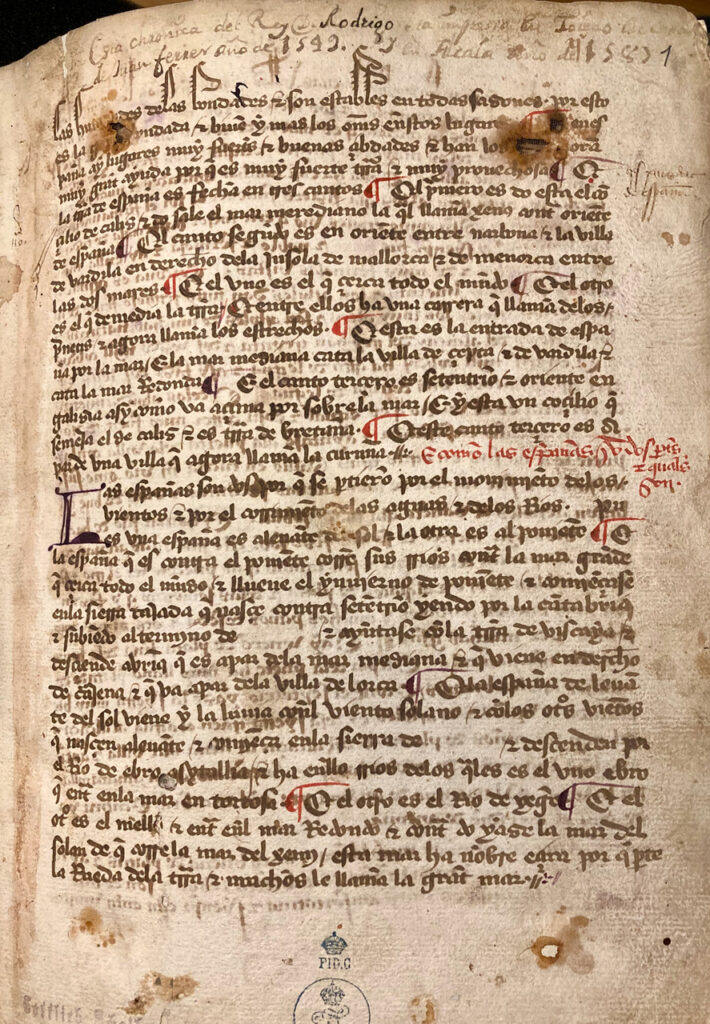

Un manuscrito recientemente redescubierto por Cossío Olavide y Romera Manzanares (“Nuevos testimonios”) es el Series Nova 12736 de la Biblioteca Nacional de Austria (BETA manid 6409), que transmite un testimonio parcial de la mal llamada Crónica del moro Rasis (BETA texid 1400) y de la Crónica sarracina (BETA texid 1462) de Pedro de Corral, datado entre 1460 y 1480.

Además de estos textos, el manuscrito vienés transmite dos romances tempranos en el fol. 36r y la guarda pegada a la contratapa final: Virgilios y ¡Ay de mi Alhama! (o Paséabase el rey moro), según se dará cuenta en Cossío Olavide y Pichel (“Dos romances”).

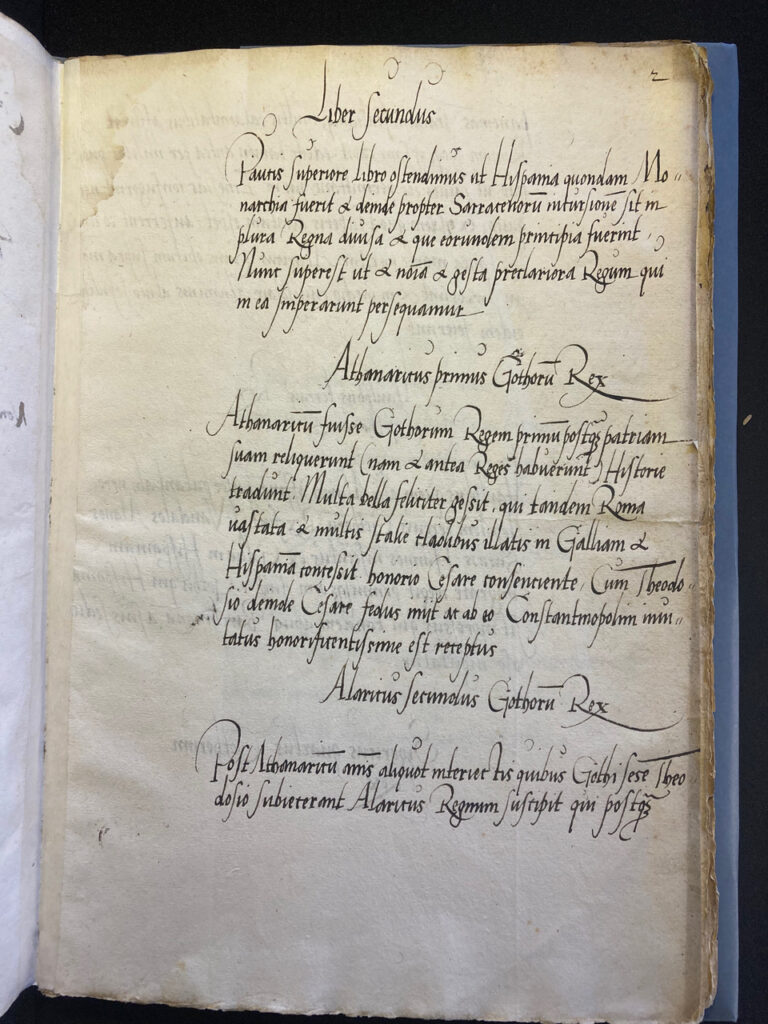

Otro texto de interés es el ms. 9221 de la misma biblioteca, un manuscrito facticio con doble numeración que transmite un repertorio de inscripciones sepulcrales alemanas (fols. 1r-73r) y un breve texto latino de formato analístico sobre los reyes visigodos (fols. 1rbis-10rbis). Aunque se trata de una copia del siglo XIX, parece estar vinculado con el Cronicón de Cardeña.

El manuscrito B702 de la Biblioteca Nacional de Suecia (BETA manid 4469) transmite la versión C del Fuero general de Navarra (BETA texid 1195), ampliado con disposiciones y textos legales añadidos, como el Amelloramiento de Philippe d’Evreux III (BETA texid 3192), estructura compartida por otros testimonios del fuero (BNE MSS/248 [BETA manid 1370] y MSS/ 6705 [BETA manid 3392], Biblioteca Regionale Universitaria di Catania ms. U009 [BETA manid 4600] y Real Biblioteca ms. II/1872 [BETA manid 3242]). Como estos, transmite en los fols. 114r-116v, una interpolación navarro-aragonesa del título de los retos del Fuero Real (libro 4, título 19), incorporada para cubrir un vacío legal en materia de justicia nobiliaria del Fuero general (véase Utrilla Utrilla, “Las interpolaciones” y Fradejas Rueda, “Una decepción”).

Referencias

Cossío Olavide, Mario y Ricardo Pichel. “Dos romances tempranos en un manuscrito historiográfico del siglo XV: ¡Ay de mi Alhama! y Virgilios (con una nota sobre la lectura del Amadís primitivo).” Actas del VIII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Convivio, en prensa.

Cossío Olavide, Mario. “D (RAE 15).” Lucidarios. Editando el Lucidario de Sancho IV. 18/01/2023, https://lucidarios.hypotheses.org/testimonios/d

_____. “Un nuevo manuscrito (Rouen, Bibliothèque municipale Villon ms. A283) y una nueva edición del Lucidario de Sancho IV.” e-Spania, vol. 44, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4000/e-spania.46735

_____. “Un nuevo testimonio del Lucidario: I.” Lucidarios. Editando el Lucidario de Sancho IV. 26/05/2023, https://lucidarios.hypotheses.org/2807

Fradejas Rueda, José Manuel. “Una decepción y un hallazgo. Una nueva copia del Fuero de Navarra.” Las Siete Partidas del Rey Sabio: una aproximación desde la filología digital y material, editado por José Manuel Fradejas Rueda, Enrique Jerez y Ricardo Pichel, Iberoamericana, 2021, pp. 138-43. https://doi.org/10.31819/9783968691503-011

Omont, Henri, editor. Catalogue général de manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques de France. Départaments, t. I. Rouen, Imprimerie nationale, 1886.

Paz y Meliá, Antonio. Series de los más importantes documentos del Archivo y Biblioteca del Excelentísimo Señor Duque de Medinaceli. 2 vols. Imprenta alemana e Imprenta de Blass, 1915-1922.

Romera Manzanares, Ana y Mario Cossío Olavide. “Vieron el escrito y mostráronlo. Nuevos testimonios de la Crónica del moro Rasis y de la Crónica sarracina.” Revista de literatura medieval, vol. 34, 2022, pp. 249-68. https://doi.org/10.37536/RLM.2022.34.1.87619

Utrilla Utrilla, Juan. “Las interporlaciones sobre reptorios en los manuscritos del Fuero general de Navarra.” Prínicpe de Viana. Anejo, no. 2-3, 1986, pp. 765-76.

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 4 (June): The Bancroft Library’s Fernán Núñez Collection

I am delighted to announce that thanks to the efforts of Randy Brandt, Head Cataloguer of The Bancroft Library, it is now possible to find all of the volumes in Bancroft’s Fernán Núñez Collection.

This collection of 224 manuscripts comes from the library of the counts and then dukes of Fernán Núnez, a town near Córdoba, principally from that of the 6th count of Fernán Núñez, Carlos José Gutiérrez de los Ríos y Córdoba (1742-1795), although the nucleus of the collection probably goes back to Juan Fernández de Velasco (1550-1613), 5th duke of Frías and viceroy of Milan. According to the Diccionario Biográfico electrónico of the Real Academia de la Historia, Gutiérrez de los Ríos was a man of broad culture who wrote a biography of King Carlos III and was an honorary member of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid and the Real Academia Sevillana de Buenas Letras.

University of California, Berkeley

Askins, Arthur L-F. “The Cancioneiro da Bancroft Library (previously, the Cancioneiro de um Grande d’Hespanha): a copy, ca. 1600, of the Cancioneiro da Vaticana.” Actas do IV Congresso da Associação Hispânica de Literatura Medieval. Lisboa: Edições Cosmos, 1991: I:43-47 (BITAGAP bibid 2595)

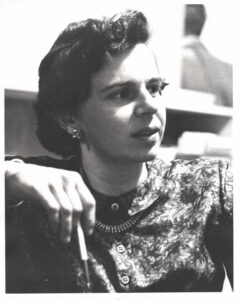

“Doris Sloan: Geologist, Educator, and Environmental Activist,” oral history release

New oral history: Doris Sloan

Video clip from Doris Sloan’s oral history on living in the Bay Area, on deep time, and on thinking like a geologist:

Doris Sloan is a geologist and paleontologist who earned her PhD at UC Berkeley and who taught, wrote, and engaged in environmental activism and education throughout the Bay Area, across California, and beyond. Sloan and I recorded nine hours of her then 92-year life history at her home in Berkeley, California, in May 2022. Our four recording sessions resulted in a 162-page oral history volume that includes an appendix of photographs with family as well as documents from her efforts in the early 1960s to stop PG&E’s construction of a nuclear power plant atop Bodega Head, under which runs the seismic San Andreas fault. Today, the coastal outcrop of Bodega Head is preserved as part of California’s scenic 17-mile-long Sonoma Coast State Park.

to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor (NCAPBHH).

Sloan’s involvement in the “Battle for Bodega Head” helped inspire her later career as a geologist and teacher—a career she began by returning to graduate school as a mother in her early forties with children still at home. Sloan overcame numerous challenges, including gender discrimination in what were then male dominated departments and academic fields, to earn her MS in Geology in 1975 and her PhD in Paleontology in 1981. Her dissertation was an ecostratigraphic thesis on the sedimentary fossils of tiny creatures that once lived the San Francisco Bay. For many years, Sloan taught research-driven senior seminars in Environmental Science at UC Berkeley as well as geology courses for UC Extension. She lectured on travel excursions and field trips around California and across much of the Earth. Sloan became a board member with Save the Bay and a founding member of Citizens for East Shore Parks. In 2006, she published with UC Press the popular California natural history guide, Geology of the San Francisco Region. In her rich oral history, Sloan discussed all of the above, with details on her formative childhood experiences, her environmental and anti-nuclear activism, her experiences as a female geology graduate student at UC Berkeley, as well as her diverse teaching career.

Doris Sloan was born in October 1930, in Freiburg, Germany. At age four, she and her family fled Germany after the Nazis removed her father, preeminent embryologist Viktor Hamburger, from the faculty at the University of Freiburg because of his Jewish ancestry. Her family settled in Missouri after her father secured a faculty appointment at Washington University in St. Louis. As a young girl, Sloan accompanied her father and his embryology students on field research trips to collect salamander eggs. She also shared fond memories of youthful summers working in Woods Hole on Cape Cod at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Sloan attended Bryn Mawr College from 1948 to 1951, where she began attending Quaker meetings. Upon her mother’s deteriorating health, Sloan returned to St. Louis and graduated in 1952 from Washington University with a BA in Sociology. In that same year Sloan moved to San Francisco, California, with her then-husband, with whom she had four children. In 1957, she and her young family moved to Sonoma County, where she was neighbors with Peanuts cartoonist Charles Schulz. It was there in Sonoma County where, in the interests of protecting her children from nuclear radiation and preserving the beauty of the Sonoma Coast, that Sloan began her environmental activism that would, among other experiences, inspire her later career as a geologist and teacher.

Video clip from Doris Sloan’s oral history about her role in the “Battle of Bodega Head, Part 1:

Sloan detailed her engagements in the multi-year “Battle of Bodega Head” that, in 1964, successfully stopped PG&E’s construction of a nuclear power plant on Bodega Head. After being told by an official from California’s Office of Atomic Energy Development and Radiation Protection to let go of concerns about the forthcoming nuclear plant and “leave it to the experts,” Sloan enlisted in the activist organization called the Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor (NCAPBHH)—a name others created and she described as “dreamt up on a Friday night after too many beers.” The Association included an eclectic mix of anti-nuclear citizen activists that included communist chicken farmers, libertarian land owners, conservative cattle ranchers, Bodega fisherman, UC Berkeley professors, Sierra Club members, and jazz musicians and songwriters. In her role as Sonoma County Coordinator of NCAPBHH, Sloan also collaborated with an internationally recognized geophysicist and geologist named Pierre Saint-Amand. Fortuitously, on a rainy and wind-swept day, Sloan accompanied Saint-Amand on a clandestine and consequential visit to the “Hole in the Head,” the site on Bodega Head where PG&E had already drilled a deep pit into granite rock to place its nuclear reactor. It was on that visit, while looking into that hole, that Saint-Amand and Sloan discovered evidence of the San Andreas fault running directly through the reactor’s containment site, a discovery that eventually halted further nuclear construction there.

Video clip from Doris Sloan’s oral history about her role in the “Battle of Bodega Head, Part 2:

As Sloan recalled about their activist victory in the early 1960s, “to have a group of citizens win out over a major institution was really pretty unique. … Bodega was a very important story at the very beginning of a huge cultural shift for not only environmental matters on nuclear energy, but in so many other ways, too. Basically, citizen involvement at every level, from students to housewives. And to be a part of that, I look back on that and think, wow, how could anybody have been so lucky in so many ways?” The story of this citizen-led anti-nuclear activism has been told elsewhere, including in Oral History Center interviews with David Pesonen and Joel Hedgpeth, as well as by nuclear historians J. Samuel Walker and UC Berkeley alumnus Thomas Wellock. Sloan’s storytelling on her personal role in the “Battle of Bodega Head”—like launching over a thousand helium-filled balloons from Bodega Head to the accompaniment of live jazz playing “Blues Over Bodega”—adds both flourish and important details to the eventual successes of NCAPBHH.

Sloan’s involvement at Bodega Head played a crucial role in launching the next phase of her life as a geologist and teacher. After moving with her children to Berkeley in 1963, Sloan worked for the Friends Committee on Legislation, a Quaker lobbying group. Yet, by the early 1970s, Sloan’s long-standing fascination of nature, a desire to experience more of it, and her memory of discovering fault seams on Bodega Head led her to take UC Extension courses on geology taught high up in the Sierra Nevada’s Emigrant Wilderness by a remarkable UC Berkeley professor named Clyde Wahrhaftig. Wahrhaftig eventually became a significant mentor and friend to Sloan on her academic journey, as were UC Berkeley geologists Garniss Curtis and William B.N. (Bill) Berry. In her oral history, Sloan shares many joys from her field research and academic experiences at Berkeley, including mapping rock formations in California’s Mazourka Canyon, communing with ancient bristlecone pines in the White Mountains, learning about limestone deposition in Florida, a fascinating question about an imaginary dinosaur civilization from Walter Alvarez during her PhD oral examination, and her own work deciphering the sedimentary mysteries of fossils from mud under the San Francisco Bay. Sloan also shared some of the challenges she faced in the late 1970s as one of the few women in Berkeley’s geology and paleontology departments that, by her account, then included more than a few male chauvinistic dinosaurs.

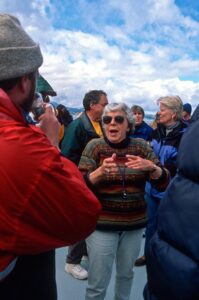

Video clip from Doris Sloan’s oral history about Clyde Wahrhaftig, a UC Berkeley geologist, mentor, and friend:

Sloan’s oral history also explores her ensuing years as a teacher, travel guide, author, and environmental activist. Sloan discussed several senior research seminars in Environmental Studies that she taught at UC Berkeley, some records of which are preserved in UC Berkeley’s Library including East Bay Parklands: Planning and Management (1978), Seismic Safety in Berkeley (1979), San Pablo Bay: An Environmental Perspective (1980), and Hazardous Substances: A Community Perspective (1984). Sloan recorded stories and samples from lectures she delivered in her UC Extension geology courses and in her field classes for numerous organizations, including the Oakland Museum, Sierra Club, the Point Reyes National Seashore Association, and the Yosemite Association. And she shared some of her travel experiences as a guide for Cal Alumni groups on journeys all across the Earth, from the Himalayas to Central Asia, and from South America to Scandinavia. Sloan also spoke about her local environmental activism as a board member of Save The Bay, as a founding member of Citizens for East Shore Parks, and on her friendship with Save The Bay co-founder Sylvia McLaughlin, including efforts to secure what is now named as McLaughlin Eastshore State Park.

Doris Sloan’s enlightening oral history records marvelous stories from the first ninety-two years of her remarkable life—from fleeing Nazi Germany to summers in Woods Hole; from raising children in northern California to stopping construction of a nuclear power plant on the San Andreas fault; from graduate school in her forties at UC Berkeley to lecturing across California and much of the world. I am honored to have become one of Doris’s friends, and I’m lucky for the opportunity to become one of her students. Now, with the publication of Doris Sloan’s oral history, you also have the chance to learn from her deep wisdom and experience.

Video clip from Doris Sloan’s oral history about the Bay Area’s complicated geology:

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 3 (May): NEH support for PhiloBiblon and the Wikiworld

We are delighted to announce that PhiloBiblon has received a two-year implementation grant from the Humanities Collections and Reference Resources program of the National Endowment for the Humanities to complete the mapping of PhiloBiblon from its almost forty-year-old relational database technology to the Wikibase technology that underlies Wikipedia and Wikidata. The project will start on the first of July and, Dios mediante, will finish successfully by the end of June 2025.

The fundamental problem is to map the 422,000+ records of PhiloBiblon’s bibliographies with their complexly interrelated relational tables to the triplestore structure of Wikibase. A triplestore relates two Items by means of a Property. Thus a Work is linked to an Author by the Property “written by.”

We received an NEH Foundations grant for this project in 2021, as described in detail in PhiloBiblon 2021 (n. 3): PhiloBiblon y el mundo wiki: propuesta de una colaboración. Over the course of the last two years, the pilot project team, consisting of Charles Faulhaber (PI), Patricia García Sánchez-Migallón and Almudena Izquierdo Andreu (doctores por la UCM); Berkeley undergraduate Spanish and data science majors (Julieta Soto, Serena Bai, Tina Lin, Cassandra Calciano, Martín García Ángel); Max Ziff (data engineer); and Josep Formentí (user interface programmer), has analyzed the data structures of PhiloBiblon’s ten relational tables (using BETA for the test cases) and worked out the procedures needed to convert them into triplestore structures.

Almudena and Patricia manually mapped more than 125 BETA records to FactGrid: PhiloBiblon as models for the automated processing of the rest. See for example the records for Alfonso X, BNE MSS/10069 (Cantigas de Santa Maria), and the 1497 edition of the translation of Boccacio’s Fiammeta. These models have been key for establishing the semantic relations between PhiloBiblon’s data fields and the Properties and Items in FactGrid. In many cases appropriate properties did not exist and it was necessary to create them. For example, something as simple as the Watermark property was needed in order to identify the various watermark types set forth in PhiloBiblon’s controlled vocabulary.

Julieta Soto and Martín García Ángel attacked the problem of creating almost 900 FactGrid records for the controlled vocabulary terms in BETA. This meant in the first place a search in FactGrid to make sure that an equivalent term did not already exist, in order to avoid creating duplicate records. Then they had to situate the term in the FactGrid ontology by specifying it as a “basic object” (e.g., fruit) or identifying it as a subclass of an appropriate basic object, for example facsímil impreso as a subclass of facsímil. At the same time they had to link the record to the code in PhiloBiblon, BIBLIOGRAPHY*RELATED_BIBCLASS*FAP, identifying a record in the Bibliography table as a print facsimile, thereby making it possible to search for such items.

The default viewer used in FactGrid, the same as that used in Wikidata, is not user friendly. Therefore Josep has created a prototype user interface, using data from the BETA Institutions table. We encourage you to play with it and tell us what you like or—more usefully—don’t like.

This change to Wikibase technology is designed to allow PhiloBiblon not only to take advantage of the linked open data of the semantic web, but also, and most importantly, to decrease sustainability costs. Because Wikibase is open-source software maintained by WikiMedia Deutschland, the software development arm of the Wikimedia Foundation, software maintenance costs for PhiloBiblon will be minimal in the future. This means that it will no longer be necessary to seek major grant support every five to seven years merely to keep up with technology change.

While this work has been going on, we have not neglected the vital process of cleaning up PhiloBiblon data in order to facilitate the automated mapping nor the equally vital process of adding new information to PhiloBiblon. For example, Pedro Pinto, a member of the BITAGAP team, has recently discovered a “folha desmembrada” (BITAGAP manid 7862) from the Livro 4 of the chancery records of king Fernando I (1345-1383) (BITAGAP manid 3255), separated from the manuscript in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo. The newly discovered dismembered leaf contains five previously unknown royal documents. It was being used as the cover of the “Livro de Acordãos, 1620-24,” in the archive of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia in Coruche, a small city in the Santarem district on the Tagus river northeast of Lisbon.

The recycling of parchment leaves from discarded medieval manuscripts, presumably for more socially beneficial purposes, such as the protection of administrative records, was common in both Spain and Portugal in the sixteenth and seventeenh centuries. Such leaves have been the source of many unknown or poorly documented medieval texts. Perhaps the most spectacular example was Harvey Sharrer’s discovery in 1990 of the eponymous Pergaminho Sharrer (BITAGAP manid 1817), with musical notation for seven poems of king Dinis of Portugal (1279-1325). This had been used as the binding of a collection of notarial documents (Lisboa: Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo: Lisboa, Cartório Notarial de. N. 7-A, Caixa 1, Maça 1, livro 3).

Mariña Arbor Aldea

Arthur L-F. Askins

Vicenç Beltran Pepió

Álvaro Bustos Táuler

Antonio Cortijo Ocaña

Charles B. Faulhaber

Patricia García Sánchez-Migallón

Ángel Gómez Moreno

José Luis Gonzalo Sánchez-Molero

Almudena Izquierdo Andreu

Filipe Alves Moreira

María Morrás

Óscar Perea Rodríguez

Ricardo Pichel Gotérrez

Pedro Pinto

Maria de Lurdes Rosa

Nicasio Salvador Miguel

Martha E. Schaffer

Harvey L. Sharrer

Cristina Sobral

Lourdes Soriano Robles

Workshop: HTML/CSS Toolkit for Digital Projects

HTML/CSS Toolkit for Digital Projects

Wednesday, May 3rd, 2:10-3:30pm

Online: Register to receive the Zoom link

Stacy Reardon and Kiyoko Shiosaki

If you’ve tinkered in WordPress, Google Sites, or other web publishing tools, chances are you’ve wanted more control over the placement and appearance of your content. With a little HTML and CSS under your belt, you’ll know how to edit “under the hood” so you can place an image exactly where you want it, customize the formatting of text, or troubleshoot copy & paste issues. By the end of this workshop, interested learners will be well-prepared for a deeper dive into the world of web design. Register here.

Please see bit.ly/dp-berk for details.

Workshop: By Design: Graphics & Images Basics

By Design: Graphics & Images Basics

Thursday, April 6th, 3:10-4:30pm

Location: Doe 223

Lynn Cunningham

In this hands-on workshop, we will learn how to create web graphics for your digital publishing projects and websites. We will cover topics such as: sources for free public domain and Creative Commons images; image resolution for the web; and basic image editing tools in Photoshop. If possible, please bring a laptop with Photoshop installed. (All UCB faculty and students can receive a free Adobe Creative Suite license: https://software.berkeley.edu/adobe) Register here.

Upcoming Workshops in this Series – Spring 2022:

- HTML/CSS Toolkit for Digital Projects

Please see bit.ly/dp-berk for details.

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 2 (marzo). Fuero parece, Real lo es: BH MSS 345 de la Biblioteca Histórica ‟Marqués de Valdecilla”

Mónica Castillo Lluch

Université de Lausanne

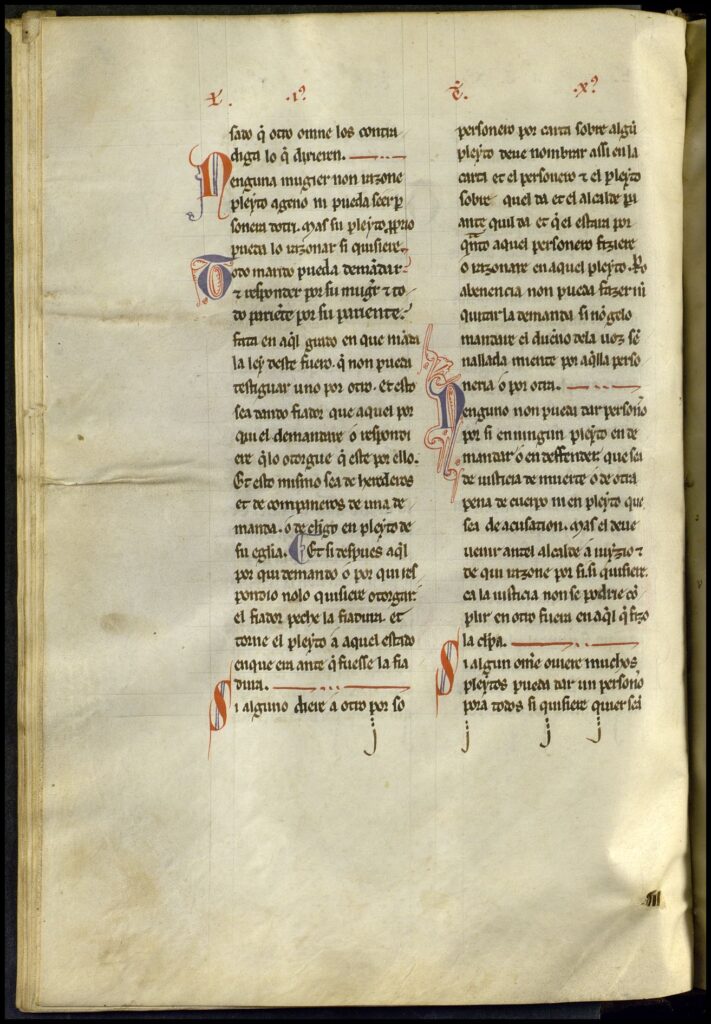

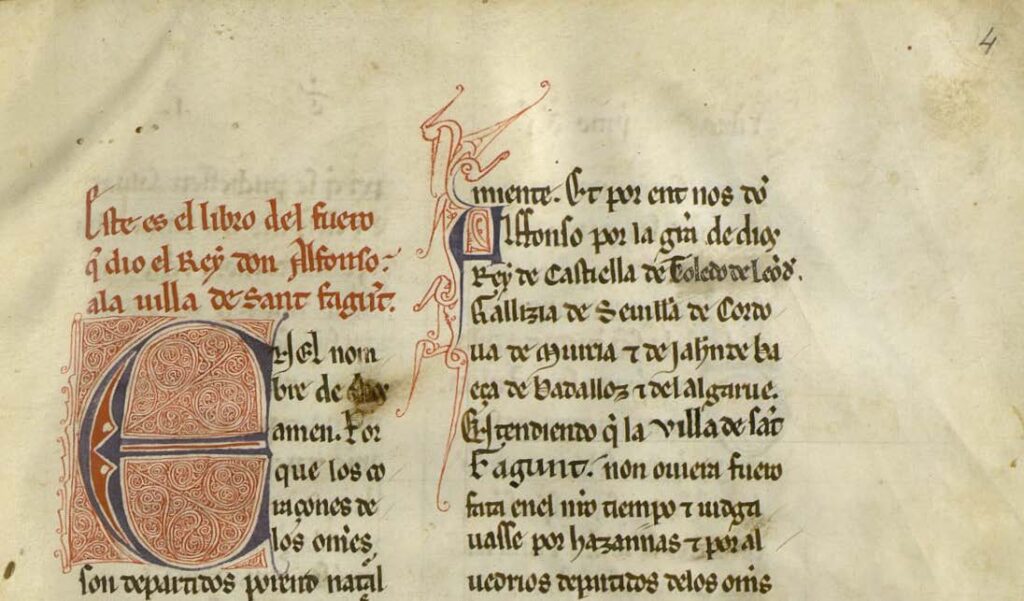

El manuscrito BH MSS 345, custodiado en la Biblioteca Histórica ‟Marqués de Valdecilla” de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, fue catalogado bajo los títulos ‟Libro del fuero que dio el Rey don Alfonso a la uilla de Sant fagunt” y ‟Fuero de Sahagún”, por comenzar su texto de este modo: ‟Este es el libro del fuero que dio el Rey don Alfonso a la villa de Sant Fagunt” (f. 4r, v. imagen 2). Como Fuero de Sahagún se encuentra hasta hoy (18 de marzo de 2023) en el catálogo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid y hasta hace varios días así en PhiloBiblon, bajo BETA texid 2443 con el registro BETA cnum 9301.

Ahora bien, la catalogación de este códice como Fuero de Sahagún es errónea, pues el texto que contiene es el del Fuero Real, como anuncian inequívocamente los índices de sus cuatro libros (ff. 1v-3v) y como revela la lectura del texto. El códice procede del Museo-Laboratorio jurídico ‟Ureña” de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Central (lleva su sello en diversos folios) y por ello sorprende que hasta hoy no haya sido identificado como testimonio del Fuero Real, lo que se comprueba consultando la nómina de manuscritos que ofrecen Martínez Diez en su edición (1988: 22-72) y Fernando Gómez Redondo y José Manuel Lucía Megías en el Diccionario filológico de literatura medieval española (2002: 11-15). Consecuentemente tampoco ha figurado hasta ahora este testimonio entre los que da PhiloBiblon del Fuero Real (BETA texid 1006), error que ya se ha corregido, enlazando el registro con el testimonio en BETA cnum 9301.

Dos razones explican la catalogación defectuosa: de un lado, el título de Fuero Real es moderno –de finales del siglo XV-, y los códices antiguos no lo llevaban; en los pocos códices en los que aparece un título este es el de Libro del fuero, Libro del fuero de las leyes, Libro de las leyes, Libro de Flores o Flores (Martínez Diez 1988: 78-79 y BETA texid 1006). De otro, numerosos códices del Fuero Real se destinaron a localidades concretas (Martínez Diez 1988: 80-91), mediante la fórmula inicial de ‟Libro del fuero que dio el Rey don Alfonso a Burgos, Valladolid, Santo Domingo, Carrión… ”, lo que provoca confusión a la hora de identificar el texto, que se puede interpretar como fuero de esa villa (otro ejemplo del mismo tipo de error es que el códice de Filadelfia del Fuero Real (BETA cnum 3676) aparece como Fuero de Burgos en el CORDE; cf. Rodríguez Molina y Octavio de Toledo y Huerta 2017: 29).

Por desgracia al códice BH MSS 345 le faltan los últimos folios y, por tanto, la data, por lo que nunca sabremos si en la fórmula habitual ‟Este libro fue fecho e acabado en Valladolit por mandado del rey don Alfonso … días andados del mes de… era de 1293” figuraba la fecha de 18 de julio, la de 25 de agosto u otra de ese año 1255. Si nos atenemos al otro ejemplar que se ha conservado del Fuero Real destinado a Sahagún (esc. Z-II-8), que Martínez Diez (1988: 44) fecha de mediados del siglo XIV, y asumiendo que este fuera copia de BH MSS 345 –lo que está por probar–, esa fecha habría sido el 30 de agosto (o el 25, si hubo error de lectura, cf. Martínez Diez 1988: 83). En cualquier caso, merece la pena mencionar que el verdadero Fuero de Sahagún concedido por Alfonso X (BETA texid 2443 en PhiloBiblon) el 25 de abril de 1255, que se conserva en un privilegio rodado original (AHN, Clero Regular-Secular: car. 917, n. 13 BETA cnum 3569), en su dispositivo hace mención de que el rey otorga a la villa el Fuero Real como supletorio: ‟todas las otras cosas que aquí nõ son escriptas, que se judguen todos los de Sant Fagund, cristianos e judíos e moros pora siempre por el otro fuero que les damos en un libro escripto e seellado de nuestro seello de plomo” (texto apud BNE MSS/18128, f. 80v. Cf. Barrero García 1972: 404 y Martínez Diez 1988: 92 y 108).

¿Podría ser BH MSS 345 ese libro del Fuero Real escrito y sellado en 1255? Sin pretender dar una respuesta definitiva a pregunta tan importante en esta nota, cabe aquí al menos apuntar que rasgos textuales, codicológicos, paleográficos y diplomáticos de este códice revelan su antigüedad y hacen verosímil que pueda tratarse de un testimonio salido de la cancillería real en el verano de aquel año.

Desde el punto de vista textual, de confirmarse que BH MSS 345 es el arquetipo de Z-II-8, la calidad del texto de este último (‟ofrece un texto excelente del Fuero Real”, según Martínez Diez (1988: 45), y fue el testimonio elegido por la RAH para su edición de 1836) apuntaría a una fecha temprana de redacción. Entre los aspectos codicológicos y paleográficos que apoyarían la antigüedad del testimonio, podrían señalarse el intercolumnio partido para destacar las capitales, estas mismas capitales destacadas, las ocurrencias de d semiuncial interior ante vocal de trazo curvo o de r de martillo en los grupos br, pr (cf. Rodríguez Díaz, próxima publicación).

Pero hay otro elemento codicológico que nos interesa subrayar por su posible asociación más precisa con 1255. Sahagún era por aquel tiempo una villa de la merindad mayor de Castilla (Martínez Diez 1988: 110), como otras a las que posiblemente se les concedió de modo general el Fuero Real en la primavera de 1255 (Iglesia Ferreirós 1971: 950 y Craddock 1981: 384-385). Esto explicaría la intensísima actividad de la cancillería en el verano que siguió, durante el que se multiplicarían en ella los ejemplares del Fuero Real. Como ya se ha indicado, gran parte de esos libros iban destinados nominalmente a las villas (Martínez Diez 1988: 80), y para facilitar la producción en masa de estos se recurrió al método del formulario: se dejaba en blanco el espacio del nombre de la villa, que se rellenaría después. Esto explicaría que en ese punto del texto varios de los códices que se han conservado presenten el nombre sobre un raspado (Burgos en Z-III-13, siguiendo a Craddock 1981: 385) o anacolutos (Z-III-17, ibidem), así como quizá la gran variabilidad de las fórmulas genéricas (Martínez Diez 1988: 81). Pues bien, en el caso de BH MSS 345, su diseño se corresponde a todas luces con el de un formulario: se dejó ese hueco rellenado después con una letra de módulo superior a la del resto del texto, de diferente factura y con tinta de tono más oscuro. En cuanto a la rúbrica, ha de pensarse en una intervención posterior a la inserción del nombre de la villa destinataria, pues en ella no se aprecia el mismo fenómeno.

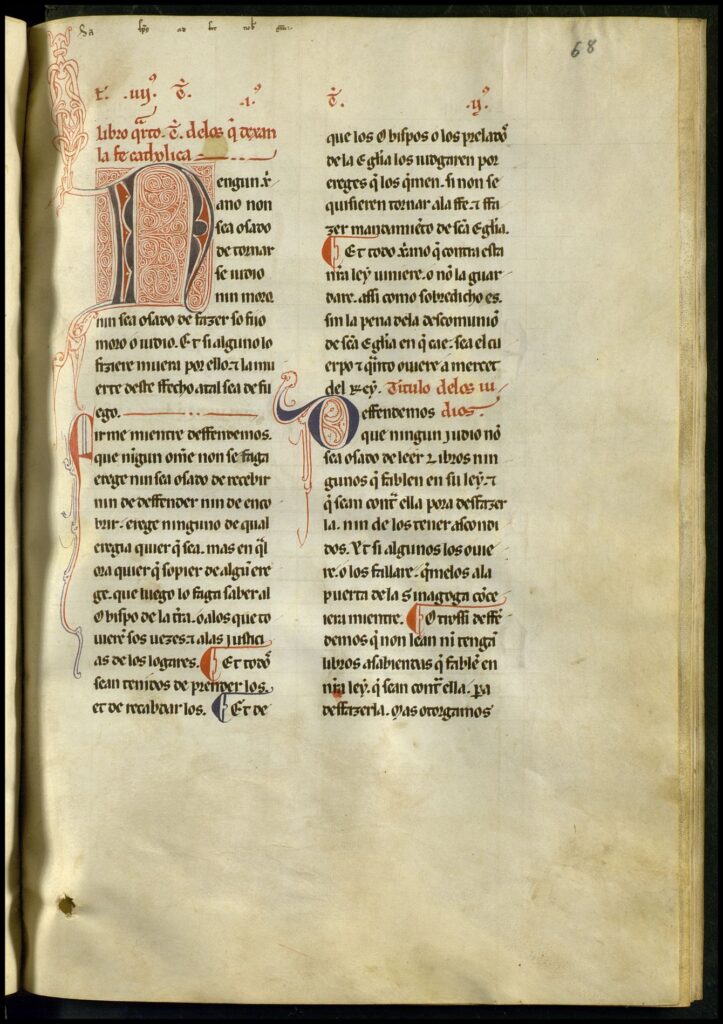

Confirma el carácter de formulario el hecho de que en la ley de las iglesias juraderas (2.12.3, f. 33r), se dejaron 7 líneas en blanco (12-18a) para que se rellenaran después con precisión de la iglesia en cuestión en función de la villa a la que se destinaba (Martínez Diez 1988: 86-87). Parece ser la misma mano del f. 4r la que rellena esas líneas y lo hace con la mención de la iglesia de Santiago, una de las principales de Sahagún en aquel momento (cf. imagen 3).

Por último, cabe señalar que el pergamino de todo el códice está taladrado en su vértice inferior izquierdo para pasar los hilos de seda de los que colgaría el sello de plomo que lo validaría como emitido en la cancillería real (cf. imágenes 3 y 4). Este parece ser uno de los métodos habituales de aposición de sellos en los cuadernos y libros alfonsíes (Ruiz Asencio 1988: 153).

En definitiva, estimo que este testimonio del Fuero Real que viene ahora a sumarse a la lista de los que ya se conocían podría haber sido producido en 1255 a partir del original de la cancillería real. Corresponde ahora examinarlo en detalle desde un punto de vista estructural, paleográfico, codicológico y lingüístico para poder confirmar esta primera impresión. El trabajo en curso de Inés Fernández-Ordóñez y Elena Rodríguez Díaz (2021) sobre el manuscrito BNE MSS/7798 (BETA manid 3086), también recientemente identificado como un nuevo manuscrito antiguo del Fuero Real, podrá tener en cuenta BH MSS 345, evaluarlo a la luz del resto de la tradición manuscrita y valorar si se produjo, junto a otros de los testimonios conservados, como original múltiple. Entre estos podrían igualmente encontrarse los membra disiecta de un manuscrito custodiado en el Archivo de la Real Cancillería de Valladolid (BETA manid 5754) al que en este mismo blog dedicó Jerry Craddock un post en 2016 (The original manuscript of the Fuero real (Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería?).

Otra buena noticia es que la Biblioteca Histórica ‟Marqués de Valdecilla” está redactando actualmente un adendum a su catálogo y que rectificará el registro de este códice en breve, lo que ya ha sucedido en PhiloBiblon.

P.D. Precisamente a base de esta noticia de la profesora Castillo Lluch hemos podido rectificar los registros de PhiloBiblon, quitando el enlace de BETA cnum 9301 con el registro del Fuero de Sahagún (BETA texid 2443) para enlazar este testimonio correctamente con el registro del Fuero real (BETA texid 1006). [Charles Faulhaber]

Bibliografía

Barrero García, Ana María (1972), ‟Los fueros de Sahagún”, AHDE 42, 385-597.

Craddock, Jerry (1981), ‟La cronología de las obras legislativas de Alfonso X el Sabio”, AHDE 51, 365-418.

Fernández-Ordóñez, Inés y Rodríguez Díaz, Elena (2021), ‟Un manuscrito del siglo XIII del Fuero real”, comunicación presentada en “Alfonso X y el poder de la literatura (1221-2021)”. Congreso internacional, Iemyrhd, Universidad de Salamanca, 2021 (22-24 de noviembre).

Gómez Redondo, Fernando y Lucía Megías, José Manuel (2002), ‟Fuero Real”, en Alvar, Carlos y Lucía Megías, José Manuel, Diccionario filológico de literatura medieval española: textos y transmisión, Madrid, Castalia, 11-15.

Iglesia Ferreirós, Aquilino (1971), ‟Las Cortes de Zamora de 1274 y los casos de corte”, AHDE 41, 945-72.

Martínez Diez, Gonzalo (1988), Leyes de Alfonso X. II. Fuero Real (edición y análisis crítico), Ávila, Fundación Sánchez Albornoz.

Rodríguez Díaz, Elena (próxima publicación), ‟Elementos para fechar los códices leoneses y castellanos según los manuscritos datados (ss. XII y XIII)”, en Ángeles Romero Cambrón (ed.), La ley de los godos. Estudios selectos, Peter Lang.

Rodríguez Molina, Javier y Octavio de Toledo y Huerta, Álvaro (2017), ‟La imprescindible distinción entre texto y testimonio: el CORDE y los criterios de fiabilidad lingüística”, Scriptum digital. Revista de corpus diacrònics i edició digital en Llengües iberoromàniques 6, 5-68.

Ruiz Asencio, José Manuel (1988), ‟Estudio paleográfico”, en Gonzalo Martínez Diez, Leyes de Alfonso X. II. Fuero Real, Ávila, Fundación Sánchez Albornoz, 133-59.

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 1 (fevereiro). Escrita de história, memória e gestão de um grupo familiar da nobreza portuguesa, séc. XV-XVI: descoberta, recuperação e estudo de manuscritos inéditos

Mª de Lurdes Rosa, Margarida Leme, Fábio Duarte e Miguel Ayres de Campos

Instituto de Estudos Medievais

Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas

VINCULUM ERC project

É com gosto e entusiasmo que partilhamos a descoberta de uma crónica nobiliárquica quinhentista, há muito perdida, e de dois inventários de arquivo de família com ela relacionados, e igualmente apenas há poucos anos recuperados – sendo o seu estudo integrado um trabalho inédito em curso.

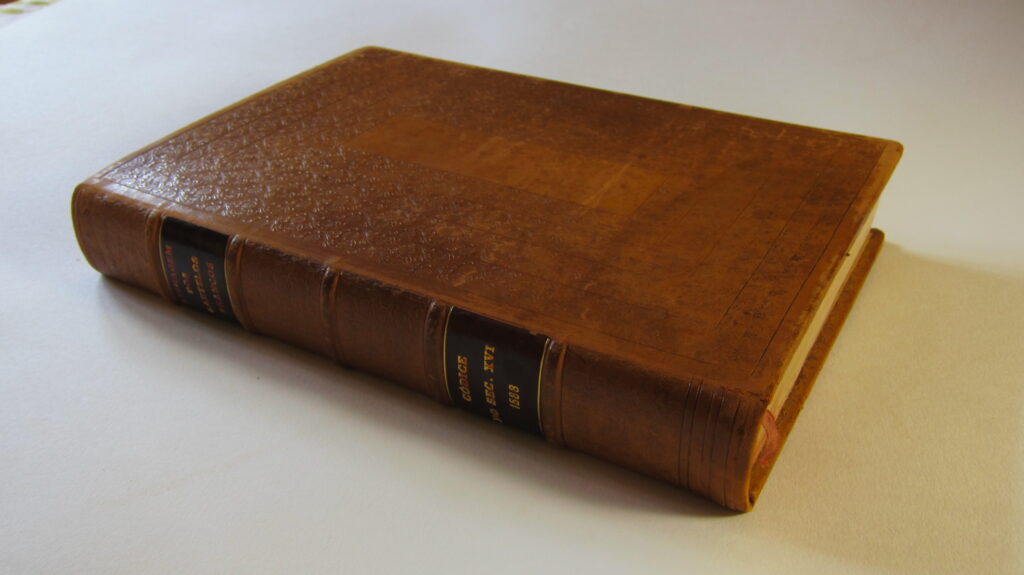

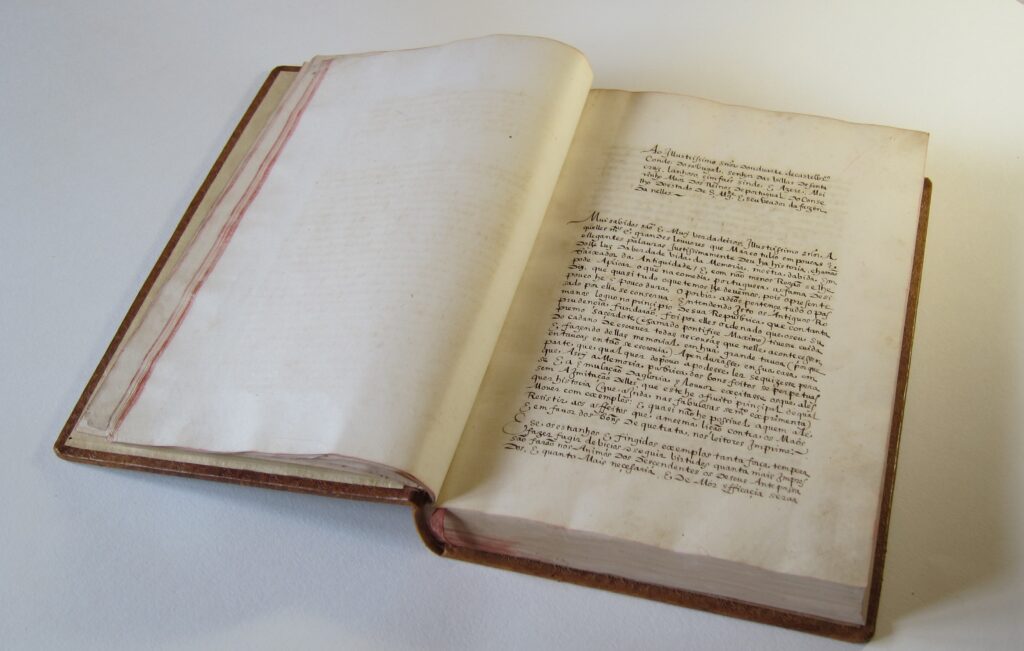

Descobertas

O manuscrito da crónica nobiliárquica quinhentista, conhecido como Descendência e linhagem dos Castelo-Branco (doravante Crónica), está datado de 1588 e contém um longo texto de 261 fólios, em escrita elegante e cuidada. Em cento e dezasseis capítulos narra a história e a genealogia de um grupo familiar da nobreza portuguesa, os Castelo-Branco, estando dedicada a um dos seus expoentes ilustres na época, Duarte Castelo-Branco, conde do Sabugal, meirinho-mor e vedor da Fazenda. Encontra-se nas mãos de um colecionador privado, Doutor Miguel Ayres de Campos, que a cedeu de forma generosa ao projeto VINCULUM para ser estudada e editada.

Este projeto, financiado pelo European Research Council, tem com o objetivo o estudo do funcionamento das instituições de morgados e capelas (vinculação), em Portugal e seus territórios atlânticos, em perspetiva comparada com outros reinos do sul da Europa[i]. A forma como os grupos sociais que recorriam ao estabelecimento de vínculos para reforço da sua riqueza identitária e simbólica é uma das áreas de estudo de projeto VINCULUM, na qual materiais como as narrativas genealógicas e familiares tem grande relevo. Por acréscimo, o grupo familiar dos Castelo-Branco, que se organiza em diversos núcleos fortes, ricos e influentes na Corte portuguesa desde inícios do século XV, permite um dos mais interessantes estudos de caso do projeto.

Uma característica comum aos vários núcleos, entre os quais o dos Conde do Sabugal, foi a atenção aos arquivos e às práticas de gestão de informação das casas e das propriedades; uma outra, o cultivo das belas-letras e de vários tipos de saberes técnico – científicos. A literacia jurídica e contabilística permitiu-lhe aceder por gerações a cargos cimeiros da corte, ligados ao direito e à gestão do reino e dos bens régios, desde a Casa do Cível à vedoria da fazenda, passando pelo meirinhato-mor. A influência política dos Castelo-Branco permitiu que assumissem posições de relevo também no interior dos conselhos e juntas que auxiliaram monarcas portugueses e espanhóis. Entre os vários ramos, avultam senhores que cultivavam saberes como a astronomia, matemática e genealogia. A título de exemplo, tenha-se em consideração que Martinho, primeiro conde de Vila Nova de Portimão, foi íntimo do humanista italiano, residente em Lisboa, Cataldo Sículo; que no espólio fúnebre de um dos seus netos, morto em Alcácer Quibir, se encontrava “um livro de Luis de Camões” e um outro de Ludovico Ariosto; e que Manuel de Castelo-Branco, segundo conde de Vila Nova, foi autor de um livro com árvores genealógicas da aristocracia portuguesa, impresso em 1625, e de uma relação manuscrita acerca da história da sua linhagem.

A Crónica de que agora se trata espelha bem a riqueza de informação circulante no grupo, quanto ao seu passado e ao seu presente. São inúmeros os documentos e os livros citados, pelo que se vê de uma primeira análise. O conhecimento dos arquivos da família era especialmente prezado, e o estudo da Crónica será enriquecido com o de dois outros manuscritos, descobertos no âmbito de um dos projetos antecessores do VINCULUM, o projeto INVENTARQ[ii].

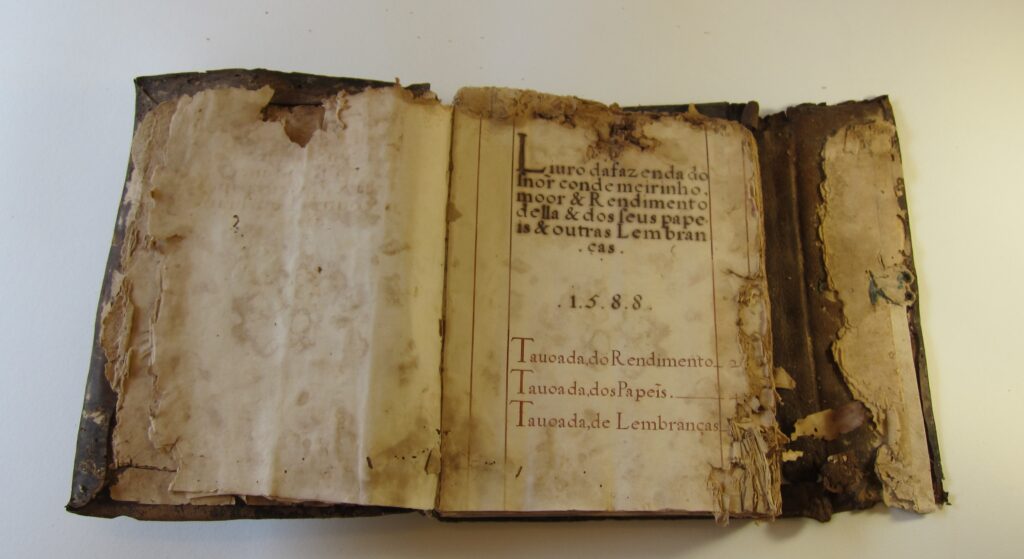

Também em mãos privadas, e generosamente disponibilizado para estudo, em 2015, ao grupo ARQFAM[iii] e, agora, ao projeto VINCULUM, é o Livro da Fazenda do Senhor Conde Meirinho-Mor e rendimento dela e dos seus papeis e outras lembranças. Códice in 4º, de 293 páginas numeradas, encadernado em pele, datado também de 1588, fez parte do Arquivo da Casa de Óbidos onde terá entrado pelo casamento da condessa de Sabugal e Palma com o 2º conde de Óbidos, em 1669. No arquivo da Casa terá permanecido mesmo depois de ter sido entregue, já no século XX, ao marquês de Santa Iria herdeiro dos condes de Óbidos. Está agora nas mãos de um colecionador privado, Arquiteto Jorge Brito e Abreu. Apresenta com a Crónica muitas semelhanças materiais, desde logo o tipo de letra; o seu restauro total, a finalizar em 2023, permitirá a leitura de páginas muito danificadas, e uma analise cuidada.

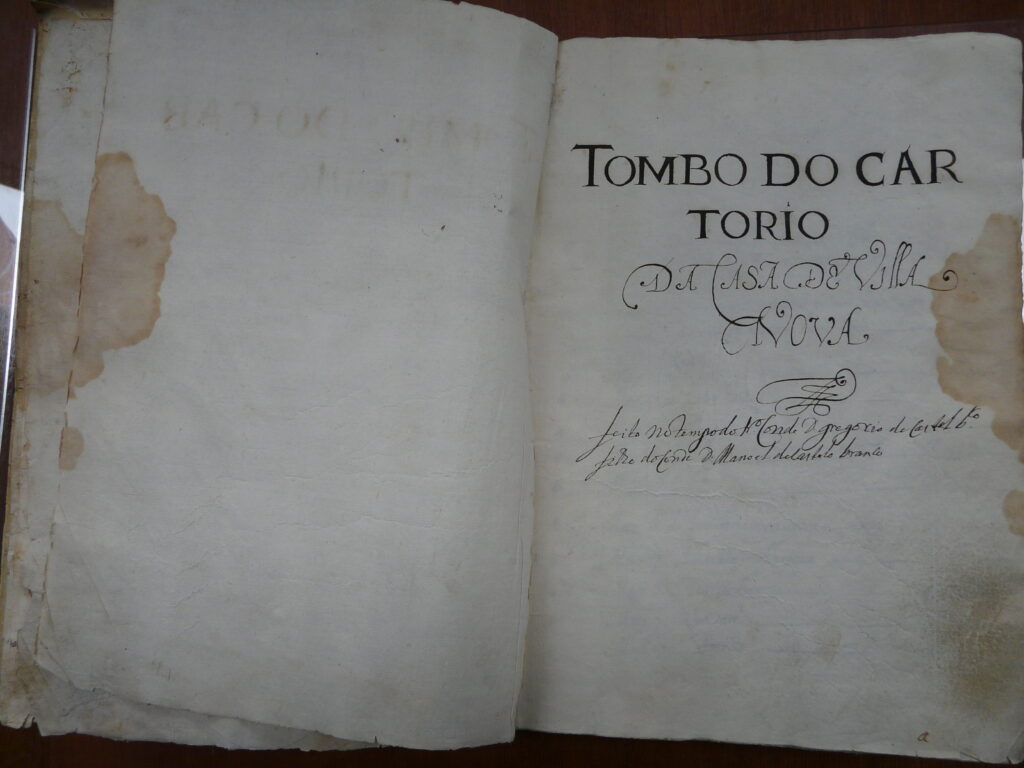

Já o Tombo do Cartório da Casa de Vila Nova de Portimão, atualmente à guarda do Centro de Documentação do Museu Municipal de Portimão, após compra no mercado livreiro, é proveniente da dispersão do arquivo da Casa de Abrantes pelos proprietários, ao longo da segunda metade do século XX. Ao que tudo indica, foi mandado fazer pelo segundo Conde de Vila Nova de Portimão, com sua direta intervenção; a redação final datará dos primeiros anos do século XVII, mas a empreitada deve ter começado nas últimas décadas da centúria anterior – o que o coloca em provável contemporaneidade com os dois documentos Sabugal. Foi editado e estudado por um dos atuais membros da equipa do projeto, Fábio Duarte, na sua tese de mestrado[iv], no âmbito de programa ARFAM, a decorrer na Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da U. Nova de Lisboa desde 2010 e da área de formação em Arquivística Histórica da mesma instituição.

Embora não se saiba, igualmente, quem foi o responsável pela elaboração do Tombo do Cartório, note-se que esta, como as outras iniciativas já referidas, foi acompanhada de perto pelos membros da família Castelo-Branco e levada a cabo num breve intervalo de tempo. Não deixa de ser curioso apontar que, concomitantemente, em 1609, Gaspar Coelho Aranha, prior da vila da Atalaia, terminava a mando do terceiro conde de Sortelha, D. Luís da Silveira, genro do segundo conde de Vila Nova, a composição da Tabuada do cartório da Casa de Sortelha[v]. Aqui, uma vez mais, a reorganização de um arquivo familiar surgia a par da veiculação de uma ideia de memória nobiliárquica e da defesa do património conservado e transmitido durante gerações. O cura arquivista faz uma sugestão que poderá parecer estranha, ou megalómana, mas que afinal reflete a extrema importância conferida aos documentos familiares: o Conde deveria estabelece em Góis, vila principal entre as suas propriedades, um arquivo que albergasse os seus preciosos originais. Este arquivo chamar-se-ia, nem mais nem menos, do que «Torre do Tombo de Goez», e o cura relembra que o segundo conde, avô do atual, mandara fazer uma coleção de grande “tombos” semelhantes aos dos reis, onde registaram os seus bens e direitos. Num contexto alargado, estas composições e reorganizações de arquivos – que, como veremos, irão servir a Crónica – testemunham claramente de uma prática de escrita de gestão e de história-memória-genealogia dos Castelo-Branco e famílias afins, na qual avultam alguns longuíssimos testamentos que são, na verdade, “tratados de domesticidade”, contendo instruções aos sucessores sobre gestão política, económica, religiosa e afetiva das Casas e dos homens e mulheres por elas abarcados.[vi]

Autorias

Se para os dois inventários de Arquivo, as autorias – que se colocam, de resto, de modo diverso do que para um texto literário – estão parcialmente esclarecidas, quanto à Crónica tal não sucede ainda. No momento atual, colocamos mesmo a hipótese de 1588 ser a data não da redação, mas sim de uma cópia, feita para Duarte de Castelo-Branco, mesmo se o texto está dedicado àquele titular. O Prólogo pede vénia de erros de copista que não sabia ler latim, pelo que foi escrito após um exame da cópia, que teve aliás outros acrescentos e retificações expressamente referidos no Prólogo. Este terá sido por copiado após finalizado, incluindo a advertência quanto aos erros, pelo mesmo calígrafo do resto, e colocado no caderno inicial do livro.

Outros indícios apontam para escritas em diversos momentos, ou incorporações de outros textos. No capítulo 57 escreve-se “…foraõ aas mujtas moradas de casas da famosa rua Nova de Lisboa que ora são do meirinho moor dom Duarte de Castelbranco e lhe rendem mais de hum conto de reis”. A menção a Duarte Castelo-Branco é algo indireta, não se parecendo com outras que lhe são feitas como promotor da Crónica; sobretudo, não é referido como chamam “Conde”, título que já detinha em 1588.