Russia has dominated popular discussion recently, as news junkies and casual observers alike can tell you.

But how much do you actually know about the country’s history?

As it turns out, 2017, which has been anything but uneventful so far, marks 100 years since the Russian Revolution. And although the Kremlin may not be officially commemorating the centenary, the UC Berkeley Library is exploring the topic in a vivid new exhibit at Moffitt Library.

For those who need a refresher, the revolution consisted of a pair of coups, both in 1917: The first saw the demise of the monarchical government of Tsar Nicholas II, and the other, led by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks, led to the rise of the world’s first communist state, which would fall in 1991 (which, for some millennials, might as well be ancient history).

With feedback from key scholars on campus, Liladhar Pendse, Slavic and East European studies librarian at UC Berkeley, curated the exhibit, called “The Russian Revolution Centenary: 1917-2017: Politics, Propaganda and People’s Art.”

“The revolutions result in upheavals that generally lead to big transformations and social changes,” Pendse said. “How do those who have come to power behave? What kind of social and economic changes do they implement in the name of ‘humanity’? How do artists and authors behave and create new ‘transformative’ genres?”

The exhibit explores these questions through three major themes: politics, propaganda and the people’s art.

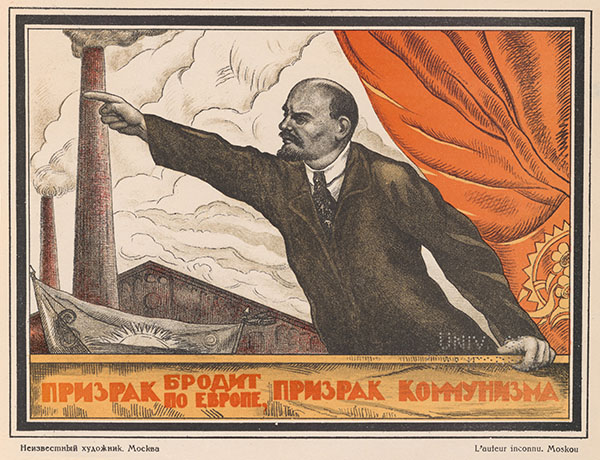

Because of the widespread illiteracy in the Russian Empire at the time, imagery became a potent force in conveying ideas. The result is an exhibit that is “highly visual.”

Revolutionary posters served as tools of propaganda for the early Soviet government. (You’re probably familiar with the aesthetic, which has served as an inspiration for everything from album covers to candy ads.) The Communists tried to replace familiar religious iconography with images of warriors or workers, symbols that were used to evoke the “just society” they envisioned. And the public art that was created by — and for — the people reinforced the expected norms of equality in the “new world,” Pendse said.

Pendse hopes the exhibit will help students learn about other viewpoints, encourage them “to think outside of the box” and remember the past, he said.

“At the back of my mind is what we can learn from history,” he said.

The exhibit is on view through Jan. 8. See the exhibit on the third floor of Moffitt Library — you’ll need a Cal 1 Card for entry. Click here to see the exhibit’s virtual counterpart.